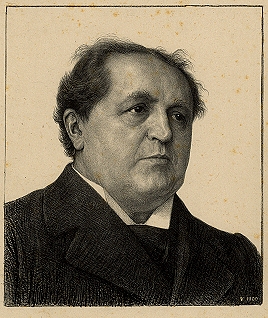

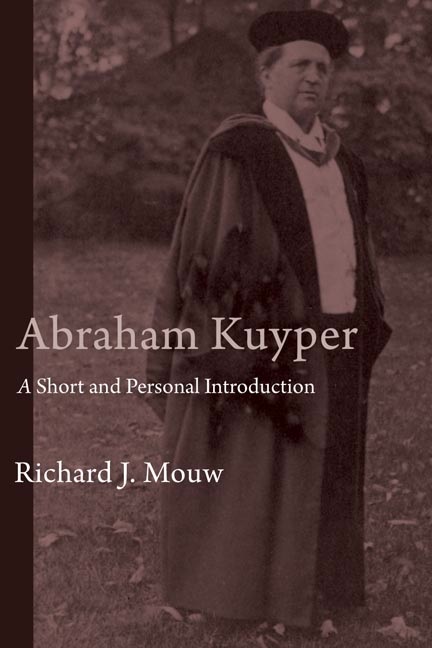

I know what some of you are thinking. He’s on the kick about Abraham Kuyper, again, saying we should serve God in all of life and how the CCO does campus ministry out of that broad, evangelical vision, and that local churches should be more intentional about nurturing in congregants practices about public discipleship, relating faith and work and civic life. If we want to change the world in appropriate ways we should read widely and think faithfully. He’s going to go on and on and on, like he did with the Rob Bell Love Wins reviews. Is this review of this little book, Abraham Kuyper: A Short and Personal Introduction (Eerdmans; $16.00) going to take me a day or more to read?

Well, yes, this is a large part of the Hearts & Minds story, and discovering the way the 19th century revival in Holland led to cultural renewal and social restoration–the very architecture of society was transformed for greater human flourishing and justice for all–was not only eye-opening for me, but set us on a direction which has shaped the texture of our bookstore work. We know this isn’t for everyone, but we have reason to think our readers care. I hope we’re a little bit right.

Richard Mouw, a self-avowed Kuyperian (or neo-Calvinist as some put it, to capture the  reformational tone of the tradition and not only the teachings of the man) has done a short and personal overview of this great Dutch thinker, devotional writer, pastor, scholar, politician, and social reformer. As we explained in the previous post, it seemed to be an opportunity for us to tell our story, or at least part of it, showing how Kuyperian themes have influenced our passion to sell books of the sort we do. We want to invite those who don’t know much about Prime Minister Kuyper to treat themselves to a few hours of quick learning about him by picking up Richard Mouw’s little book. Come on along, it will be good for you. You’ll learn a bit in this review, I hope, and I certainly hope that you find it interesting enough to order the book. You can see our discounted sale price below.

reformational tone of the tradition and not only the teachings of the man) has done a short and personal overview of this great Dutch thinker, devotional writer, pastor, scholar, politician, and social reformer. As we explained in the previous post, it seemed to be an opportunity for us to tell our story, or at least part of it, showing how Kuyperian themes have influenced our passion to sell books of the sort we do. We want to invite those who don’t know much about Prime Minister Kuyper to treat themselves to a few hours of quick learning about him by picking up Richard Mouw’s little book. Come on along, it will be good for you. You’ll learn a bit in this review, I hope, and I certainly hope that you find it interesting enough to order the book. You can see our discounted sale price below.

We all should know something about the great heroes of the faith, of course, and we have a wide batch of biographies and compilations from church history here at the shop. We should learn from Saint Francis and William Wilberforce, read from Bonaventure to Bonhoeffer, study Julia of Norwich, Jonathan Edwards, Karl Barth and more. We should read Blaise Pascal to, well, to Abraham Kuyper. And Kuyper (because of his remarkable achievements, his deep balance of both piety and political action, and his extensive body of writing) is well, well worth knowing about. So, yep, in the last post I used the new Mouw book about him as an excuse to tell our story, why learning about him helped us broaden our vision and deepen our principles. We want to invite folks to pay attention to old Abe. I believe his work is more important than many realize.

After the overview in the last post it remains for me now to tell a bit of what Dr. Mouw covers in this delightful, accessible introduction. I noted that the subtitle indicates that it is personal, and it is. Mouw is excellent at the shorter form and these chapters could stand alone in some cases, they are that clear and concise, each with a lovely illustrative story or clarifying analogy. He tells stories of his own life, inspired by his reflecting and teaching this material for most of a lifetime. Mouw is a good speaker and teacher and this intro walks us through what are, in some cases, some serious thickets, marking a path for us to understand and ponder Kuyper’s philosophy, its strengths and weaknesses and its usefulness for us today.

DYKES AND DAMS IN THE DUTCH MIND

Mouw doesn’t overstate this fascinating bit of speculation, but he does have a few pages on what some have considered to be a unique and long-standing characteristic of the Dutch. Scholars have noted that they love to make distinctions, to clarify and sort, to mark boundaries. There are intellectual habits among this culture that “like to see things clearly.” Dr. Mouw quotes one scholar who notes that this could come from the many “dykes and dams” in Holland—“both as to our land and our mental life” as that writer put it. A Scottish pastor who worked in Holland wrote that perhaps this is “wrought into their nature by many centuries of un-relaxing toil in making and holding that distinction between land and sea, which to them is a matter of life and death.”

MANY-NESS IN CREATION

If there is a proclivity to make distinctions in the Netherlands, it may have rubbed off on Kuyper, and it is seen in key portions of his work which are, in fact, about what he insists are God-given boundaries. It may be seen, too, in how so many of us neo-Calvinists continue to draw vast implications from the stories of God creating things “after their own kind” in Genesis.

It is essential if one is to understand Kuyper’s theology of culture to realize that it is about boundary-markers and honoring God’s intentions for various spheres to develop without undue influence from others. To put it bluntly, Kuyper has this sense that the created order works as it ought when no one big institution (most obviously, the government, but one might consider big business or the mass media, or in medieval Europe, the Catholic church) overly controls or influences us and our daily living. Families, schools, art guilds, local businesses, sport teams, churches, social service clubs, and other voluntary associations should be encouraged to flourish unencumbered by other spheres.

Gordon Spykman was a Dutch-immigrant theologian and philosopher (the Kuyperian tradition values philosophy as well as theology, so there are a lot of vital philosophers who are distinctively neo-Calvinist—let Max Weber try to explain that!) My friend (philosopher) Pete Steen introduced us to him back in the 70s and in one scholarly journal, Spykman wrote,

Each sphere has its own identity, its own unique task, its own God-given prerogatives. On each God has conferred its own peculiar right of existence and reason for existence.

The implications of this are vast, and in this book, Mouw explores some of them. Obviously this means that the church or state ought not try to run anything other than, well, the church or the state. (The state is a particular influential institution, though, as it does have a regulatory task, authorized by God to be somewhat involved in every sphere—think how the government must remove a child from an abusive home or should regulate the food industry or may do intrusive audits of businesses that are financially deceptive. It isn’t a violation of the task of the state when they tell you what side of the road to drive on, after all, and your pastor or employer isn’t authorized to declare that.) So Kuyper is for institutional diversity and this tends towards a localism, it seems to me, inviting many social networks and institutions to develop freely.

By the way, just as an indication of Kuyper’s desire to be clear that the authority of the church shouldn’t impose on the public square, when he ran for elected office he renounced his ordination. His authority as magistrate shouldn’t be confused with that of a pastor. Something, huh?

WORKERS and CALLINGS

Another implication (the focus of a few later chapters of the Mouw book, in fact) might be that if God has built into the creation the possibility of these various spheres to be developed—creativi

ty and the arts, journalism and mass media, family life, business, science, education, politics, entertainment, governments local and national—then those who are are called into them are themselves “prophets, priests and kings” in those fields. That is, there is no sacred-secular dualism that values, say, church life or theological theory over, say, business life and economic theory. If God has ordained various spheres then surely God has called various people to serve in those spheres. All who follow the Christ, then, are of equal value to God’s reign and work in the world, not just missionaries or ministers. (Speaking of which, why do some churches offer scholarships for some of their young people if they go to seminary, but not if they, say, go into engineering? Kuyper might roll over in his grave, and he was himself a theologian and pastor!)

If Kuyper is right that all spheres have their own God-given limits and purposes, then it follows that each person in leadership in those fields are to obey and serve God in those fields, being a steward of the gifts and possibilities in that field. This is the full blossoming of the “priesthood of all believers” for which the Protestant reformation was known. With a Kuyperian emphasis on the spheres and their unique character and calling, there is a liberation of the laity to serve God in public life in normative ways, not only in the local congregation.

(Can you see why a somewhat Kuyperian bookseller like myself thinks that Christian people need good books about their various careers and spheres? Of course we “focus on the family” here but also the marketplace, the job site, the university, the doctors office, the boardroom, the bedroom. We have books on everything because God created everything and sends us into every zone of life to glorify God by serving our neighbors there. It is no wonder that Kuyper founded a university to work out the scholarship to equip people to serve like this. It is the least we could do to start a bookstore!)

IDOLS

Another implication that Mouw studies early in Abraham Kuyper… is that this opened up, multi-faceted view of the God-created nature of social spheres gives us a large and useful tool to discern idolatry. Idols are often corporate and cultural and lead to overblown spheres, squeezing out other sides of life. For instance, statism is just one example, where, as in socialism, the state is given (or takes) too much authority to do too much. Freudianism was an ideology that overstated the role of dysfunctional sexuality; Darwinism perhaps overstates the biological. Technicism makes an idol out of the good gift of technology, and scientism reduces everything to that sphere. Mouw’s helpful chapter “When Spheres Shrink” shows Kuyper’s prescient insight about the modern condition, and he says it better than I do here.

(By the way, C.S. Lewis had a similar take on this and I believe coined the phrase “nothing buttery” to mock those who say life is “nothing but…” this or that. You know, love is nothing but hormones, a feeling for God is nothing but brain chemistry, ethics are nothing but social conventions. Each takes a legitimate insight about how a sphere of life works—hormones, neurons, social conventions) and says that is all there is. Reductionism as idolatry. Kuyper’s books maybe taught it to him, who knows? Lewis read quite widely, you know.)

I hope you understand how I’m using this rhetorical device, adding “ism” to a word in order to illustrate how we turn a legitimate thing in God’s good world that functions properly into an ideology that damages us and deforms our society. Again, for instance, militarism is condemned repeated in the Bible as it turns military might into something to be trusted; an ideology of idolatry. Economism is that tendency where in consumer capitalism, economic growth is seen as the engine by which everything runs and things that ought not be reduced to their financial side are seen that way. I once heard Os Guinness talk about how he knew a person who literally told a friend how much she could have made if she were working while she was having a glass of wine with her friend, putting a “price” on the hour of fellowship. The best treatment of this, succinct and powerful, can be found in chapter 9 of The Transforming Vision: Developing a Christian Worldview by Brian Walsh & RIchard Middleton (IVP; $16.00.) I am pretty sure they get this worldviewish cultural criticism from the legacy of thinkers in the tradition of Kuyper and his social philosophy. I think it is important for anyone who wants to be cultural wise and discerning in our confusing modern times.

I hope you understand how I’m using this rhetorical device, adding “ism” to a word in order to illustrate how we turn a legitimate thing in God’s good world that functions properly into an ideology that damages us and deforms our society. Again, for instance, militarism is condemned repeated in the Bible as it turns military might into something to be trusted; an ideology of idolatry. Economism is that tendency where in consumer capitalism, economic growth is seen as the engine by which everything runs and things that ought not be reduced to their financial side are seen that way. I once heard Os Guinness talk about how he knew a person who literally told a friend how much she could have made if she were working while she was having a glass of wine with her friend, putting a “price” on the hour of fellowship. The best treatment of this, succinct and powerful, can be found in chapter 9 of The Transforming Vision: Developing a Christian Worldview by Brian Walsh & RIchard Middleton (IVP; $16.00.) I am pretty sure they get this worldviewish cultural criticism from the legacy of thinkers in the tradition of Kuyper and his social philosophy. I think it is important for anyone who wants to be cultural wise and discerning in our confusing modern times.

Here is another example of how this helps us evaluate common practices and to discern if idolatry and muddled thinking are having consequences. Neo-Calvinist philosopher (yep, another one) James K.A. Smith in The Devil Reads Derrida and Other Essays (Eerdmans; $18.00) has a brilliant essay on why colleges ought not describe their students as customers or consumers and why education is not about consuming knowledge. (He wrote this piece, by the way, in the newspaper of the college where he is employed, since their admission department, like many throughout the country, had been using these terms in their literature. A bit of a controversy ensued. Just like in Kuyper’s day—ha!)

Using lingo that is appropriate in a business setting to refer to something that is decidedly not a business setting betrays a spirit of reductionistic idolatry, he maintains, and leads to a confusion of spheres. Smith’s Kuyperian roots enabled him to be prophetic in his critique of how we have too often adopted a consumerist model for education or, even, church life (as in church shopping or wanting to get something out of worship.) To talk about customers and profits is fine in economic institutions (although, as we attempt to model, even business interactions with customers are more than mere financial transactions, and even the economic side of life must be approached as holy ground, with relational care.) Schools or churches or non-profit organizations all have economic dimensions to be sure, but their essence is something else, and dare not be reduced to finances. Read that chapter of Smith’s book and you will learn much about the reformational heritage of prophetic discernment. Or, if you like the postmodern turn of a phrase, call it Kuyperian deconstruction. It is something neo-Calvinists are often quite good at.

SPHERE SOVEREIGNTY

As you can see, this concern about idols and the proper function of different spheres (should a family be run like a platoon as in The Sound of Music? Should a Bible study be a therapy group? Should a church be run like a business?) is one thorny area and professor Mouw’s good descriptions of Kuyper and how his framework of soevereiniteit in eigen kring—loosely translated as “sphere sovereignty”—can help us know what to promote when seeking cultural reformation.

Saying a business or a government or a sports team or a church should be what it is called to be is a very, very valuable thing to say and if you have insight about this you will help break the impasses common in our tense times. It amazes me how many political controversies seem stuck without adequate definition of who should do what, what things are supposed to be and what they are s

upposed to be doing.

Again—just to make the point in a simple way—think of what a Little League or school football team is supposed to be about. Playing, right? Making money? No. Teaching values? Well, it happens, but that isn’t the point. Making statements about community pride, with team spirit and boosters? Well, I suppose that’s fine, but, again, that doesn’t trump the calling of sport itself, the (God-given) point: to have fun through playful recreation. Should enhancing a school’s reputation or the parents self-image but the point. Duh. Should the business enterprise overly influence sporting events, as if sports is essentially a money-maker? Or, to change the sphere, should economics guide the development of popular arts, making movies mostly to make money, funding recording acts only on the likelihood that they will sell? Ahhh, where are the Dutch dams and dykes when we need em?

team is supposed to be about. Playing, right? Making money? No. Teaching values? Well, it happens, but that isn’t the point. Making statements about community pride, with team spirit and boosters? Well, I suppose that’s fine, but, again, that doesn’t trump the calling of sport itself, the (God-given) point: to have fun through playful recreation. Should enhancing a school’s reputation or the parents self-image but the point. Duh. Should the business enterprise overly influence sporting events, as if sports is essentially a money-maker? Or, to change the sphere, should economics guide the development of popular arts, making movies mostly to make money, funding recording acts only on the likelihood that they will sell? Ahhh, where are the Dutch dams and dykes when we need em?

INTEGRATION AND PERSONAL WHOLENESS

There is a quite practical side to thinking about the architecture of God’s creation as a many-splendored diversity of institutions. Besides helping us get a handle on what various institutions should be about, and helping us discern when there is idolatry and reductionism and dysfunction. Such a robust social philosophy affirming the rights and limits of various institutions in the various spheres that make up society also gives us some way to gladly resist the fragmenting influences of our many callings and obligations. How do we keep our head on straight when we wear so many hats? How do we find an integrated wholeness when we affirm God’s role in so many diverse callings into so many sides of life? How do the various sides of our lives relate?

Mouw puts it like this, insisting on “a crucial point about the many-ness of reality, namely, the teaching set forth so clearly in the Apostle’s affirmation of the supreme Lordship of Christ. The Son of God is the unifying and integrating One; “in him all things hold together.” Colossians 1:17.)

He continues,

This does not mean that the integration comes easily. Contemporary life is very complex. I struggle with that complexity all the time. How do I tie together all of the varied roles that are so much part of my everyday life. I am, among other things, a husband, a father, a grandfather, a teacher, an administrator, a church member, and one who needs rest and recreation. How do I set my priorities among these many fragments.?

It’s not easy. But as a Christian I have to take these questions to the Lord. I know that he holds it all together and that by seeing all of these things in the context of his integrating Lordship, I can continually sort things out. I don’t simply have to give in to the many-ness that has no ultimate coherence.

A quick aside: as I was thinking of writing this I was going to go on a tangent, which I then deleted, noting that so many family books, for mothers and fathers, suggest that their home-life is more important than their work lives. (Especially for women.) Or, sometimes, there are books on vocation and work that don’t particularly honor our calling to home-making. Few books get it right, helping us with our many-sided vocations. I thought of  one brave Christian book that exposes this tension as unnecessary, a fine book mostly for mothers by Leslie Leyland Fields called Parenting is Your Highest Calling (And Eight Other Myths That Trap Us in Worry and Guilt) published by Waterbrook Press ($13.99.) The book made sense (and was wonderfully written) and, as I said, it seemed to be an example that could fit in here, talking about balancing legitimate callings and offices and tasks, just like Mouw says. I was going to mention it, but then deleted it (trying to cut down the digressions, you know.) And then I saw the comment posted on yesterday’s column by who else but Ms Fields herself who (who knew?) reads BookNotes! Was she reading my mind? She commented that she read Kuyper in college and that his views have significantly shaped her work. Ahhh, I shoulda seen that coming! You see, this stuff matters and can really make a difference. That one of the wiser books on parenting these days is by a woman who is a Kuyperian—well, there you have it. Thanks, Leslie!

one brave Christian book that exposes this tension as unnecessary, a fine book mostly for mothers by Leslie Leyland Fields called Parenting is Your Highest Calling (And Eight Other Myths That Trap Us in Worry and Guilt) published by Waterbrook Press ($13.99.) The book made sense (and was wonderfully written) and, as I said, it seemed to be an example that could fit in here, talking about balancing legitimate callings and offices and tasks, just like Mouw says. I was going to mention it, but then deleted it (trying to cut down the digressions, you know.) And then I saw the comment posted on yesterday’s column by who else but Ms Fields herself who (who knew?) reads BookNotes! Was she reading my mind? She commented that she read Kuyper in college and that his views have significantly shaped her work. Ahhh, I shoulda seen that coming! You see, this stuff matters and can really make a difference. That one of the wiser books on parenting these days is by a woman who is a Kuyperian—well, there you have it. Thanks, Leslie!

THE STATE AND CIVIL SOCIETY

Well, Mouw explores Kuyper’s view of the state within this “many-ness” view which honors the unique significance of various social spheres. I’ve already implied what people should know from their Bibles, that the state is not unlimited, but it does have Godly authority to meddle, if you will (that phrase implies illegitimacy, though, so it isn’t adequate.) It can obviously overstep its bounds—that is the concern of the U.S. Tea Party movement, specifically, and conservatism, generally, and they are right to be concerned. (One doesn’t need to be a  Kuyperian to get that!)

Kuyperian to get that!)

Yet—if you will allow me to improvise on a generally Kuyperian note—it is wrong for conservatives to suggest that the government is somehow illicit to levy taxes. It isn’t “theft” as some conservative bloggers say. “They” don’t “take” our money. Such common ways of putting it betray large and I believe unbiblical assumptions about the role of the state and the nature of taxes. We are commanded in the Bible to pay them gladly. (Apparently Brian McLaren said that last week at the Wild Goose Festival and within days the conservative Institute on Religion and Democracy reported it as if it was looney. Kuyper-Calvinists, I’d think, would agree with McLaren.) Of course we must have vibrant and vigilante public conversations about prudent and just tax policies and expenditures, but, in principle, we should affirm a limited government with serious duties. It is one of the clearer points of a Christian social philosophy that the idea of the state is given to us as a gift from a good God; whether it should be large or small is really not the point, at least not at first, since different cultural contexts may demand different forms of governance. To be somehow against the government seems, to Kuyperian ears, as near blasphemy, like saying one is against the family, or against the church, or against businesses. Mr. Mouw is more diplomatic here than I am and doesn’t step on toes…

Mouw is knowledgeable about this and he explains it better than I do. I hope you care about your citizenship enough to want to think this through. Whether you currently hold conservative or progressive tendencies, I believe this portion of Abraham Kuyper: A Short and Personal Introduction could help.

For those who want a more serious collection of essays about these complex theories, see the important first volume in the on-going series coming out of Princeton’s Kuyper Center, The Kuyper Center Review: Volume One: Politics, Religion, and Sphere Sovereignty edited by Gordon Graham (Eerdmans; $24.00)

important first volume in the on-going series coming out of Princeton’s Kuyper Center, The Kuyper Center Review: Volume One: Politics, Religion, and Sphere Sovereignty edited by Gordon Graham (Eerdmans; $24.00)

CIVIL SOCIETY

One important part of this that Mouw points out is that this approach (or something somewhat like it) has been explored in recent decades by those who are interested in mediating structures. (That would be Peter Berger, for instance, who Pete Steen was very excited about in the early 80s.) Or, more recently, by those writing about civil society. I hope you’ve heard of the book Bowling Alone: The Collapse and Revival of American Community by Robert Putnam (Touchstone; $16.00.) which Mouw mentions. There you have an important view that assumes the legitimacy and social capitol gained by strong mediating structures, voluntary associations, civil institutions, and other groups that are somehow between the sole person in her family and the large institutions of government. Putnam expresses wise concern about what happens to a society where these associations and mediating organizations aren’t strong. (The title of the book comes from his research that even thought the sport of bowling was on the rise in the 1990s, commitment to bowling leagues was down; people aren’t joining associations like they used to and our mediating structures are waning. Think of the decline of any number of organizations, from neighborhood groups, churches, the PTA to the local grange or service clubs or scouting organizations. Hence, his title about the “collapse of community.”)

By the way, Jon Chaplin has an excellent, serious chapter in the aforementioned Kuyper Center Review Volume One on this very topic of Kuyper and civil society. Great!

These civil society institutions, mediating structures, and third places, are important (and when they are strong we do not need as intrusive of a government.) This is important in the views of conservatives (they help us get away from an overbearing state) and for liberals (who love local, populist, organic groupings.) Some who emphasize this are calling themselves communitarians. An off shoot of that is the “crunchy con” movement, a blend of small-is-beautiful localism and resistance to consumerism from a socially conservative motivation. All of these—from Peter Berger to Robert Putnam to Wendell Berry–can be appreciated and deeply valued if one has something akin to a Kuyperian view of how the state is important but limited.

Kuyper loved supporting associations and groups and networks. Such an affinity is something many should support and helps us begin to imagine ways of thinking about social change and public life that isn’t necessarily wedded to Republican or Democratic parties or programs. Mouw isn’t being cheap when he says that Kuyper’s view really does open up a “third way” between the typical left and right, beyond liberals and conservatives. I know I am hungry for such a perspective and ethos. I long for somebody who knows how to develop a programmatic agenda for such a breath of fresh air in our culture wars. It seems to me that the mostly neo-Calvinist Center for Public Justice (CPJ) is the finest civic organization that is working out of an Kuyperian view of social institutions and the high calling and limits of the State. I don’t agree with them on some things, but they still are the most extraordinary group of its kind.

Here is Mouw, in a very short chapter entitled “Placing Kuyper Politically.”

It is difficult to read what Kuyper says about the proper functions of the state without trying to “place” him with reference to contemporary debates. Given the kinds of things Kuyper said in his nineteenth-century context, where would he locate himself today on the “liberal” to “conservative” spectrum of views in the twenty-first century?

For many of us who take his views on political matters seriously, this is no question of idle speculation. It is a question about us. And the question–about Kuyper himself and about those of us who look to his views for contemporary guidance—is difficult to answer clearly.

The left-versus-right dilemma is not unique to Kuyperians. It is a problem for many evangelicals these days. We care about the poor. We are often critical of the military actions taken by our governments. We support environmentalist policies. We oppose racism and gender discrimination.

But we often find ourselves aligning ourselves with concerns that get expressed on the right. We worry about the sexual trends in our society. We oppose abortion-on-demand. We speak out against the naturalistic and secularist biases that often seem to rule the day in the media and the world of education.

Again, that is true for many evangelicals—Mennonites, Baptists, Pentecostals, Wesleyans—as well as friends in the Catholic community. But for some of us, the Kuyperian view of the role of the state also figures into the way we se many of these topics.

CONCERN FOR THE POOR AND THE CALL TO JUSTICE

One of the places Kuyper seems pretty unique is in his passionate concern for the poor and oppressed and how that shapes his proposals. As I’ve implied, it doesn’t seem that Kuyper advocated what today we would call a big government or the “welfare state” of the liberal Democrats. Yet, he realized that sometimes the government simply must do things that other spheres are failing to do; he realized that “let private charity take care of things” wasn’t adequate or normative, given the institutional-structural-systematic realities of the way human societies work.

Mouw has some spectacular quotes from Kuyper here, and he tells us about an importan t book written in the end of the 19th century called Christianity and the Class Struggle (a speech Kuyper gave to the Christian Social Congress in 1891.) He is clearly opposed to Marxism. But he also believes that the state has Bibically-given mandates and things to do, especially if other spheres in others sides of life fail and folks are oppressed. This short Kuyper book is still available, recently given new striking cover art, under the title The Problem of Poverty; translated by CPJ’s James Skillen (Dordt College Press; $10.00.) It is remarkable how such an old resource can be so very relevant.

t book written in the end of the 19th century called Christianity and the Class Struggle (a speech Kuyper gave to the Christian Social Congress in 1891.) He is clearly opposed to Marxism. But he also believes that the state has Bibically-given mandates and things to do, especially if other spheres in others sides of life fail and folks are oppressed. This short Kuyper book is still available, recently given new striking cover art, under the title The Problem of Poverty; translated by CPJ’s James Skillen (Dordt College Press; $10.00.) It is remarkable how such an old resource can be so very relevant.

There is enough in these pages of Mouw’s overview indicating that Kuyper is generative for contemporary thinking about a Christian perspective on citizenship and the call to public justice and prudent statecraft. Mouw is a good voice in this, although those on the far right may think he reads and appropriates Kuyper wrongly. (The thoughtful folks at the generally Catholic, free market-oriented Acton Institute will be hosting a Kuyper conference in the fall, I’m told, to illustrate their own reading of Kuyperian social theory about liberty, morality and markets.) Mouw has thought this through for years and his informal take in this personal book is great for beginners. Or those who want to wrestle with the possibility of refreshing alternatives and third ways. As you can tell, I think it is important and we commend it to you and yours.

THE ANTITHESIS AND COMMON GRACE

Another very important feature of Kuyper’s thought was his dual emphasis on two seemingly contradictory Biblical themes. Mouw is clear about it, but I’ll try to highlight my sense of it. Read Mouw on Kuyper, though, to get it right!

Kuyper and his associates stressed the radical call to God’s people to be distinctive, holy, faithful, and non-aligned with any sinful group or idolatrous ideology. Kuyper referred to this as “the antithesis” realizing that there are two large camps in the world, those who bow the knee to the Lordship of Christ and all others; there is a struggle for human history between the Kingdom of light and the kingdom of darkness. This dire call to rigorous orthodoxy and social purity may rather naturally lead to a disengagement with the world and yields what some might call a “fighting fundamentalist” attitude.

However Kuyper equally talked about “common grace” which is to say that since all truth that is true is so because of God, and that God in mercy allows this dysfunctional old world to experience measures of goodness and hope, we can celebrate and affirm and cooperate with any signs of life that we come across. This may rather naturally lead to an engagement with the world and yields what some might call an “accommodating liberal” attitude.

Dr. Mouw doesn’t explore this in great depth, but it does seem to me that the call to holiness and resistance to sin coupled with a glad acceptance of the idea that goodness abides even in a fallen world, can create the exact sort of “in but not of” the world approach that Jesus prays for at the end of the gospel of John. (Do you recall that out of print book published by Augsburg-Fortress in the 80s by Richard Mouw that I mentioned in the last post entitled Called to Holy Worldliness? Guess this is where that title comes from.)

Tullian Tchividjian’s excellent book Unfashionable: Making a Difference in the World by Being Different (Multnomah; $18.99) gets at this wonderfully, by the way, and it should come as know surprise that he cites Kuyper. This is transformational stuff, not moderate balance or a mushy blend of liberal and conservative impulses. This is a radical, robust, engaged way of thinking about our calling in the world (even if you never call it Kuyperian!) Highly recommended!

Tullian Tchividjian’s excellent book Unfashionable: Making a Difference in the World by Being Different (Multnomah; $18.99) gets at this wonderfully, by the way, and it should come as know surprise that he cites Kuyper. This is transformational stuff, not moderate balance or a mushy blend of liberal and conservative impulses. This is a radical, robust, engaged way of thinking about our calling in the world (even if you never call it Kuyperian!) Highly recommended!

Antithesis. Common Grace. In Mouw’s explaining pages these words arem’t arcane jargon but are tools of the trade, helpful shared vocabulary to help us navigate the good, the bad and the ugly. I gather than many of our readers want to be more engaged in fruitful discernment and robust conversations about the things that matter most. This will help, I’m sure. If this really intrigues you, check this out: The Acton Institute has partnered with Kuyper College and they are embarking on a several year project of translating from the Dutch the three volume work of Kuyper on common grace, (De gemeene gratie.) You can sign up for updates, even follow them on the Common Grace facebook page.

For a good bit of pondering on this matter of common grace (does God really like baseball, jazz music, a fine meal?) Rich Mouw’s own wonderful, wonderful He Shines in All That’s Fair: Culture and Common Grace (Eerdmans’ $14.00) is a must. I mentioned in the previous post and recommend it again, now. Then, you might want to study the serious collection of articles about Bavinck and Kuyper and the legacy of their neo-Calvnist views of common grace found in the diverse anthology from the Princeton conferences, The Kuyper Center Review: Volume Two: Revelation and Common Grace edited by John Bowlin (Eerdmans; $36.00.) It is a pretty amazing bit of historic scholarship with great contemporary significance.

AGGIORNAMENTO

Even as Mouw is helpful in explaining Kuyper’s basic concepts and why they are useful as a way to talk about contemporary institutions, God’s call to wholistic discipleship and the structure and tone of public witness, he also is helpful in exposing weaknesses of Kuyper and, when appropriate, how to update Kuyper for our postmodern age.

He starts out this second section of the book describing what the Roman Catholic church during the years of Vatican II called a season of aggiornamento, or updating.

Mouw is candid about some of Kuyper’s faults and is eager in some cases to seriously reform his work. This is nothing new within any tradition and even within Kuyper’s own day one of his young colleagues was the very important Herman Bavinck, who himself often spoke with a less strident tone and a wider graciousness than Kuyper sometimes did. He was a partner in Kuyper’s large efforts but he refined and restated some of Kuyper’s views. Was the updating beginning even then? Of course.

And, by the way, the conversation and re-appropriation continues even now as more conservative Reformed folks are rediscovering Bavinck. A long-awaited, masterful biography of him has recently been published and has gotten rave reviews. See Herman Bavinck: Pastor, Churchman, Statesman, and Theologian by Ron Gleason (P&R; $29.99.) Bavinck’s hefty four-volume Reformed Dogmatics have been re-edited and re-issued by Baker Academic and a large one-volume abridgment edited by Kuyper scholar John Bolt is now available (Baker Academic; $59.99.) It is “the supreme achievement of its kind” (J. I. Packer) and stands alongside Kuyper as essential Dutch Reformed scholarship. Some of our edgy emergent guys say that to go forward we need to go backwards; who hasn’t heard the phrase “ancient-future” faith? Maybe this is part of that, eh?

And, by the way, the conversation and re-appropriation continues even now as more conservative Reformed folks are rediscovering Bavinck. A long-awaited, masterful biography of him has recently been published and has gotten rave reviews. See Herman Bavinck: Pastor, Churchman, Statesman, and Theologian by Ron Gleason (P&R; $29.99.) Bavinck’s hefty four-volume Reformed Dogmatics have been re-edited and re-issued by Baker Academic and a large one-volume abridgment edited by Kuyper scholar John Bolt is now available (Baker Academic; $59.99.) It is “the supreme achievement of its kind” (J. I. Packer) and stands alongside Kuyper as essential Dutch Reformed scholarship. Some of our edgy emergent guys say that to go forward we need to go backwards; who hasn’t heard the phrase “ancient-future” faith? Maybe this is part of that, eh?

RACE and APARTHEID

What are the key problems with Kuyper? As I said in the previous post, he was ill informed about African peoples and Mouw names that sin for what it is. Kuyper sometimes gets blamed for how some used the “sphere sovereignty” idea to create apartheid in the Dutch colonized South Africa. Mouw, well known as an advocate of racial justice and human rights rightly condemns the failures of the Dutch Reformed for this. However, he notes that Kuyper did not overtly support the formation of apartheid late in the 19th century and his speaking about South Africa was mostly limited to his support for the Boer liberation from the British. (He despised British colonialism and yet admired the liberal Democratic Christian leader, Gladstone.) Was Kuyper’s support for nationalism among the Transvaal (against British colonialism) co-opted by those with unenlightened racial attitudes? Here is a long and scholarly work by a substantive historian from the Vrjie University on this for those that want a detailed study of those years.

Mouw offers as a way towards aggiornamento, the importance of knowing and hearing the voices of black Kuyperians. Reformed South Africans like Alan Boesak and H. Russell B

otman are cited and we get to hear how they appropriated Kuyper in their own struggle for an indigenous, African, contextualized, Reformed theology.

One of the most interesting lectures I have heard on this was delivered by Wheaton College scholar Vincent Bacote, a North American black Kuyperian. Bacote has written widely on Kuyper and it was no surprise to see Mouw cite him approvingly. Bacote, by the way, also is keenly aware of Kuyper’s work on the Holy Spirit, another contribution that Mouw notes. Mouw knows many Pentecostals and thinks that somehow a renewed interest in that might enhance neo-Calvinism. (He cites Al Wolters, in fact, who says that as well.) Could Kuyper offer clues to how a renewed awareness of the Holy Spirit and a renewed call to racial justice might combine? What would Kuyper say about the Belhar Declaration. I wish Mouw might have weighed in on that…

scholar Vincent Bacote, a North American black Kuyperian. Bacote has written widely on Kuyper and it was no surprise to see Mouw cite him approvingly. Bacote, by the way, also is keenly aware of Kuyper’s work on the Holy Spirit, another contribution that Mouw notes. Mouw knows many Pentecostals and thinks that somehow a renewed interest in that might enhance neo-Calvinism. (He cites Al Wolters, in fact, who says that as well.) Could Kuyper offer clues to how a renewed awareness of the Holy Spirit and a renewed call to racial justice might combine? What would Kuyper say about the Belhar Declaration. I wish Mouw might have weighed in on that…

WORLD-VIEWING

I will not belabor this, but Mouw is very, very good in the few pages where he invites us to think of new ways to talk about worldview. Kuyper, as I mentioned in the last post, was a seminal author to have introduced North American’s to the notion that Calvinism was more than a system of theological thought but was a robust way of being in the world. The very phrase and much of the understanding of the world worldview has become associated with certain very conservative social movements and with very dogmatic ways of thinking and Mouw has suggested that Kuyperian neo-Calvinists might use the phrase world-viewing (as in beholding) in order to capture a more imaginative and dynamic vision of how our vision of life shapes our ways of living.

I am grateful for the influence this worldview perspective has had for my own spiritual and intellectual journey. But I have to admit that some of the talk about worldview makes me a little nervous these days. When I hear folks insist on the need for all of us to “have” a Christian worldview, I worry about the static picture that evokes. It suggests that a worldview is something we can possess, a thing we can “own” or just “get.” That in turn gives the impression, I fear, that having a worldview means that we are equipped with a set of answers, or the capacity to generate those answers fairly easily, when we encounter important questions. I don’t like the “packaged” feel of all that.

Mouw isn’t backing off the approach he learned from the Princeton Stone Lectures, Calvinism as a Life System, the earlier title of what is now known as Lectures on Calvinism (Eerdmans; $15.00.) But it is delightful (and not surprising) that Mouw cites the Catholic thinker Joseph Pieper, who uses a Latin phrase from the ancient mystics: ubi amor, ibi oculus—roughly, “where there is love, there is seeing.” That he wants a more dynamic and embodied view of hosting questions in light of a Christian way of seeing is not surprising, either. Friends of Mouw—some of them clearly in the neo-Calvinist and Kuyperian tradition— called a conference about this, in fact, a few years ago and many of the chapters in the book that came from it explored these very things. I’ve noted it before and continue to think that much of it is fantastic. If you want a good example of significant updating of insights cleaned from the reformational movement, see After Worldview edited by Matt Bonzo and Michael Stevens (Dordt College Press; $13.00.) Mouw should have been at that event and, to be honest, if Pete Steen were alive, he would have been. It is a very thoughtful little book that would be a good follow-up to Mouw’s “World-viewing” chapter here.

Mouw isn’t backing off the approach he learned from the Princeton Stone Lectures, Calvinism as a Life System, the earlier title of what is now known as Lectures on Calvinism (Eerdmans; $15.00.) But it is delightful (and not surprising) that Mouw cites the Catholic thinker Joseph Pieper, who uses a Latin phrase from the ancient mystics: ubi amor, ibi oculus—roughly, “where there is love, there is seeing.” That he wants a more dynamic and embodied view of hosting questions in light of a Christian way of seeing is not surprising, either. Friends of Mouw—some of them clearly in the neo-Calvinist and Kuyperian tradition— called a conference about this, in fact, a few years ago and many of the chapters in the book that came from it explored these very things. I’ve noted it before and continue to think that much of it is fantastic. If you want a good example of significant updating of insights cleaned from the reformational movement, see After Worldview edited by Matt Bonzo and Michael Stevens (Dordt College Press; $13.00.) Mouw should have been at that event and, to be honest, if Pete Steen were alive, he would have been. It is a very thoughtful little book that would be a good follow-up to Mouw’s “World-viewing” chapter here.

CAN THE CHURCH SUPPORT THE LAITY IN DAILY WORK

I do not have time to explore in detail the final chapters of Abraham Kuyper: A Short and Personal Introduction. I’m sorry I’ve not been concise—I should take a lesson from Rich Mouw. Yet, these last chapters are among the most stimulating in the book; I will be brief.

If you have followed Mouw’s call to take Kuyper seriously about God’s ordaining structure to social life, that institutions and various spheres of society really matter, and that each of us are called to live faithfully within those God-given arenas, then you will naturally see that the local church—a central but not the only institution of importance to God’s work—has a job to worship, teach, offer sacraments and opportunities for deep community, so that God’s people can be scattered into the various fields and areas of service in which they find themselves. Remember “sphere sovereignty”? The church musn’t (and, indeed, cannot) do everything.

Mouw takes up Kuyper’s passion for the ordinary person and asks how pastors and congregational leaders can equip journalists, scientists, artists, business people, farmers and the like. What is the relationship between the local church and the professional callings of lay people? Can we expect the local church to really teach their members how to serve God as insurance salesmen, medical providers, researchers or home-makers? What does the pastor know about these things?

Kuyper was big on professional associations and believed that it was the duty of Christian disciples to organize with other brothers and sisters in public life.

The post-WW II Dutch immigrants to Canada and the United States naturally were surprised (or so Steen used to tell us) to realize that most North Americans had sold out to the spirit of individualism. There were no Christian farmers associations, no serious Christian newspapers, no organizations to witness to Christ in political life, no alternatives to the secular labor unions—in public, Christian acted like they were no longer the body of Christ and aligned themselves with whatever political or cultural agencies they liked.

So, often uneducated workers and lay people started a generations-long effort to provide ways in which Christian persons could unite within various professional spheres and could live a whole-life way of life. Some of us may be sanguine about such plausibilities (although it does happen: the CLAC, the Christian Labor Union of Canada does excellent, just, collective bargaining based on uniquely Christian principles about the dignity of work and being non-adversarial. They are, as the Bible predicted, hated by others for their gentle witness in the economic realm; do watch the video clip about them. The Christian Farmers Federation (again, a largely Kuyperian organization) has been asked by provincial governments to draw up proposals for renewed agricultural policies.) It was (among others) Dutch Protestants who organized groups decades ago like CIVA (Christians in the Visual Arts) and the NACPA, the National Association of Christian Political Action, which eventually became CPJ. Some of these same Dutch immigrants–Pete Steen among them, before he wandered into the orbit of the Pittsburgh campus ministry,

the CCO—already influenced by the profound thinking within the reformational movement inspired by the philosophy department at the Vrije U. started a seriously rigorous grad school that offers Masters and PhD degress, Toronto’s Institute for Christian Studies. Anyway, Kuyper’s vision of lifting up the role of the ordinary workers and faith-based associations for professionals in their careers and Mouw’s reflections on how church leaders could help do that in our contemporary setting are very suggestive and very important. He doesn’t mention any of this unique organizations, but I wanted you to hear of them since Abraham would have been pleased.

Beyond helping workers, Mouw shows other innovative ways we might use Kuyper’s ideas in some innovative ways, ways that can bring justice and healing and hope. For instance, he notes that an updated, reformed Kuyperianism would not presume a “Christendom” model. It is not Constantinian. He explains that well, and it is helpful. A neo-Calvinist worldview would also invite (as Kuyper and Bavinck both did) interest in Islam and interfaith dialogue. And it would affirm the arts, being strategic about ways to sponsor and assist those who are exercising their creative callings for the common good. All of this would take great cultural patience, which is the title another short section of Mouw’s book.

UNDER THE CROSS I have often said that I love Dr. Mouw’s book Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World (IVP; $16.00.) And I have often said that I love his chapter in that book “Abraham Kuyper, Meet Mother Teresa.” I was thrilled, then, to see that in Mouw’s last chapter of this little Kuyper book he uses a quote and story from that chapter. Yes, Mouw celebrates the impact that Kuyper’s dramatic reminder that Christ claims “every square inch of creation” by crying “Mine!” But he worries about triumphalism, about arrogance, about the loss of the servanthood spirit embodied best by the saint from Calcutta. Such arrogance, Mouw writes, “can blind us to the need to go out and suffer in those many broken regions of creation where the homeless set up their crude sleeping shelters, where people grieve, and where the abused and the abandoned cry out in despair. Jesus calls us to join him there, for those square inches—and those who inhabit them—belong to him, too.”

I have often said that I love Dr. Mouw’s book Uncommon Decency: Christian Civility in an Uncivil World (IVP; $16.00.) And I have often said that I love his chapter in that book “Abraham Kuyper, Meet Mother Teresa.” I was thrilled, then, to see that in Mouw’s last chapter of this little Kuyper book he uses a quote and story from that chapter. Yes, Mouw celebrates the impact that Kuyper’s dramatic reminder that Christ claims “every square inch of creation” by crying “Mine!” But he worries about triumphalism, about arrogance, about the loss of the servanthood spirit embodied best by the saint from Calcutta. Such arrogance, Mouw writes, “can blind us to the need to go out and suffer in those many broken regions of creation where the homeless set up their crude sleeping shelters, where people grieve, and where the abused and the abandoned cry out in despair. Jesus calls us to join him there, for those square inches—and those who inhabit them—belong to him, too.”

Interestingly, Mouw cites in this last good chapter a piece by scholar Mark Noll who, in a Kuyper Lecture given to the Center for Public Justice, reminded the excited Kuyperians that Christ pointed “Mine” in a hand that was scarred. To follow Jesus, Dr. Noll said, is to remember “the road to Calvary that the Lord Jesus took to win his place of command.” This isn’t a “culture wars” mentality and it isn’t about “taking over” any square inches for Christ. CPJ and Noll and Mouw and Kuyper all cite the teaching of Jesus about the wheat and the tares: we live in a time which calls for patience. It is not ours to rip up or root out. We are called to servanthood, to gentleness, to sacrifice.

A GOOD DEATH, IN CHRIST

Mouw’s final chapter is called “A Kuyperianism Under the Cross.”

The great scholar, statesman, thinker, social reformer, Dr Abraham Kuyper himself, Mouw tells us, reminds of this call to Christ-like suffering and service over and over, but most poignantly in his own death. In his last dying moment he raised his hand and pointed to a crucifix. It is a good ending to a good life and it is a fine ending to a lovely little book. Mouw, as I said in the last post, is sensitive to matters of ordinary piety, is an intellectual and Christian leader but is also a simple man of God. He loves his Savior and he speaks often of the central things of faith. That Kuyper, too–who wrote the beloved devotional Near Unto God, you will recall–was in his death confident of the atoning work of his Lord is a sweet truth. Social reformer, journalist, sociological critic, public intellectual, international diplomat, yes, yes. But at the end, he pointed to Jesus and his cross. This was a great man, indeed.

us, reminds of this call to Christ-like suffering and service over and over, but most poignantly in his own death. In his last dying moment he raised his hand and pointed to a crucifix. It is a good ending to a good life and it is a fine ending to a lovely little book. Mouw, as I said in the last post, is sensitive to matters of ordinary piety, is an intellectual and Christian leader but is also a simple man of God. He loves his Savior and he speaks often of the central things of faith. That Kuyper, too–who wrote the beloved devotional Near Unto God, you will recall–was in his death confident of the atoning work of his Lord is a sweet truth. Social reformer, journalist, sociological critic, public intellectual, international diplomat, yes, yes. But at the end, he pointed to Jesus and his cross. This was a great man, indeed.

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

any book mentioned above

2O% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333