Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology James K.A. Smith (Baker Academic) $22.95 — our 20% off sale price = $18.39

Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology James K.A. Smith (Baker Academic) $22.95 — our 20% off sale price = $18.39

We are glad to announce that the publisher has shipped to bookstores this much-anticipate third volume of the much-discussed “Cultural Liturgies” project by our friend, the beloved professor Jamie Smith. Smith holds the Byker Chair in Reformed Theology and Worldview at Calvin College in Grand Rapids; he had previously studied at the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto with long-distance mentors of ours such as Al Wolters and Brian Walsh and did his PhD in postmodern hermeneutics with Dr. Jack Caputo at Villanova. He’s remarkably down to Earth – he loves hockey and NASCAR and indie rock music — and is amazingly smart. He edits the most interesting quarterly we know, the lovely Comment, a journal of thoughtful but accessible public theology, offered in the spirit of Abraham Kuyper’s efforts to re-think and revitalize the social architecture of society. I’ve even written for Comment, but these days they draw on some of the world’s finest minds and significant practitioners of this sort of robust, wise, culturally-transformative faith.

If you want to order this third “Cultural Liturgies” installment – or the first two, Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview & Cultural Formation ($22.99) and Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Words ($22.99) – and don’t want to read my long essay below, click HERE to jump to our secure website order form. Just type in what you want and your credit card info as instructed. We’ll send your order our right away.

If you have purchased from us the previous two, or are doing so now, let us know if you would like us to include with your purchase of Awaiting the King a new very handsome heavy-stock paper slipcase to show off all three books together. You can buy all three shrink wrapped in the slipcase, for that matter, but if you already have the previous two, we’ll send along a slipcase for free. Just let us know if you want it.

To order the book at our website, you can safely enter credit card digits as instructed or simply tell us if you want us to enclose an invoice with the shipment so you can pay by check later. All three “Cultural Liturgy” books are 20% off (making them $18.39 each) and we’d be happy to serve you promptly.

THE SHORTER REVIEW

Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology is an intellectually rigorous book, bringing us a sustained conversation on Smith’s own political thinking – a remarkable blend of influences from Augustine, Calvin, Kuyper, and Bavinck, engaging with Oliver O’Donovan, Stanley Hauerwas, and Peter Leithart, inspired always by wise evangelical thinkers such as Robert Webber and Richard Mouw.

Awaiting allows JKA to help us enter the conversation about any number of themes and controversies among those who think about social ethics and public theology and Christians speaking out in public. He says, for instance, why he thinks “natural law” is a less than helpful approach to Christian scholarship, tells what was up with the “radical orthodoxy” movement, and shows why we always need some prophetic, critical distance from our too easily accommodated tendencies (whether we are conservative evangelicals tilting right or mainline denominational leaders tilting left or Kuyperian transformationalists who, in the name of making a difference, are too readily informed by their own biases and social settings, perhaps too much at ease in Babylon.) To show how important and urgent all this is, he weighs in matters of racial justice and how we in our churches construe racial identity. In not even 300 pages he covers a whole lot of ground.

One doesn’t need the punchy, eloquent quotes from British theologian and ethicist Oliver O’Donovan that open the book to know that to proclaim the gospel necessarily is an act laden with political implications. Indeed, as you’ll see, even that way of putting it is inadequate: it’s not that the gospel has political implications, but it is political in its essence. Our best thinkers from the earliest Christian martyrs through Bonhoeffer and Barman, on to Dorothy Day, Lesslie Newbigin, Rowan Williams, and both Jim Wallis and Chuck Colson, all agree that to say Jesus is Lord implies that “Caesar” is not. Announcing the Kingdom of God is a political act.

But how do we best frame our thinking about our public, civic, and political lives? Neither “quietism or activism” Smith says, in a line about the so-called Benedict Option. Although informed by the Kuyper slogan about “every square inch” of the entire creation and culture being claimed by Christ, Smith (not surprisingly, given his emphasis in Desiring the Kingdom on worshiping well with the local congregation) tells of reading Resident Aliens by United Methodist church guys Hauerwas and Willimon and realizing that, as he puts it frankly, “I lacked a functional ecclesiology.”

There is a connection that is fairly widely recognized, but not often enough explored between our congregational vitality and church life and our activities in the marketplaces, public squares, and civic/political spaces

As followers of Jesus who are part of His first family, the global Body of Christ, shaped by our own “cultural center of gravity” found in the church, we must learn to “actively wait” in what he calls “the meantime of the saeculum.”

You see, there are two things going on here: waiting for Christ’s return, even in our seemingly secular, public, informs our posture as citizens and neighbors, and, we learn to do that in church, shaped as we are not only by worship, but by the ways of being together as a congregation. We learn our best practices of public social ethics within the parish.

Well.

I will explain more later, but I am convinced this is the Book of the Year.

I will explain more later, but I am convinced this is the Book of the Year.

We believe, quite frankly, that many Hearts & Minds customers should buy it from us.

I seriously believe that this book is so important that I implore you to consider it. I am confidant that this trilogy of books are among the most important books written in the 35 years we’ve been at this bookselling business. One does not have to read the first two to appreciate Awaiting, although, obviously, this is the third in a series.

Especially if you’ve read his nicely summarizing one volume version, You Are What You Love, you are ready to dig deep into Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology.

Especially if you’ve read his nicely summarizing one volume version, You Are What You Love, you are ready to dig deep into Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology.

It is a great joy to get to commend such academically rich and yet engaging resources for our common life “in but not of” the world. In this era of Trumpism and (as Smith explores) rising white nationalism, little more could be as pressing as to get beyond the too common escapism of conventional evangelical pietism or mainline denominational accommodation to mainstream middle-class culture and politics in order to forge a responsible, brave (and dare we say, healing) third way? More clearly than nearly any author we know, Smith dives deep into the complex waters of what it really means to be (as we like to say) neither left nor right, rejecting the idolatrous assumptions of conservatism and progressivism, seeking a better way. No matter your own political inclinations, Smith will surprise, challenge, and hopefully delight you with commendable, fresh insights.

I will say this again, in my longer rumination below, but for the record I want to say that the footnotes (and the helpful comments within them) are extraordinary; Smith is an amazingly widely read scholar and an excellent teacher. Just reading the footnotes themselves is like joining an advanced seminar in political theology, learning about Rawls and Stout, Hauerwas and Van Prinsterer, Dooyeweerd and Bauckham. From civic thinkers John Inazu and Yuval Levin discussed alongside the

I will say this again, in my longer rumination below, but for the record I want to say that the footnotes (and the helpful comments within them) are extraordinary; Smith is an amazingly widely read scholar and an excellent teacher. Just reading the footnotes themselves is like joining an advanced seminar in political theology, learning about Rawls and Stout, Hauerwas and Van Prinsterer, Dooyeweerd and Bauckham. From civic thinkers John Inazu and Yuval Levin discussed alongside the  philosophers Alvin Plantinga and Charles Taylor, for instance, you will learn much and will be challenged to ponder much. If you want to be brought up to speed – at a graduate school level – on the most important thinkers writing in this field these days, Awaiting the King will assist you. In a way, for those of us too busy or limited to grapple with all the array of scholars Smith is paid to think about, this book is a fabulous summary that will allow you to follow the biggest conversations happening in confabs and journals and meetings and debates all over the country. Awaiting is admittedly serious writing about serious thinking, but these are, after all, serious times.

philosophers Alvin Plantinga and Charles Taylor, for instance, you will learn much and will be challenged to ponder much. If you want to be brought up to speed – at a graduate school level – on the most important thinkers writing in this field these days, Awaiting the King will assist you. In a way, for those of us too busy or limited to grapple with all the array of scholars Smith is paid to think about, this book is a fabulous summary that will allow you to follow the biggest conversations happening in confabs and journals and meetings and debates all over the country. Awaiting is admittedly serious writing about serious thinking, but these are, after all, serious times.

And yet, Dr. Smith is ever the good teacher. As in Desiring the Kingdom and Imagining the Kingdom, he offers in each chapter fun stories, great examples, even sidebars full of case studies. Yes, he cites a lot of scholars but he also gives fine illustrations from his own life, or from films or stories, to flesh out his theorizing. Few academic books are as lively; few scholars are as gifted at teaching and preaching. If you take it slowly, you can do this.

Don’t forget that Smith has wonderfully, significantly, summarized the gist of these three books in his best-selling You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habits (Baker; regularly $19.99; on sale now for $15.99.) I have touted this one, too, as practically a book of the decade, largely because we are fully aware that this sort of more accessible volume is needed to give many readers a powerful overview of Smith’s work in this “cultural liturgies” project. If you’ve appreciated that great book, it may be time to dig deeper and explore where it all goes in this third installment of the big set.

Don’t forget that Smith has wonderfully, significantly, summarized the gist of these three books in his best-selling You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habits (Baker; regularly $19.99; on sale now for $15.99.) I have touted this one, too, as practically a book of the decade, largely because we are fully aware that this sort of more accessible volume is needed to give many readers a powerful overview of Smith’s work in this “cultural liturgies” project. If you’ve appreciated that great book, it may be time to dig deeper and explore where it all goes in this third installment of the big set.

If you like the sound of this, but find it all a bit daunting, at least be sure to pick up You Are What You Love as it truly is a provocative valuable read.

I do not want to overstate this, but Awaiting the King even surprised Smith himself a bit as it unfolded in the writing process. Smith wrote the singular You Are What You Love after having written the first two volumes of the bigger “Cultural Liturgies” set. He had done Imagining the Kingdom and Desiring the Kingdom and speculated on what he’d be writing in the third, putting it all into You Are What You Love, so that last portion of You Are What You Love gives a glimpse of what he thought it would be like to write a third volume about embodying the Kingdom.

I do not want to overstate this, but Awaiting the King even surprised Smith himself a bit as it unfolded in the writing process. Smith wrote the singular You Are What You Love after having written the first two volumes of the bigger “Cultural Liturgies” set. He had done Imagining the Kingdom and Desiring the Kingdom and speculated on what he’d be writing in the third, putting it all into You Are What You Love, so that last portion of You Are What You Love gives a glimpse of what he thought it would be like to write a third volume about embodying the Kingdom.

Alas, as he says in the front of Awaiting, it seems like he changed his approach just a bit, that his trajectory from the first two pointed him, finally to all of this about distinctive social ethics. Some of his approach to “reforming public theology,” perhaps, came from discussions and feedback from the many speaking engagements all over the world he’s done on this stuff. Perhaps he shifted his interest from Anabaptist John Howard Yoder to Anglican Oliver O’Donovan, from Hauerwas back to Augustine. Which is only to say that if you’ve read the final few chapters of You Are What You Love pretty carefully you might be surprised at the tone and convictions shaping Awaiting.

Awaiting the King makes a complex and nuanced case, but don’t be alarmed, fearing that it is overly arcane. In many ways it is about how to have solidarity with our neighbors, and with others with whom we share space in our common lives. It is about how to live with our deepest differences. It is about what we really want for the world, hopefully tethered tightly to what we expect God wills as Christ’s Kingdom comes. In the preface Smith says he hopes this book offers insights about the “how” of being in the world as Kingdom people. He calls it – after a reminder of how unhelpful culture warring has been – “an exercise of psture correction: part diagnosis and part prescription.”

It isn’t surprising to hear his rousing hope that the book would be,

…a way of reframing the liturgical heritage of the church as a resource for the Spirit to shape a peculiar people for the common good.

Enough said, for now, I suppose. If you want to order this, please do. It is worth having in your library, even if you don’t have time to study it now. As I’ve said, we are sincerely eager to send these out and you can order easily at our secure website order form page by scrolling to the bottom of this column.

All books mentioned are 20% off. Let us know if you need one of those slipcases for all three, if you’ve bought them from us previously. We can send one of those along while supplies last.

****

If you’d like to look over my shoulder at a bit more of my reflections about the book, started when I was at the National Gathering of the Christian Legal Society, read on.

SITTING SLACK-JAWED AT CLS

I’m sitting here in the conference meeting room with my spiral bound advanced copy of Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology, the third volume in the highly regarded and much-discussed “Cultural Liturgies” trilogy by Calvin College philosopher and Comment magazine helmsman, James K.A. Smith. My lap top literally on my lap, I hardly know where to begin, even though I’ve been reading and thinking and jotting notes about this for weeks.

I’m sitting here in the conference meeting room with my spiral bound advanced copy of Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology, the third volume in the highly regarded and much-discussed “Cultural Liturgies” trilogy by Calvin College philosopher and Comment magazine helmsman, James K.A. Smith. My lap top literally on my lap, I hardly know where to begin, even though I’ve been reading and thinking and jotting notes about this for weeks.

At the moment we are out in California. Beth and I and our Hearts & Minds staff have curated and shipped a large book display to the annual Christian Legal Society National Conference. It seemed like a good place to finalize my thoughts about the most important book I’ve read all year, a book that I found both challenging and stimulating. It is a book I very much want our BookNotes readers and customers to know about; I want to be on record as a long-standing fan and a cheerleader for Smith and certainly this trio of “Cultural Liturgy” books. This brand new third one is simply extraordinary; it is erudite and prophetic, beautiful and difficult. It brings together some authors that have influenced my own development from rather unusual corners of the Kingdom, and it makes me glad to know I am not alone in wanting to value Kuyper and Hauerwas; Nicholas Wolterstorff and Charles Marsh, David Foster Wallace and Marilyn Robinson.

But here I am, hardly able to conceive how to explain the value of this rich, learned, passionate call to think well about public life. What do we do with his wise insights about the social ecology of institutions shaping our character? Is he right about “calculated ambivalence”? Why do I get choked up when I re-read his section “In Praise of the Quixotic”? How can I thank this author for saying in print what I have preached from stages and classrooms and pulpits for decades, that “our most revolutionary political act is to hope” even though I learned it from authors Jamie doesn’t cite, such as Thomas Merton, Jacques Ellul, Jim Wallis and Daniel Berrigan? (And, of course, I am reminded of Reclaiming Hope the memoir written by my friend Michael Ware about his challenging years serving the Obama White House, and his wonderful last chapter on hopefulness. I wonder what he thinks about this dense but rewarding book?)

LAW SCHOOL DEAN ERIC ENLOW ON PRAISING GOD FOR LAW

I’m sitting with typing fingers limp not just because I feel inadequate as a reviewer of such a substantive, important book, but because I am slack-jawed from just hearing a lecture by one of the very smartest and deeply-read guys I know – Eric Enlow, the Dean of a Christian law school in Handong, Korea. Dean Enlow, who did his undergraduate work at Yale, lectured beautifully at an academic symposium at the CLS conference (and will preach on Sunday) on how to find joy in the study and practice of law; the ancients have written widely on this, that we have a duty to praise the good, and, more wondrously, to praise God for the good God has given us. Even though this judge or that legislative body or some itineration of supreme courts gets it wrong sometimes, they sometimes get it right and in all such things – an ordered creation, designed for human flourishing – we are to give God praise.

Enlow cited (as if well-educated Christians knew these ancients) early church Fathers, public intellectuals speaking during the fall of the Roman Empire (who, as we know from Augustine, pondered much about history and law and justice and the Christians obligations in the “city of man.”) He told of medieval Spanish jurists and Reformation-era legal scholars – Melancthon wrote about civil law, did you know that? Calvin was a legal scholar, as you probably know, and his famous Institutes were dedicated to the French King — and so many more. We had on the book table copies of the marvelous, if expensive, history of British jurists such as John Selden and Sir John Fortescue who were Christians with dozens of chapters by reputable world-class scholars, edited by the extraordinary John Witte, Jr and published by Cambridge University Press (which has a whole series of academic works on the interface of Christian faith and legal theory.) Showing that the historic, global church calls us to praise God for law, and to therefore be joyful in our struggle to bear witness to God’s redeeming work as history unfolds – think of Ephesians 1:10 or Colossians 1: 15-20 – even in matters of civil law and public justice and principled pluralism and controversies of religious liberty and so on, was exceptionally helpful for me to hear. How important to be reminded that we are not the first to formulate ways to think Christianly about (in this case) law and jurisprudence and, more generally, reminded of a faithful posture towards God’s gifts of a ordered creation and the possibilities of a just public culture.

To get to be a part of a group of Christian attorneys and students and judges as they were encouraged to praise God in and through and for the law we very, very moving for me.

You can access a series of a dozen lectures by Dean Eric Enlow on Youtube from a law class he teaches, and here is one that covers some of the stuff about the praise of God in law. I know I’m going to view some of the lectures as his speaking at CLS was deeply meaningful to me, even if I don’t always understand it all and even if I have a hunch I don’t always agree with his astute formulations. (In fact, CLS staffer and dear friend Michael Schutt has an occasional podcast called The Cross and the Gavel and right after Eric’s lecture, Mike and I recorded a further discussion with Eric, sitting in the big bookroom at CLS where I probed a bit, the best I could, to get Eric to further explain his views about praising God for law, and honoring the good in civic society. Visit the “Cross and the Gavel” audio to see when Schutt gets that good conversation posted.)

You can access a series of a dozen lectures by Dean Eric Enlow on Youtube from a law class he teaches, and here is one that covers some of the stuff about the praise of God in law. I know I’m going to view some of the lectures as his speaking at CLS was deeply meaningful to me, even if I don’t always understand it all and even if I have a hunch I don’t always agree with his astute formulations. (In fact, CLS staffer and dear friend Michael Schutt has an occasional podcast called The Cross and the Gavel and right after Eric’s lecture, Mike and I recorded a further discussion with Eric, sitting in the big bookroom at CLS where I probed a bit, the best I could, to get Eric to further explain his views about praising God for law, and honoring the good in civic society. Visit the “Cross and the Gavel” audio to see when Schutt gets that good conversation posted.)

And, oh, how I wish Jamie Smith could be here, offering dialogue with Eric and the others of varying denominations and perspectives; perhaps you know such venues of thoughtful public leaders (maybe your own CLS chapter if you folks are reading along here, or college political science professors or local elected officials) should form a study group on Awaiting the Kingdom. Smith’s insights and clear writing would be a fruitful asset for any such professional gathering of those who, one would think, would be very interested in his profound argument about public faithfulness.

Enlow’s rich, historic call to Christian lawyers and judges and law students and teachers to be thoughtful about our consideration of first things, aware of the very ordered structure of God’s good world which provides the possibilities of laws and institutions for human flourishing, leaning in to the cosmic scope of Christ’s Kingship, and the acknowledging the beauty of our knowledge about important things in Christ – what riches have been revealed to us! – was only one part of the marvelous CLS conference. I hope you don’t mind me telling you about it.

JERRY ROOT ON JOY IN CS LEWIS

SAMUEL RODRIGUEZ ON BEING THE LAMB’S LIGHT

JOHN STONESTREET ON CULTURAL CHANGE

We heard keynote addresses of a similar nature by the thoughtful and gracious C.S. Lewis scholar and author Jerry Root (who happily bought the first book of the CLS event, a novel about lawyering written by Inkling Owen Barfield, who Professor Root had once met.) We hosted a book signing for him and several other authors in the house, including the passionate Latino preacher Samuel Rodriguez (“be light” he admonished!) and Breakpoint radio host John Stonestreet, who powerfully told about the anti-Hitler student activism and martyrdom of college age brother and sister Hans and Sophie Scholl, quoting Steve Garber’s Fabric of Faithfulness: Connecting Belief and Behavior. Each of their lectures will soon be shown at the CLS website and they are well worth viewing. Naturally, we hope that if you are inspired to buy any of the books they’ve written (or that they mention in their passionate presentations) that you get ‘em from us. It’s a joy and blessing for us to hear such renowned, wise speakers but the point, of course, is to make a living selling books. We’re glad you care and we appreciate your support.

ALL CITIZENS NEED SMITH BUT ESPECIALLY THOSE SERVING PUBLIC LIFE

Which brings me back to how stymied I was sitting there with the new James KA Smith “Cultural Liturgies” volume 3 book in my lap after Enlow’s lecture about praising God for the good, for honoring law and public order, for desiring justice and finding joy in awaiting the final restoration of all things promised in the Bible, the creeds, and the best Christian teaching of two millennium. I’ve been reading Smith’s vibrant, thick, call to seriously faithful thinking about public theology, to consider a Christian political option, and realize he has insights that all of us badly need (even those scholars and leaders who specialize in this sort of thing. How often here at the CLS national gathering have I found myself thinking “if only they had read Smith. If only we had that Awaiting the King book that is releasing any day now.” Being surrounded by scholars and the sorts of lawyers who have argued before the Circuit Courts, before the Justices of state’s Supreme Courts, who have published law review articles, I want to shout that this book will inspire and help and perhaps serve as a corrective to your good work. Being among some who call themselves “culture warriors” made me want to offer this book as a “posture corrective.” I had my advanced copy of the manuscript and was waving it around everywhere I went.

BEING PAINFULLY HONEST WITH YOU: I AM EXCITED AND FEARFUL

While being reminded so eloquently about all this good stuff about the value of public life and the God-ordained call to social/political theology by CLS scholars and activists, being here in communion with other speakers and day-to-day attorneys (including some who are giving their very livelihoods to the poor by serving pro bono at faith-based legal aid clinics or standing with immigrants who are too often victimized by heartless government bureaucracies) I am both excited and fearful.

Here’s why.

Maybe you entertain similar anxieties and maybe Awaiting the King will help you.

At least sharing with you some ruminations about my excitement and my anxiety might help you see why I’m going to such lengths to ponder this book and to persuade you to order it from us. Awaiting the King is important, and, well…

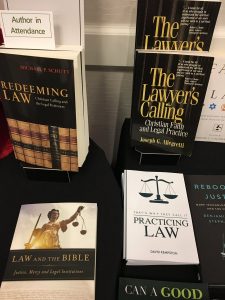

I am excited in the moment as we are selling books here at CLS of all sorts to good people who care. The book-selling opportunity at this conference is a blessing to us and folks here  tell us they find it helpful to actually browse in an intentionally selected display of relevant books about being a Christian lawyer. We’ve got introductory ones like John Mauck’s recent Jesus in the Courtroom: How Believers Can Engage the Legal System for the Good of His World (Moody; $13.99) or Michael Schutt’s serious classic Redeeming Law: Christian Calling and the Legal Profession (IVP; $22.00), which, by the way, is now available in Chinese. We gave books of a more general sort for spiritual formation and vocational discipleship from Richard Foster to

tell us they find it helpful to actually browse in an intentionally selected display of relevant books about being a Christian lawyer. We’ve got introductory ones like John Mauck’s recent Jesus in the Courtroom: How Believers Can Engage the Legal System for the Good of His World (Moody; $13.99) or Michael Schutt’s serious classic Redeeming Law: Christian Calling and the Legal Profession (IVP; $22.00), which, by the way, is now available in Chinese. We gave books of a more general sort for spiritual formation and vocational discipleship from Richard Foster to  Tim Keller, from Amy Sherman’s Kingdom Callings to Steve Garber’s Visions of Vocation to wonderfully important reads by authors that were with us such as Angry Like Jesus by Sarah Sumner (Fortress Press) and The Peacemaker by Ken Sande (Baker) and the provocative monograph From Telos to Technos: Implications for a Christian Public Life and Ethic by Jeffrey J. Ventrella of the Alliance Defense Fund (which, at $7.99, is really worth reading.)

Tim Keller, from Amy Sherman’s Kingdom Callings to Steve Garber’s Visions of Vocation to wonderfully important reads by authors that were with us such as Angry Like Jesus by Sarah Sumner (Fortress Press) and The Peacemaker by Ken Sande (Baker) and the provocative monograph From Telos to Technos: Implications for a Christian Public Life and Ethic by Jeffrey J. Ventrella of the Alliance Defense Fund (which, at $7.99, is really worth reading.)

One book that sold well at CLS should be of interest to many Hearts & Minds friends. It is brand new, written by former law school Dean Jeffrey A. Brauch, called Flawed Perfection: What It Means to Be Human and Why It Matters for Culture, Politics, and Law (Lexham Press; $15.99.)

One book that sold well at CLS should be of interest to many Hearts & Minds friends. It is brand new, written by former law school Dean Jeffrey A. Brauch, called Flawed Perfection: What It Means to Be Human and Why It Matters for Culture, Politics, and Law (Lexham Press; $15.99.)

Brauch is certainly right to say that our view of who we are – the Bible says we are gloriously made in God’s image and wretchedly alienated and distorted – will decisively effect how we think about culture and social issues. After some excellent teaching on a Christian anthropology (that is, a view of the person) he offers inspiring ideas about topics such as global injustice, human trafficking, bio-ethics, religious liberty, and more. It’s good stuff, and a fine example of Smith’s big vision: we must imagine a good creation and a Kingdom perspective, informed by our deepest understandings of the story we are a part of. Who we are matters, where we are heading matters, and our opinions about ethical quandaries and public justice must be shaped (if we are to be faithful Christians) by our arche and telos.

It is invigorating to offer thoughtful books to help people in their faith and life, and we were thrilled to sell almost all of the copies of Smith’s one-volume You Are What You Love which, I trust you know by now, is a summary of Imagining the Kingdom and Desiring the Kingdom and what would become Awaiting the King. It gives me hope that there is a big market for thoughtful books, for resources about vibrant and faithful discipleship in the context of the secularizing, complex, hurting modern world.

It is invigorating to offer thoughtful books to help people in their faith and life, and we were thrilled to sell almost all of the copies of Smith’s one-volume You Are What You Love which, I trust you know by now, is a summary of Imagining the Kingdom and Desiring the Kingdom and what would become Awaiting the King. It gives me hope that there is a big market for thoughtful books, for resources about vibrant and faithful discipleship in the context of the secularizing, complex, hurting modern world.

So, yes, as I said, I’m excited, glad, grateful, even upbeat. Smith’s work is indicative of a very good trend in religious discourse and his books are an example of the very best of Christian publishing these days.

But I am anxious, too.

I sense here among my good friends at the conference that we in the church still are a bit too loyal to our largely secular ideologies of the left and right. Many of these fine Christian legal scholars articulate a classic Christian conservativism that I find a bit disconcerting, even if their vision is more Bill Buckley or Russell Moore than anything Falwell or Trump might articulate. When I heard a young female law student from Liberty gush that she loooved Donald Trump I almost cried. What is wrong with people to be so enamored with such a vile person?

A few others, somewhat in reaction to the blind spots of conservative, natural law types that seem fixated on religious freedom and the erosion of a conventional view of marriage, are animated by a passion for those oppressed by systemic racism and economic injustice. Rather than talking mostly about liberty they talk about justice. Interestingly, both sides cite Isaiah 1:10 and Micah 6:8 and Matthew 25. As you might guess, I’m eager to bring both wings together. And I am convinced that James KA Smith’s work can help.

RADIX

Smith’s project is vital and exceptionally thoughtful but he isn’t the only one inviting us to this distinctively, radical Christian view – we get the word radical from the Latin radix, by the way,  which means “root” so a “radical” view must be foundational, starting at the level of assumptions and presuppositions, considering the deepest roots of things, perhaps even the nature of the soil those roots are rooted in. We dare not be firstly loyal to the soil of conservative principles or progressive values (let alone the status quo, which may be the biggest danger of all) but Biblical teaching, putting ourselves deeply into the redemptive narrative, forming a Christian imagination out of which can emerge more finely tuned Christian consideration of visions and policies. One serious book about this very matter is by David Koyzis, entitled Political Visions and Illusions: A Survey & Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies (IVP; $27.00) which I often suggest but rarely sell. Hmmm.

which means “root” so a “radical” view must be foundational, starting at the level of assumptions and presuppositions, considering the deepest roots of things, perhaps even the nature of the soil those roots are rooted in. We dare not be firstly loyal to the soil of conservative principles or progressive values (let alone the status quo, which may be the biggest danger of all) but Biblical teaching, putting ourselves deeply into the redemptive narrative, forming a Christian imagination out of which can emerge more finely tuned Christian consideration of visions and policies. One serious book about this very matter is by David Koyzis, entitled Political Visions and Illusions: A Survey & Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies (IVP; $27.00) which I often suggest but rarely sell. Hmmm.

And so, I’m worried. We need Smith’s nuanced conversation about being in but not of the culture, about how to best work for the transformation of the ecology of public institutions, civic structures, political organizations and such. His sort of approach (which I believe reveals a radical, deep wisdom) isn’t on display much these days in what we sometimes call the public square.

He says, by the way, quite interestingly, that the phrase “the public square” is unhelpful. It may be an off-handed aside, but it makes a significant point about political ecologies and Smith’s multi-faceted, Kuyperian worldview.

He reminds us,

The political is not a square with discernible gates. While we often speak of the public “square,” the metaphor is antiquated and unhelpful. There’s no square there. And it certainly isn’t the case that “the political” is restricted to our capitols, legislatures, and polling booths. The political is not synonymous with, or reducible to, the realm of “government,” even if there is significant overlap.

He means more than this – recognizing the realties of our differentiated, multi-sphered social architecture, and the importance of mediating structures and civil society – but it brings to mind Steve Garber’s often used phrase that “culture is upstream from politics.”

HOPE

Smith ends his magisterial study of political theology with a reflection on hope, reminding us that novelist Marilynne Robinson succinctly observes that “Fear is not a Christian habit of mind.”

Smith continues,

To be a Christian is to be a person who engages in politics but does so without fear. Fear drives us to panic, and no one makes good decisions when they’re panicked. We overestimate some threats and ignore others. We can’t see clearly, and we’re prone to being manipulated by those who would foment our panic. But we ought not be a panicked people. Our King has told us over and over again, “Be not afraid.” You have already heard good news that brings great joy. The King is alive and seated on his throne, and he reigns. And no only that, he is interceding for us at the right hand of his faith. “Be not afraid.”

So, okay, we are not to fear. We are not to be panicky. This is good insight for both those who tend to tilt right and those who lilt left. We should be people of consistent principle and work out the implications of a Biblical worldview no matter what strange bedfellows it gets us. As the dramatic Latino preacher Samuel Rodriguez – author of Be Light and The Lamb’s Agenda – reminded us in his powerful CLS message, we aren’t that interested in donkeys or elephants, since our Lord is the Lamb.

WAITING ON THE RAMPARTS

But how do we move forward, active, joyful, responsible, not “building” God’s Kingdom (heaven forbid) but anticipating as good neighbors and citizens the renewal that we  anticipate? How do we wait in true hopefulness? The conclusion of Smith’s Awaiting the King ends exactly with this, drawing nicely on the wonderful book by Bethany Hanke Hoang & Kristen Deede Johnston, The Justice Calling: Where Passion Meets Perseverance (Brazos Press; $18.99.) Drawing on their remarkable insight, gleaned from years on the front lines fighting sexual abuse and human trafficking, and in the classroom nurturing a rising generation, Smith tells us that our Kingdom waiting, our posture and approach, is “not the timid waiting of quietism or the resigned waiting of indifference.” In The Justice Calling, Smith reports, Hoang & Johnson “look back to Habakkuk as an exemplar.” Smith tells us about their reminders:

anticipate? How do we wait in true hopefulness? The conclusion of Smith’s Awaiting the King ends exactly with this, drawing nicely on the wonderful book by Bethany Hanke Hoang & Kristen Deede Johnston, The Justice Calling: Where Passion Meets Perseverance (Brazos Press; $18.99.) Drawing on their remarkable insight, gleaned from years on the front lines fighting sexual abuse and human trafficking, and in the classroom nurturing a rising generation, Smith tells us that our Kingdom waiting, our posture and approach, is “not the timid waiting of quietism or the resigned waiting of indifference.” In The Justice Calling, Smith reports, Hoang & Johnson “look back to Habakkuk as an exemplar.” Smith tells us about their reminders:

Lamenting injustice, confronting God, Habakkuk stations himself on a rampart as he awaits God’s response to his complaint (Hab. 2:1.) “What could it mean for us to ‘station’ ourselves?” they ask. “What could a rampart represent in our own lives, and what would be the point of getting on top of it? What is the role of waiting when everything around us begs for action? Can waiting itself be an act?”

Oh, how I wish I could have had Awaiting the Kingdom: Reforming Public Theology in time to sell to these many Christian attorneys, legal scholars, judges, law students and their professors at the CLS gathering. Such folks need Smith’s systematic, serious explorations of what it means to have an imaginative Christian world-and-life vision, how being formed into the best Kingdom desires will shape our hopes for society, what public theology is, how worship can inform principled politics, and what it really looks like to be non-partisan Kingdom citizens, resident aliens in a broken world in need of renewal and hope. And, oh, how I fear – even though we’re not supposed to — in these times when watching the daily news tempts me regularly to despair that not enough Christians will care enough to do this kind of heavy homework to learn what the best practices for social renewal might be.

WHAT A MESS THESE DAYS

We are in a mess, with Christians of all sorts easily accommodated to the left or right. Or we are captive to our default position of smugly condemning all sides with self-righteous distance, passionate but practically disengaged (except for the social media rants of the day or signed Statements about this or that.) Slowly reading a thoughtful book on these very matters could be just the thing we need to jolt us out of our captivity or cynicism.

(If you are a recent subscriber to BookNotes, I suppose you should know that I’ve written about this before. Read my column lamenting the lack of the Christian mind in political thinking, here.)

I do know that some of us want to enter the fray but are unsure how to shift the conversation and political postures to more healthy places. We aren’t about grandstanding or hopping on bandwagons but we know we are sent, by God, into the world he loves and that should be working for the health and shalom of our land. But we feel almost helpless.

Do you know what I mean?

CH CH CH CHANGES

You see, I think we are in the most dangerous time of my lifetime. I came of age in the horrifying years of the late 60s and early 70s and played a small part in some of those uprisings and ch-ch-ch-changes. Most of us recall President Kennedy being shot, and then King and Bobby. We remember the pictures of the My Lai. massacre. I acted against the Viet  Nam war and have been locked up for protesting nuclear weapons and arrested for protesting abortion. I’ve stood arm in arm with Holocaust survivors speaking out against anti-Semitism and aged two decades in half as many years as a pro-immigration activist, standing with imprisoned Chinese asylum seekers here in York, PA. I’ve preached in front of the Capitol and I’ve had rifles aimed at me,

Nam war and have been locked up for protesting nuclear weapons and arrested for protesting abortion. I’ve stood arm in arm with Holocaust survivors speaking out against anti-Semitism and aged two decades in half as many years as a pro-immigration activist, standing with imprisoned Chinese asylum seekers here in York, PA. I’ve preached in front of the Capitol and I’ve had rifles aimed at me,  been stomped on by police horses, volunteered at soup kitchens, served in a Crisis Care Center and so on. I’ve tried to be active in mostly small ways about public life and the common good but find hope hard to come by. Times have always been perilous, more in the two-thirds world than here. I get that, too.

been stomped on by police horses, volunteered at soup kitchens, served in a Crisis Care Center and so on. I’ve tried to be active in mostly small ways about public life and the common good but find hope hard to come by. Times have always been perilous, more in the two-thirds world than here. I get that, too.

In all of this, though, importantly, I’ve taught about Christian philosophy, trying to encourage reading deeply about the joys of God’s good world and invited folks to deepen their own sense of God’s call upon their lives, serving well in whatever career or vocation they find themselves in. From the arts to the sciences, from family life to work and play, we celebrate that all of life is God’s and all of life is being redeemed. But few church folk  have thought this through and I fear we are not up to the challenge of the rising racism and the reign of crass, stupid stuff from the nation’s capital. I read and re-read Garber’s beautiful Visions of Vocation book about enduring faith amidst deep sorrow for our hurting world and try to take heart. I sense that a lifetime of speaking and writing and teaching and bookselling is nearly for naught as fellow citizens and many sincere church folks are falling like flies into the far right or the far left or, as Garber warns, devolving into cynicism or jaded apathy. I am glad that Christian hope is a different sort of thing than mere optimism, because I am not optimistic about these days in which we live.

have thought this through and I fear we are not up to the challenge of the rising racism and the reign of crass, stupid stuff from the nation’s capital. I read and re-read Garber’s beautiful Visions of Vocation book about enduring faith amidst deep sorrow for our hurting world and try to take heart. I sense that a lifetime of speaking and writing and teaching and bookselling is nearly for naught as fellow citizens and many sincere church folks are falling like flies into the far right or the far left or, as Garber warns, devolving into cynicism or jaded apathy. I am glad that Christian hope is a different sort of thing than mere optimism, because I am not optimistic about these days in which we live.

And too few of us – myself included (and I realize I get my books cheap and easily and have a job that allows me to study) – seem to have the capacity to build time into our schedule to read, reflect, ponder, and learn. We don’t seem to want to be “radical” (in that sense of very fundamentally, foundationally, deeply Christian.) Or maybe we don’t read and study much because we think we can just intuit a faithful and just and healthy sort of citizenship. Or maybe we’re just consumed with day to day tasks; I get that, too.

Yet, I fear that the gems of insight that are so timely and so valuable and so needed in books like Awaiting the King will be missed by those who most need them. I am afraid too few will take up the challenge to work on and think critically about a sophisticated book like this.

THAT TRICKY SUB-TITLE: REFORMING THE PUBLIC AND REFORMING OUR THEOLOGY

Maybe it would help to catch the word play of the double entendre in the subtitle. We need a reforming sort of public theology – one that works hard to change things, to bring Godly reform. But we need to be about reforming our public theology itself, as it has not served us well. Saying, as most do, that we shouldn’t “mix church and state,” while true enough, simply isn’t enough. We must revisit our theology and see what cues and hints and stories are implicit (or sometimes even explicit) in our theological truths and see how they might equip us to be more faithful in our public vocations.

Maybe it would help to catch the word play of the double entendre in the subtitle. We need a reforming sort of public theology – one that works hard to change things, to bring Godly reform. But we need to be about reforming our public theology itself, as it has not served us well. Saying, as most do, that we shouldn’t “mix church and state,” while true enough, simply isn’t enough. We must revisit our theology and see what cues and hints and stories are implicit (or sometimes even explicit) in our theological truths and see how they might equip us to be more faithful in our public vocations.

(Just for instance – in a lecture on Martin Luther, recently, a speaker I heard had just come back from the World Lutheran Federation’s commemoration of the 500th anniversary of the Reformation, and she reported how some were wondering how a deep commitment to being saved by grace alone (we can’t spiritually pull ourselves up by our own bootstraps, after all) might influence or even deconstruct market capitalism, that insists that we can and must pay our own way. I wonder what other economic, political, and social implications there are to the Reformation’s solas?)

Although James Smith is clearly situated as a professor at Calvin College in Michigan, a respected college run by the denomination that in the US is largely made up of descendants of the revival in Holland led by the late 19th/ early 20th century theologian, pastor, journalist, and political leader, Abraham Kuyper, Awaiting the King: Reforming Public Theology can be read by those unfamiliar with Kuyper’s terms and theological stances. In fact, the book draws heavily on broader Christian faith traditions (Catholic and Protestant) invoking much from Anglican Oliver O’Donovan and Duke University Methodist Stanley Hauerwas (who immersed himself in Catholic social teaching at Notre Dame and was influenced deeply by the Mennonite/Anabaptist tradition.) As is seen in all of Smith’s previous books, including the two earlier “Cultural Liturgy” titles, Desiring the Kingdom and Imagining the Kingdom, he is delightfully ecumenical.

That he is fluent in many different approaches to Christian theorizing about public life is seen wonderfully, by the way, in his sizable contributions to the five-fold conversation in Five Views on the Church and Politics edited by Amy Black (Zondervan; $19.99) where his response to Lutheran, Catholic, Mennonite, and African American/black liberationist authors indicate a profound awareness of the nuances of their own positions. I’ve reviewed this great book elsewhere at BookNotes, and I’m a fan. Smith’s chapter there about the neo-Calvinist “transformational” view is very, very good and he truly dazzles in his responses to the others.

That he is fluent in many different approaches to Christian theorizing about public life is seen wonderfully, by the way, in his sizable contributions to the five-fold conversation in Five Views on the Church and Politics edited by Amy Black (Zondervan; $19.99) where his response to Lutheran, Catholic, Mennonite, and African American/black liberationist authors indicate a profound awareness of the nuances of their own positions. I’ve reviewed this great book elsewhere at BookNotes, and I’m a fan. Smith’s chapter there about the neo-Calvinist “transformational” view is very, very good and he truly dazzles in his responses to the others.

One wonders how he does it; it is rare to find such widely-read leaders who are gracious about others, naming the strengths and weaknesses of other views, and yet remaining clear about their own firm tradition. In this, Smith has been shaped by his older brother in the cause, Richard Mouw, whose own intellectual memoir is called Adventures in Evangelical Civility: A Life-Long Quest for Common Ground, published by Brazos Press ($24.99.)

I suppose Smith has such pleasant ecumenical inclinations also because his own faith journey was hybrid – he and his wife were firstly Pentecostals, young students at a small, fundamentalist, Canadian Bible college, but learned through Francis Schaeffer of Dutch neo-Calvinist philosophers Vollenhoven and Dooyeweerd who taught at Kuyper’s Free University; this lead him to Toronto’s Institute for Christian Studies, the center of that intellectual tradition of reformational philosophy in North America, where he got a Master’s Degree, but soon earned a PhD under Catholic scholars at Villanova. He has appreciatively engaged the “Radical Orthodoxy” movement (and written books about that largely Anglican European tradition) and has spoken affectionately of artful worship renewal movements in the US lead by the likes of Wheaton’s late, great Robert Webber. (Smith has a splendidly interesting book  about how his Pentecostal leanings have influenced his work as a serious philosopher, called, with amazing wit, Thinking in Tongues.) He has served campus ministry organizations like the CCO and IVCF and has spoken in churches of varying denominations. His little handbook of Christian guidance for sturdy young Calvinists called Letters to a Young Calvinist attempts to broaden the horizons of Gospel Coalition types, inviting them to the longer and broader catholic tradition. Some of his varied influences and passion for robust contemporary application of faith to life can be seen in the collection of short pieces in Discipleship in the Present Tense: Reflections on Faith and Culture (Calvin College Press; $15.99.) It’s a personal favorite and we’re glad to stock it.

about how his Pentecostal leanings have influenced his work as a serious philosopher, called, with amazing wit, Thinking in Tongues.) He has served campus ministry organizations like the CCO and IVCF and has spoken in churches of varying denominations. His little handbook of Christian guidance for sturdy young Calvinists called Letters to a Young Calvinist attempts to broaden the horizons of Gospel Coalition types, inviting them to the longer and broader catholic tradition. Some of his varied influences and passion for robust contemporary application of faith to life can be seen in the collection of short pieces in Discipleship in the Present Tense: Reflections on Faith and Culture (Calvin College Press; $15.99.) It’s a personal favorite and we’re glad to stock it.

WATCH AND LISTEN TO SMITH AND THEN BUY THE BOOKS

If you’d like to watch and hear Jamie at his finest, listen to this less than half-hour message offered at Grove City College chapel this fall, (or an excellent, longer version at a evening lecture) both largely on his major thesis from the first of the Cultural Liturgies book, Desiring the Kingdom. I loved this lecture on the formative power of Christian liturgy offered at a worship conference at Trinity Episcopal School of Ministry in Ambridge, PA which he did when the second volume, Imagining the Kingdom, came out. Or, check out this lively talk to students at a Biology outdoor chapel, or this playful talk called “Putting on Christ Takes Practice.” Here he is at his own think-tank Cardus, doing a half hour lecture about postures for “Reforming Public Theology” and what Saint Augustine might have meant by his phrase suggesting we are “resident aliens.” as we live in harmony with other pilgrims.

Despite Smith’s wide learning and ecumenical dispositions, and wide-ranging philosophical footnotes, the new book is peppered with pop culture allusions and reflections on scenes from movies and musicals. The first chapter begins with a discussion of a less-than-stellar apocalyptic film starring Kevin Costner at his admitted worst. Jamie is able to translate the heady concepts of academics and philosophers into the lingua franca of most contemporary readers, whether they like John Updike or Death Cab for Cutie. Who won’t appreciate his analysis of scenes from The Godfather or his calling to mind viewing Man of La Mancha? Perhaps my biggest critique of the book is that I noticed no lines from Hamilton.

YOU SHOULD KNOW THIS MUCH ABOUT THIS THEME

Having said all that about it – it’s a book that takes very serious scholarship about public life and makes it interestingly readable and it is very ecumenical in its tone – it will be helpful, I think, to know this bit more about it: here is a very quick overview of a primary theme of Awaiting the King that I think will help you realize it’s significance and how it can help you life faithfully in your own embodiment of the gospel in your civic obligations. I hope I don’t muddy the waters, but inspire you to explore this question more carefully with Professor Smith.

Abraham Kuyper – the “every square inch” being claimed by Christ/worldview guy from the early 20th century – had two major theological themes that leads naturally to two different postures if taken individually. Smith thinks we’ve not taken both seriously enough.

COMMON GRACE

One theme of the Kuyper tradition is the lovely notion of “common grace.” That is, in God’s good world, our loving creator wants humans to flourish and good stuff happens among those of any and all religions. We can affirm – as Dean Enlow explained to the CLS gathering – good laws for public justice, whether they were crafted by atheists or Marxists or God-fearing fundamentalists. A good ball game (as many know these days) is a joy to behold and God takes pleasure in humans finding such pleasures. God allows for lovely stuff in our wondrous world and we are free to enjoy the goodness that flows upon us all, even if we remain dangerously alienated from God and sinfully disinterested in the glory of Christ.

One theme of the Kuyper tradition is the lovely notion of “common grace.” That is, in God’s good world, our loving creator wants humans to flourish and good stuff happens among those of any and all religions. We can affirm – as Dean Enlow explained to the CLS gathering – good laws for public justice, whether they were crafted by atheists or Marxists or God-fearing fundamentalists. A good ball game (as many know these days) is a joy to behold and God takes pleasure in humans finding such pleasures. God allows for lovely stuff in our wondrous world and we are free to enjoy the goodness that flows upon us all, even if we remain dangerously alienated from God and sinfully disinterested in the glory of Christ.

(My favorite study of this is found, by the way, in the fascinating little book by Richard Mouw called He Shines in All That’s Fair: Common Grace and Culture (Eerdmans; $15.50.) The book title is taken from the famous hymn “This Is Our Father’s World” written by a liberal Protestant minister and Mouw nicely  ponders if the line of the hymn is correct. He thinks it is, that God somehow is glorified in anything “fair” and good – from a finely executed golf putt to an aesthetically-mature painting to a trusting, happy marriage to a properly functioning electronic gizmo or government. Does God get glory when atheist scientists discover something good? When bohemian baristas roast a particularly good bean? Is God pleased when brutal communists get something right? When vile Hollywood sexists make a good film? Mouw says yes, and we should understand the goodness of common grace as a Godly grace of sorts so we have the framework for rightly praising such good stuff.)

ponders if the line of the hymn is correct. He thinks it is, that God somehow is glorified in anything “fair” and good – from a finely executed golf putt to an aesthetically-mature painting to a trusting, happy marriage to a properly functioning electronic gizmo or government. Does God get glory when atheist scientists discover something good? When bohemian baristas roast a particularly good bean? Is God pleased when brutal communists get something right? When vile Hollywood sexists make a good film? Mouw says yes, and we should understand the goodness of common grace as a Godly grace of sorts so we have the framework for rightly praising such good stuff.)

For those watching the sociology of religion, there is no doubt (no doubt at all) that Kuyper’s teachings about common grace have directly influenced modern evangelicalism, via the late 20th century rise of Christian colleges and Kuyperian writers within popular magazines from Christianity Today to Relevant to Image to Books & Culture. Our own story of being a Christian bookstore that stocks helpful or good secular books and music, for just one mundane example, raises many fewer eyebrows nowadays than when we first opened and garnered protests and boycotts (I kid you not) when we opened in the early 1980s. “We are all Kuyperians now” a church historian famously said of evangelical scholars a few years ago.

THE ANTI-THESIS

The other strong theme in Kuyper’s voluminous work, though, is what he calls “the anti-thesis.” That is, the Bible also teaches – alongside the claim that “this is our Father’s world” and, in the spirit of Kuyper’s common grace, we can happily enjoy much of our daily lives – that the principalities and powers are doing their best to deepen the rebellion happening on the planet. This isn’t just irreligious, but evil. To reject God’s ways and ignore God’s presence is worse than dishonorable and damaging. The gospel of Christ demands that we honor only one Lord and so any person, institution, social organization, business, cultural agency, political movement or society that doesn’t “kiss the sun” (as Psalm 1 poetically puts it, or “bow the knee” as Philippians has it) is bound for conflict with the only King of Kings. In other words, this emphasis reminds us, that a good school that is wholesome and safe and effective, but teaches students that God is not involved in the matters of daily life, is, most foundationally, a bad school. A body of artwork, no matter how excellently-produced, if it offers a world emptied of God is hostile. Any vision of marginalizing the authority of the Bible for life, any view that implies that humans dare be autonomous (“a law unto themselves”) or that any aspect of life is religiously neutral, is wrong-headed and worse.

The other strong theme in Kuyper’s voluminous work, though, is what he calls “the anti-thesis.” That is, the Bible also teaches – alongside the claim that “this is our Father’s world” and, in the spirit of Kuyper’s common grace, we can happily enjoy much of our daily lives – that the principalities and powers are doing their best to deepen the rebellion happening on the planet. This isn’t just irreligious, but evil. To reject God’s ways and ignore God’s presence is worse than dishonorable and damaging. The gospel of Christ demands that we honor only one Lord and so any person, institution, social organization, business, cultural agency, political movement or society that doesn’t “kiss the sun” (as Psalm 1 poetically puts it, or “bow the knee” as Philippians has it) is bound for conflict with the only King of Kings. In other words, this emphasis reminds us, that a good school that is wholesome and safe and effective, but teaches students that God is not involved in the matters of daily life, is, most foundationally, a bad school. A body of artwork, no matter how excellently-produced, if it offers a world emptied of God is hostile. Any vision of marginalizing the authority of the Bible for life, any view that implies that humans dare be autonomous (“a law unto themselves”) or that any aspect of life is religiously neutral, is wrong-headed and worse.

The old labor union song had a narrow focus, but they were right: we must choose what side we are on. The call from Joshua — choose this day! — or from Jesus, resounds even today and we must either honor God in Christ in all we do or we will be judged for complicity in the rebellion. Aslan is on the loose and we must reclaim the territory lost to the ravages of the rebel forces. Kuyper, the generous proponent of common grace for the common good also taught that we need distinctively Christian thinking shaping uniquely Christian organizations to stand against the onslaught of anti-Christian pressures and God-denying forces in every sphere of our complex world.

BOTH-AND (NOT EITHER OR)

Maybe Kuyperian thought isn’t this simple. The hefty hardback Contours of the Kuyperian Tradition: A Systematic Introduction by Craig Bartholomew (IVP; $40.00) is a highly recommended, wonderfully detailed study of Kuyperian cultural renewal and the theology that funds it. For those really interested in where Smith is coming from, this explains a part of it.

Maybe Kuyperian thought isn’t this simple. The hefty hardback Contours of the Kuyperian Tradition: A Systematic Introduction by Craig Bartholomew (IVP; $40.00) is a highly recommended, wonderfully detailed study of Kuyperian cultural renewal and the theology that funds it. For those really interested in where Smith is coming from, this explains a part of it.

But, still, at the risk of oversimplification, Smith’s Awaiting book can be described as a deep reflection on political theology that allows us to have a public faith that is informed by both common grace and the antithesis.

IN LIGHT OF CLASSIC ENLIGHTENMENT LIBERALISM

In other words – again citing one of Smith’s mentors, Richard Mouw – we are “called to holy worldliness.” We can both affirm much of liberal democracy and yet we may not be under any illusions that truth emerges from some sacred counting of votes. We can be glad that individuals matter but cannot be under any illusions that all that matters in individual liberty. We can be glad for the modern state and all that we’ve benefitted from, but government based on autonomy from God will finally be a curse upon us. Who doesn’t want to be thoughtful and reasonable, but the pompous Enlightenment that privileges only secularized, rationalism is woeful. (It is significant that Kuyper called his political party the Anti-Revolutionary Party, responding to the radically anti-Christian violence of the French Revolution.) This modern world is not friendly to a deeply construed Christian worldview; as modernity gives rise to post-modernity, we must be discerning, aware of idols and ideologies that come along with the times, that are in the air, like it or not.

This concern about reductionistic, rationalistic views of truth that marginalizes tradition and faith is the anti-Enlightenment project that has caused many of our deepest thinkers to ponder how to formulate a pluralistic and principled Christian witness, creating a culture that isn’t a theonomy – heaven cries out against crusades and jihads! – and yet doesn’t arrange society in some dualistic fashion that keeps faith private while public life comes from reason and science. This general approach doesn’t want to keep faith out of the public debates but isn’t trying to take over, either. In this sense, it grapples with classic liberal democracy, surely, though, without wanting to return to any medieval view of the Divine Right of Kings or the Church running “the Holy Roman Empire.” Heaven forbid! But what does it mean to be in this world that declares that the politics and laws of the land are separated from God’s Word — without falling for the seductions of such secularizing pressures?

This is the question that vexes the great recent philosophers Alister McIntyre and Charles Taylor and it vexes common preachers like Will Willimon in recent classics like Resident Aliens. Lesslie Newbigin addresses it often, insisting that the gospel makes public claims, not merely personal/private ones and that this is “foolishness to the Greeks.” Although with different answers, it is the overall concern of James Davison Hunter and his famous Oxford University Press book To Change the World The Irony, Tragedy, and Possibility of Christianity in the Late Modern World. Of course N.T. Wright is asking this question in most of his work. There are no cheap answers and we must learn from the best thinkers of our time.

POSITIVE PLURALISM

Some of our best pastors are trying to help their congregants struggle with a balanced faithful posture. I think of the popular gatherings sponsored by Q Ideas which brings a variety of voices to the table to help us ask good questions about our cultural mission and how many local churches or para-church groups sponsor simulcasts with groups all over joining in these national conversations. I recall us selling books earlier this year as Tim Keller in New York hosted an event with John Inazu reflecting with New York Times columnist Nicholas Kristoff on Inazu’s wonderful book Confident Pluralism: Surviving and Thriving Through Deep Differences. I think of the courageous work of Os Guinness, publishing books like The Case for Civility: And Why Our Future Depends on It which offered proposal that tweaked both the religious right and the secular left, inviting all to a better system of cooperation and how congregations studied it together. It even dawns on me that I’m speaking at a conference in Pittsburgh next week called “Embodied Community” organized by Western Pennsylvania folks who learned in the 1970s about Kuyper and his notions of principled pluralism – a social theory that invites all to live deeply out of their own principles but honors God’s desire for a public square that is congenial to those of any faith or none, offering justice for all. Our favorite Christian think-tank in DC, The Center for Public Justice works behind the scenes helping citizens reflect well on the meaning of faith in public life, both honoring deep differences and promoting a mechanism to allow for religious liberty amidst principled pluralism. These gentle reforming initiatives have emerged among folks that seem to get both “common grace” and “the antithesis.”

All of us fumbling forward along the way to the New City who know that we are “called to holy worldliness” need James KA Smith’s deeper insight found like manna in Awaiting the King. In it he is asking us to consider how to live into a vision of “appropriate pluralism as a Christian public philosophy.” He is asking us to learn this from church; indeed, the local Body is to be itself a sort of polis that shapes us for the life of the world, for the common good. We are to “seek the peace of the city” and all that.

And so, we’ve got work to do. God sends us happily into a world full of grandeur, full of common graces, gifts given freely to all. What joy.

But we live in a world that is broken and, the Bible reminds us, in many ways in fundamental opposition to the rulership of Christ. We do not think that the Christendom model of a churchy take-over of public life is right, so even as we resist the privatization of faith we certainly don’t mean to imply any Christian versions of jihads or theonomies.

How then to parse all of this in-but-not-of thinking while we awaiting the final sorting out done by God in God’s own final reckoning? How do we live in the tension of being homesteaders and pilgrims? Of the presence of the Kingdom in a fallen world? How to we hold together common grace and a realization of the anti-thesis in every sphere of life? What does it look like to become worldly saints? How do we live out our call to holy worldliness? What sort of churches foster such questions and what sort of formation will shape within us the character to do so? How do we actively await the true hope of the gospel, the summing up of all things in the new heavens and new Earth? And, not unimportantly, given the hardships, can we have fun doing so?

These three books in the “Cultural Liturgies” trilogy, Desiring the Kingdom, Imagining the Kingdom, and, now, at last, Awaiting the King, will help by probing deeply our radical convictions as Westerners. Smith’s ecumenical Kuyperian combo of common grace plus the antithesis shaping a vision of public life is offered – helping us get it better than we have in our previous thinking, re-shaping our hopes for the good, and guiding our actual habits and practices. It will help us navigate what he calls “the craters in the gospel” and become more wholistic and attentive, which, in turn, will help us resist secularizing, classic liberalism that erodes truth and goodness.

These three books in the “Cultural Liturgies” trilogy, Desiring the Kingdom, Imagining the Kingdom, and, now, at last, Awaiting the King, will help by probing deeply our radical convictions as Westerners. Smith’s ecumenical Kuyperian combo of common grace plus the antithesis shaping a vision of public life is offered – helping us get it better than we have in our previous thinking, re-shaping our hopes for the good, and guiding our actual habits and practices. It will help us navigate what he calls “the craters in the gospel” and become more wholistic and attentive, which, in turn, will help us resist secularizing, classic liberalism that erodes truth and goodness.

TEACHING ABOUT O’DONVOAN AND OTHERS

As we’ve said, he does all this largely through engaging with the thinking of other key scholars whose names you should know, such as Oliver O’Donovan. I find O’Donovan dense, so I’m really glad for this assist, and you will be too.

For instance, Smith explains,

Part of the work of public theology, Oliver O’Donovan suggests, is to offer a theologically inflected genealogy of our political institutions and rites in Western liberal democracies. In this mode, the public theologian is an institutional genealogist, uncovering the perhaps hidden (perhaps embarrassing?) history of secular society. When and where the Christian theological impetus for political realities is shrouded in ancient history or actively forgotten for revisionist reasons, the public theologian can be prophetic simply be being an organ of collective memory. The public theologian unveils the family history of liberal democracy with all of its religious grandmothers and Christian uncles. Perhaps this helps explain to us ourselves. Perhaps it even invites us to image ourselves otherwise.

RACE, RACISM, AND THEORIES OF RACE

I simply must add one more important aspect of this book, which I trust will show its exceptional relevance. Although he doesn’t cite the discussions about mass incarceration’s implicit racism or books like the stunning Just Mercy by Bryan Stevenson, Smith enters a conversation about racism in the United States, especially, as an example of how to think about institutions, systems, injustices and how worldviews and social imaginations cause us to envision others. In this project he is not just inviting us to racial reconciliation or to work for  faith-based community development a la John Perkins (good, good, good as those projects are.) In Awaiting the Kingdom Smith engages in serious academic discourse about some of the finest Christian scholars of race writing these days, namely Willie James Jennings, author of The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (published by Yale University Press; $27.95) and Brian Bantum and his book Redeeming Mulatto: A Theology of Race and Christian Hybridity (published by Baylor University Press; $29.95.) Jamie does this to show the failures of much liturgy and how whiteness is a social construct that has impacted how we approach God, worship, and church. It is demands some serious study, but it will help us get beyond sloganeering and shallow moralism. It’s a radical/radix kind of approach.

faith-based community development a la John Perkins (good, good, good as those projects are.) In Awaiting the Kingdom Smith engages in serious academic discourse about some of the finest Christian scholars of race writing these days, namely Willie James Jennings, author of The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race (published by Yale University Press; $27.95) and Brian Bantum and his book Redeeming Mulatto: A Theology of Race and Christian Hybridity (published by Baylor University Press; $29.95.) Jamie does this to show the failures of much liturgy and how whiteness is a social construct that has impacted how we approach God, worship, and church. It is demands some serious study, but it will help us get beyond sloganeering and shallow moralism. It’s a radical/radix kind of approach.

He explores this, in fact, somewhat in light of the sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, who brought us the notion of “ethnography” – see the thoughtful little book Smith edited by Christian Scharen called Fieldwork in Theology: Exploring the Social Context of God’s Work in the World. It is above my pay grade to describe all this but I gather this is in response to some very important voices of previous decades such as John Milbank and that Radical Orthodoxy movement. I mention this not only to illustrate that Smith is not unaware of the most burning issues of the day –racism, white privilege, criminal justice – but to show that he invites profound thinking on such issues informed by deep scholarship, not just sloganeering or moralism. This is important, as his project, again, is to take seriously the ways cultural habits and social realities form us, how new stories and new habits are needed among us to shape new desires, and how institutions and cultural forces must be taken into consideration as we learn to imagine a new Kingdom, and await our coming Kingdom. That is, to bear witness to God’s reign in helpful ways we have to think more deeply. This book helps us immensely in this huge process.

ON A JOURNEY TO THE NEW CITY

Smith ends this weighty book with more looks at Augustine’s City of God (a constant throughout his work) and some of the old African Bishop’s letters and prayers. And he reflects on Hans Boersma’s fascinating book Heavenly Participating: The Weaving of a Sacramental Tapestry published by Eerdmans a few years ago. In that book Boersma – a good friend of Jamie’s – admits that, like many of us in Kuyperian circles, have spent great energies trying to get evangelicals, especially, to renounce an unhelpful otherworldly piety, but that, perhaps, the pendulum has swung too far in the other direction, that far from being disinterested in the goodness of creation, many young evangelicals hardly have any sense of heaven. Whether this is so or not, Smith worries, too, that the notion of the “heavenly city” has been eclipsed.

In conversation with Boersma, Smith writes,

It is precisely our citizenship in the heavenly city that guides our commingling with the early city; it is our pilgrimage toward the heavenly city that helps us navigate the terrain of a fallen-but-redeemed creation.

This is not rocket science, I suppose. We are pilgrims on a journey, but we are to be responsible salt and light and leaven here, now. But given the foolish theologies and hard pressures of this modern world, and the crisis of the public now being experienced world-wide, seen most obviously in the chaos of the current White House and the complicity in white evangelicalism for it, we need, as much as ever before in our lifetimes, a good, good dose of this reasonable, wise, fruitful consideration of reforming public theology. And then we have to figure out how to practice it, recalling, rehearsing, slowing allowing the virtue of this recalibrated love to bubble up inside us and spill out into an embodied lifestyle.

If Awaiting the King helps us await actively and well, it will be worth working through. If it helps church leaders, pastors, Christian educators, campus ministers and youth leaders help others become better citizens, thanks be. And if it – please God! – helps our thought leaders and theologians and seminary teachers and political ethicists and Christian scholars truly reform public theology, that will be a double blessing, beneficial for the long haul. Thank God for Baker Academic, James K.A. Smith, and his important contribution in this final volume of his important Cultural Liturgies trilogy.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% Off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313

read@heartsandmindsbooks.com

717-246-3333