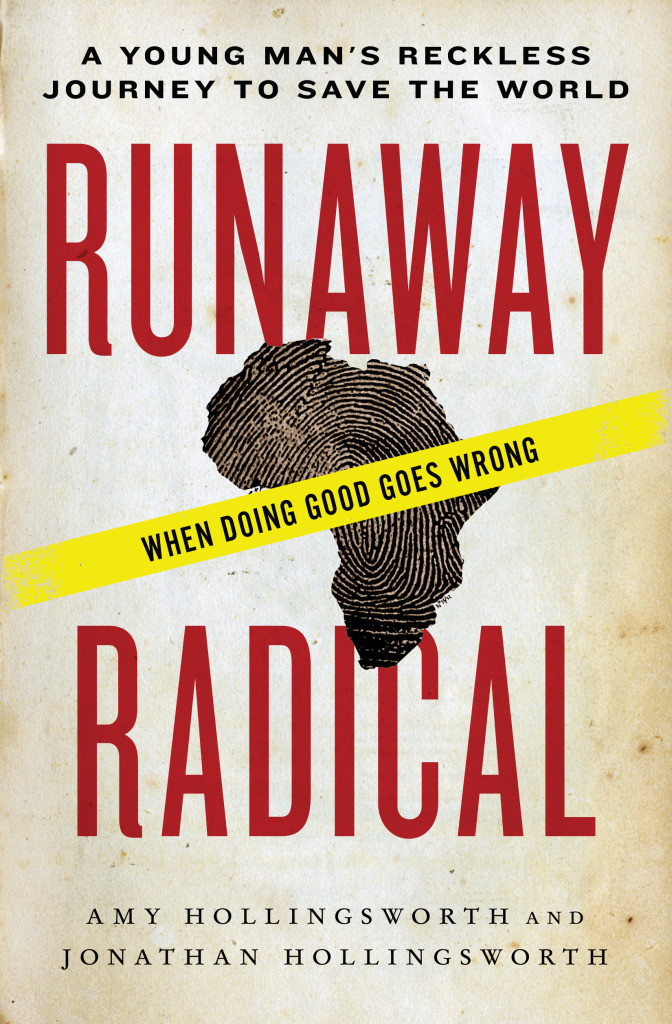

Runaway Radical: A Young Man’s Reckless Journey to Save the World by Amy Hollingsworth and Jonathan Hollingsworth (Thomas Nelson – regularly $15.99) is a book that is very well written, exceptionally moving, of interest to many different sorts of readers, and, I think, is very, very important. I could hardly put it down, except when I had to stop to talk to Beth about it. (And boy, did it cause me to ponder, to pray, to confess, even. It struck fairly close to home, for some reasons I need not describe here.) I think it is the best book I’ve read so far this year.

Hollingsworth and Jonathan Hollingsworth (Thomas Nelson – regularly $15.99) is a book that is very well written, exceptionally moving, of interest to many different sorts of readers, and, I think, is very, very important. I could hardly put it down, except when I had to stop to talk to Beth about it. (And boy, did it cause me to ponder, to pray, to confess, even. It struck fairly close to home, for some reasons I need not describe here.) I think it is the best book I’ve read so far this year.

RR is a quick read, although one will want to ponder it, maybe talk with others about it. It is a book worth having, worth sharing. I want to describe it to you, dear H&M friends, as it is a fascinating story, co-written by a mother and her son, (itself a winning combination in this case as both are good writers, characters I’ve come to care about.) And both have a story to tell; do they ever! It’s a mother watching her son, and her son’s own recollections as his life goes haywire. The slogan on the cover shouts, “When Doing Good Goes Wrong.” Wow.

Of course, you can order this at our 20% off discount by clicking on the order form below, which takes you to our website’s secure order form page. I think that many BookNotes readers will be drawn to this wise and poignant book as the concerns it raises are, as we say, on your radar screen. I know they are very much on ours.

The subtitle gives a hint of what is to come: the young man, Jonathan, is drawn to a radical sort of missional faith, and is eager to show the world what genuine Christian compassion looks like. He has read books, attended conferences, come to realize that bland and ordinary faith pales in comparison to a lively, sacrificial, culturally-engaged discipleship, and that the fruit of such a radical vision is seen in serious acts of selflessness and caring outreach, showing love to the loveless, tending the wounds of the broken, befriending the homeless, serving the poor.

A youthful mission trip to Central America leaves him stunned, wanting to do more long term work to alleviate brutal poverty. He deepened his passion for such things, inspired by the likes of our friend Shane Claiborne who a few years ago was particularly known for calling on young evangelicals to give away their wealth and live among the poor, or the titular Radical: Taking Back Your Faith from the American Dream (David Platt) that pushed theologically conservative young adults to renounce the idols of the status and wealth and normalcy and give their lives to missionary service. Jonathan deepened his friendship with the local poor, gave even college money away, shaved his head as a sign of renunciation, and started a rigorous process of meditating on quotes from recent books — sources that some might call “radical Christianity” or new monasticism, perhaps.

Runaway Radical, you might surmise, doesn’t end well and you wouldn’t be far off in that judgment.

Although, actually, it ends beautifully — the eloquent, wise, painful and joyful last chapters are to be savored, maybe through tears; the Epilogue (“Saving the World”) is worth the price of the whole book. Jonathan is no longer the self assured, (arrogant?) evangelical solider with zeal and confrontational, hard truths, but humble, sobered, a bit tentative, even, with the tone, perhaps, of reoriented Hebrew faith after the exile — restored, yes, joyful, even, but a lot wiser for the wear.

To get to the end of this story, and to share this new found comfort being in a place of some woundedness and with no easy answers in sight, other then the confidence in God’s great mercy, one has to go through some exceptional weirdness and some very sorry stuff. His own interior life is transformed (not to mention those of his parents) as his missionary experience goes very wrong, he is abused by a toxic home church, his faith and much of his worldview dashed. The book unfolds wonderfully, bringing together these themes and chapters of his downward spiral, from his mother’s point of view and then in his own recounting. There are poignant and revealing journal entries and some lovely memoir – Amy recalling stories of Jonathan’s childhood, prayers the parents prayed for their children, questions he asked them as a child, the faith journey of Jonathan in high-school and his first year of college before he left to serve in Africa. Much of this will sound familiar to anyone who has watched the faith development of serious young Christians these days.

Amy, as the mother of this boy who grows increasingly religiously obsessed, is an excellent writer (and no stranger to the evangelical publishing world) and pours out her admiration and concern for her son. She sees the red flags, she notices some peculiar traits, but she also knows that great missionaries or social reformers of the past have appeared critical of a church or culture given to trivial pleasures or cultural accommodation or American nationalism. It is hard to argue when your son is writing quotes from the church fathers or Mother Theresa, Martin Luther King or heroic world missionaries on his bulletin board. Her telling of her own navigating all of Jonathan’s changes is itself part of the brilliance of this story and not to be missed. Any parent concerned about their children, I think, will resonate with much of this, and be glad for her pleasant memories and her shocking revelations.

The family’s faith seems to be a bit charismatic and they are part of a lively evangelical subculture, eager to follow the promptings of the Spirit. Despite the warning signs and the rather judgmental attitude their son develops, they are supportive. (How could they not be: she recounts wonderful memories of Jonathan’s tender conscience as a child; they have been attentive to his dreams, both his passions and interests, and the literal sort. More than once, Amy recalls and dissects haunting dreams with profound self-awareness.) There were moments in her narration that I was struck by what a good parent she seemed to be. She and her husband, despite Jonathan’s furious foray into a radical movement that proved to be unhealthy, can serve as good role models for how parents of young adults can accompany their adult children, and I commend the book for this reason, too.

For instance, she tell us,

One Sunday morning before church I began to pray for him. The kind of praying that starts out very noisy, then the words fail and trail off and you end up mostly listening. And what I heard was that my husband and I were to pray about whether Jonathan should take a year off school to serve overseas. Of course I didn’t remember at the time that Jonathan had predicted this, had asked for it two years before when he started college. A lot had happened between then and now, including the false starts and missteps. At the moment it wasn’t in Jonathan’s plans; he was filling out applications to transfer to a new college in the fall. I told my husband right away what I had heard in prayer, asking him to hold the arguments against the gap year until we had more time to talk about it. I had the same concerns. Leaving college midway doesn’t always end well. There was a real chance he wouldn’t finish his education. And the timing on previous attempts to go had always been off.

A few minutes later Jonathan came down for breakfast and he and Jeff were alone in the kitchen together. “Are you excited about starting a new college in the fall?” my husband asked. “No,” Jonathan answered. “I really think I’m supposed to take a year off to serve instead.”

In a paragraph on the next page she writes a simple observation that nearly brings me to tears as I re-read it now:

Then the whirlwind began. Inquiries were made, and the first agency he asked accepted him. The money was raised in six weeks. Every detail fell into place. It was the first of many milestones, the first of many lessons. It was also the year we learned the cruelest of paradoxes, that a young man can be both called and led astray.

I want to say a few things about this book, and the matters it raises, and we invite you to order it so you can see for yourself the beauty of the writing, the honesty of the narrative, and the significance of this conversation.

First, the way in which Jonathan became obsessed with his own wealth, his own need to show himself to be more literally committed to Christ’s ways, and his passion to make a difference in the world became harsh and twisted, and this distorted approach is discussed with raw integrity and much candor. As he tells it, he realizes now that he was stuck in a view that was “the antithesis of grace” and missed the truth that Christ came “to liberate us from the need to be radical.” I am not sure why he took to books like Radical and Crazy Love and The Irresistible Revolution, and then read them in such a legalistic and graceless manner, but he did. “If it was legalism that shut me out,” he finally writes near the end, “it was grace that snuck me in.” In many ways, this is the heart of the book — what some call “works righteousness” versus free grace. It is vital and sweet stuff, lessons hard learned, important for suburban moms and conventional, older pastors as well as culturally savvy and radically committed young adults.

This is not the first book, by the way, that has named some of the problems of what may be a “new legalism” (as Anthony Bradley has called it) and the apparent disdain among many popular authors and leaders to an “ordinary” kind of faith. This is directly discussed in the new book by Michael Horton called Ordinary: Sustainable Faith in a Radical, Restless World (Zondervan; $15.99.) We have promoted here more than once the lovely little book called The God of the Mundane: Reflections on Ordinary Life for Ordinary People by Matthew Redmond (Kalos Press; $10.95) which anticipated some of these recent concerns and, to be honest, it is why I did the column a few weeks back on books that celebrate the common pleasures of life in God’s

This is not the first book, by the way, that has named some of the problems of what may be a “new legalism” (as Anthony Bradley has called it) and the apparent disdain among many popular authors and leaders to an “ordinary” kind of faith. This is directly discussed in the new book by Michael Horton called Ordinary: Sustainable Faith in a Radical, Restless World (Zondervan; $15.99.) We have promoted here more than once the lovely little book called The God of the Mundane: Reflections on Ordinary Life for Ordinary People by Matthew Redmond (Kalos Press; $10.95) which anticipated some of these recent concerns and, to be honest, it is why I did the column a few weeks back on books that celebrate the common pleasures of life in God’s good creation, with titles such as Becoming Worldly Saints: Can You Serve Jesus and Still Enjoy Your Life? a must-read book by Michael Wittmer (Zondervan; $15.99.)

good creation, with titles such as Becoming Worldly Saints: Can You Serve Jesus and Still Enjoy Your Life? a must-read book by Michael Wittmer (Zondervan; $15.99.)

I could (and perhaps should) write much more about this, but I shall say this much for now: even though some have misinterpreted the call to resist the idols of our American culture and the need to serve and distorted it into a new more-radical-than-thou form of self-righteousness or a new kind of gruff legalism, we should not blame the call to fight poverty, to love the unlovable, to forge a church that is missional and outward focused, or those who offer those calls, for how some may misapply the challenge. Perhaps the call to the cost of discipleship in our time isn’t being given with enough joy and grace, making it easier for some listeners to turn it in unhealthy or self-destructive directions or to disturbing extremes. Still, we shouldn’t throw the baby out with the bathwater, here.

We don’t typically blame authors who call us to pray and stop promoting books about prayer when some oddballs start peculiar practices that turn intimacy with God into weird mysticisms. We don’t stop hoping for fruitful evangelism even though some are pushy and rude, and we still promote the best books on the subject, perhaps even more so, to counter the negative practices; we don’t quit searching for healthy and wholesome sexuality because some have turned to nasty negativity or liberal license. In each case, the possibility of somebody taking good books and twisting them into attitudes or lifestyles that are not intended by the authors shouldn’t keep us from pushing those ideas. Like anything, good ideas can be warped and lived out in unhealthy imbalance.

In other words, there is a lot of discussion we need to have, especially around this question of how countercultural our faith should be and in what contexts radical lifestyles should be pursued and in what ways a wise group of discerning friends in a local faith community can help us remain winsome and healthy even as we commit to serious sacrifices. Those of us who promote these sorts of books and invite people to more dedicated sorts of discipleship, especially around social concerns, need to be thinking about this, and we need to be talking about the possibility that we may be liable for leading impressionable younger adults astray if we don’t offer them a solid, grace-filled and healthy foundation out of which they can make life-transforming decisions. This book gives us a lot to ponder, so I commend it especially to those who work with younger adults, youth and campus ministers, and anyone involved in developing social activists or missionaries.

Such urgent conversations could be stimulated by Runaway Radical even though it isn’t the task of this memoir to give us a healthy and balanced and Biblically-wise view of how to go about joining the fight for a better world or what to think, theologically and practically, about stuff like John Perkins calling us to “relocate” or John Piper saying “risk is good” or Ron Sider calling us to a more simple lifestyle, inspired by the Bible’s demand for charity and justice. (I loudly praise God for Ron Sider and his Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger book, by the way, and will happily celebrate yet another new edition this summer. He is a mentor and model of a balanced, fair-minded approach to these matters.)

We dare not throw under the bus the jovial gadfly Shane Claiborne, The Simple Way and the new monastic movement, or activist authors like pastor Eugene Cho (Overrated), Chris Heuertz (Friendships at the Margins and Unexpected Gifts) Jeff Shinabarger (More or Less: Choosing a Lifestyle of Excessive Generosity,) Scott Bessenecker (The New Friars and Living Mission), Christine Caine (Undaunted and Unstoppable), Jeremy Courtney (Preemptive Love), Ken Wystma (Pursuing Justice: The Call to Live and Die for Greater Things) or the good folks at Mission Year, say, inviting young adults to a year of voluntary service where they can see, as their latest, wonderful book puts it, God is in the City: Encounters of Grace and Transformation (by Shawn Casselberry.) Who would ever want to silence the always whimsical, Jesus-centered, if sometimes audacious Bob Goff, author of the popular Love Does? I’m glad for extraordinary DVD curriculum like the World Vision produced Start. Or the compelling book by their director, Richard Stearns, The Hole in the Gospel. And glad for the publicity given in recent years to those who fight sexual trafficking through groups like A21, The International Justice Mission (IJM) or Not for Sale.

Mission), Christine Caine (Undaunted and Unstoppable), Jeremy Courtney (Preemptive Love), Ken Wystma (Pursuing Justice: The Call to Live and Die for Greater Things) or the good folks at Mission Year, say, inviting young adults to a year of voluntary service where they can see, as their latest, wonderful book puts it, God is in the City: Encounters of Grace and Transformation (by Shawn Casselberry.) Who would ever want to silence the always whimsical, Jesus-centered, if sometimes audacious Bob Goff, author of the popular Love Does? I’m glad for extraordinary DVD curriculum like the World Vision produced Start. Or the compelling book by their director, Richard Stearns, The Hole in the Gospel. And glad for the publicity given in recent years to those who fight sexual trafficking through groups like A21, The International Justice Mission (IJM) or Not for Sale.

Runaway Radical: A Young Man’s Reckless Journey… does not suggest that any of these authors or organizations knowingly misguided anyone, and I do not mean to imply that the Hollingsworths have given up on making a difference in this sad world, or blame any particular book or author for seducing Jonathan into his misguided Africa trip. But some readers might, so I say, again, that we shouldn’t throw these prophets in our midst under the bus. For my own part, I had to ask myself tough questions, since we have so promoted these exact kind of books, and have been eager to see these sorts of young voices picking up the causes of global justice. In my own years of campus ministry decades ago, I had these very kinds of conversations and figuring how to be grace-filled and balanced and sustained by Christ-like virtues as we engage the powers has been a long-standing concern of mine.

(I recall reading in the 70s something by John Stott about being a “conservative radical.” I love a book that we still stock by Ron Sider called I Am Not A Social Activist which is about keeping Jesus at the heart of our efforts for social transformation. There is no new legalism in these kinds of works, but many of us have struggled hard to keep this all in balance. It is in some respects, the heart of Steve Garber’s Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, that asks how we can love the broken world God so loves without growing bitter, jaded, cynical. Oh how I wish I could have pressed these into the hands of Jonathan years ago… and oh, how I will press the Hollingsworth’s RR book into the hands of the latest generation of young radicals.)

Recently, interestingly enough, I was interviewed by a reporter for a trade journal for the publishing industry, asking about changes we’ve seen in our 33 years of book-selling. One of the top changes on my list? Evangelicals robust and thoughtful and characteristically energetic embrace of the Biblical call for peace and justice, racial reconciliation and creation-care, grounded in a consistent ethic of life. What Sojourners and Evangelicals for Social Action were crying out about 40 years ago is now commonplace among most young evangelicals, and this is surely one of the most interesting sociological phenomenon of our lifetime. We should be very glad for this trend, a faithful move of young authors and leaders calling us to care, to take up serious work, and to be more involved than we often are in the call to help heal the broken, hurting world. I am glad for events like The Justice Conference or the sophisticated Urbana world missions conference and even the risky Christian Peacemaker Teams who are giving folks options for social involvement. (I am even more glad for the way our beloved Jubilee conference raises up equal passion for daily jobs and vocations in the marketplace and the arts, one of the great contributions they make to the feisty project of tapping fruitfully and wisely into youthful idealism and desire to “change the world.”)

So, to be clear: I am glad for these recent books about changing the world, serving the poor, working for social justice and such, even if our dear Jonathan recklessly misread or misapplied some of their challenging invitations. And we should, as perhaps Jonathan didn’t (the book’s greatest weakness is that it does not say) have wise friends around us, committed equally to social change, global justice, and balanced, beautiful, gracious, understandings of a mature interior life, that would help discern the ways in which we live into these big, big matters. I do not mean to digress to far afield, but this is why books that remind us of the communal and intimate nature of the local church are so important. Do you recall our discussion of Slow Church by Chris Smith and John Pattison last fall?

SPOILER ALERT

The self-destructive legalism and desire to prove to God that he was fully committed isn’t the only sad part of the story of Runaway Radical: A Young Man’s Reckless Journey to Save the World. A significant part of the story is a surprising twist in the plot: the mission agency in Cameroon where Jonathan goes is, to put it simply, corrupt. He sees abuse of funds, abuse of people — domestic violence and spiritual manipulation and emotional abuse. He cannot blow the whistle; he himself is seemingly caught in a nearly tragic situation. (Oh, the irony, that the Cameroon church leaders, all men, in that place, are preaching an extreme version of the false “prosperity gospel” and living large at the expense of their impoverished flocks. It is widely known that this troubling North American teaching has found significant inroads in many parts of the African church, and I was surprised that the Hollingsworth’s had apparently not adequately vetted this particular ministry or expected these sorts of troubles. How this mission agency was chosen is not explained although it becomes clear that it was connected to folks Jonathan knew, perhaps in the church in which he was involved. It is a slight hole in the narrative, but I suspect they are trying to be discreet and honorable. Throughout the book no names or authors or churches or ministries are named, which I suppose is to their credit.)

only sad part of the story of Runaway Radical: A Young Man’s Reckless Journey to Save the World. A significant part of the story is a surprising twist in the plot: the mission agency in Cameroon where Jonathan goes is, to put it simply, corrupt. He sees abuse of funds, abuse of people — domestic violence and spiritual manipulation and emotional abuse. He cannot blow the whistle; he himself is seemingly caught in a nearly tragic situation. (Oh, the irony, that the Cameroon church leaders, all men, in that place, are preaching an extreme version of the false “prosperity gospel” and living large at the expense of their impoverished flocks. It is widely known that this troubling North American teaching has found significant inroads in many parts of the African church, and I was surprised that the Hollingsworth’s had apparently not adequately vetted this particular ministry or expected these sorts of troubles. How this mission agency was chosen is not explained although it becomes clear that it was connected to folks Jonathan knew, perhaps in the church in which he was involved. It is a slight hole in the narrative, but I suspect they are trying to be discreet and honorable. Throughout the book no names or authors or churches or ministries are named, which I suppose is to their credit.)

The book has an active facebook page and Ms Hollingsworth has been writing a bit about the reception the book has gotten since its release just a few weeks ago. She is a lively and good writer, as I’ve said, and she is in communication with readers of all sorts. Not surprisingly, others have poured out their stories, she has said, telling their own tales of missionary service gone awry, mission agencies that have been abusive, and more. They are stories that need to be told.

There is a large shelf here at the bookstore of books of missionary biographies and autobiographies – some tell of evangelism and church planting, others talk of medical missions or social service efforts, and of course we have books about those who have started relief or development projects in the developing world. Some document the history of mainline denominational churches and their long-standing work (my friend Mark Englund-Krieger just released a history of Presbyterian (USA) missionary work called The Presbyterian Mission Enterprise: From Heathen to Partner) while others write of edgy, fresh projects, such as Kisses From Katie by Katie Davis which tells of her unusual solo journey to Uganda to adopt dozens of children or Preemptive Love by our friend Jeremy Courtney who is networking medical missionaries and others to perform life-saving pediatric surgeries in Iraq as they try to reform the complicated health care problems in a war torn, religiously conflicted land. A few tell about the great sacrifices and hardships endured, but end well. Or, maybe they don’t, and they are less sanguine then the success stories.

Few, though, so honestly share these kinds of stories of the really dark side of missions, the misappropriation of funds and the harsh treatment of incoming missionaries. Jonathan knew in his gut something was wrong when a building he was to work on was nonexistent, when the class he was to teach had just let out for the summer, when a large number of guitars that he had lovingly collected and personally shipped there for children were absconded for other uses. His hosts were strict bosses, even forbidding him to spend time at a nearby medical mission hospital as it was staffed by more mainline denominational Christians. Of course he wanted to be culturally sensitive to his new colleagues, submissive to their expectations of him, but he grew to believe that what they called “the African Way” was a crass justification for patriarchy and domestic violence. When they captured his visa and airline ticket home, he realized he was in some very deep trouble.

ANOTHER SPOILER ALERT

And so, the book continues — Jonathan telling of his experience in Cameroon, some of which is quite touching, occasionally delightful, even, while some becomes exceptionally disturbing. His mother shares her own memories of the sparse communications during those months, chapter by chapter they take turns, moving the narrative on.

And so, the book continues — Jonathan telling of his experience in Cameroon, some of which is quite touching, occasionally delightful, even, while some becomes exceptionally disturbing. His mother shares her own memories of the sparse communications during those months, chapter by chapter they take turns, moving the narrative on.

The story gets even more complicated and even uglier — oh my, can it possibly get worse? — when he arrives home to a toxic congregation, and strict orders from a head pastor to be utterly silent about the mistreatment of money and soul from the African mission leaders. The church was apparently committed to saving face and thought Jonathan was derelict for coming home prematurely, and did not appreciate at all he and his families concerns about misappropriation of money or the unbiblical, dangerous practices and dysfunction so prevalent at the mission compound. I needn’t explain it all here, but this harsh stuff back home in his Maryland sending congregation is demoralizing and infuriating. They tell the story well, and with a fair amount of grace and balance — I think other writers might have justifiably shown more bitterness. It is not a tell-all screed, but the manipulation and mistreatment back home is an important part of the story, and another contribution to the struggle about faith in this young man’s life. So they report it and at times it feels surreal. They bring you effectively into their world as only the best writers can.

This RR book, then, is about three big things — and a fourth.

First, it is about this radical movement of idealistic, costly discipleship which seems to be being understood by some as extreme, lacking in grace, a new Pharisee-ism. These books are being read by many young adults, inspiring some to a zealous and sacrificial dedication that is both exemplary and distressing. It is explored mostly not in the abstract as a theological movement, but as a set of influences that played havoc in the tender soul of this one young man. It is, after all, a memoir (in two voices) and you learn about Jonathan, less about the books and ideas and movement which informed him.

Secondly, Runaway Radical is about the experience of a missionary compound, staffed by indigenous folks in Cameroon, which was heterodox and dysfunctional at best, and toxic and dangerous at worst. Few mission stories speak of this down side, and it is as revealing as it is riveting.

Thirdly it is a bit about an unforgiving and manipulative church leadership team that did not offer support, let alone grace, to the troubled and hurting young man that came home broken from his failed missionary call. That some churches are grossly inadequate in welcoming home missionaries is known in the biz. That they would be manipulative and dishonest and threatening is tragic. This proved to be a “final straw” that broke dear Jonathan and outraged his parents, but they do not outline too much about this. If the book ended here it would be a very good book, honest and informative, enjoyable, if distressing. But it becomes a truly great book because of the final, fourth theme.

And it is this: heavy-handed, black and white thinking of the aggressive sort that guided the fiery young man’s faith left little room for doubt, let alone failure. Yet, in his journey into tough questions, a failed discernment of his call, and his experience of spiritual abuse at the hands of fundamentalists, he has emerged with a sober, gentle, and lighter sort of faith. He has not renounced the gospel, he has come to understand it more profoundly.

fiery young man’s faith left little room for doubt, let alone failure. Yet, in his journey into tough questions, a failed discernment of his call, and his experience of spiritual abuse at the hands of fundamentalists, he has emerged with a sober, gentle, and lighter sort of faith. He has not renounced the gospel, he has come to understand it more profoundly.

Some will applaud his new, tentative if grace-based faith, while others will fret that he has shifted towards a more ambiguous, less didactic and certain form of faith. He laughs more, now, it seems, and is healing. He is moving on. Neither mother or son seem cynical, even though they have reason to be. The book’s call to this more open-minded and grace-filled approach is beautifully rendered and the book ends well.

You will have to go along with the Hollingsworths on their journey, the ups and downs, and live the Paschal rhythm with them, I think, to see for yourself. Can this death of a previous faith be the fertile soil for new birth? Can a more sustainable faith rise out of the shell of the old? What is better, too much confidence or too little? Tight fists grasping onto truth or open hands? This is the old, old story, or so it seems to me — life from death, resurrection after crucifixion. Runaway Radical: A Young Mans Reckless Journey to Save the World is a great book to read in this Lenten season, and it is a revealing study of serious faith, serious global needs, serious misunderstandings and confusions, and serious, glad, if less ambitious, new understandings of faith, and renewed appreciation for grace. What a story, so well told!

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333