Thanks to those who read and even shared our Labor Day BookNotes that described a few recent books on faith and the work-world. We listed a compilation to past columns that we  did on this topic and I’m sure if you click through on those you will learn about books you haven’t heard of, religious ones and more general ones. There are so many resources to help us think about our careers and callings, the good and bad of our working lives. And new ones keep coming – for instance, any day now we’ll have the long-awaited Working in the Presence of God: Spiritual Practices for Everyday Work by Denise Daniels & Shannon Vanderwarker (Hendrickson; $24.95.) If you missed that column, skim back to our past BookNotes and check out those links. You won’t want to miss that James Taylor video!

did on this topic and I’m sure if you click through on those you will learn about books you haven’t heard of, religious ones and more general ones. There are so many resources to help us think about our careers and callings, the good and bad of our working lives. And new ones keep coming – for instance, any day now we’ll have the long-awaited Working in the Presence of God: Spiritual Practices for Everyday Work by Denise Daniels & Shannon Vanderwarker (Hendrickson; $24.95.) If you missed that column, skim back to our past BookNotes and check out those links. You won’t want to miss that James Taylor video!

In that column I mentioned Tom Nelson and his “Made to Flourish” network.

They have a simulcast (A Church for Monday) coming up October 5th – it would be a great way to enter or learn more about this conversation, this aspect of ministry. Learn more about it here.

One of the books that Tom Nelson wrote that I didn’t mention the other day is a helpful guide to thinking about the economic development and consequences of the work world. In The Economics of Neighborly Love: Investing in Your Community’s Compassion and Capacity (IVP; $18.00.) he makes clear that people of faith should always be thinking about how we can help our regions flourish; supporting good businesses and even being entrepreneurial can be ways to serve our neighbors. Voting in the marketplace (that is, the decisions we make as to we chose to spend our dollars) has consequences, often significant ones. (Tom doesn’t address it, precisely, but this is one of the big criticisms of mega-size and placeless entities like Amazon, who drain money from local economies and get out of paying taxes, even as they hurt local businesses and services. Data shows that wherever Amazon moves in, the wealth flows away from the local community, especially when municipalities and states give them huge tax incentives; I support them with my tax dollars and then they announce they want to put me out of business. Yep.) More can be said about community development and what “neighbor love” means for our stewardly, home-making economics, but this book by Tom Nelson is a nice start, recommended for anyone who hasn’t read this sort of thing.

One of the books that Tom Nelson wrote that I didn’t mention the other day is a helpful guide to thinking about the economic development and consequences of the work world. In The Economics of Neighborly Love: Investing in Your Community’s Compassion and Capacity (IVP; $18.00.) he makes clear that people of faith should always be thinking about how we can help our regions flourish; supporting good businesses and even being entrepreneurial can be ways to serve our neighbors. Voting in the marketplace (that is, the decisions we make as to we chose to spend our dollars) has consequences, often significant ones. (Tom doesn’t address it, precisely, but this is one of the big criticisms of mega-size and placeless entities like Amazon, who drain money from local economies and get out of paying taxes, even as they hurt local businesses and services. Data shows that wherever Amazon moves in, the wealth flows away from the local community, especially when municipalities and states give them huge tax incentives; I support them with my tax dollars and then they announce they want to put me out of business. Yep.) More can be said about community development and what “neighbor love” means for our stewardly, home-making economics, but this book by Tom Nelson is a nice start, recommended for anyone who hasn’t read this sort of thing.

Another great, great book (that was reviewed in greater detail in one of those older links I shared to past BookNotes) that addresses this and, no doubt, influenced Nelson in his own Economics… book is the magisterial Kingdom Callings: Vocational Stewardship for the Common Good (IVP; $22.00.) by Amy Sherman. In that book she makes a powerful case (based on Proverbs 11:10) that even the poor and marginalized will rejoice in the success of a just business; truly righteous, just businesses make things better, even for the poor. So she invites us to think faithfully about stewarding our vocational aspirations in ways that not only please us or help us find our own professional sweet spot but in ways that serve the common good. She offers several different styles or “levels” of involvement showing numerous ways (from the simplest to the most sophisticated) that our work lives impact and serve the world.

Another great, great book (that was reviewed in greater detail in one of those older links I shared to past BookNotes) that addresses this and, no doubt, influenced Nelson in his own Economics… book is the magisterial Kingdom Callings: Vocational Stewardship for the Common Good (IVP; $22.00.) by Amy Sherman. In that book she makes a powerful case (based on Proverbs 11:10) that even the poor and marginalized will rejoice in the success of a just business; truly righteous, just businesses make things better, even for the poor. So she invites us to think faithfully about stewarding our vocational aspirations in ways that not only please us or help us find our own professional sweet spot but in ways that serve the common good. She offers several different styles or “levels” of involvement showing numerous ways (from the simplest to the most sophisticated) that our work lives impact and serve the world.

I don’t know if you hear about this stuff at your church, but it seems to us that any wise missional vision will include this fairly ordinary (but extraordinarily interesting and challenging) task of helping each other think about faith in the marketplace. Start with Sherman’s call to “steward our vocational aspirations” and see how it leads to, as Nelson puts it, “the economics of neighborly love.”

Which leads me to the theme of this BookNotes column.

It is good for us mostly middle class folks to talk about serving God in our work-a-day lives. What else can we do? Christ as Lord calls us to honor His rule over “every square inch” of our lives, so obviously we must thinking religiously about our jobs, our callings, our employment, and occupations.

But we must be aware of the fact that for many, talking about such things – being a Christian in the business sector, seeing the relationship of faith in the sciences, thinking about education from a Christian perspective, wondering about how to be a faithful follower of Jesus in health care or media or computer science or management – is a luxury. Most people in the world are poor; even these days in our country, many are unemployed; here and abroad, children are starving. And are all, as Steve Garber reminds us in Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good, we are all implicated. We are part of the broken, broken world that God so loves.

Ronald Sider’s Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger (Thomas Nelson; $15.99) remains a must-read to explore and motivate us to care about the poor; it is surely one of the most important books of the last 50 years. The best-selling The Hole in Our Gospel: What Does God Expect of Us? The Answer That Changed My Life and Might Just Change the World by Richard Stearns came out ten years ago this month, and we have a brand new, 10th Anniversary Edition (Thomas Nelson; $17.99) His story of finding meaning by shifting away from his successful big business career to take up more directly the cries of the poor important and inspiring reading for all of us.

Ronald Sider’s Rich Christians in an Age of Hunger (Thomas Nelson; $15.99) remains a must-read to explore and motivate us to care about the poor; it is surely one of the most important books of the last 50 years. The best-selling The Hole in Our Gospel: What Does God Expect of Us? The Answer That Changed My Life and Might Just Change the World by Richard Stearns came out ten years ago this month, and we have a brand new, 10th Anniversary Edition (Thomas Nelson; $17.99) His story of finding meaning by shifting away from his successful big business career to take up more directly the cries of the poor important and inspiring reading for all of us.

HERE ARE TWO NEW EXCELLENT BOOKS ON HUNGER & POVERTY and a few others on justice work…

Silence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and Make Our Economy Work for Everyone Arthur Simon (Eerdmans) $29.00 Does our apathy or even our silence really indict us? Can silence really kill? It is a strong accusation and Art Simon is careful to explain why. This book is the most important and comprehensive faith-based study of poverty and hunger (in the US and abroad) in ages; Art has written some wonderful books in the past but this may be his magnum opus. In it, he deftly explores the complications and controversies around poverty and public policies that might fruitfully address the crisis of hunger. Although trained as a Lutheran pastor, he has spent most of his adult life organizing citizens to lobby –through the organization he founded, Bread for the World – for legislation that helps the poor, so much of our political legislation has direct consequence (sometimes for good, sometimes for ill) on the impoverished. Maybe you’ve heard the story – Art and other Bread for the World leaders tell it often – of how one year, in one quick vote in the Reagan years, US Congress cut more from life-saving foreign aid than all the charities of all the US churches combined had given that year. I forget the exact figures, but imagine if all the churches, together, raise and generously share 10 million dollars for relief. And imagine that the government cuts $100 million from our aid budget. For those that truly want to save lives and bring relief to starving brothers and sisters in Africa, say, might it have been better to spend more time letting our congressional representatives know that we favor such aid? If we love our neighbors by sincerely donating to charities, why are we silent when so much more is cut?

Silence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and Make Our Economy Work for Everyone Arthur Simon (Eerdmans) $29.00 Does our apathy or even our silence really indict us? Can silence really kill? It is a strong accusation and Art Simon is careful to explain why. This book is the most important and comprehensive faith-based study of poverty and hunger (in the US and abroad) in ages; Art has written some wonderful books in the past but this may be his magnum opus. In it, he deftly explores the complications and controversies around poverty and public policies that might fruitfully address the crisis of hunger. Although trained as a Lutheran pastor, he has spent most of his adult life organizing citizens to lobby –through the organization he founded, Bread for the World – for legislation that helps the poor, so much of our political legislation has direct consequence (sometimes for good, sometimes for ill) on the impoverished. Maybe you’ve heard the story – Art and other Bread for the World leaders tell it often – of how one year, in one quick vote in the Reagan years, US Congress cut more from life-saving foreign aid than all the charities of all the US churches combined had given that year. I forget the exact figures, but imagine if all the churches, together, raise and generously share 10 million dollars for relief. And imagine that the government cuts $100 million from our aid budget. For those that truly want to save lives and bring relief to starving brothers and sisters in Africa, say, might it have been better to spend more time letting our congressional representatives know that we favor such aid? If we love our neighbors by sincerely donating to charities, why are we silent when so much more is cut?

So Bread for the World helps citizens who are willing, inspired by their Biblical faith, to pay attention to the sometimes obscure (but oh-so-significant) legislation battles brewing in Congress, or even in Congressional committees. Sometimes just a few House Representatives or Senators can prevent a bill from even being voted on, so even a few letters to a few leaders or one or two letters to the editor in the paper can make a difference!) This is true in legislation regarding international aid and global concerns as well as for domestic concerns affecting those in poverty here. From TANF funding or SNAP reform to clean water proposals or the significance of the much-discussed Farm Bill, Mr. Simon knows more than almost anyone, drawing on experts from across the ideological spectrum and nurturing friendships in think-tanks, philanthropies, front line relief agencies, among third world church leaders, in small town church-based food programs, and dysfunctional urban school systems; he has listened and learned and advocated (building bipartisan teams) for decade after decade about how to reduce poverty and end hunger.

And he has learned to be savvy and wise; nobody wants to “throw money” at a problem or squander limited revenues and he knows the strengths and weaknesses of the critiques made against foreign aid and US entitlement programs. When Art Simon and his BFW movement leaders invite church folk to get behind a certain piece of legislation you can be assured they have studied it from a variety of perspectives and have held consultations with theological scholars and policy wonks and anti-poverty activists from here and abroad. As this book documents, they know what they are doing.

You may recall the movie Schindler’s List about the German businessman that tirelessly shuttled Jews out of Nazi-occupied Poland. He increasingly put his time and money and life at risk to save just one more family. He is rightly held up as a hero, an example of the “righteous Gentiles” who rescued Jews who were being lead to the slaughter.

When I think of heroes like Schindler, I think of Art Simon. It may be that he has saved more people from unjust death than anyone living today. This is not hyperbole — give the guy a Nobel Peace Prize already! Read Silence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and you’ll learn much and you will be impressed by Simon’s extraordinary life, about which he writes humbly.

When I think of heroes like Schindler, I think of Art Simon. It may be that he has saved more people from unjust death than anyone living today. This is not hyperbole — give the guy a Nobel Peace Prize already! Read Silence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and you’ll learn much and you will be impressed by Simon’s extraordinary life, about which he writes humbly.

As you will learn, briefly, it all started in the early 70s while a pastor of a small urban parish in New York City. Pastor Simon realized that although several churches were doing food pantries and offering immediate assistance for the neediest, include those ground down by poverty and racism and slumlords in his own parish, so many of the causes and so many of the answers to systemic poverty and hunger was structural, most with a political dimension. Which is to say, food pantries were not enough: restoring justice and flourishing was a matter of public policy and legislation. (The Bible has said this all along, of course, with the clear policy mandates in the Old Testament law that give the poor a fair second change, and holy warnings like, “Woe to those who pass bad laws that crush the poor” which you know if you’ve ever got far into the book of Isaiah.

That is, a simple vote in Congress to support a life-giving policy can literally change lives, even save lives. (Just think of the fair housing legislation or of the early legislation about child labor or the impeccably documented value of Food Stamps and the perennial congressional battles about funding; or more globally, the huge questions of foreign aid, how our aid is sometimes tied to our military support for corrupt dictators that refuse land reform or ways in which global banking legislation through the World Bank or the IMF ripples consequences to developing economics from South America to South Africa, from East Timor to East Asia.)

So, as we’ve said, Mr. Simon and some other church folks started what they imagined to be a faith-anchored citizen’s lobby. They would get church folks to actually vote – this was before the rise of the Christian right when voting against homosexual rights or for pro-life issues became part of the identity of many conservative evangelicals – inspired by what would best serve their poorer brothers and sisters. They would be invited to lobby as politically engaged Good Samaritans. Church folks would be called to unite around a seemingly non-controversial but overlooked piece of anti-hunger legislation, or some anti-poverty bill, or something about WIC, say. It grew to become a nation-wide movement, organized by church folks in each congressional district and Bread for the World was formed. BFW passed out no bread; it is not a relief or development organization. I invites Christian citizens to use their gift of citizenship to lobby their elected officials to vote in ways that reflect our desire to help the poor, to do justice, to create (insofar as government is able) a sustainable, healthy economy, and to prevent economic injustice while fostering solutions to poverty and hunger, here and abroad.

In other words they were inviting citizens to get busy doing the hard work of shift the conversation and passing legislative initiatives for the sake of the poor.

Art often tells the story about a British economist who had met (in the early 1970s) with the Vatican, where Catholic leaders were calling on religious folks to step up their advocacy around world hunger concerns. Barbara Ward seemed enthused as she talked with a US Senator, suggesting that any day his office would be flooded by calls from the faithful, showing citizen support for a certain anti-hunger bill. The Senator said “I’ll call you when I get the first call.” Later, the Senator reported to Art that “I never had to make that call.” That is, nobody contacted his office, and the legislation – as it sometimes does – dies of atrophy, of apathy; our elected officials aren’t going to go to the mat on an issue they don’t think anybody cares about and since most citizens only call about stuff that peeves them, personally, the bigger issues of reforming unjust economic policies or offering aid to the poor often languish. The squeaky wheel gets the grease, they sometimes say, and this is a truism in citizen political action: a few calls from ordinary folks supporting this or that bill or resolution, can make a huge difference as Congressional aids sit up and take notice when they start hearing from constituents about a certain obscure bill about food or water or foreign aid or school lunch programs. We can make a difference. And conversely, our silence can kill.

Art’s many years at the helm of Bread for the World brought him into conversation with anti-hunger scholars, front line folk doing work in refugee camps and in well-digging programs and girls schools in the Third World. He learned what works and is the first to admit that government and policy cannot solve all the problems of poverty. However – as this book shows — very many of the injustices of global (and domestic) poverty are connected to big picture, systemic matters. The realities of war and climate change, the legacy of colonialism, old and new racism, practices such as government subsides of cash crops exporting wealth, arcane details of tariffs and trade agreements, immigration law, bad faith in dangerous technologies, naïve hopes, corrupt legislators and leaders, the undue influence of self-interested agribusiness lobbyists, and what educational visions governments support, all come to play to create a better or worse economy.

The right bill (alone) cannot change the world but an increase in certain kinds of aid administered in directed ways can save lives. Years ago BFW speculated (based on their own research about how many letters and calls to Congress it took to get a certain piece of foreign aid legislation passed) that each person who wrote a letter saved thousands of lives. Sure you should continue to support your Compassion or World Vision child. But being involved with Bread for the World will magnify your life-saving influence and incarnate your compassion one hundred fold!

After Art retired from Bread for the World, another extraordinary Lutheran leader, David Beckman, took the helm (after a time working at the World Bank where he lead Bible studies with global leaders.) Beckman wrote a short and really useful little book called Exodus From Hunger: We Are Called to Change the Politics of Hunger (WJK; $18.00) that tells the BFW story in the 21st century; it, too, is very highly recommended.

After Art retired from Bread for the World, another extraordinary Lutheran leader, David Beckman, took the helm (after a time working at the World Bank where he lead Bible studies with global leaders.) Beckman wrote a short and really useful little book called Exodus From Hunger: We Are Called to Change the Politics of Hunger (WJK; $18.00) that tells the BFW story in the 21st century; it, too, is very highly recommended.

The new Silence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and Make Our Economy Work for Everyone, though, is amazingly comprehensive and a must-have resource for anyone seriously engaged in this work. It is, in a way, the fruit of Art Simon’s decades of living and learning in the midst of this amazing, complex, fascinating, dramatic story of making strides to reform our economies.

It seems to me that if you care about this topic, it will be a great handbook to school you in more of what you need to understand. (And, frankly, as the Presidential primaries are heating up, and there are more debates about economics and taxes and tariffs and welfare and charts and statistics, this would be a useful primer to help you sort out much of the contested claims and counter-claims.)

It also seems to me that if you have read some of the criticisms about the corruption and waste in government-based foreign aid programs and are a bit skeptical of this whole project, it is worth reading this for a fair-minded, evidence-based view. Agree or not with everything Art concludes, it is an exceptionally useful contribution to the discussions about all this and you will be better informed to make up your own mind.

I’m not going to lie: there are some (nicely explained) details about the percentages of aid the US actually gives, about complicated economic theories, about wealth and wage differences, about the injustices we hear about. There are a few charts. He is making a case for what he thinks are wise and helpful solutions and to do that he has to dive a bit deep.

He explains what government can and should do. As we’ve said, charities alone cannot solve these complex big-picture problems. Although ideologues on the right end of the partisan spectrum insist that it’s mostly the private sector’s task, almost everyone on the front lines of global poverty relief or who work with the poor in the US say otherwise; they all see and experience the limits of charity and the need for appropriate governmental action. (President Reagan was just wrong when he said, simplistically, “government is the problem.”) So Art explains all this with data and stats and footnotes that are themselves an education, explaining (thanks be to God) the complexities of dense scholars like Thomas Piketty and other Nobel Prize winning economists, wading into questions about wealthy creation, the implications of the national debt, etc. etc. etc.

Years ago a Dutch economist and Reformed Christian leader in the old Kuyper party in Holland, Bob Goudzwaard, wrote a book about the idols of our age. (It was later updated and expanded with two other authors as Hope in Troubled Times: A New Vision for Confronting Global Crisis (Baker Academic; $24.00) and, upon reading it, Brian McLaren was inspired to write Everything Must Change: When the World’s Biggest Problems and Jesus’ Good News Collide (Thomas Nelson; $14.99) that explored the ideologies and philosophies and assumptions about society and culture and government and meaning and values that propel our idolatrous cultures. Goudzwaard’s rather dense book and McLaren’s lively interpretation of it are both excellent and I recommend them for those wanting to see the way big issues (from poverty to environmental degradation to militarism) combine and are driven by certain spirits or ideologies.

Years ago a Dutch economist and Reformed Christian leader in the old Kuyper party in Holland, Bob Goudzwaard, wrote a book about the idols of our age. (It was later updated and expanded with two other authors as Hope in Troubled Times: A New Vision for Confronting Global Crisis (Baker Academic; $24.00) and, upon reading it, Brian McLaren was inspired to write Everything Must Change: When the World’s Biggest Problems and Jesus’ Good News Collide (Thomas Nelson; $14.99) that explored the ideologies and philosophies and assumptions about society and culture and government and meaning and values that propel our idolatrous cultures. Goudzwaard’s rather dense book and McLaren’s lively interpretation of it are both excellent and I recommend them for those wanting to see the way big issues (from poverty to environmental degradation to militarism) combine and are driven by certain spirits or ideologies.

Arthur Simon doesn’t tackle many of the philosophical assumptions pushing our cultures and economies, but his insights will take us a long way towards asking the right questions about this unavoidable, central part of our lives. His data and insights really to get us “under the surface” and force us to reflect, even as we are equipped to act. If we are to be like the “sons of Issachar” in 1 Chronicles 12:32 and understand the times, and “keep ourselves from idols” (1 John 5:21) we must be aware of these spirits of the age, the idols of progress and growth and materialism behind standard-fare capitalism.

(Just the other day a conservative journal that I read did a book review about some books about economics and celebrated the “engines of progress” in ways that assumed, without question, that growth is good, that driving towards bigger and bigger is the essential meaning of healthy economics, an assumption behind both the right and the left, by the way; both who ought to know better, that “progress” is more than economic growth. (Yeah, tell that to the child of rich parents who are getting a divorce, that they are experiencing “progress” by getting their nicer house, even if their family is demolished. Try telling them that those singular “engines of progress” were a blessing and not a curse.)

Goudzwaard called this “reductionism”– where we reduce the multi-dimensional development of human and cultural flourishing to just one thing: money. As we all know, when we elevate money to that height, asking it to bear that sort of idolatrous weight, it is called Mammon. Art Simon himself did a beautiful, thoughtful book on this a few years back, for personal reflection  and it is as potent now as it was then. It is called How Much Is Enough?: Hungering for

and it is as potent now as it was then. It is called How Much Is Enough?: Hungering for  God in an Affluent Culture (Baker; $16.00.) For a comprehensive study of all the key passages about money/Mammon in the Bible see the hefty Money and Possessions (in the Interpretation series) by Walter Brueggemann (WJL; $40.00.) For a more practical and delightfully well-balanced study of how all this might inform our daily financial habits, see Practicing the King’s Economy: Honoring Jesus in How We Work, Earn, Spend, Save, and Give by Michael Rhodes, Robby Holt and Brian Fikkert (Baker Books; $19.99.) It is very, very useful, balanced, thoughtful, wise.

God in an Affluent Culture (Baker; $16.00.) For a comprehensive study of all the key passages about money/Mammon in the Bible see the hefty Money and Possessions (in the Interpretation series) by Walter Brueggemann (WJL; $40.00.) For a more practical and delightfully well-balanced study of how all this might inform our daily financial habits, see Practicing the King’s Economy: Honoring Jesus in How We Work, Earn, Spend, Save, and Give by Michael Rhodes, Robby Holt and Brian Fikkert (Baker Books; $19.99.) It is very, very useful, balanced, thoughtful, wise.

Mr. Simon is aware of these deep theological questions about economics but he’s an activist, wanting to save lives through marshaling political will to achieve sensible ends. He wants evidence based reforms and he’s listened and learned and here interprets for us a way forward towards how to change the world in helpful ways.

One of the ways this vital book is helpful is its reminder that reducing the gross tragedies of starvation and hunger and poverty is a moral matter that could unite us beyond our partisan divides. As Senator Bob Dole writes on the back cover “ Silence Can Kill makes a credible case that ending hunger is a surprisingly attainable goal.” It offers a hopeful, healing vision and it’s an issue most of us would agree is important. The question is if we are willing to learn, to become empowered to use our voices, to speak up. This book by this fine gentleman will help.

Tucked away in a small footnote is a hint to how it is that Rev. Simon learned to speak up and get involved. In the book he is exploring some of the related matters in the constellation of issues that affect the poor, that contribute to the causes of poverty. He tells about the legacy of racism in our culture and, without much drama – Simon is never flamboyant or breathy – quietly tells of the sudden and unfair internment of our Japanese citizens during World War II and how his father protested. Simon writes:

On the spot in Eugene where many were taken away on short notice with only what they could carry, a memorial to those citizens includes a stone with my father’s name and the inscription: Martin P. Simon. He spoke in protest. His courage inspired others.” My brother and I were among the “others.”

Perhaps this story will remind you of the legacy we leave among those who watch our lives, even our children and grandchildren. Will you be known as one who speaks up for the poor and oppressed? Will you consider doing the sort of civic work that BFW calls us to, leveraging our citizenship for others? Will you commit to reading Silence Can Kill?

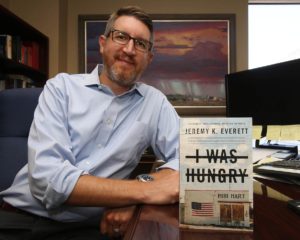

I Was Hungry: Cultivating Common Ground to End An American Crisis Jeremy K. Everett (Brazos Press) $16.99 What a blessing to have a second major book released this season within the religious publishing world – kudos to Brazos Press for taking up this terrific, exciting read by a young-ish activist, founder of the Texas Hunger Initiative. Informed by the framework and inspiration of Bread for the World and other faith-based public policy initiatives, Jeremy Everett (a graduate of Baylor University and Truett Theological Seminary) has spent years as an advocate for the poor. From an inspiring story of being moved to give away his stuff to the homeless after watching the Saint Francis film Brother Son, Sister Moon to the riveting opening pages about running a special needs medical shelter for hundreds of evacuated folk in the immediately aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, we learn that Everett has a big heart and has learned, often the hard way, what it means to not only be proximate with the poor and hurting, but how to organize social services in ways that help stem the tide of human anguish. He’s colorful and dedicated and, I gather, not only winsome but seemingly unstoppable. I suppose one has to be if one is doing serious research to learn the facts and doing on-the-ground, directly care giving and energetic advocacy for the poor. His community organizing skills become evident early on in this page-turner of a book. I Was Hungry – notice the way the words are crossed out in the art design of the book – is a wild, hopeful read!

I Was Hungry: Cultivating Common Ground to End An American Crisis Jeremy K. Everett (Brazos Press) $16.99 What a blessing to have a second major book released this season within the religious publishing world – kudos to Brazos Press for taking up this terrific, exciting read by a young-ish activist, founder of the Texas Hunger Initiative. Informed by the framework and inspiration of Bread for the World and other faith-based public policy initiatives, Jeremy Everett (a graduate of Baylor University and Truett Theological Seminary) has spent years as an advocate for the poor. From an inspiring story of being moved to give away his stuff to the homeless after watching the Saint Francis film Brother Son, Sister Moon to the riveting opening pages about running a special needs medical shelter for hundreds of evacuated folk in the immediately aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, we learn that Everett has a big heart and has learned, often the hard way, what it means to not only be proximate with the poor and hurting, but how to organize social services in ways that help stem the tide of human anguish. He’s colorful and dedicated and, I gather, not only winsome but seemingly unstoppable. I suppose one has to be if one is doing serious research to learn the facts and doing on-the-ground, directly care giving and energetic advocacy for the poor. His community organizing skills become evident early on in this page-turner of a book. I Was Hungry – notice the way the words are crossed out in the art design of the book – is a wild, hopeful read!

What other book makes the Consumer Price Index and discussions about SNAP interesting, and playfully calls Father Gustavo Gutierrez, the father of liberation theologians, a “Peruvian Yoda” and tells about singing happy birthday to him at a Southern Baptist preacher’s home? Or tells a story of inviting gang members who had broken in to their community coffee shop to a re-opening celebration, showing how “love wins” can be more than a slogan, but a business practice?

In fact, Bread for the World President David Beckman (who has read and written tons on this topic) writes in a moving foreword, “Once I started the first chapter of this book, I had a hard time putting it down. Jeremy Everett is a great storyteller. And the overarching story of this book is God’s call to Jeremy – to all of us actually – to end hunger.”

In fact, Bread for the World President David Beckman (who has read and written tons on this topic) writes in a moving foreword, “Once I started the first chapter of this book, I had a hard time putting it down. Jeremy Everett is a great storyteller. And the overarching story of this book is God’s call to Jeremy – to all of us actually – to end hunger.”

After his early episodes of giving away his stuff inspired by St. Francis, and his eventual entry into the worlds of poverty and dislocation, homelessness and abuse, Everett tells us about his years working in community-based organizing. He introduces us to people he knows – giving essential faces and back-stories to fellow-citizens who struggle with what some call “food insecurity.” Unlike some in utter starvation in Sub Saharan Africa, say, or the malnourished in Haiti or Chad, there are many in the US who simply don’t know if they will have enough to eat, especially for the working poor, between paychecks. Economic injustice and policy questions are complicated – as we’ve learned from Art Simon’s book, Silence Kills. I Was Hungry dives in to some of this, too (although with an exclusive focus on domestic, and often rural or small town poverty.)

Everett’s Texas Hunger Initiative is an organization that partners with the United States Department of Agriculture, Texas state agencies, the corporate sector, and thousands of churches and community-based organizations. When he says in the subtitle that this book is for “cultivating common ground to end an American crisis” he knows what he’s talking about. I’d say you might read it just to learn about his adept navigation of various social sectors, non-profits and governmental agencies, to advance social entrepreneurship, uniting different kinds of folks to accomplish this good, lasting work.

Everett’s Texas Hunger Initiative is an organization that partners with the United States Department of Agriculture, Texas state agencies, the corporate sector, and thousands of churches and community-based organizations. When he says in the subtitle that this book is for “cultivating common ground to end an American crisis” he knows what he’s talking about. I’d say you might read it just to learn about his adept navigation of various social sectors, non-profits and governmental agencies, to advance social entrepreneurship, uniting different kinds of folks to accomplish this good, lasting work.

I like that as he tells the story of the organization’s history he tells stories of its work with communities “from West Texas to Washington DC” and — get this! – “helping Christians of all political persuasions understand how they can work together to truly make a difference.” I like that he talks about building trust. It seems to me that he is right: if we are going to eradicate hunger and work well on helping stop poverty and food insecurity (or any other pressing social issue) we are going to need everybody involved. Our civic infrastructures and local friendships are going to have to become more bi-partisan. We are going to have to learn to trust each other and work together.

So there’s that.

In fact, Everett has a chapter on politics called “Searching for Consensus amid a Landscape of Contention.” There are some brilliant stories and essential lessons learned.

One story is about how, due to state budget cuts, regional offices were closed that had been the places for poorer folks to go to sign up for benefits (like SNAP, which we used to call “Food Stamps.”) This proved a hardship on many, many people and the Texas Hunger Imitative partnered with the State government to retool delivery platforms and venues. Talk about caring about the common good, about wise and savvy faith-based partnerships working well with big governmental bureaucracies. Alas, that story doesn’t end there and there is another chapter of the story about justice advocacy groups waging a campaign which ended up demonizing conservatives who disagree with a certain plan about serving refugees. It gets ugly and counterproductive.

Everett explains,

Just like the group fighting the golf course in San Antonio, this group was on the right side of justice, but their tactics proved to be not only unpersuasive but also damaging to the communities they served.

He continues,

State leaders were outraged by the public shaming and looked into the organization behind it. When they found the organization had a contract with the state and was playing a leadership role in providing the poor with federal benefits access, the state leaders attempted to end the program. When that did not work – because it was legislatively created – they cancelled the contract with the P3 consortium and slowly strangled the initiative until it failed to exist.

Granted, that is sometimes how the big boys of the far right work, deliberately hurting agencies that serve the poor. I’ve seen it, and this is not an exaggeration.

However, Everett’s take-away is golden:

…the tactic of shaming the powerful didn’t just fail to change the minds of the powerful, it also motivate them to look for ways to hurt those opposing their interests. Once again, the shared-power approach proved to be life-giving – generating the model to increase access, nutrition, health – and the shaming-power approach proved to be life-taking. When we are operating on a state or federal level, politics can be catastrophic when we get it wrong. Demonizing those who we are trying to persuade does not work.

The rest of the chapter will be worth the price of the book for some of us, I think. He reminds us about shared power, about building consensus, about common ground. He reminds us that we are all made in the image of God and we dare not hurl insults against even those with whom we disagree. Collaboration and finding common ground is not easy, but we must “honor the createdness of the other.” We want to “move the world toward just, toward shalom” so our “tactics and strategies must reflect the integrity we hope to achieve for our cause.”

His story of the slow change of the heart of a congressman, a Christian, who gradually learned more about the realities of poverty in his district brought tears to my eyes. I know a congressman like that, a leader with whom I had regular political disagreements. Praying together in his home about how his party’s policies were causing great harm in Central America is a memory I’ll never forget, regardless of how he ended up voting on that particular foreign policy bill. I so love that Everett doesn’t want to throw anybody under the bus on the way towards the beloved community.

This short book is an excellent primer on anti-hunger activism, on the questions of poverty that plague these United States. It is faith-infused, but civic minded, pushing for good goals in good ways. It is a prefect companion to Silence Can Kill by Arthur Simon. We have purchased a lot of these for our little store and hope many folks pick it up. It would make a great small group study or book club title.

AND A FEW MORE…

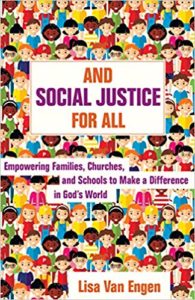

And Social Justice for All: Empowering Families, Churches, and Schools to Make a Difference in God’s World Lisa Van Engen (Kregal) $13.99 This is an excellent resource, more than 300 pages, with information and insight about a dozen different topics — from creation care to human trafficking, from fair-trade wisdom to disabilities rights, from racial justice concerns to family care. There’s stuff about bearing the “fierce light” of being a change-maker and guides on creating a community gathering. There’s even a plan to raise awareness, topic by topic, month by month, which looks intriguing to try. This evangelical educator and mom from Holland, Michigan, has given us a rare combination of gospel-centered faith and down-to-Earth education for social change. She and her family are members of Covenant CRC in St. Catharines, Ontario. Highly recommended.

And Social Justice for All: Empowering Families, Churches, and Schools to Make a Difference in God’s World Lisa Van Engen (Kregal) $13.99 This is an excellent resource, more than 300 pages, with information and insight about a dozen different topics — from creation care to human trafficking, from fair-trade wisdom to disabilities rights, from racial justice concerns to family care. There’s stuff about bearing the “fierce light” of being a change-maker and guides on creating a community gathering. There’s even a plan to raise awareness, topic by topic, month by month, which looks intriguing to try. This evangelical educator and mom from Holland, Michigan, has given us a rare combination of gospel-centered faith and down-to-Earth education for social change. She and her family are members of Covenant CRC in St. Catharines, Ontario. Highly recommended.

Loving God and Neighbor with Samuel Pierce Michael A.G. Haykin & Jerry Slate (Lexham Press) $12.99 This is the second in a little series called “Lived Theology.” (I will be writing more about the other, an introduction to the public engagement theology of Abraham Kuyper, also in this little series.) Those that know much about evangelical missionary work may know the name of Samuel Pierce, a nearly forgotten saint who embodied a late eighteenth-century Baptist piety and advanced a wholistic vision of the gospel. This handsome little book invites us to explore Pearce’s “holy love” and tells of his years of ministry in England (and his trip to India and preaching trip through Ireland.) Loving God and Neighbor models how older-school evangelical faith can propel one to care deeply about serving one’s neighbors and about caring about God’s world as an expression of a deep appreciation for the saving grace of Christ.

Loving God and Neighbor with Samuel Pierce Michael A.G. Haykin & Jerry Slate (Lexham Press) $12.99 This is the second in a little series called “Lived Theology.” (I will be writing more about the other, an introduction to the public engagement theology of Abraham Kuyper, also in this little series.) Those that know much about evangelical missionary work may know the name of Samuel Pierce, a nearly forgotten saint who embodied a late eighteenth-century Baptist piety and advanced a wholistic vision of the gospel. This handsome little book invites us to explore Pearce’s “holy love” and tells of his years of ministry in England (and his trip to India and preaching trip through Ireland.) Loving God and Neighbor models how older-school evangelical faith can propel one to care deeply about serving one’s neighbors and about caring about God’s world as an expression of a deep appreciation for the saving grace of Christ.

Missional Economics: Biblical Justice and Christian Formation Michael Barram (Eerdmans) $26.00 We have a pretty hefty economics section (besides our section of global development, world hunger, and international affairs.) Some are heady, some less so. Some are tough in their critique of mainstream capitalism, but some, like, say, Redeeming Capitalism by Kenneth Barnes, with a foreword by Miroslav Volf (Eerdmans; $25.99) are thoughtful, with a serious, moral center, but more balanced. We have extraordinary, serious works like Just Capitalism: A Christian Ethic of Economic Globalization by Brent Waters (WJK; $40.00) that seem very much like something neither right nor left, but seeking a deep, alternative vision. That is also why we’ve often recommended Completing Capitalism: Heal Business to Heal the World by Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub (Berrett-Koehler; $19.95) about their surprisingly good work with the Mars Corporation.

Missional Economics: Biblical Justice and Christian Formation Michael Barram (Eerdmans) $26.00 We have a pretty hefty economics section (besides our section of global development, world hunger, and international affairs.) Some are heady, some less so. Some are tough in their critique of mainstream capitalism, but some, like, say, Redeeming Capitalism by Kenneth Barnes, with a foreword by Miroslav Volf (Eerdmans; $25.99) are thoughtful, with a serious, moral center, but more balanced. We have extraordinary, serious works like Just Capitalism: A Christian Ethic of Economic Globalization by Brent Waters (WJK; $40.00) that seem very much like something neither right nor left, but seeking a deep, alternative vision. That is also why we’ve often recommended Completing Capitalism: Heal Business to Heal the World by Bruno Roche and Jay Jakub (Berrett-Koehler; $19.95) about their surprisingly good work with the Mars Corporation.

Steve Garber, who has worked with this team of authors, says,

With a rare willingness to ask the most critical questions about the nature of business, their ‘economics of mutuality’ is a vision for doing good and doing well in the context of one of the most iconic brands in the modern world. Neither charity nor corporate social responsibility, but rather a way for sustained profitability, Completing Capitalism argues for making money in a way that remembers the meaning of the marketplace.”

With so many good resources like this, it is hard to suggest just one, but these days, I’m inclined to most heartily recommend this Missional Economics for starters because it so helpfully explores the biblical material. It does not do everything a book on economics does, but it does what we Christian must have: a good study of the pertinent Biblical texts. This is a remarkable book, exceptionally helpful and vital.

Mark Labberton of Fuller Theological Seminary calls it, “a stunning gift.”

Our friend, New Testament scholar Michael Gorman, writes:

This readable but challenging book compellingly unpacks the Bible’s consistent focus on transforming the ways we think (and therefore act) about money, possessions, the poor, and more. The result is a desperately needed antidote to the consumerist, self-indulgent culture in which Western Christians live today. And it is also a persuasive invitation to participate in God’s loving care for a needy world.

The publisher says:

Barram searches for insight into God’s purposes for economic justice by exploring what it might look like to think and act in life-giving ways in the face of contemporary economic orthodoxies. The Bible repeatedly tells us how to treat the poor and marginalized, Barram says, and faithful Christians cannot but reflect carefully and concretely on such concerns.

Written in an accessible style, this biblically rooted study reflects years of research and teaching on social and economic justice in the Bible and will prove useful for lay readers, preachers, teachers, students, and scholars.

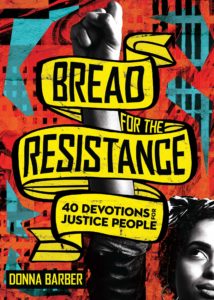

Bread for the Resistance: 40 Devotions for Justice People Donna Barber (IVP/The Voices Publishing) $15.00 We’ve written favorably about books by Leroy Barber and it is a delight to know of Donna, his wife and ministry partner, co-founder of The Voices Project which is trying to “influence culture through training and promoting leaders of color.” She is the director of Champions Academy, an initiative of the Portland Leadership Foundation and is the first African American to serve on her local district’s school board. This is just what you’d think, a feisty, visionary, inspiring set of devotional readings for justice activists. Are you tired or over-worked, struggling, wondering how to keep on keeping on? This will refresh your soul and keep you going. Brand new – we have it on our counter at the shop!

Bread for the Resistance: 40 Devotions for Justice People Donna Barber (IVP/The Voices Publishing) $15.00 We’ve written favorably about books by Leroy Barber and it is a delight to know of Donna, his wife and ministry partner, co-founder of The Voices Project which is trying to “influence culture through training and promoting leaders of color.” She is the director of Champions Academy, an initiative of the Portland Leadership Foundation and is the first African American to serve on her local district’s school board. This is just what you’d think, a feisty, visionary, inspiring set of devotional readings for justice activists. Are you tired or over-worked, struggling, wondering how to keep on keeping on? This will refresh your soul and keep you going. Brand new – we have it on our counter at the shop!

Rest for the Justice Seeking Soul: 90 Meditations Susan K. Williams Smith (Whitaker House) $14.99 FORTHCOMING – PRE-ORDER: due to be released November 12, 2019 Wow, this is another small collection of daily meditations by an experienced leader who is a woman of color, the communications director and secretary to the Board of Directors for the Samuel D. Proctor Ministers Conferences. Those who know the African American church know that the Samuel Proctor name is deeply esteemed and Ms. Smith’s connection there is indication of her stature. Perhaps more importantly, she’s known on the streets as a voice for faith-based social change; she has been involved in organizing in her home-town of Columbus, Ohio, and on the national level. She is involved with numerous social justice organizations, including Dr. William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign. These short readings were designed for those who are feeling beleaguered and battered down in their activism during these hard days. Kudos to Whitaker House (not known for these sorts of social action books) for taking up the writings of this important sister in the struggle. PRE-ORDER IT NOW.

Rest for the Justice Seeking Soul: 90 Meditations Susan K. Williams Smith (Whitaker House) $14.99 FORTHCOMING – PRE-ORDER: due to be released November 12, 2019 Wow, this is another small collection of daily meditations by an experienced leader who is a woman of color, the communications director and secretary to the Board of Directors for the Samuel D. Proctor Ministers Conferences. Those who know the African American church know that the Samuel Proctor name is deeply esteemed and Ms. Smith’s connection there is indication of her stature. Perhaps more importantly, she’s known on the streets as a voice for faith-based social change; she has been involved in organizing in her home-town of Columbus, Ohio, and on the national level. She is involved with numerous social justice organizations, including Dr. William Barber’s Poor People’s Campaign. These short readings were designed for those who are feeling beleaguered and battered down in their activism during these hard days. Kudos to Whitaker House (not known for these sorts of social action books) for taking up the writings of this important sister in the struggle. PRE-ORDER IT NOW.

Created to Flourish: How Employment-Based Solutions Help Eradicate Poverty Peter Greer & Phil Smith (Hope International) $19.99 What a handsome, joyous, wonderful book this it. It is not new, but wanted to mention it here because we are so glad to stock it, and you may not know of it. I hope you do know about the remarkable ministry directed by Lancaster-based Peter Greer called Hope International. They do micro-financing and employment-based work in developing countries and, as such, know so much about what actually works in helping create human flourishing all over the world. This wonderful book — made with full color photography on nice paper, making it an attractive artifact of their good work — was formerly out in an edition called The Poor Will Be Glad. This updates that excellent book adding new insights from their recent years of good work. There is a foreword by Jeff Rutt, founder of Hope International. There is more I could say about this book, but know it is handsomely designed, with lots of great stories, and in this lovely resource you’ll learn a lot about the Biblical call to wholistic development and economic possibilities.

Created to Flourish: How Employment-Based Solutions Help Eradicate Poverty Peter Greer & Phil Smith (Hope International) $19.99 What a handsome, joyous, wonderful book this it. It is not new, but wanted to mention it here because we are so glad to stock it, and you may not know of it. I hope you do know about the remarkable ministry directed by Lancaster-based Peter Greer called Hope International. They do micro-financing and employment-based work in developing countries and, as such, know so much about what actually works in helping create human flourishing all over the world. This wonderful book — made with full color photography on nice paper, making it an attractive artifact of their good work — was formerly out in an edition called The Poor Will Be Glad. This updates that excellent book adding new insights from their recent years of good work. There is a foreword by Jeff Rutt, founder of Hope International. There is more I could say about this book, but know it is handsomely designed, with lots of great stories, and in this lovely resource you’ll learn a lot about the Biblical call to wholistic development and economic possibilities.

Jesus’ Economy: A Biblical View of Poverty, The Currency of Love and a Pattern for Lasting Change John D. Barry (Whitaker House) $15.99 I was amazed that folks I respected from a variety of theological views and who tend to tilt left or right, so to speak (favoring more governmental adjustments to reform the economy or those who trust the free market as the best way to bring people out of poverty) all agreeing that this author is a gem, that this book is a great little guide. John Barry is one well-respected, behind the scenes leader.

Jesus’ Economy: A Biblical View of Poverty, The Currency of Love and a Pattern for Lasting Change John D. Barry (Whitaker House) $15.99 I was amazed that folks I respected from a variety of theological views and who tend to tilt left or right, so to speak (favoring more governmental adjustments to reform the economy or those who trust the free market as the best way to bring people out of poverty) all agreeing that this author is a gem, that this book is a great little guide. John Barry is one well-respected, behind the scenes leader.

Barry is a Biblical scholar and has worked in business, and is known as a missionary, I suppose. His bibliography is loaded with excellent resources on missiology and, better, his book is loaded with first hand accounts of folks from all over the developing world who lives – body and soul, communities and cultures – were transformed by a Kingdom vision of Christ’s Lordship in their lives. This is a great, easy-to-read manifesto about God’s love, about the way of Jesus, about His Kingdom coming all over the world and, especially, about the best ways to alleviate poverty and injustice. He is convinced that Jesus’ teachings are the guide to help us make better choices than can help us all help make the world a better place. Simple, direct, clear, and good introduction to a wholistic gospel and economic development strategies. Read something like SIlence Can Kill: Speaking Up to End Hunger and Make Our Economy Work for Everyone by Art Simon, I’d say, but this is a fabulous intro.

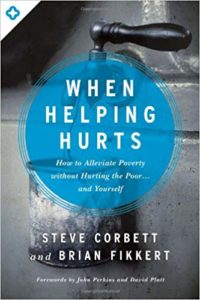

Becoming Whole: Why the Opposite of Poverty Isn’t the American Dream Brian Fikkert & Kelly Kapic (Moody Press) $15.99 Wow, what a book! I have alluded to this before, mentioned it at book groups, and shown it here in the shop. It deserves an even more detailed review that I am able to do at this time, but, trust me – it deserves your attention. An important project of The Chalmers Center (at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis) it is, in a way, a prequel to the bestselling and much discussed When Helping Hurts. Many have read that important volume (alongside the equally valuable Toxic Charity and Charity Detox by Robert Lupton) and somehow concluded that all foreign aid (or even local charitable mission) is suspect. This has become so common that Calvin College Press published a helpful little study called When Helping Heals by Tracy Kuperus & Roland Hoksbergen (Calvin College Press; $10.99.)

Becoming Whole: Why the Opposite of Poverty Isn’t the American Dream Brian Fikkert & Kelly Kapic (Moody Press) $15.99 Wow, what a book! I have alluded to this before, mentioned it at book groups, and shown it here in the shop. It deserves an even more detailed review that I am able to do at this time, but, trust me – it deserves your attention. An important project of The Chalmers Center (at Covenant Theological Seminary in St. Louis) it is, in a way, a prequel to the bestselling and much discussed When Helping Hurts. Many have read that important volume (alongside the equally valuable Toxic Charity and Charity Detox by Robert Lupton) and somehow concluded that all foreign aid (or even local charitable mission) is suspect. This has become so common that Calvin College Press published a helpful little study called When Helping Heals by Tracy Kuperus & Roland Hoksbergen (Calvin College Press; $10.99.)

Of course few would argue with the central thesis of When Helping Hurts. Too often big bureaucracies and government programs, or smaller, well-intentioned local charities, are patronizing, even toxic, and build dependency. Nobody wants poor folks to be dependent on somebody else’s charity. And, really, nobody wants to serve our needy neighbors in ways that are hurtful. But yet, we do.

Of course few would argue with the central thesis of When Helping Hurts. Too often big bureaucracies and government programs, or smaller, well-intentioned local charities, are patronizing, even toxic, and build dependency. Nobody wants poor folks to be dependent on somebody else’s charity. And, really, nobody wants to serve our needy neighbors in ways that are hurtful. But yet, we do.

Well, Fikkert and Kapic want to be sure we understand the philosophical assumptions and theological anthropology – a view of society and the person and the like – that informed their big-seller. If When Helping Hurts is a critique, what should we do, to do service well? We’ll get to that – there is a third volume in this trio of books – but, for now, this text, Becoming Whole is a full, nicely written, clear study of what human flourishing is. Obviously, merely helping poor people become rich isn’t the goal. Obviously, helping dysfunctional, unjust economies work more efficiently isn’t enough. Helping Mammon win isn’t what we want, is it? Becoming Whole, then, is a companion volume to When Helping Hurts. It can be read as a stand-alone or as a prequel.

This is one of the reasons I love Becoming Whole. It brings together a Biblical world and life view, a coherent public theology, a seriously Christian social analysis that both affirms jobs and markets and askews receiving simple handouts as normative ways for people to live, but doesn’t suffer under allusions of progress, as if more money is going to solve problems of a fragmented culture and lonely souls. Whether we are helping poor folks at home or abroad, whether we are trying to figure out a Christian view of economics or society, this book exposes the misconceptions and idols of Western culture (and, too often, the Western church.)

I think this book, therefore, is great for any of us, whether we are involved in poverty alleviation ministries or not. With sections like “The Shaping Power of Stories” you know it’s on to something good. And the middle section is so good! This section is called “When False Stories Make Helping Hurt” – warning against two main visions/stories. These two false visions are “you can become a consuming robot” or “who can be a harp-playing ghost forever.” Their Reformed worldview has long been strong in critiquing the errors of this sort of naturalistic consumerism (on one hand) and other-worldly pietism (on the other) but it doesn’t hurt that they’ve been reading N. T. Wright.

They even reference the cult-classic novel Flatland. And then, in “God’s Story of Change” offer a reconsideration of creation, a realization about the profundity of sin and the fall, and the “full embodied hope” of redemption as we await the dawning of the new creation. This is good, good stuff as we all try to live into that creation-fall-redemption-restoration story.

As the publisher promised in their description of Becoming Whole.

Through biblical insights, scientific research, and practical experience, they show you how the good news of the kingdom of God reshapes our lives and our poverty alleviation ministries, moving everybody toward wholeness.

A Field Guide to Becoming Whole: Principles for Poverty Alleviation Ministries Brian Fikkert & Kelly M. Kapic (Moody Press) $14.99 Okay, as I suggested above: a few years ago this team from the Chalmer’s Center put out what became a best seller, When Helping Hurts. They did a side-project called When Helping Hurts in Church Benevolence and a video curriculum on short-term mission trips. It’s a big deal, and good stuff.

A Field Guide to Becoming Whole: Principles for Poverty Alleviation Ministries Brian Fikkert & Kelly M. Kapic (Moody Press) $14.99 Okay, as I suggested above: a few years ago this team from the Chalmer’s Center put out what became a best seller, When Helping Hurts. They did a side-project called When Helping Hurts in Church Benevolence and a video curriculum on short-term mission trips. It’s a big deal, and good stuff.

Then, as I mentioned above, they did a prequel to all of this, concerned that the theological and worldviewish framework for their work would help people better understand their proposals about how to best serve those who are in poverty or hurting.-Becoming Whole: Why The Opposite of Poverty isn’t the American Dream is that volume, and it is wise and helpful instruction. Whether you’ve read When Helping Hurts or not, Become Whole is highly recommended.

And now, there is this, the potent little sequel. This little field guide is just that – a no-nonsense field guide to applying the big picture worldview stuff of Becoming Whole in a setting where the principles of When Helping Hurts are taken seriously Of course, there is no “one size fits all” solution, so they don’t call this a “how-to manual.” It really is an evocative field guide, unpacking “ministry design principles” developed over decades. It promises to offer valuable guidelines as you seek to live into God’s story in your particular context.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

20% OFF

ANY BOOK MENTIONED

+++

order here

this takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown PA 17313

read@heartsandmindsbooks.com

717-246-3333