Learning to Walk in the Dark Barbara Brown Taylor (HarperOne) $24.99 20% OFF our sale price, $19.99

You are buried under all this light, all these lines… “Loneliness and Alcohol” Jars of Clay

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight, and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings. “To Know the Dark” Wendell Berry

I will give you the treasures of darkness and riches hidden in secret places, so that you may know that it is I, the Lord, the God of Israel, who call you by your name. Isaiah 45:3

This book with a beautiful cover arrived a week ago and despite a heavy and very late-night schedule of setting up displays to sell books at events, some speaking and some family stuff, I carried it with me, wishing just to dip in a tiny bit. Even a page of Barbara Brown Taylor can make one glad to be a bookseller; her eloquent, crisp, prose is so good – clever, but not overly so, lively with fabulous metaphors and similes without being gaudy, her sly turn of phrase can just takes one’s breath away. I am not the only one who will read anything she writes.

ago and despite a heavy and very late-night schedule of setting up displays to sell books at events, some speaking and some family stuff, I carried it with me, wishing just to dip in a tiny bit. Even a page of Barbara Brown Taylor can make one glad to be a bookseller; her eloquent, crisp, prose is so good – clever, but not overly so, lively with fabulous metaphors and similes without being gaudy, her sly turn of phrase can just takes one’s breath away. I am not the only one who will read anything she writes.

And her ideas? They shift between uncommon good sense and the pretty provocative. You may know she is a former Episcopalian pastor who left parish ministry and is a progressive, thoughtful religion professor and very popular speaker on the mainline denominational circuit. Typical evangelical readers who read her may be teased into re-thinking some things, and nearly all readers will resonate with fresh ideas that are striking, and often quite sensible. Her writing is almost always an energizing, lovely, inviting blend of beautifully-rendered, gracious, open-minded insight, layered within great storytelling that approaches memoir. Agree or not with every point she draws from her experiences, her books are always, always a “must read.” There is a reason she is considered one of the best preachers in America and why she is beloved not only in her own Episcopalian tribe, but across the spectrum of mainline Protestants, emergent, and evangelicals, as well. (No one since Frederick Buechner, perhaps, has had this sort of broad, ecumenical, literary acclaim.) When her book first came out, it was Jonathan Merritt (a Southern Baptist) who first interviewed her for Religious News Service. See part two of his interview, here.

reason she is considered one of the best preachers in America and why she is beloved not only in her own Episcopalian tribe, but across the spectrum of mainline Protestants, emergent, and evangelicals, as well. (No one since Frederick Buechner, perhaps, has had this sort of broad, ecumenical, literary acclaim.) When her book first came out, it was Jonathan Merritt (a Southern Baptist) who first interviewed her for Religious News Service. See part two of his interview, here.

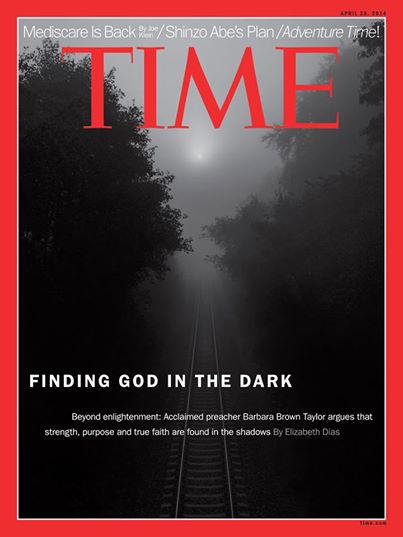

And, as you can see, she was recently on the cover of Time magazine, again attesting to her popularity.

There are books – I am sure you know what I mean – that are pleasurable to read, fascinating, and lovely, just because they are so exquisite or elegant or eloquent; these are so well-crafted that you cannot put them down, even if you don’t agree with them in full, and you are enriched by the art of the writing. (Think also of brilliantly-made films or expert, classic paintings that are wondrous to behold and bring great pleasure and value even if the worldview behind them is less than compelling or good.) We thank God for the gifts of common grace — great writers, poets, storytellers, memoirists, who give us a window into the mysteries of life and offer us pleasure and joy as we read, even if we must read them carefully, with discernment.

And there are those authors who are laden with reliable insight, who hold up important truths, who examine and explore and teach – but, you know, they just don’t have that gift of being a truly great writer. We thank God for these teachers too, glad for the opportunity to wade through their work, knowing it will instruct us wisely, even if it doesn’t sing.

And then – Jubilation! – there are those who combine artful delivery and helpful ideas, who are great writers and good thinkers. These are the books that thrill us most, those rare ones that are pleasing and important to consider; artful and wise. This good combination of style and content really creates a wonderful experience of reading. It is a matter I’ve mentioned before, when form meets function, when the medium and the message have integrity, when a book is good to read, and good for the soul.

Some may put Barbara Brown Taylor in the first category, the sort of writer who is gifted, talented, gloriously interesting, a real joy to read, but with a seductively dangerous worldview, offering a less than theologically-sound perspective while sounding so very good. I realize why some say this as she seems less theologically conventional with each new book. Yet, in my view, she remains a very helpful ally for those of us on the journey to be what God intends, a fine example of what some call “a generous orthodoxy.” I believe it is an honor to spend time with her, even if only on the printed page. (I have met Ms. Taylor, heard her lecture and preach and chatted with her and as those who have met her know, she is a dynamic, gracious presence; I think it is fair to say that much of her lovely personality seeps into her pages. Your really do get to know her a bit through her honest writing.)

gifted, talented, gloriously interesting, a real joy to read, but with a seductively dangerous worldview, offering a less than theologically-sound perspective while sounding so very good. I realize why some say this as she seems less theologically conventional with each new book. Yet, in my view, she remains a very helpful ally for those of us on the journey to be what God intends, a fine example of what some call “a generous orthodoxy.” I believe it is an honor to spend time with her, even if only on the printed page. (I have met Ms. Taylor, heard her lecture and preach and chatted with her and as those who have met her know, she is a dynamic, gracious presence; I think it is fair to say that much of her lovely personality seeps into her pages. Your really do get to know her a bit through her honest writing.)

I believe Barbara Brown Taylor is one who combines artful craft with good insight. Her writing is beautiful and her content is mostly solid. I say that having read all of her major books (and many of her sermons), as a fairly conservative evangelical myself, wanting a view of things that is significantly informed by the Bible. I believe she is more than just a great writer; she is a great writer with great insight. She herself is profoundly rooted in a Biblical sensibility – she has four or five collections of sermons on Biblical texts, after all, and a wonderful book on how to preach. (She helped edit the multi-volume Feasting on the Word lectionary preaching commentaries, too, so she knows well the details of exegesis, Biblical studies, and the multi-layered readings of Biblical texts.) Even when I think she overplays a point, or underestimates another, and I think she misconstrues a text or two in this new one, there is very little in Learning to Walk in the Dark that is truly objectionable, even from the evangelical and Reformed perspective shared by many BookNotes readers.

I start there because at least one prominent review warned that she heads a bit too much into the dark in this book, complaining as she does about the images of light that are so prevalent in the Bible. Granted, she warns about taking too much of the Bible at face value, and she draws on other traditions (mostly Buddhism) to help explore themes of uncertainty and the absence of God. But this should not alarm us; most Hearts & Minds readers know why we should (as the Bible itself instructs and models) read widely, generously, drawing true truth from many sources, and why a mind open to fruitful insight where-ever it pops up is a good and healthy; using our minds well is a righteous practice. BBT gets this right, even if I sometimes wish she’d sound more robust in her description of God as the Triune One seen most clearly in Jesus the King.

L earning to Walk in the Dark is a book about which I am very excited, a reading experience that was for me intense and wonderful; I want to tell you that you should read this book, and that it will be a great experience, an encounter with mystery and self-discovery and, I think, true spirituality. I believe it will be a balm for some who may be drifting from strictly conventional faith or those who resist simple clichés of evangelical piety. I myself was challenged and gripped and moved as I read, listening in to her own tale, her journey exploring darkness. I don’t know of any other book that does this so well, bringing together so much so effortlessly.

earning to Walk in the Dark is a book about which I am very excited, a reading experience that was for me intense and wonderful; I want to tell you that you should read this book, and that it will be a great experience, an encounter with mystery and self-discovery and, I think, true spirituality. I believe it will be a balm for some who may be drifting from strictly conventional faith or those who resist simple clichés of evangelical piety. I myself was challenged and gripped and moved as I read, listening in to her own tale, her journey exploring darkness. I don’t know of any other book that does this so well, bringing together so much so effortlessly.

Taylor makes clear that she intends to explore darkness and night as a legitimate and needed spiritual metaphor. She is in good company, of course: just think of the medieval classic Dark Night of the Soul or the contemporary spiritual memoir Still: Notes on a Mid-Faith Crisis by Lauren Winner, or even Walt Brueggemann who brings Biblical material to fund our efforts to cope with loss.

But Taylor also wants to explore her love of night-time and moonlight (which is to say, literal darkness.) She writes beautifully about creation, in ways that remind us of nature writers like Annie Dillard or Chet Raymo (who she quotes.) This brings her to concerns about the science of sleep and the remarkable dangers of light pollution. And, too, she ruminates on darkness as a psychological reality — fear of the dark, night terrors, dreams, the good and bad of the stuff that dwells deep down. And through storytelling, she invites you to see how it lines up with your own experience and common sense.

Through it all she reminds us of her pet peeve, namely, that darkness is a symbol of all that is bad, troubling, evil, demonic, scary. (Yes, this is in her view because of the Bible, although it is problematic in other faiths and philosophies and current usage as well.) Although the book doesn’t dwell on it, she reminds us that this usage has been hurtful, especially to those with dark skin or those who are visually impaired. What psyche toll does it place upon people of color to be told that black is the color of doubt and demons? That we are to be on guard against darkness? How do blind people feel about the spiritual metaphor of blindness? Why has all of this developed? Why are we scared of the dark?

(That Ms. Taylor is herself at home in the natural world – we learned that in her very first book — and fairly fearless in this regard gives her an advantage, I guess. She tells of gathering eggs from her chickens in the dark, reaching into one nest to feel the cold hardness of a black snake, and it doesn’t faze her a bit. Neither does sleeping in a cabin with a scorpion; “I hope he doesn’t walk in his sleep” is her only note about this. Yikes!)

H er first few pages drew me nicely into this question of from where we get our fear of the dark (and disarmed my skepticism of the project) by using her storytelling art and clean, effective powers of description. She can conjure an image without trying to hard – I am reluctant to call her vivid, as that seems too splashy. As only the very best writers can, she uses her abilities discreetly, and it is so effective. She tells of her mother calling neighborhood kids in at dusk – it was getting “dark” out, of course – and as Barbara returned home, the lights of the house came on. As she describes the feelings of coming in from the dark and the sights and sounds and feelings of those electric sources of light appearing (over the sink, in the living room, the TV room, the nightlight, the warmth and glow and glare each brings) I thought it was 1964 and I, too, was being called in by my own mom standing on the porch in Mullertown. I was hooked by the end of page 2.

er first few pages drew me nicely into this question of from where we get our fear of the dark (and disarmed my skepticism of the project) by using her storytelling art and clean, effective powers of description. She can conjure an image without trying to hard – I am reluctant to call her vivid, as that seems too splashy. As only the very best writers can, she uses her abilities discreetly, and it is so effective. She tells of her mother calling neighborhood kids in at dusk – it was getting “dark” out, of course – and as Barbara returned home, the lights of the house came on. As she describes the feelings of coming in from the dark and the sights and sounds and feelings of those electric sources of light appearing (over the sink, in the living room, the TV room, the nightlight, the warmth and glow and glare each brings) I thought it was 1964 and I, too, was being called in by my own mom standing on the porch in Mullertown. I was hooked by the end of page 2.

I do not know if you will be choked up as you read, but this was a very moving read for me – I wiped away literal tears more than once, and chuckled with recognition more than once. On almost every page I thought, “there, she does it again, using just the right word, surprising us with image and simile, and an understated story, connect previous words or cadences. And, as I’ve said, she raises vital issues, doing on-the-ground theology by way of artful prose and great storytelling. This is a perfect blend of memoir and practical spirituality, fun reading and life-changing re-orientation of our assumptions and attitudes and convictions. At the very least, it reminds us that the waxing and waning of faith — the rhythms of lunar faith — is not bad. It is not even that unusual, if only we had the honesty to say so.

Her sturdy theology is not just “on the ground” in this book, but also above ground, and even underground.

Barbara loves the night sky, and thinks we underestimate the importance of moonlight. There are beautiful passages about star-gazing and various stages of the moons cycles; an episode of laying a blanket out with her husband to watch the moon rise is plainly told, yet beautiful and oddly moving. She reports that it had been twenty years since they had done this. (They could hardly say the reason why, although they knew: “too busy.”) As tears rolled down my cheeks, I too, had to make such a sad admission. Too busy to lay with my beloved under the stars.

There are beautiful passages about star-gazing and various stages of the moons cycles; an episode of laying a blanket out with her husband to watch the moon rise is plainly told, yet beautiful and oddly moving. She reports that it had been twenty years since they had done this. (They could hardly say the reason why, although they knew: “too busy.”) As tears rolled down my cheeks, I too, had to make such a sad admission. Too busy to lay with my beloved under the stars.

One whole chapter is about going to a wild cave with experienced guides, a funky fundamentalist couple who are civil war historians and serious spelunkers. Again, she writes about this beautifully and even though I am as scared of caving as I am of rock climbing, I found this to be a wonderful, wonderful chapter. What she learns about the dark — the very, very dark — is multi-dimensional; she tells of the geology and psychology of caving, the bats and bugs and crevices and water, how her body felt and how the issues of her own interior life arose, sitting in that ancient, black, underground chamber. The bit about a shiny rock she brought up with her, examining it back in her hotel room, was nothing short of brilliant, wonderfully crafted as a bit of writing, and a stand-out, take-away insight from the whole book. Things do look different in the dark, and too much light can prove adverse. Thanks, Barbara, for sharing with us your souvenir from Organ Cave and your experience of “entering the stone.”

Another spectacular chapter narrates the author’s experience participating in an experiential performance art installation which replicates blindness. In this episode, sighted people are given white canes, and enter a very large darkened space, and are asked to follow the sound of a guide (who ends up being herself truly blind, enacting the saying, “the blind leading the blind.”) Participants hear sounds, are asked to engage in common tasks such as shopping in a small grocery store, and crossing simulated streets as car-horns blare. Perhaps you, too, have read accounts of those who are visually impaired – at least the moving works about Helen Keller, and you know how powerful even reading about this can be. This part of the chapter called “The Eyes of the Blind” was riveting, indeed, making me catch my breath and stop to unclench my muscles. I recommend it to you, even for this portion. Taylor goes deeper in her reflections upon this experience by telling us of the important writings of a blind European scholar (captured by the Nazis in 1944) named Jacques Lusseyran (and a book of his writings Against the Pollution of the I.) Barbara’s reflection upon the line from the Book of Common Prayer about “celestial brightness” — “that by night as by day your people may glorify your holy Name…” ends this moving chapter. Nice!

There is a chapter about her trip to the world-famous Chartes Cathedral, and her discovery of the statues of the black Virgins in the underground below the more famous sanctuary. There is a chapter about a night spent in a dark cabin, experiencing natural circadian rhythms. There is a great chapter (“Hampered by Brilliance”) about light pollution. As one who has testified about the value of night sky (at a public hearing trying to stop a local Wal-Mart from encroaching on rural fields) I found this very, very interesting. Did you know that some large sea turtles, after laying eggs, are drawn to the new lights of beach towns — the bars, casinos, strip malls, hotels — thinking that these lights are moonlight shimmering on the water and become stranded, dying in deep sand, rather than heading back to sea as they ought? Her brief look at the ecological dangers of light pollution from poorly managed development was alarming – what to do? (I couldn’t help but think of another great book I read and reviewed recently, Bill McKibben’s Oil and Honey, which not only looked at climate change, but at the beauty of the bees.)

Coming to not fear the dark is part of the solution, whether on a very emotional level (facing the fears about the hard work of attending to grief or other messy feelings) or on a more societal level — literally, why all the extra lights, when they’ve not been proven to stop crime or bring humane flourishing, after all? Why do we have all-night shopping, why do we not sleep well, why are we careening towards more and more, driven by such an impoverished view of progress? Fear of the dark — physically, emotionally, even spiritually — is behind much dysfunction in our culture, and this book gently, through story and memoir and often delightful rumination, points towards healing and hope.

I agree with Shauna Niequist who writes about Learning to Walk in the Dark saying that it is “a gift to every person who’s felt the darkness but not had the words to articulate it, which is to say it’s for all of us.”

I get what Lauren Winner says, too: “Beautiful. Profound. Nourishing. I have needed to read this book for a long time.”

Can it be that twilight and the experience of the absence of light (and the perception of the absence of God) can be generative? Barbara Brown Taylor thinks so. It is pathological to be in denial about the so-called dark stuff, it is foolish to bypass a central part of the human experience. With trust in the benevolence of a very real and present God, we can dive deep.

Taylor writes, “Learning to walk in the dark is an especially valuable skill in times like these – or maybe I should say remembering to walk in the dark, since people of faith have deep pockets of wisdom about how to live through long nights in the wilderness. We just forgot, most of us, once we got where we were going and the glory days began.”

She continues,

The remembering takes time, like straightening a bent leg and waiting for the feeling to return. This cannot be rushed, no matter how badly you want to get where you are going. Step 1 of learning to walk in the dark is to give up running the show. Next you sign the waiver that allows you to bump into some things that may frighten you at first. Finally, you ask darkness to teach you what you need to know. If you have never had a spiritual director before, you have started near the top. Let this one guide you and you will soon have new companions as brave and curious as you are about the nightlife of your soul.

Taylor helps us see what she means in many, many ways, with lots of good examples. Her narration of being a barmaid in underground Atlanta while being a seminar student — and the ways being a barmaid and pastor are in some ways similar — was just wonderful, even if she has written about this before. Her willingness to tell about her own weird nearly Pentecostal conversion and early faith formation (which perhaps traumatized her with sermons against dark things, demons, dangers) was brave and candid, and this, too, points us towards a more balanced approach to things that go bump in the night. She gives further pointers about listening to the darkness in her chapter (with an assist from Gerald May) by way of the sad yet fascinating story of the persecution of Carmelite reformers, Teresa of Avila and her friend, John of the Cross, and the rich, mystical writing that emerged from those jail cells. Her insights drawn from being a hospital chaplain, learning to deal with hard emotions are good, if not novel, but the writing will bring you to your knees. My, my.

Although I could write more about this, I want to offer one aside: Barbara wisely and helpfully exposes the way in which much popular Christian theology is stuck in the dualisms that we often critique here — body vs soul, secular vs sacred, nature vs grace, higher vs lower, creation vs redemption, and the like. She herself wrote eloquently about this even in her first book, The Preaching Life, and it has been a major theme of her last two. For her to now suggest that many are driven from faith, and she herself from the traditional parish ministry, in part because this dualism is such a part of the orthodox Christian orientation — when she herself has shown that it is not proper to think in these split-level, ways — is a little odd. The critique she makes is fairly common among evangelicals and I can list a dozen books and blogs largely based on a rejection of Platonic dualism — think of old Francis Schaeffer, say, or Al Wolter’s Creation

Regained. Indeed, many with wholistic vision reject mysticism for this very reason, thinking it presumes too much nearly gnostic other-worldliness and a disembodied view of the human person. Why hasn’t her broad vision — certainly celebrated in other books — given her more resources sooner to embrace a reasonable and fruitful view of darkness and doubt? Certainly she isn’t really new to these questions, let alone the first to grapple with this stuff, even if she brings a colorful and good spin to it all. I don’t mean to dampen anyone’s enthusiasm for her good contribution — that should be clear — and I wouldn’t accuse such a lovely person as she as being disingenuous. But there ya go: she herself has been a good voice in creation-honoring, human-affirming, honest, incarnational faith, that allows questions and struggles and doubts and darkness, even, for decades, actually, and the caricatures of overly happy “solar” faith seems somehow maybe a bit of a foil. Or a marketing schtick. Could it be? Nonetheless, the book is good, even if I want to say–oh yes, many of us have been saying this, and she herself has been saying it, for years. Thank goodness it is being said so nicely, once again.

Her closing epilogue, “Blessing the Day” starts with Psalm 19:2. I’ve preached on this text myself — I learned to love it from the opening sermon in Calvin Seerveld’s book on aesthetics, Rainbows for the Fallen World. But I must say I’ve never noticed the bit about night. It is a good last chapter, even though I myself am a little anxious about sharing it with you — not because grappling with the dark is dangerous, or that lunar style faith that waxes and wanes is bad, but because she tends to minimizes Christian certainties. I do not want to derail anyone’s healthy confident faith, and I know some strict critics will shame me for promoting an ambiguous theologian who they fear is on a very slippery slope.

Well. Read this, and see if it is for you or someone you know:

The reasons that I had been given for staying out of the dark were becoming less and less convincing as I had more and more occasions to walk in it – caring for aging parents, going to funerals of people I loved, coping with economic crisis, seeing ice caps melt and watching churches close – all the while weighing a bag of Christian certainties that had less in it all the time. The energy required to keep darkness at bay was fast becoming more than I could manage. Perhaps there was another way?

Rev. Taylor is critical of those who insist that Christian faith is always about living in the light — “full solar spirituality” she calls it, and she means more than merely the wacky “name it and claim it” prosperity folk or the ever smiling Joel Osteen types — and she worries about using faith to bypass the hard stuff. “This full solar version of Christianity works so well for so many people that those of us who cannot buy it are bound to wonder what is wrong with us. I wondered what was wrong with me, anyhow, which was why I needed to know more about darkness.”

The best thing I can say is that learning to walk in the dark has allowed me to take back my faith, removing it from the glare of the full solar tradition to recover by the light of the moon. Now the sun still comes up, but is also goes down. Blessing the day means accepting my full quota of light and dark, even when I cannot see what I am blessing. Is this dangerous? Perhaps. At this point I am more afraid of what I might leave out instead of what I might let in. With limited time left on this earth, I want more than the top halves of things – the spirit but not the flesh, the presence but not the absence, the faith but not the doubt. This late in life I want it all.

Among the other treasures of darkness I have dug up along the way are a new collection of Bible stories that all happen after dark, a new set of teachers who know their way around the dark, a deeper reverence for the cloud of unknowing, a greater ability to abide in God’s absence and – by far the most valuable of all – a fresh baptism in the truth that loss is the way of life. That last one is hard to trust, which is why I need to keep walking in the dark. It takes practice to keep stepping into la noche oscura, to keep seizing the night as well as the day. My hope is that when the last big step comes, both my legs and heart will know the way.

In the meantime, I am planning a moon garden in the open patch outside my kitchen window, to go with the day lilies that crowd the driveway from late spring through autumn. Moon gardens have been around a long time, though most people who plant them nowadays supplement the moonlight with cleverly hidden artificial lights that do not wax or wane. The light in my garden will wax and wane.

In a passage just a bit too long to quote here (but perfect on the last page of the book) she lists the flowers and plants she’ll plant, and why. It’s really nice.

And then she says,

The names are so lovely that I may just say them over and over again instead of punishing my knees with the actual planting of a garden. Then again, what better way to keep track of what phase the moon I in than to watch the light in my garden grow? And what better way – when the moon and the flowers are both full, and I go outside to walk among them – to remember how much light there is in the dark.

You can order this beautiful book from the Hearts & Minds website by clicking on the order form tab below. Or, you can ask questions by clicking on the inquiry tab. But first, consider these good books that came to mind to supplement Taylor’s book. We have them all on sale, of course. Enjoy!

If you still aren’t sure, listen to or watch this wonderous lecture, given at the Rothko Chapel in Houston, which includes direct passages from the book, Learning to Walk in the Dark.

SIX OTHER BOOKS THAT MIGHT INTEREST YOU

H ome Behind the Sun: Connect with God in the Brilliance of the Everyday Timothy Willard & Jason Locy (Nelson) $19.99 This may be counter-intuitive or seem as if I’m hedging my bets, offering a book about light and brilliance beside a book on darkness. Yet, this is not cheap grace or a cover-up of the scary stuff, it is about finding the glory of the mundane, the presence of God in the midst of the daily. These guys are poets and passionate writers, citing Yeats and Blake and John Muir and Flannery O’Connor. They ought to cite BBT, too, as this is a bit like her remarkable An Altar in the World. It is about purpose and joy and healing and hope, naming our brokenness and hurts, but also looking for signals of transcendence in the ups and downs of a life intentionally lived for God’s glory. This is creatively written, powerful, poetic, and includes a study guide to help guide good discussions about its offer for a deeper, more brilliant awareness of God’s holy presence in all things.

ome Behind the Sun: Connect with God in the Brilliance of the Everyday Timothy Willard & Jason Locy (Nelson) $19.99 This may be counter-intuitive or seem as if I’m hedging my bets, offering a book about light and brilliance beside a book on darkness. Yet, this is not cheap grace or a cover-up of the scary stuff, it is about finding the glory of the mundane, the presence of God in the midst of the daily. These guys are poets and passionate writers, citing Yeats and Blake and John Muir and Flannery O’Connor. They ought to cite BBT, too, as this is a bit like her remarkable An Altar in the World. It is about purpose and joy and healing and hope, naming our brokenness and hurts, but also looking for signals of transcendence in the ups and downs of a life intentionally lived for God’s glory. This is creatively written, powerful, poetic, and includes a study guide to help guide good discussions about its offer for a deeper, more brilliant awareness of God’s holy presence in all things.

Jonathan Merritt writes, “Home Behind the Sun is so elegant and moving that it nearly took my breath away. The prose glimmers and rattles and nearly every page forced me to wrestle with important questions about joy, whimsy, imagination, and purpose. Home Behind the Sun is a poetic portrait of God’s glory that is as brave as it is beautiful. As you read it, breath deeply.”

It isn’t of the same tone or theological leanings of Ms. Taylor, but it is a good companion volume, moving and exciting, rooted in the grand story of God’s redemptive work in the world, and our truest identity as children of God.

E choes of a Voice: We Are Not Alone James W. Sire (Cascade Books) $29.00 For years and years many of us have looked to James Sire as a guide to apologetics, worldview studies, Christian philosophy. He was an influential editor at InterVarsity Press (influenced by and introducing the wider world to the early work of Francis Schaeffer.) Sire is a gentleman, a real scholar, widely read, and allowed me years ago to help with a bibliography he updated from The Transforming Vision in his own Habits of the Mind: Intellectual Life as a Christian Calling. This is about his own experience on the rim of the Nebraska sandhills, and how he came to conclude that ordinary life – and extraordinary emotions drawn from attentiveness to real life — points to a higher power. Is there meaning in these unbidden and strange experiences? What are the signals of something Other? He brings his logic and philosophical training to bear on finding the meaning in experiences that all of us have encounters, and how we interpret things, exploring our deepest longings.

choes of a Voice: We Are Not Alone James W. Sire (Cascade Books) $29.00 For years and years many of us have looked to James Sire as a guide to apologetics, worldview studies, Christian philosophy. He was an influential editor at InterVarsity Press (influenced by and introducing the wider world to the early work of Francis Schaeffer.) Sire is a gentleman, a real scholar, widely read, and allowed me years ago to help with a bibliography he updated from The Transforming Vision in his own Habits of the Mind: Intellectual Life as a Christian Calling. This is about his own experience on the rim of the Nebraska sandhills, and how he came to conclude that ordinary life – and extraordinary emotions drawn from attentiveness to real life — points to a higher power. Is there meaning in these unbidden and strange experiences? What are the signals of something Other? He brings his logic and philosophical training to bear on finding the meaning in experiences that all of us have encounters, and how we interpret things, exploring our deepest longings.

Here is how his long-time friend Os Guinness explains the significance of this important new book:

“For dwellers in our modern ‘world without windows’ or for prisoners in Plato’s cave content with the flickering shadows on the wall, Sire has given us a brilliant and helpful survey of pathways to the sun and freedom – some sure and some illusory. Echoes of a Voice should be read by all who wrestle with communicating faith persuasively today.“

Y earning for More: What Our Longings Tell Us About God and Ourselves Barry Morrow (IVP) $15.00 This book is similar in theme to the thoughtful one by Sire, above, but it is more beautifully written, a less autobiographical, and a bit more broad. I cannot say enough good about it. As John Wilkinson, author of the provocative No Argument for God puts it, “Yearning for More uncovers the reality of God in the most unexpected places. Barry Morrow cleverly identifies ‘signals of transcendence’ in our hatred of death, our desire for heaven, and even the humdrum of daily living. So often we are told to ‘go with your gut.” Morrow takes this to a whole new level.” Another rave endorsement comes from the always reliable Kenneth Boa. As Boa puts it, “my friend Barry Morrow has a penchant for leveraging culture to illuminate timeless spiritual issue.” Yes, indeed, this puts him in similar territory as great saints of the past, as he explores touchstones or reality in our work and play, our desires and alienations, our leisure and joys, and yes, our dark nights of the soul. Very highly recommended.

earning for More: What Our Longings Tell Us About God and Ourselves Barry Morrow (IVP) $15.00 This book is similar in theme to the thoughtful one by Sire, above, but it is more beautifully written, a less autobiographical, and a bit more broad. I cannot say enough good about it. As John Wilkinson, author of the provocative No Argument for God puts it, “Yearning for More uncovers the reality of God in the most unexpected places. Barry Morrow cleverly identifies ‘signals of transcendence’ in our hatred of death, our desire for heaven, and even the humdrum of daily living. So often we are told to ‘go with your gut.” Morrow takes this to a whole new level.” Another rave endorsement comes from the always reliable Kenneth Boa. As Boa puts it, “my friend Barry Morrow has a penchant for leveraging culture to illuminate timeless spiritual issue.” Yes, indeed, this puts him in similar territory as great saints of the past, as he explores touchstones or reality in our work and play, our desires and alienations, our leisure and joys, and yes, our dark nights of the soul. Very highly recommended.

T he End of Our Exploring: A Book About Questioning and the Confidence of Faith Matthew Lee Anderson (Moody Press) $13.99 This small paperback has more value than some books twice the size or price – it is splendidly written, very moving, a fine example of younger evangelicals and new kind of invitation to think deeply and faithfully. Do we know what it even means to “question well’? Anderson (whose book about the body called Earthen Vessels is very good) insists that “we need not fear questions, but by the grace of God, we have the security to rush headlong into them and find ourselves better for it on the other side.”

he End of Our Exploring: A Book About Questioning and the Confidence of Faith Matthew Lee Anderson (Moody Press) $13.99 This small paperback has more value than some books twice the size or price – it is splendidly written, very moving, a fine example of younger evangelicals and new kind of invitation to think deeply and faithfully. Do we know what it even means to “question well’? Anderson (whose book about the body called Earthen Vessels is very good) insists that “we need not fear questions, but by the grace of God, we have the security to rush headlong into them and find ourselves better for it on the other side.”

I am not sure why I wanted to share this little book, now. Barbara Brown Taylor’s memoir is a call to question, and call to embrace ambiguities, to walk in the dark. As I’ve said, I think this is a very good thing, and she is helpful to guide is into hard stuff. Yet, I also want to commend a solid and helpful book like this which reminds us that “faith helps us see, and that means not shrinking from the ambiguities and the difficulties that provoke our most profound questions” and yet also that “we must learn to question well.” We are called to walk worthy of the calling of Christ. Matthew lives now in Oxford where he is studying for an M.Phil in Christian ethics. Sharp, thoughtful, nice.

S eeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully: The Power of Poetic Effort in the Work of George Herbert, George Whitefield, and C.S. Lewis John Piper (Crossway) $19.99 For those who know the fiery, dogmatic, Puritan preacher who has given his life to “the supremacy of Christ in all things” and a passion for advancing the idea that we can take joyful delight in making much of God, it might seem at first incongruous — some might say unthinkable — to put Piper and Taylor on the same list. But yet. This is the latest installation of his fine “Swans Are Not Silent” series, the series which takes up the line from Augustine’s successor, who in 426 AD was so overwhelmed that the eloquent bishop and great thinker was would fall silent. No, great voices from great lives of the past remain vital, and in this series, Piper gives three short biographies in each volume (each around a theme, such as perseverance or coping with suffering or preaching well about sovereign grace.) This one, as the subtitle notes, is about the very thing with which I started the Barbara Brown Taylor review — how to combine beauty and truth, writing that is at once creative and artful and helpful and good.

eeing Beauty and Saying Beautifully: The Power of Poetic Effort in the Work of George Herbert, George Whitefield, and C.S. Lewis John Piper (Crossway) $19.99 For those who know the fiery, dogmatic, Puritan preacher who has given his life to “the supremacy of Christ in all things” and a passion for advancing the idea that we can take joyful delight in making much of God, it might seem at first incongruous — some might say unthinkable — to put Piper and Taylor on the same list. But yet. This is the latest installation of his fine “Swans Are Not Silent” series, the series which takes up the line from Augustine’s successor, who in 426 AD was so overwhelmed that the eloquent bishop and great thinker was would fall silent. No, great voices from great lives of the past remain vital, and in this series, Piper gives three short biographies in each volume (each around a theme, such as perseverance or coping with suffering or preaching well about sovereign grace.) This one, as the subtitle notes, is about the very thing with which I started the Barbara Brown Taylor review — how to combine beauty and truth, writing that is at once creative and artful and helpful and good.

Piper would no doubt disagree that some of Barbara’s more liberal ideas are truly true, but nonetheless, this volume is brilliant. We learn about the great English poet, the eloquent and gifted oratory, and the uniquely talented novelist and apologist. Yes, in these three wonderful chapters we learn about the beauty of poetry and “the relationship between poetic effort, on the one hand, and perceiving, relishing, and portraying truth and beauty, on the other hand — especially the truth and beauty of God in Christ. The three men in this book made poetic effort to see and savor and show the glories of Christ.” Piper observes that the three were each Anglicans — a pastor-poet, a preacher-dramatist, and a scholar-novelist. Pastor Piper, who has studied the rich theories of beauty in Jonathan Edwards and in C.S. Lewis (just for instance) says his thesis is simple: “the effort to say beautifully is, perhaps surprisingly, a way of seeing and savoring beauty.” I might add, “even in the dark.”

M aking Manifest: On Faith, Creativity, and the Kingdom at Hand Dave Harrity (Seedbed Publishing) $16.95 I have been wanting to mention this very special book once again, and this is the perfect time — it is a gem of a guidebook for exploring well the stuff of of our real lives, including nature, experiencing God by using our own senses, our attentiveness, our creative ruminations, our own love of words. This is a well-crafted handbook for meditative writing, using words well, and allowing our own sense of poetry to point us to deeper awareness of our own lives, and of God. As Brett Foster, Professor of Creative Writing at Wheaton College says, “Rarely have I encountered a writer and teacher of writing who thinks so highly of poetry’s potential to give voice to our lives… in such a persuasive, inspiring way.”

aking Manifest: On Faith, Creativity, and the Kingdom at Hand Dave Harrity (Seedbed Publishing) $16.95 I have been wanting to mention this very special book once again, and this is the perfect time — it is a gem of a guidebook for exploring well the stuff of of our real lives, including nature, experiencing God by using our own senses, our attentiveness, our creative ruminations, our own love of words. This is a well-crafted handbook for meditative writing, using words well, and allowing our own sense of poetry to point us to deeper awareness of our own lives, and of God. As Brett Foster, Professor of Creative Writing at Wheaton College says, “Rarely have I encountered a writer and teacher of writing who thinks so highly of poetry’s potential to give voice to our lives… in such a persuasive, inspiring way.”

If you like Barbara Brown Taylor, if you are inspired by her artful writing — or her invitation to face the nightimes of our lives — I think this workbook on paying attention, making manifest God’s reign through sacred writing and learning to craft your own true lines could be very, very useful.

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333