We have mentioned the most recent Jim Wallis book a few times since it released earlier this year and are thrilled to partner with Brazos Press (part of the Baker Publishing Group) to offer it at a bigger discount. I know it is a hardback, and not a light-hearted read, but we think it would make a fabulous book group title, a fine book for an Adult Sunday School class or a small group. Heaven knows it is a topic which deserves some extra attention here near the end of a very hard year.

We have mentioned the most recent Jim Wallis book a few times since it released earlier this year and are thrilled to partner with Brazos Press (part of the Baker Publishing Group) to offer it at a bigger discount. I know it is a hardback, and not a light-hearted read, but we think it would make a fabulous book group title, a fine book for an Adult Sunday School class or a small group. Heaven knows it is a topic which deserves some extra attention here near the end of a very hard year.

We are here offering a special rare deal (an offer cooked by the good people at Baker Publishing) for anyone buying at least 20 copies.

You can get 50% off if you buy 20.

That makes them just $11.00 for a nice hardcover.

AND you get some special resources to help you process the material, including free access to a good study guide and an exclusive, six week on-line webinar conversation with Mr. Wallis. It’s a really good deal, and would make for a very special small group event.

You can use our link below and if you order 20 we’ll hook you up with the extra connections.

Jump down to the link to our order form right away, if you’d like. If you aren’t sure about this title, though, let me tell you all about it.

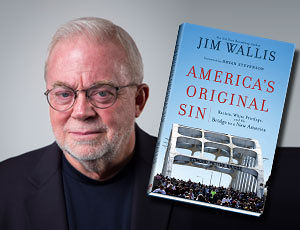

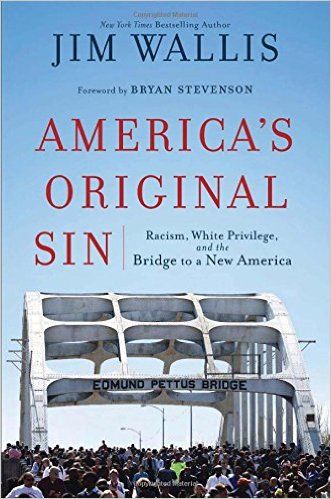

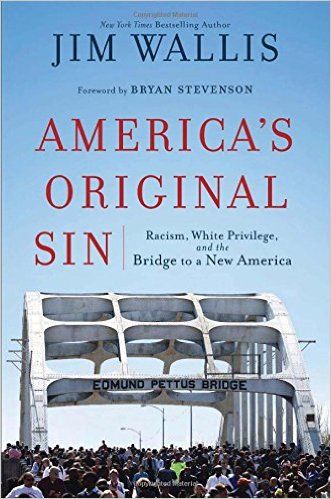

American’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America (Brazos Press; usually $21.99) is a book that has been long in coming with Jim Wallis finally visiting a topic in a book length treatment that has been on his heart for most of his lifetime.

American’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America (Brazos Press; usually $21.99) is a book that has been long in coming with Jim Wallis finally visiting a topic in a book length treatment that has been on his heart for most of his lifetime.

He opens the book with the story (which he has shared before) of having grown up in the 60s in the suburbs of Detroit very involved in a mostly healthy, friendly, tight-knit if rather fundamentalist Christian denomination. As racial discrimination and social inequities deepened, as Dr. King preached and racial troubles become more known (if still not particularly understood among white church folks) and the voices of African American writers, poets, rock stars, and activists became more strident, Jim asked tough questions within his own faith community. His parents were leaders in that evangelical congregation and they seemed to unite in one voice with the other adults in the church: such questions not welcome. God didn’t care much about politics, and faith was personal. Hearing this drove Jim out of his church and those years were painful as he sought a faith that was personal “but never private” and a renewed conversion to the ways of Jesus by hearing the voices and taking seriously the views of the oppressed. Matthew 25 became a key to his new spiritual search.

Importantly, in those high school years in Detroit he was hanging around other teens and young adults, like Butch, with whom he shared a job in downtown Detroit. Butch was black and he allowed Jim into his home to meet his parents, into a family that was in some ways similar and yet in some ways very different than his own. In those days “social location” was a fairly new idea in contemporary theological studies and Jim wandered into it squarely: where you stand, where you live, what you see day by day, colors how you experience life and how you see society (and faith!) Given his early, intense experiences with families that lived in urban ghettos, who had dangerous encounters with the police, who mistrusted the government, who saw Christ as a liberating King with exceptional relevance for their daily social and political life, I would suspect he didn’t need Francis Schaeffer to tell him by the early 70s about worldviews. He didn’t need to overcome the evangelical dualism of separating faith and culture or prayer and politics because he was so very informed by the experience of his new black friends and their lively, socially-engaged faith.

Jim, I suppose you know, didn’t stay out of the church for long. He found other like minded friends who were reading Thomas Merton or Jacque Ellul or Bill Pannell and started an underground-type rag called The Post American; I am proud to have a copy of that first controversial edition. He attended a firmly evangelical seminary (Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) and wrote a book entitled Call to Conversion which is still in print, and still one of the most important for my own journey.

Jim, I suppose you know, didn’t stay out of the church for long. He found other like minded friends who were reading Thomas Merton or Jacque Ellul or Bill Pannell and started an underground-type rag called The Post American; I am proud to have a copy of that first controversial edition. He attended a firmly evangelical seminary (Trinity Evangelical Divinity School) and wrote a book entitled Call to Conversion which is still in print, and still one of the most important for my own journey.

If you look carefully you’ll see the cleverness of the cover of this second edition — the newspaper and the Bible being read together — which, of course, plays with the famous line from Karl Barth and those who were resisting Hitler out of Christian conviction.

I didn’t know it in the early to mid-70s that Wallis’s story was a larger more dramatic version of my own, but I resonated deeply with the new authors and writers and young evangelical leaders I was learning about in what eventually became Sojourners. Their appreciation of some of the voices of the counterculture drew me in and their theological vision made sense. It was Jim and his scruffy band of renewed and radical evangelicals who introduced me to names like John Perkins, Caesar Chavez, Dan and Phil Berrigan, Dorothy Day, Senator Mark Hatfield, Richard Mouw and other ‘zines like Daughters of Sarah and The Other Side. That the woman I would soon marry was visiting Koinonia Farms in Georgia and meeting Ladon Sheets and Millard Fuller and learning about Baptist integrationist Clarence Jordon is fascinating–those were people I came to admire, too, and some are now discussed in Wallis’s new book. The book is dedicated to an African American leader we came to appreciate in those years and who was nearly an Uncle to Wallis’s own children, Dr. Vincent Harding. His books such as There Is a River and Hope and History not only documented the civil rights movement but implored us to keep telling the stories.

And so we do.

Such voices compose the backstory of much of Wallis’s very contemporary study, America’s Original Sin. In some derivative, third-hand way, it is part of the backstory of Hearts & Minds and why we carry this book and why we are encouraging you to form a group to study this book. It’s a good story we all could stand to be a part of.

Which is all just a way of saying that we care about the work Wallis does, have read all his books, have hosted him here at the bookstore, and think that this new one is truly worthy your consideration. Agree or not with every detail, it is a great, great book to discuss together.

Especially with this limited time offer of deep discounts and an opportunity for your group or class to actually converse with Jim about the book.

American’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege and the Bridge to a New America is among his best. It is, as they say, his wheelhouse. Some of it was surely written on a quiet study retreat. It’s good he took the time and effort to share more thoroughly the fire that has been in his bones a long, long time on this topic. Few writers today can tell stories from his friendship with Desmond Tutu or Alan Boesak or Dr. William Barber II or Cornel West. It is beautiful to see white evangelicals like Mark Labberton and black church preachers like Otis Moss and Cynthia Hale global leaders like Geoff Tunnicliffe offering endorsements. Wallis has studied and learned and written well.

American’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege and the Bridge to a New America is among his best. It is, as they say, his wheelhouse. Some of it was surely written on a quiet study retreat. It’s good he took the time and effort to share more thoroughly the fire that has been in his bones a long, long time on this topic. Few writers today can tell stories from his friendship with Desmond Tutu or Alan Boesak or Dr. William Barber II or Cornel West. It is beautiful to see white evangelicals like Mark Labberton and black church preachers like Otis Moss and Cynthia Hale global leaders like Geoff Tunnicliffe offering endorsements. Wallis has studied and learned and written well.

But some of it was surely scribbled out in the streets, interviewing people in Ferguson, discussing issues of mass incarceration and the need for reform in community policing, learning in workshops and activist teach-ins about racial bias, profiling, and the like. The stories that have emerged in recent years that have found their way into the book show that there is a new generation of leaders and Wallis is not only offering us good information, but he’s learning new stuff as he goes, listening well to this new movement for social change.

But some of it was surely scribbled out in the streets, interviewing people in Ferguson, discussing issues of mass incarceration and the need for reform in community policing, learning in workshops and activist teach-ins about racial bias, profiling, and the like. The stories that have emerged in recent years that have found their way into the book show that there is a new generation of leaders and Wallis is not only offering us good information, but he’s learning new stuff as he goes, listening well to this new movement for social change.

I suspect that many readers of BookNotes know a bit about the Bible’s call to the church to be more multi-ethnic, the spiritual need for racial healing and reconciliation, the gospel truths that point the way towards the beloved community. I trust that you know about some of my earlier writing on this topic, and the books we’ve most eagerly recommended. I hope you’ve used them. See some of our previous BookNotes lists here and here and here.

If you have never tackled this topic before, and desire a deeply gospel-centered, evangelically-minded, Biblical reflection on this race and racism, maybe Living in Color: Embracing God’s Passion for Ethnic Diversity by Randy Woodley (IVP; $18.00 or Gracism: The Art of Inclusion by David Anderson (IVP; $17.00) might be great to start with. I certainly think Chan-Rah’s Many Colors: Cultural Intelligence for a Changing Church (Moody; $14.99) is useful, a good overview of our situation and the

If you have never tackled this topic before, and desire a deeply gospel-centered, evangelically-minded, Biblical reflection on this race and racism, maybe Living in Color: Embracing God’s Passion for Ethnic Diversity by Randy Woodley (IVP; $18.00 or Gracism: The Art of Inclusion by David Anderson (IVP; $17.00) might be great to start with. I certainly think Chan-Rah’s Many Colors: Cultural Intelligence for a Changing Church (Moody; $14.99) is useful, a good overview of our situation and the  shifts in

shifts in  the cultures of the West.

the cultures of the West.

We really promoted Lisa Sharon Harper’s The Very Good Gospel: How Everything Wrong Can Be Made Right over and over this summer (and loved hosting her at a special Hearts & Minds lecture out in Pittsburgh.) I do hope you recall our review of that.

A recent one which I reviewed at BookNotes the week it  came out earlier this spring is Heal Us, Emmanuel: A Call for Racial Reconciliation, Representation, and Unity in the Church edited by Doug Serven (Storied Communications; $16.99) which emerged out of pastors in the conservative Presbyterian Church of America (PCA.) We know some of the contributors to this book full of honest lament and struggle, and commend them for putting it together. It is an important contribution and we highly recommend it.

came out earlier this spring is Heal Us, Emmanuel: A Call for Racial Reconciliation, Representation, and Unity in the Church edited by Doug Serven (Storied Communications; $16.99) which emerged out of pastors in the conservative Presbyterian Church of America (PCA.) We know some of the contributors to this book full of honest lament and struggle, and commend them for putting it together. It is an important contribution and we highly recommend it.

Any number of these basic sort of guides to a wholistic gospel that offers insight into racial diversity and a move towards deeper understanding would be great.

But Wallis’s recent book goes deeper, even though it isn’t difficult to read and is not dense or dry.

America’s Original Sin goes deeper in three ways.

America’s Original Sin goes deeper in three ways.

First, it examines the recent tensions created by – or brought to a head by – the police shootings of the last few years. He explains the crisis situations in cities like Ferguson and Baltimore, looking at the backgrounds of those places, reporting on things he learned from interviews with folks on the ground, and citing the reports and documents that came out of the investigations after those tragic situations.

It is obvious that Wallis is wanting to stand with those who have been oppressed, he wants us to repent of complicity in systems and structures of injustice (including police misbehavior) and he is blunt in his denunciation of racist undertones in the hard stuff we see day by day by day. Some folks will think his bias gets the best of him at points, but fair readers will certainly give him credit for wading through lots of conflicting testimony and many perspectives on these episodes. He is careful and attempts to be balanced. He listens to conservative journals and cites preachers and pundits like the Southern Baptist Russell Moore and, in a chapter about restorative justice and prison reform, Chuck Colson.

A few hot-heads on the internet have jumped to awful conclusions about Wallis, insisting he is not to be trusted, but I’d advise you to read the book and make up your own mind. Valid and thoughtful critiques can be made, and not everyone will find all of his evidence compelling. There’s a few things I wish he might have said that he underplays. Why not read it with others and with the help of a discerning community of readers, together form your own opinion?

Again, this great book offers more than moral rhetoric about unity or spiritual talk about reconciliation. This is a step deeper into the conversation, studying the President’s Task Force, evaluating documents that comes the U.S. Department of Justice, and helping us appreciate some of the data and proposals that has emerged from some of the best think tanks and civil rights research agencies.

If you read modern magazines or listen to media outlets like NPR you’ve certain heard good scholars and pundits and researchers opine on topics related to this question of race in America, and Wallis seems to know about the best thought leaders out there. I think of him as a passionate prophetic preacher, a bit of a public theologian, but he’s studied this policy stuff well, and he knows how to bring just enough data and scholarship to help us know what we need to know. It is very informative and I found it very compelling.

He cites data from nonprofits like the Equal Justice Initiative and The Sentencing Project and quotes thinkers such as Michelle Alexander and Bryan Stevenson (who wrote the forward) as well as some of our finest historians about things like Affirmative Action. The footnotes are remarkable, drawing on articles about Community Policing and Restorative Justice. This stuff could be daunting but Jim navigates the social science and the policy proposals deftly, and he brings this call to reform always back to the Biblical call to repent. That is, he nicely makes this book a very useful handbook to up-to-date evaluations of our troubled current state of race relations, but roots his evaluation in a classic, solid of foundation of Biblical teaching and spiritual conversion.

He cites data from nonprofits like the Equal Justice Initiative and The Sentencing Project and quotes thinkers such as Michelle Alexander and Bryan Stevenson (who wrote the forward) as well as some of our finest historians about things like Affirmative Action. The footnotes are remarkable, drawing on articles about Community Policing and Restorative Justice. This stuff could be daunting but Jim navigates the social science and the policy proposals deftly, and he brings this call to reform always back to the Biblical call to repent. That is, he nicely makes this book a very useful handbook to up-to-date evaluations of our troubled current state of race relations, but roots his evaluation in a classic, solid of foundation of Biblical teaching and spiritual conversion.

One chapter in AOS called “From Warriors to Guardians” is an excellent overview of questions of race and policing. There is a chapter on mass incarceration and more faithful ways to think about crime (“The New Jim Crow and Restorative Justice”) and there is a chapter in immigration reform.

This whole book is a great case study of exploring “through the eyes of faith” the policy reforms we need to consider, ideas that need to be embodied in our social architecture. That is, he is taking seriously Christ’s call to be agents of public justice for the sake of the common good; he is showing us how to take steps as a people to rectify some of our broken social systems. Good feelings about racial diversity aren’t enough; talk about forgiveness and grace aren’t enough; we must educate ourselves about what can be done, what needs to change, how to resist the tendency to be complicit with unjust practices and social organization.

Part of this — one very, very good chapter — reflects on what we call white privilege. I’ll come back to that in a bit, but it is another example of how American’s Original Sin is inviting us to an experience of study that is a bit deeper.

For those who were able to join us in Pittsburgh when we hosted Jim’s colleague Lisa Sharon Harper, you may recall she highly recommended that we take the Harvard implicit racial bias test. Jim recommends a webpage hosted by the Kirwan Institute for the Study of Race and Ethnicity at Ohio State University as a “great place to start to get valuable implicit bias information.” (Did you know there is even an annual report on the “state of the science” reviewing the implicit racial bias social research? Wallis cites it. Fascinating.)

AOS goes a bit deeper in a second way, not just by exploring serious policy documents and research and interpreting them for church-based readers, but by calling us to a robust interpersonal conversation.

AOS goes a bit deeper in a second way, not just by exploring serious policy documents and research and interpreting them for church-based readers, but by calling us to a robust interpersonal conversation.

He insists that it is long past time for white parents to invite their black and other minority friends to level with them about their own experiences. This is hard stuff and although any number of books have recommended better friendships and more candid conversations, Wallis is clear and wise and helpful in saying what this might entail, how to pursue it, and what it might cost us all if we move in a direction of having such awkward, hard conversations. In a way, even though this book includes complex analysis and plenty of informative facts, it is a deeply personal book. It is about beginning or renewing conversation.

He insists that it is long past time for white parents to invite their black and other minority friends to level with them about their own experiences. This is hard stuff and although any number of books have recommended better friendships and more candid conversations, Wallis is clear and wise and helpful in saying what this might entail, how to pursue it, and what it might cost us all if we move in a direction of having such awkward, hard conversations. In a way, even though this book includes complex analysis and plenty of informative facts, it is a deeply personal book. It is about beginning or renewing conversation.

And then there’s that social location thing, again: we have to be in some kind of proximity to people unlike ourselves, and we have to have some sort of social intelligence to learn to reach out well across differences. Jim talks honestly from his own experiences of moving out of his own comfort zone over the years, from church planting in urban DC , being mentored by Gordon Crosby of Church of the Savior, and being inspired by the call to live among people of need coming from John Perkins and the CCDA. He affirms the younger voices such as Shane Claiborne and his Simple Way Community in Philadelphia.

He opens the book with a plea for a new conversation, and talks about “the talk” parents of black children have to have. He comes back to it later, too:

It’s time for a new conversation on race in America, and this time it will be a new generational discussion. The old talk is the one that black and brown parents still have with their children about how to behave in the presence of police – to protect themselves from them – an almost universal conversation that white parents know little about, as we discussed in chapter 1. The new talk is to make that old talk known to white parents and to together have a new conversation about the kind of country we want for all our children. Again, the issue is proximity. Our separated racial geography prevents those new talks from ever happening, so the changing of our geography has to be deliberate.

He then looks at three great venues for such new conversations (even talks about “the talk”) where that can happen: schools, sports, and local congregations.

He then looks at three great venues for such new conversations (even talks about “the talk”) where that can happen: schools, sports, and local congregations.

He quotes his wife Joy who reminds us that “diversity doesn’t just happen.” She and Jim have been PTA parents and he has coached his two boys and their teams in serious baseball. (If you don’t know that Wallis likes baseball, you don’t know Wallis!) These are good suggestions and down to Earth ideas for those of us who can’t go heading out to national protests or who aren’t asked to work with faith leaders in cities throughout the county. This is Jim writing out of his experience with global experience — from Detroit to South Africa, from DC to Ferguson — but also as an experienced localist, a coach, a parent, a guy in the neighborhood, and it is good stuff.

So America’s Original… goes a little deeper than some good books on racial reconciliation and multi-ethnic ministry by interpreting the social science on this and giving us the data and insight about the policy debates around urban policing, racial profiling, implicit bias, structural matters of historic injustice and the like. There’s plenty of theology and Bible, but there’s this good guidance into the latest literature and research and analysis.

And it goes a little deeper than some books by inviting us into conversation, guiding us on how to have heart-to-heart talks with others in generative, redemptive ways.

Lastly, one of the ways AOS goes a bit deeper is how it helps us grapple with what is called white privilege. Some may react to this phrase, but I beg you to hear him out. He offers some remarkable data and insight from good studies and helpful social critics that show us how this works.

One of the very helpful insights comes in a few pages about what multicultural educator Robin DiAngelo has termed “white fragility.” (Why do some folks seem to be nearly unable to handle tense conversations about race; why is there so much indignation when this stuff comes up? I’ve noticed that some people are more angry about any slightly overstated accusation of racism than real, brutal, racial violence. What is going on here with this intense defensiveness?)

I found this section really helpful, and I am still pondering it. We all have heard the phrase white privilege and while the book doesn’t dwell on this, it’s insights and suggestions are valuable. In setting the stage for thinking about white privilege, Wallis writes that we:

… simply have to admit that the experience of people of color is very different from the experience of white people. White people tend to see racism as an individual issue, about good and bad behavior by moral or immoral people. And because most white people don’t think we are “bad” or “immoral” and certainly not deliberately “racist,” racism can’t be applied to us. As I said above, “I am not a racist” is a regular response in the white community, either expressed or strongly felt. And defensiveness is a common reaction, as opposed to trying to really hear what black coworkers or fellow citizens are saying.

This section includes some vital theological contributions and calls us to expose idols that may be operative. He parses what is commonly meant by supremacy and privilege, naturally doing a bit of a history lesson. And this matter doesn’t just effect black and white relations in American, but the dominant culture’s relationships to Native people and, of course, to immigrants. Ugly stuff keeps happening — I learned of a hurtful episode just this morning — and we dare not pretend otherwise. By drawing on some helpful sociology (helping us understand “where white privilege comes from”) and how different cultures construe and construct the social realities of race and difference, we can begin to see aspects of this matter than we perhaps didn’t see before. Like a fish knowing it is in water, it isn’t easy. This chapter helps us gain new insight and then make commitments to stand against radicalized systems and structures. As Wallis puts it, citing the radical Pentecostal leader of ESA (Evangelicals for Social Action), Paul Alexander, “we can no longer ‘indulge in the luxury of obliviousness’ to implicit bias and the embedded history of white privilege.”

Like I said, this book is a bit deeper than some.

And reading it will be a fascinating learning experience, a good ride, especially if done with others. We invite you to take advantage of this limited time offer of half-off for an order of at least 20 copies.

Wallis asks if we are “a segregated church or a beloved community”? He asks us how we are doing in the Christian practice of “welcoming the stranger.”

In one inspiring chapter near the end he talks about “crossing the bridge to a new America.” The cover of the book has historic photo of folks crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, that bridge named after a Confederate general who became a Grand Dragon in the Ku Klux Klan. If you know your

In one inspiring chapter near the end he talks about “crossing the bridge to a new America.” The cover of the book has historic photo of folks crossing the Edmund Pettus Bridge, that bridge named after a Confederate general who became a Grand Dragon in the Ku Klux Klan. If you know your  history, or if you say the excellent, award winning film, Selma, with David Oyelowo, you know that that infamous bridge was “a powerful and threatening symbol of white power and supremacy in Selma Alabama.”

history, or if you say the excellent, award winning film, Selma, with David Oyelowo, you know that that infamous bridge was “a powerful and threatening symbol of white power and supremacy in Selma Alabama.”

Mr. Wallis was there on Saturday, March 7, 2015 for the fiftieth anniversary of that “Bloody Sunday”and his few pages on that are beautiful. He met a woman there who asked if he had seen the movie The Help and she talked about her own grandmother making 25 cents per day. She was a teen during the Montgomery bus boycott and they talked about that. Wallis, of course, knows Rep. John Lewis (who had been beat very badly on the bridge that day fifty years earlier) and they got to chat. Of course, Wallis shares some of President Obama’s speech that day — including a wonderful line that “America is not yet finished.” The whole telling is fascinating and makes a great, inspired ending to a challenging, illuminating and important book.

Thanks to Baker Publishing Group and Brazos Press for allowing this limited time half off deal. We are glad to particpate and will be happy to rush to you your order, at the extra discounts.

We will happily send out any other orders of any other books mentioned here at a 20% off.

TO ORDER BOOKS:

Brazos Press

DISCOUNT

America’s Original Sin

50% off

Must order at least 20 copies to qualify.

Smaller quantities, or any other book mentioned — 20% off.

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333