MY PREVIOUS POST ABOUT THE ARTS: IT’S GOOD FOR YOU

I hope you read our BookNotes post from earlier this week – there was a lot there. I gave several links to previous BookNotes lists of books about the arts, mentioned how Square Halo Books stood in for us at CIVA, selling our books at their Biennial arts conference in Grand Rapids, and I celebrated some of the authors who have been important in the conversation about faith, art, aesthetics, creativity and the like. From basic, introductory books like Art and the Bible by Francis Schaeffer, the very nice, if short, Art for God’s Sake: A Call to Recover the Arts by Philip Ryken or Michael Card’s call to creativity, Scribbling in the Sand: Christ and Creativity to larger, more demanding works by Calvin Seerveld, Nicholas Wolterstorff or Jeremy Begbie, we love promoting these remarkable books.

I am not an artist, obviously, and not very artful, except maybe in the way I am creative with the customs of grammar and normal speech, sometimes a master of malapropisms, but I really have been blessed to read these kinds of authors, to overhear these conversations about the relationship of faith and art. I often tell folks that Rainbows for the Fallen World by Calvin Seerveld (Toronto Tuppence Press; $30.00) is one of my favorite books of all time. There are many reasons why reading in this field is important, not the least of which is that we can all widen our understanding of the relationship of faith and life, worship and work, when we see others doing it in their own particular callings and vocations. To read about artists grappling with Christian theories of creativity or aesthetics or the history of their mediums inspires me to want to do that in my own vocation and career — think deeply and Biblically about the ideas and practices we embrace. Further, since we all are influenced by the arts – certainly by those in the popular arts, such as music, film, video games, TV – it is good for us to learn a bit about it. Being reminded of our being made in God’s image, and therefore natural-born storytellers, people who are creative, culture-makers (as the must-read Andy Crouch book Culture-Making puts it) in God’s good creation is valuable. Right? Such notions are life-transforming, for some.

Which is to say that even if you aren’t a cultural creative, can’t imagine yourself involved in arts ministry, and don’t care much about art history, these books, or at least some of them, are good for you.

Also, it is always our hope and prayer that these lists and bibliographies and the book reviews I do at BookNotes get, in God’s providence, into the hands of those who most need them. Maybe you can share yesterday’s column with others who might care, artists, patrons, art majors, art teachers, obviously, but also any church folks interested in these things.

A GREAT BOOK I COULDN’T PUT DOWN

On the heels of that ramble through past reviews, links to lists, and reviews of 10 recent books, I now want to tell you about just one book that I couldn’t put down. It is quite new, and I really, really enjoyed it, and I’m sure some BookNotes fans will get a kick out of it.

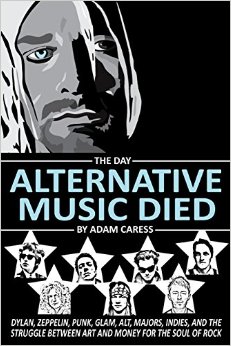

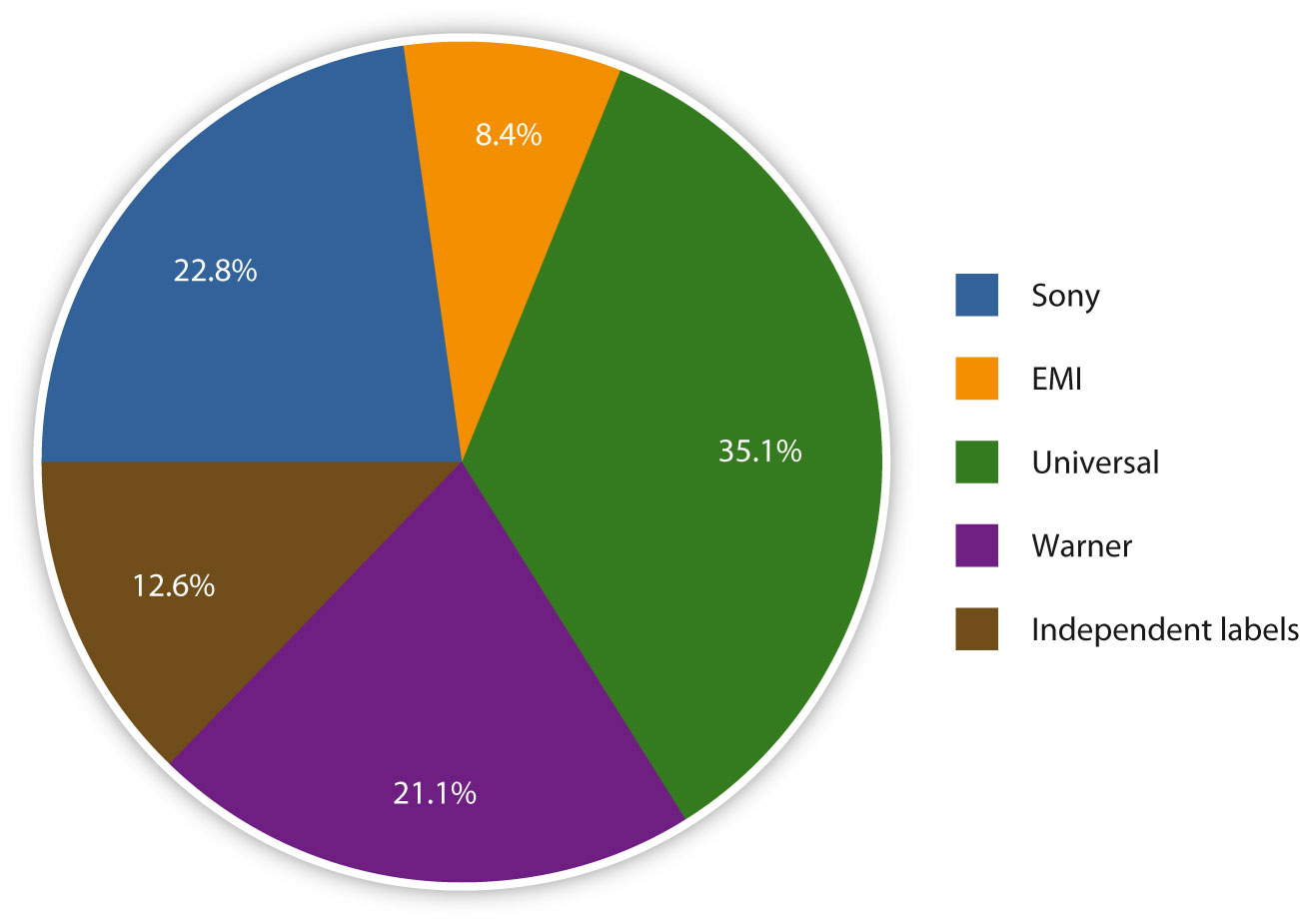

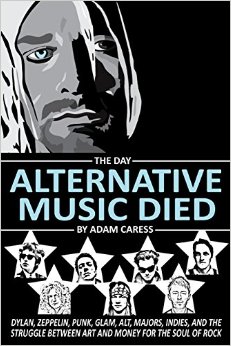

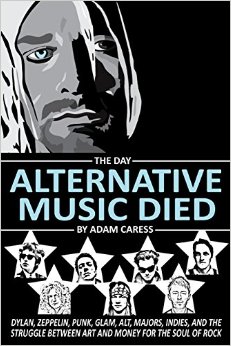

The Day Alternative Music Died: Dylan, Zeppelin, Punk, Glam, Alt, Majors, Indies, and the Struggle Between Art and Money for the Soul of Rock is wonderfully written by Adam Caress, published by indie outfit, New Troy Books ($16.99.) It covers a lot of ground, dipping into a variety of sociological themes and artistic questions, but is, mostly (as you can gather from the subtitle) about the tension between art and commerce in rock music, and, particularly, how the descriptor “alternative music” developed, was co-opted, nearly ruined, reinvigorated, and co-opted again, and how out of the rubble of the vast take-over of hundreds of artist-friendly record labels by commercially-driven, mega-corporations, a new sort of indie scene has developed.

The Day Alternative Music Died: Dylan, Zeppelin, Punk, Glam, Alt, Majors, Indies, and the Struggle Between Art and Money for the Soul of Rock is wonderfully written by Adam Caress, published by indie outfit, New Troy Books ($16.99.) It covers a lot of ground, dipping into a variety of sociological themes and artistic questions, but is, mostly (as you can gather from the subtitle) about the tension between art and commerce in rock music, and, particularly, how the descriptor “alternative music” developed, was co-opted, nearly ruined, reinvigorated, and co-opted again, and how out of the rubble of the vast take-over of hundreds of artist-friendly record labels by commercially-driven, mega-corporations, a new sort of indie scene has developed.

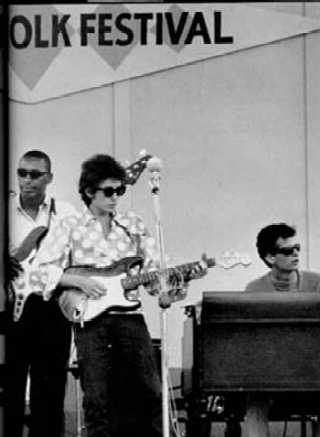

Much of this story starts when Dylan went electric. And he explains why in a brilliant set up in the first dozen or so pages.

NEW ROCK JOURNALISM: SERIOUS ART CRITICISM TO DUMB MYTHOLOGY

To make matters even more interesting, Caress shows how rock journalism rose in the late 1960s as a newly developing art form itself, as thoughtful and artistically informed writers like Lester Bangs, Robert Christgau, and Greil Marcus used classic critical methods – as one would in reviewing literature, theater, classical music, or jazz — believing that some rock musicians had something to say, and their medium was, indeed, a new art form. (The first issue of Crawdaddy! was ten pages long and included one long review of Simon & Garfunkle’s Sounds of Silence, written by a college student at Swarthmore; it was so impressive, Paul Simon called him in his dorm room to discuss it. Outlets like The Village Voice were doing serious evaluation of the profundity of rock music, creating a new community of a new kind of entertainment journalism and a new sophistication in popular music reviewing.)

Caress shows how, eventually, the premier outlet for such rock criticism, Rolling Stone, and later Spin, became tawdry and stupid, pushing a myth of “sex, drugs and rock and roll” to valorize materialism and fame. Caress is (rightfully) rough on these magazines and the eventual loss of serious rock criticism in their pages. For instance, he documents how early Rolling Stone reviewers savaged Houses of the Holy by Led Zeppelin (for its bad lyrics, routine song structures, unremarkable musicianship, curtailed passion, middling artfulness) but decades later, in their big-selling books of the best albums ever, gave them five-star, “must have” status.

He explains,

Throughout the 1990s Rolling Stone’s venerable influence helped legitimize a wholesale mythologizing of rock that was being actively cultivated by the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, a new spat of sycophantic “History of Rock and Roll” documentaries, and new myth-affirming TV franchises like VH1s Legends and Behind the Music. The combined effect of this myth-making apparatus would profoundly re-shape popular perceptions of rock’s history. As the Legends series lumped The Clash and The Bee Gees into the same exalted category and Behind the Music presented John Lennon, R.E.M., Motley Crue, and Kiss as equally worthy subjects of serious documentary treatment, the tensions which had once existed between artistic and commercial assessments of rock music began to be blurred beyond recognition. Upstart publications like Spin magazine might have been expected to challenge the rock establishment’s compromised criteria, but instead they exaggerated it. When Spin revealed its first list of “The Greatest Albums of All Time” ultra-obscure but artistically respected albums like Tom Waits’ Swordfishtrombones and The Minutemen’s Double Nickels on the Dime were honored alongside commercially popular but artistically trivial albums like George Michael’s Faith, begging the question: Under what criteria could all these albums be judged as “great”?

And that’s a great question, isn’t it?

Caress cites portions of album reviews to illustrate his point; it was embarrassing to read an allegedly independent rock critic raving about Bon Jovi’s 1988 New Jersey, admitting without irony that what was best about it was its “sales potential.” Other reviews are quoted, from journals once known as bastions of anti-commercial zeal and counter-cultural artistic standards, making (serious) reference to pleasing the record label’s stockholders! Rolling Stone had previously been so committed to a counter-cultural worldview and resistance to commercial label hype that they would (literally) write columns against the very ads that appeared in their own magazine. They routinely bit the hands that fed them, Caress shows, and record labels put up with it. There was in the early heady days of the rise of rock a shared assumption that art matters, that the worldview and visions of serious rock musicians put them in a category somewhat different then mere entertainers or peppy pop groups. Those who wrote their own songs, created their own arrangements, recorded in their own manner, wrote liner notes and crafted performance styles by their own aesthetic and political values were considered artists in ways that singers who just performed other people’s songs as dictated by the record company’s lust for singles and hits were not. And they were, at least in some outlets and venues, treated not as celebrities but as artists.

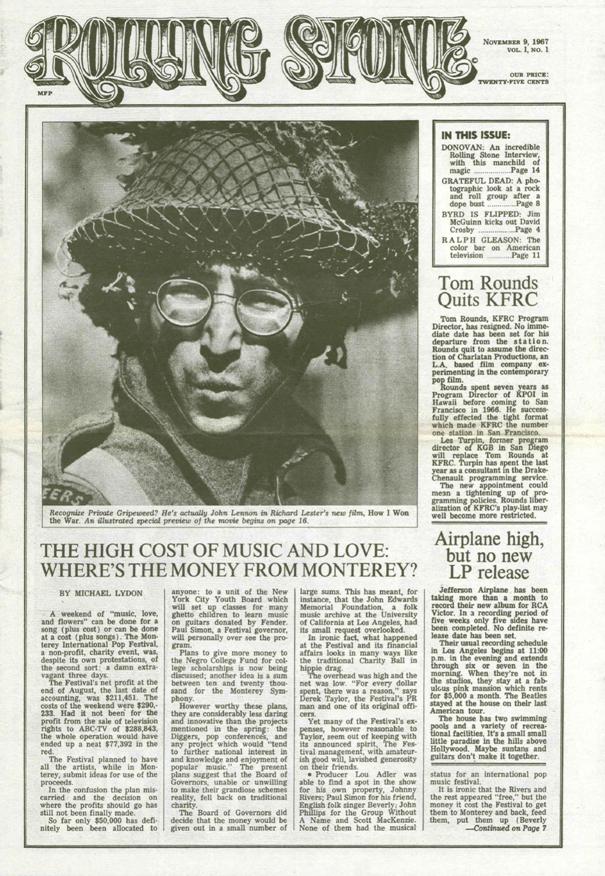

In the first issue of Rolling Stone – the one that had John Lennon in military garb, November 9, 1967 – Editor-in-Chief Jann Wenner (before he moved to New York and bought a Rolls Royce and hired a guy as Editor who was mostly known for doing swimsuit features) wrote,

In the first issue of Rolling Stone – the one that had John Lennon in military garb, November 9, 1967 – Editor-in-Chief Jann Wenner (before he moved to New York and bought a Rolls Royce and hired a guy as Editor who was mostly known for doing swimsuit features) wrote,

We have begun a new publication reflecting what we see as the changes in rock and roll and the changes related to rock and roll. Because the trade papers have become so inaccurate and irrelevant, and because the fan magazines are an anachronism, fashioned in the mold of myth and nonsense, we hope we have something here for the artists and the industry, and every person who “believes in the magic that can set you free.”

As Dylan went electric and influenced others, rock began to be taken seriously – in a way that, say Frank Sinatra or Chuck Berry or Elvis would never be — and these new rock critics, and serious underground radio stations, spread this new way of thinking about the art of rock music, the inevitable eventually happened. Perhaps is was the myth of Icarus, or “dumbing deviancy down” as one statesman put it years later. Or maybe there was something to that Robert Johnson story about selling one’s soul down at the crossroads.

BLAMING ZEP, KISS, AND THE ROCK CELEBRITY CULTURE

Mr. Caress doesn’t suggest those mythic options; he blames Led Zeppelin (and other social factors of the 70s) for what became sadly obvious: hard rock music became increasingly vapid, misogynist, formulaic, even as it because exceedingly commercially successful, with the painfully ironic confluence of rock and money — lots of money. We know much of this story, and how it led to the necessary rise of punk rock in response, although I learned much from Caress’s careful telling of this era, in many ways the “second wave” of serious artists in the rock scene.

PUNK

Punkers were of different ideological stripes, and different musical styles, even, and Caress parses the different kinds of punk and the varied impact of the Ramones, The Clash, The Sex Pistols, the anarchist or Marxist bands and the ugly nihilistic ones. The rise of punk became important in many ways, perhaps most significantly for eventually influencing a new movement which became known as grunge, based in Seattle.

And here is where the book really drills down, offering fascinating explanations and stories and band histories, exploring the influences (social, economic, artistic and more) of that Seattle scene.

GRUNGE IN SEATTLE

In a fabulously interesting description, Caress explains how rock tours in those years did not travel the many hours up from San Francisco to the Pacific Northwest so the isolated indie kids of Seattle didn’t know – they just hadn’t heard! – that there were tensions between punk artists and metal groups. Perhaps in every other major city in the world there were two big scenes, driven by competing, niche-oriented radio stations (outside of hit-driven pop, of course) and the social architecture of distinctive networks, nurtured by indie record stores, local rock newspapers, clubs and local artists doing regional touring — those who favored metal and hated punk and those who were punks and hated glam rock. In Seattle, apparently, kids listened to AC/DC and The Ramones; the indie record stores promoted Motley Crue and The Talking Heads.

In a fabulously interesting description, Caress explains how rock tours in those years did not travel the many hours up from San Francisco to the Pacific Northwest so the isolated indie kids of Seattle didn’t know – they just hadn’t heard! – that there were tensions between punk artists and metal groups. Perhaps in every other major city in the world there were two big scenes, driven by competing, niche-oriented radio stations (outside of hit-driven pop, of course) and the social architecture of distinctive networks, nurtured by indie record stores, local rock newspapers, clubs and local artists doing regional touring — those who favored metal and hated punk and those who were punks and hated glam rock. In Seattle, apparently, kids listened to AC/DC and The Ramones; the indie record stores promoted Motley Crue and The Talking Heads.

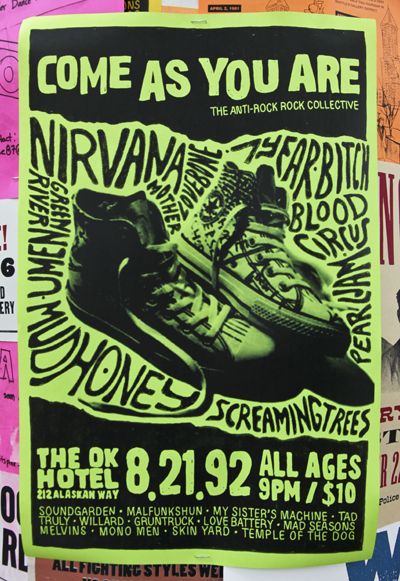

Out of that unusual mix emerged what became incredibly important for rock – a blended sound that was truly an alternative to the reigning radio paradigm and market trends and divergent sounds and fans. It wasn’t punk and it wasn’t metal, but anyone who has followed rock music in the last 25 years knows of Soundgarden and Mudhoney and Alice in Chains, the post-punk grunge of Kurt Cobain’s Nirvana and eventually Pearl Jam. (Not to mention a hundred copycats and wannabees as record label execs learned of the new commercial appeal of flannel and angst and set up oodles of new groups, posed as the next Nirvana or Pearl Jam. Caress names names and it is a trip down the 1990s memory lane.)

Out of that unusual mix emerged what became incredibly important for rock – a blended sound that was truly an alternative to the reigning radio paradigm and market trends and divergent sounds and fans. It wasn’t punk and it wasn’t metal, but anyone who has followed rock music in the last 25 years knows of Soundgarden and Mudhoney and Alice in Chains, the post-punk grunge of Kurt Cobain’s Nirvana and eventually Pearl Jam. (Not to mention a hundred copycats and wannabees as record label execs learned of the new commercial appeal of flannel and angst and set up oodles of new groups, posed as the next Nirvana or Pearl Jam. Caress names names and it is a trip down the 1990s memory lane.)

As kids, you see, some of these rising Seattle artists listened to groups like Kiss, say, and didn’t realize that the punkers thought that was stupid. Out of this uninformed openness came a new sound, a hybrid, that developed organically in the otherwise lame music scene in the Pacific Northwest, with a bunch of indie alt bands, Nirvana breaking out, leading the way, and Pearl Jam soon to follow. Legendary indie labels arose – Subpop comes to mind – and changed the face of rock music forever.

This was an era, you may recall, when there was terrible pop music on the air, boy bands galore, women singers known mostly as sexy dancers, groovy guys lip syncing fake British new wavers, mimicking what was a cool indie sound, dumbing it down, dumbing it down. The first wave of kids coming of age after an unprecedented family breakdown added sadness and disillusionment to the Gen X mix. Huge record labels and high impact mainstream radio were promoting all manner of upbeat superstars. (Things don’t change, it seems — in later chapters, Caress reports how big labels were pouring millions and millions into promoting one CD, a release by J-Lo, for example, but virtually nothing for her label-mates Wilco, who were dropped for not being blockbusters.) There were classic rock acts, still – Springsteen, of course, the ever present Rolling Stones, legacy tours of reunited oldsters. But the biggest selling album in history (up to that point) came from Seattle. Welcome to Alternative Nation.

But the biggest band in the world then was one that also emerged from a curious, soggy place, offering a blend of post-punk and alt-rock experimentation — the boys from Belfast, Ireland: U2.

U2

I loved the part of The Day Alternative Music Died that developed the history of the rise of grunge and the use of “alternative” as a catch-all description for a certain ethos and genre. MTV started their important show 120 Minutes (1986 – 2000) and Alternative Nation hosted by VJ Kennedy. (Remember her?) Bands of many different sounds and styles and visions became known as alternative. The Cure, Peter Gabriel, The Smashing Pumpkins, Bad Religion, Husker Du, Morrissey, even the Cranberries. R.E.M. became a darling of the critics and huge, huge sellers. (Even contemporary Christian bands started to take up unique stylings and edgier sounds that we called in those days “alternative” – and we still have their often amazing CDs in our shop.) The battle between commerce and art raged (as did the hostilities between fans of Kurt Cobain and those of Eddie Vedder, debating who had sold out, who was authentic.) But it was – given my own tastes then and now – Caress’s study of U2 in those years that most captivated me.

I loved the part of The Day Alternative Music Died that developed the history of the rise of grunge and the use of “alternative” as a catch-all description for a certain ethos and genre. MTV started their important show 120 Minutes (1986 – 2000) and Alternative Nation hosted by VJ Kennedy. (Remember her?) Bands of many different sounds and styles and visions became known as alternative. The Cure, Peter Gabriel, The Smashing Pumpkins, Bad Religion, Husker Du, Morrissey, even the Cranberries. R.E.M. became a darling of the critics and huge, huge sellers. (Even contemporary Christian bands started to take up unique stylings and edgier sounds that we called in those days “alternative” – and we still have their often amazing CDs in our shop.) The battle between commerce and art raged (as did the hostilities between fans of Kurt Cobain and those of Eddie Vedder, debating who had sold out, who was authentic.) But it was – given my own tastes then and now – Caress’s study of U2 in those years that most captivated me.

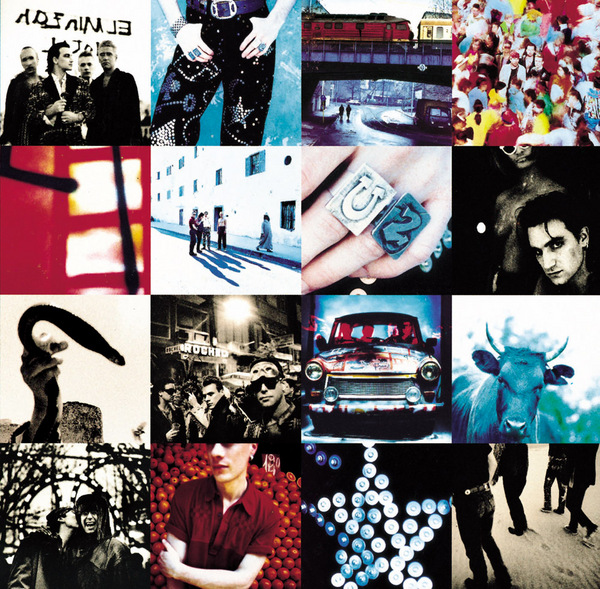

ACHTUNG BABY AND ZOOTV

It isn’t a new story – their neo-punk beginnings, the rising popularity of Joshua Tree, the mixed critical acclaim of Rattle and Hum, the charges of losing their way, and their majestic re-invention into an artfully complex, indie-type alternative force with the release of the brilliant Achtung Baby and the hyper ironic, postmodern ZOOTV tour. Caress gets it right, and frames their end of the century metamorphosis in light of the other musical options on offer those early years of the 1990s.

It isn’t a new story – their neo-punk beginnings, the rising popularity of Joshua Tree, the mixed critical acclaim of Rattle and Hum, the charges of losing their way, and their majestic re-invention into an artfully complex, indie-type alternative force with the release of the brilliant Achtung Baby and the hyper ironic, postmodern ZOOTV tour. Caress gets it right, and frames their end of the century metamorphosis in light of the other musical options on offer those early years of the 1990s.

Even as the U2 story is unfolding, Kurt Cobain and Eddie Vedder are major players in these middle chapters of The Day Alternative Music Died. Even if you are less interested in how Seattle became “the new epicenter of the alternative nation” or are not interested in the backstory of Lollapalooza, say, or Pearl Jam’s quixotic, principled campaign against Ticketmaster, this middle section of the book is still really interesting. There are good stories, brief album reviews that flow from chapter to chapter, even as Caress’s theme – the role of commerce and big business and how it affects artists – is never far from the details.

If you like learning about who hired whom to produce what, and how the funding and advertising and radio airplay and tour costs mattered, the rise and fall of record labels, and their executives, you will be more than intrigued. The conflicts between bands and their producers, their labels heads and the A&R guys — not to mention the corporate bean-counters are the stuff of legend. Apparently, these tensions really are ever-present in the performing arts, and this book exposes it within the alt music scene – people who were supposed to know better – in a powerful, compelling (and entertaining) way. More than a cautionary tale or a postmodern updating of Doctor Faustus, this amazing narrative helps us see the temptations of our times, the spirit of late modern capitalism which has the power to undo alternative forces and co-opt the most insistent artists and prophets among us.

If you like learning about who hired whom to produce what, and how the funding and advertising and radio airplay and tour costs mattered, the rise and fall of record labels, and their executives, you will be more than intrigued. The conflicts between bands and their producers, their labels heads and the A&R guys — not to mention the corporate bean-counters are the stuff of legend. Apparently, these tensions really are ever-present in the performing arts, and this book exposes it within the alt music scene – people who were supposed to know better – in a powerful, compelling (and entertaining) way. More than a cautionary tale or a postmodern updating of Doctor Faustus, this amazing narrative helps us see the temptations of our times, the spirit of late modern capitalism which has the power to undo alternative forces and co-opt the most insistent artists and prophets among us.

And it’s a blast, because all the while he is also telling us about everybody from Sonic Youth to Superchunk, Radiohead to Neko Case, Dave Grohl to Debbie Harry.

Even if this detailed coverage of the alternative music scene doesn’t seem interesting to you — lists of radio stations and rock critics and where they all stood on rising artists such as Black Flag or the Violent Femmes or Jane’s Addiction or Elvis Costello or Metallica (and who were the most principled in their art, who was most willing to compromise for the sake of commercial appeal) — I think this book will still win you over. What these most often underground bands or songwriters meant, and what it all meant to our popular culture, is truly fascinating and, I think, important. How they seemed to be largely co-opted is important. This whole story of commerce and consumerism helps us see some of what we saw in the much-discussed documentary The Merchants of Cool. It’s important.

Just for instance, here is Caress taking severe exception to Chuck Klosterman and his rock music appreciation memoir Fargo Rock City:

The problem with rock narratives in under-researched personal memoirs like Fargo Rock City is that they present a wildly inaccurate view of history, in this case downplaying the significance of the sea change that occurred when alternative music ousted glam rock as rock’s popular torchbearer, thus obscuring the reasons that such a shift took place in the first place. There were real reasons that Nirvana refused to tour with Guns N’ Roses in the early 90s; not least of which being the fact that the testosterone-fueled misogyny that GNR embodied was one of Kurt Cobain’s least favorite qualities in anyone, let alone a rival rock band. There were real reasons that, in the wake of the early 90s alternative revolution, glam rock was largely relegated to seedier fringes of cultural respectability: professional wrestling, strip clubs, and other places where the misogyny inherent in the music fit the less enlightened, predominantly male atmosphere. And there were real reasons for alternative music’s unprecedented burst of commercial success in the early 90s, which helped spur album sales to record heights and echoed rock’s late 60s surge in popularity.

ZEITGEISTY

Adam Caress, by the way, is himself a follower of Christ and has good insights about the zeitgeist. His own appreciation of indie artists of integrity (those “with something to say”) is evident.

own appreciation of indie artists of integrity (those “with something to say”) is evident.

Yet, this isn’t a book about Christian faith and he does not attempt to offer faith-based perspective on the nature of art or the religious ground motives and cultural narratives that allow for this particular dilemma within Western art. That is, he sort of implies or assumes that it is just a given that there is a dualism between those who do art – subversive, important, upsetting, even, and those who do not. Such views of art, and of commerce, are themselves rooted in certain (bohemian?) worldview assumptions, I suppose, and he does not make any attempt to discern where that comes from, or critique it at all. It may not be germane to this particular project, but it might have been helpful to explore just a bit the genealogy of the ideas that pervade the book.

(I recall being blown away once, decades ago, when I asked Calvin Seerveld about pop art like Andy Warhol, what the mass commercialization meant, where that was coming from and its import for contemporary culture. His answer seemed so tender and prophetic and insightful that I left the room and cried, moved and glad that somebody had such a profound understanding of the dangerous ideologies that pervade the discussions of faith and commerce, trendy subversive art and truly redemptive art.)

(I recall being blown away once, decades ago, when I asked Calvin Seerveld about pop art like Andy Warhol, what the mass commercialization meant, where that was coming from and its import for contemporary culture. His answer seemed so tender and prophetic and insightful that I left the room and cried, moved and glad that somebody had such a profound understanding of the dangerous ideologies that pervade the discussions of faith and commerce, trendy subversive art and truly redemptive art.)

Caress not only knows rock history (he “knows his scene cold, writing with an informed insider’s confidence” says literary critic Sven Birkerts, himself an amazing writer) he knows much about the contrasting philosophies of rock criticism. He takes us along wonderfully in a few key chapters in the second half of the book, starting with a study of mergers, acquisitions and the ultra-corporatization of music and how this lead to the “hyper-commercialization of rock” (think of the curious story of how Alanis Morissette was manufactured or the blip of Limp Bizkit.)

POPTIMIST AUTHENTIC INAUTHENTICITY? OR: IS IT ART?

In a brilliant chapter that starts off with a close reading of Radiohead (from Okay Computer to Kid A) he shows how these significant artists were received and reviewed. Caress calls this chapter “The End of Rock Criticism” and he takes on both Chuck Klosterman (and his fascinating low-brow book Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs) and the heady postmodern critics such as sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and his book Distinction: A Social Critique of Judgement of Taste and how that influenced Carl Wilson’s popular book on Celine Dion (with the subtitle A Journey to the End of Taste.) Caress argues that these deconstructive critics overstate how class and gender and race influences us, thereby eroding any lasting principles or enduring values to art criticism. (“All art is fake” one says, while another writes of “authentic inauthenticity” and Wilson himself speaks of “a genuine fake.”) This thoughtful chapter is one of the more demanding ones of the book and is, I think, brave and valuable.

In a brilliant chapter that starts off with a close reading of Radiohead (from Okay Computer to Kid A) he shows how these significant artists were received and reviewed. Caress calls this chapter “The End of Rock Criticism” and he takes on both Chuck Klosterman (and his fascinating low-brow book Sex, Drugs, and Cocoa Puffs) and the heady postmodern critics such as sociologist Pierre Bourdieu and his book Distinction: A Social Critique of Judgement of Taste and how that influenced Carl Wilson’s popular book on Celine Dion (with the subtitle A Journey to the End of Taste.) Caress argues that these deconstructive critics overstate how class and gender and race influences us, thereby eroding any lasting principles or enduring values to art criticism. (“All art is fake” one says, while another writes of “authentic inauthenticity” and Wilson himself speaks of “a genuine fake.”) This thoughtful chapter is one of the more demanding ones of the book and is, I think, brave and valuable.

Caress helps us understand much with a blistering few paragraphs summarizing the rock music ethos of the early 2000s, where he exposes what some call “poptimists” and how

…any artist or critic who makes either explicit or implicit claims to the transcendent aesthetic possibilities of art can be reflexively dismissed as ‘pretentious’ or ‘elitist.’ And thus, by marginalizing any and all appeals to artistic standards, poptimists severely weakened the place of traditional criticism, which had long functioned as one of Western society’s few remaining bulwarks against the purely commercial domination of popular culture.

He continues,

In the end, the poptimists in the early 2000s resulted in a devaluation of the place of art and artists in society. And in their place, pop apologists were relentlessly endorsing commercially-driven, celebrity-centric pop culture as a valid substitute. In fact, during the first few years of the new millennium, poptimist revisionism was working in concert with both rock establishment mythology and corporate commercial marketing in order to marginalize the perceived importance of the unique creative visions of individual artists.

… influential cultural critics were busy spreading the “poptimist” belief in the value of commercial pop music and disparaging the “rockist” values of artistic substance and authenticity…

And, of course, the corporate music industry machine was spending hundreds of millions of dollars each year to convince the record-buying public that its commercial approximations of art had rendered individual creative visions obsolete. It was in this hostile environment that a fragile group of independent music labels and artists was coalescing into what would come to be known as the “indie” music scene.

GOLDEN AGE OF INDIE (AND THE EMPIRE STRIKES BACK)

Which takes us to the final four chapters, a collection of several very important essays about the latest dilemmas in the digital age, the battle about Napster, the rise of yet another epoch of indie labels, the rise of self-publishing, Pitchfork reviews, live streaming, fan blogging, and so forth. He refers to this as “the business of indie’s golden era” and — still — must explore how “commerce strikes back” with the rise of shows like American Idol and the

Which takes us to the final four chapters, a collection of several very important essays about the latest dilemmas in the digital age, the battle about Napster, the rise of yet another epoch of indie labels, the rise of self-publishing, Pitchfork reviews, live streaming, fan blogging, and so forth. He refers to this as “the business of indie’s golden era” and — still — must explore how “commerce strikes back” with the rise of shows like American Idol and the  on-going “commercial marginalization of art.” Again, you may not agree with his assessment, but this is rich, very contemporary stuff, and I highly recommend it for those who ought to be thinking about the issues of the day.

on-going “commercial marginalization of art.” Again, you may not agree with his assessment, but this is rich, very contemporary stuff, and I highly recommend it for those who ought to be thinking about the issues of the day.

For just a glimpse into how Caress discerns this, again, in more recent times and from influential voices, he cites a significant New York Times piece on the major label promotions of major performers (Carrie Underwood, Britney Spears) as “the cure for the evils of today’s music business.” As if this corporate-driven, top-down paradigm for music creation doesn’t erode the significance of artistically independent rock artists.

Caress then dissects an NPR piece about American Idol (which, NPR’s leading music critic Ann Powers says glowingly has “reshaped the American songbook.”)

Power’s choice of words — by which songs were “sold,” musical gifts were turned into “products,” and performers were rewarded for their “entrepreneurship” — was a telling indicator of the way mainstream music criticism was coming to use commercial terminology in order to assess artistic merit.

A GREAT SERVICE, CHILLINGLY PERSUASIVE

In The Day the Alternative Music Died… Mr. Caress has offered us a very great service, not only surveying the crazy years of the rise and demise of rock and roll, but framing it in terms of the ping and pong of different movements and styles, all of which, in one way or another, were reacting to this fundamental tension between art and commerce, a tension which may be a symptomatic issue betraying bigger struggles — perhaps a framework that contrasts ideologies of freedom vs control, contrasting visions between the lefty counter-culture and the established dominant culture, how movements working for cultural reformation and social change are often neutralized by the enticements of cultural accommodation. These assumed dualisms may be rooted in deeper perceptions about the nature of things. Ultimately, I think some of this comes because there are many who presume a large dichotomy between faith and reason — I think of generative works like Iain McGilchrist’s massive The Master and the Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World or an old favorite, that we still stock, The Secular Squeeze: Reclaiming Christian Depth in a Shallow World by John F. Alexander.

In The Day the Alternative Music Died… Mr. Caress has offered us a very great service, not only surveying the crazy years of the rise and demise of rock and roll, but framing it in terms of the ping and pong of different movements and styles, all of which, in one way or another, were reacting to this fundamental tension between art and commerce, a tension which may be a symptomatic issue betraying bigger struggles — perhaps a framework that contrasts ideologies of freedom vs control, contrasting visions between the lefty counter-culture and the established dominant culture, how movements working for cultural reformation and social change are often neutralized by the enticements of cultural accommodation. These assumed dualisms may be rooted in deeper perceptions about the nature of things. Ultimately, I think some of this comes because there are many who presume a large dichotomy between faith and reason — I think of generative works like Iain McGilchrist’s massive The Master and the Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World or an old favorite, that we still stock, The Secular Squeeze: Reclaiming Christian Depth in a Shallow World by John F. Alexander.

The Day Alternative Music Died is, as critic Sven Birkerts notes, “chillingly persuasive.” And, I think, it will drive you to deeper questions, bigger questions, which is always the sign of a good book.

It is good for those who want a handle on the zeitgeist, the history of how we got to indie and maybe what it means to resist captivity to the powers that be. And it will push you not only to enjoy new music, or revisit old albums, but it will help you think about all manner of matters.

For anyone interested in rock music, you will love this book. You may not agree with his views of this band or that – and, man, does he name a lot! — but you will learn new stuff, I’m sure, and love the ride, or at least most of it. Mr. Caress takes his subject seriously, but isn’t dry, and is obviously an enthusiastic fan, even a delightfully diverse one. He does a fabulous job looking at the art itself (and the personal struggles with popularity, commercial success, relationships with labels

For anyone interested in rock music, you will love this book. You may not agree with his views of this band or that – and, man, does he name a lot! — but you will learn new stuff, I’m sure, and love the ride, or at least most of it. Mr. Caress takes his subject seriously, but isn’t dry, and is obviously an enthusiastic fan, even a delightfully diverse one. He does a fabulous job looking at the art itself (and the personal struggles with popularity, commercial success, relationships with labels  and rock critics) of significant rock artists. He takes us from Dylan on through the David Geffen “Asylum Records” years (and the rise of the likes of Jackson Browne, Joni Mitchell, Tom Waits, Linda Ronstadt, CSN, The Band) to various schools of punk, the rise of the Seattle grunge sound and other offbeat, artsy movements within “alternative nation” and, near the end, finally exploring the future of the indie scene by documenting the rise of indie

and rock critics) of significant rock artists. He takes us from Dylan on through the David Geffen “Asylum Records” years (and the rise of the likes of Jackson Browne, Joni Mitchell, Tom Waits, Linda Ronstadt, CSN, The Band) to various schools of punk, the rise of the Seattle grunge sound and other offbeat, artsy movements within “alternative nation” and, near the end, finally exploring the future of the indie scene by documenting the rise of indie  labels, advancing artists like Sufjan Stevens, Death Cab for Cutie, The National, Grizzly Bear, Arcade Fire, and more.

labels, advancing artists like Sufjan Stevens, Death Cab for Cutie, The National, Grizzly Bear, Arcade Fire, and more.

SERIOUS FUN

I have read a lot of books about the history of rock music, some of which have been a delight, and some which have been culturally illuminating. This is one of the rare ones, bringing together a fan’s love for the music and rock culture, and a bit of serious artistic and ideological excavating, digging between the lines, not only of the lyrics, but of the contracts, not just the rock propaganda, but its best critics, not just of the artists lives, but the labels and their shareholders and what it all may mean.

The subtitle “Dylan, Zeppelin, Punk, Glam, Alt, Majors, Indies, and the Struggle Between Art and Money for the Soul of Rock“ gives you more than a hint of the story, but you have to read The Day the Alternative Music Died to see where he goes with it all, the story he tells, the insights learned along the way.

Interestingly, it is not a pessimistic book, not even a jeremiad against the men in suits and their co-opting of alternative music, although there is some of that. Better, Caress ends with a rumination on the vocation of an artist, using religiously-rich language of calling. He teaches music business at a Christian college (Montreat College, in North Carolina) so it is evident that he embraces this high view of the notion of vocation, and a rich appreciation for the role of the arts. I might note that he is a person of hope. He knows God’s concern for cultural renewal, desires Christ-like human flourishing, and he knows that signs of life – as Paste magazine sometimes puts it – can break out all over, despite all odds. We embrace common grace for the common good, Adam once heard Steve Garber say, in a powerful Garber sermon at Montreat. The story Caress tells here, painful and even disturbing as it sometimes is, is an example of that. Common grace, indeed.

***

A WARNING, A COMMENT, A PERSONAL NOTE ON WHY I CARE

Allow me a heads-up, a quick observation, and a very personal note.

Firstly, this is not a book pitched to a religious readership, despite the author’s employment at an institution with evangelical commitments. Citing as he does many interviews with rock stars and counter-cultural critics, sober and otherwise, The Day Alternative Music Died, shall we say, is in need of one of those Parental Warning stickers Tipper Gore got slapped on the cover of vulgar albums so many years ago.

More interesting, I hope, is this comment: Caress does not, unfortunately in my view, talk at all about contemporary Christian music, the artists, labels, festivals, journalism, or their own unique  predicaments in this arena. Obviously, there was a group of artists whose art was supposed to mean something vital, who knowingly called themselves an alternative to the mainstream (and some were, in fact, fairly involved in the “alternative” scene, even in Seattle) and whose record labels were soon submerged in commercialization and crass materialism. That story – hinted at in William Romanowski’s highly respected Pop Culture Wars: Religion and the Role of Entertainment in American Life – is perhaps a book yet to be written, one which itself could be pretty sordid.

predicaments in this arena. Obviously, there was a group of artists whose art was supposed to mean something vital, who knowingly called themselves an alternative to the mainstream (and some were, in fact, fairly involved in the “alternative” scene, even in Seattle) and whose record labels were soon submerged in commercialization and crass materialism. That story – hinted at in William Romanowski’s highly respected Pop Culture Wars: Religion and the Role of Entertainment in American Life – is perhaps a book yet to be written, one which itself could be pretty sordid.

(As Adam throws down literally hundreds of band names and record labels, some obscure, I kept waiting for a mention of Michael Roe and the 77s, or Bill

(As Adam throws down literally hundreds of band names and record labels, some obscure, I kept waiting for a mention of Michael Roe and the 77s, or Bill

Mallonee and VOL,

Mallonee and VOL,  David Bazen and Pedro the Lion, Chagall Guevara, Mark

David Bazen and Pedro the Lion, Chagall Guevara, Mark  Heard, or at least Christian alt-indie labels like Tooth & Nail Records. Tooth & Nail, you may recall, did all sorts of creative stuff, from the shoegazers Starflyer 59 to hardcore bands like Project 86 and Norma Jean, offering a platform for the clever electronica of Joy Electric, not to mention some really weird, art-house indie folk — the breathtaking creativity of Danielson, with his early Sufjan Stevens connections.)

Heard, or at least Christian alt-indie labels like Tooth & Nail Records. Tooth & Nail, you may recall, did all sorts of creative stuff, from the shoegazers Starflyer 59 to hardcore bands like Project 86 and Norma Jean, offering a platform for the clever electronica of Joy Electric, not to mention some really weird, art-house indie folk — the breathtaking creativity of Danielson, with his early Sufjan Stevens connections.)

I note this because, well, we here at Hearts & Minds sell this stuff. Some aficionados have said that we had among the best Christian music selection in the East Coast. Music is, sadly, increasingly a sideline for us, but we are one of those bookstores that still carry CDs of all sorts, from classical to jazz (we recently got the latest Bill Carter & Presbybop CD, Jazz for the Earth. You should check it out!) We just put the fantastic new  Indigo Girls One Lost Day on the shelves this week; any day we’ll have the wonderful Phil Madeira project, Mercyland 2: More Hymns for the Rest of Us. Hopefully, I’ll soon review the latest Bill Mallonee masterpiece, Lands and Peoples (who actually writes about this complex business of music, faith, art and commerce.) We are happy that groups like Mumford and Sons, The Civil Wars, Need to Breathe and mewithoutyou and yes, all of Bruce Cockburn and U2 are still around, right there on our music display.

Indigo Girls One Lost Day on the shelves this week; any day we’ll have the wonderful Phil Madeira project, Mercyland 2: More Hymns for the Rest of Us. Hopefully, I’ll soon review the latest Bill Mallonee masterpiece, Lands and Peoples (who actually writes about this complex business of music, faith, art and commerce.) We are happy that groups like Mumford and Sons, The Civil Wars, Need to Breathe and mewithoutyou and yes, all of Bruce Cockburn and U2 are still around, right there on our music display.

***

My first real job was in a record store and my first serious creative writing project, turned in to Mr. Trimmer in high school English, was a piece about selling a country music 45 to a blue collar customer at the Platter Palace in Gettysburg, PA. My bosses there in 1971 taught me about retail and commerce and a bit about record labels and industry payola. And here I am today, trying to figure out how to sell CDs, music that matters, not unlike books, in an era when it looks like indie book and music stores are too soon a thing of the past. The day the alt music died? My own personal crisis is less about the music dying than the music store dying. And the bookstore fading. A vested commercial interest? Oh yes, yes indeed. Can passion and art and grand purpose survive hard economic realities? In my life, I am not optimistic, but I take some courage and hope from the stories of daring artists and indie labels and faithful fans described in Caress’s splendid, splendid book. And for that, for now, I am grateful.

My first real job was in a record store and my first serious creative writing project, turned in to Mr. Trimmer in high school English, was a piece about selling a country music 45 to a blue collar customer at the Platter Palace in Gettysburg, PA. My bosses there in 1971 taught me about retail and commerce and a bit about record labels and industry payola. And here I am today, trying to figure out how to sell CDs, music that matters, not unlike books, in an era when it looks like indie book and music stores are too soon a thing of the past. The day the alt music died? My own personal crisis is less about the music dying than the music store dying. And the bookstore fading. A vested commercial interest? Oh yes, yes indeed. Can passion and art and grand purpose survive hard economic realities? In my life, I am not optimistic, but I take some courage and hope from the stories of daring artists and indie labels and faithful fans described in Caress’s splendid, splendid book. And for that, for now, I am grateful.

The Day Alternative Music

Died

regularly $16.99

our sale price $13.60

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333