Recently, a few sharp customers on varying places on the spectrum of views about the theology of the atonement have asked me to “weigh in” on new ideas, old ideas, classic doctrines and emerging newer perspectives about the theology of the cross. (I recommend Scot McKnight’s A Community Called Atonement [Abingdon; $17] for a great introduction to various schools of thought and views on the meaning and implications of Christ’s redeeming work if you are unaware of the blazing debates about this these days.) Many know that we carry all kinds of books and encourage reading widely, discussing, being open, showing considerate consideration to brothers and sisters with new insights or troubling concerns. (Remember that David Dark book I highlighted a few weeks back, The Sacredness of Questioning Everything [Zondervan; $15.99.]) I think we have to be open to hearing many voices, hosting hard questions, eager for new, faithful formulations, and we carry a real diverse selection here at the shop.

Of course this doesn’t mean we can just throw out any old thing in preference to the new. I’m turned off when newer theologians cheaply insist that the classic view of Christ on the cross pays for our sins is just so much bloody nonsense, leading to wars and child abuse. And I’m irked when those who disagree with more nuanced and thoughtful articulations of those concerns pass it off as a mere desire for faddishness or being offended by the blood. (Could it be that those who struggle with this are well-intended and perhaps onto perhaps a partial truth?) For instance, in a blurb on the back of a book I’m about to describe, a reviewer says that this book “defends (against) reprehensible attacks” against traditional understandings of the cross. When new theologians quest for new ways to get stuff said, it isn’t necessary or helpful, in my view, to call them names or to say they are reprehensible. I sometimes don’t know who is worse, the edgy new guys or the stuffy old ones. As we recall Christ’s great love shown in His passion acts (and mandates–the Maundy Thursday call to wash each others feet!) we can create good spaces for healthy conversation and charitable dialogue. That is why I liked the title of McKnight’s book–we are a catholic community piecing together the best ways to describe the deepest mysteries; what Lewis calls in Narnia the “deeper magic.”

And, of course, the cross is described as a great mystery. Who can fathom it all? Even those of us who hold traditional theology surely ponder sometimes, don’t we? Why o why? The great hymns ask the question. Sure, we can answer it wrongly, we can un faithfully dismiss the witness of the Scripture, but to ponder, to study, to float ideas and suggest better ways to speak about the dearest things of God’s gospel, is not reprehensible. Shame on Crossway for publishing such a blurb.

Yet, the historic creeds and doctrines of the church are being re-considered, sometimes with the best of Spirit-driven motivation, perhaps sometimes not. Sometimes out of a legitimate need to open up answers to hard questions, unsettled ponderings, and sometimes with less than commendable answers. That has been a huge erosion of traditional knowledge in our churches. There are many books on the cross and the atonement, from various perspectives and denominational traditions, many from which I’ve learned. I’m open and eager to study this many-faceted jewel from any side I can (and will list a few suggestions later if you share this open-minded eagerness.) Can liberals learn from conservatives? Can those with traditional convictions read with charity the newer views? We hope so…

I hope this week-end, as you ponder the cross, the darkness of Good Friday, the ponderous depth of Holy Saturday, and the glory of the Resurrection emerging from the horrible death penalty and State execution of the cross, that you may find yourself wanting to know more about the reasons Christ died, how to properly understand that extraordinary transaction, knowing well the ancient ways of formulating it, learning to say it in the midst of a post-Christian, postmodern culture. May you stand again at the foot of the Cross, struck as most of us are this time of year, by the centrality of it all.

***

Another quick story: just the other day a regular customer, an African American church leader, was looking for books on the blood of Christ (interestingly, the blood is mentioned in the New Testament more than the cross.) I showed her a book that mentioned “penal substitution” and she asked what that meant. As I explain the typical view that Christ somehow took the punishment we deserved, paid a penalty, averted God’s wrath that was due us, she nodded in obvious awareness. “Some Christians don’t believe that?” she asked incredulously. “No,” I noted, “there are those who think that that way of saying it, that metaphor of wrath and punishment and courtroom images, isn’t fully Biblical and isn’t the most helpful way to describe God’s love and Christ’s willingness to give Himself.” “Lawd-have- mercy” she replied. Indeed. For centuries common Christian folk have read their Bibles and heard verses read out loud and sung hymns and it was perfectly clear that the “he died for my sins” view was not just cooked up by Ansalm, but is deeply rooted in the whole Biblical narrative. To explore new ways to get it said is one thing; to deny the obvious Biblical data…well.. Lord have mercy.

Or, as the Book of Common Prayer puts it:

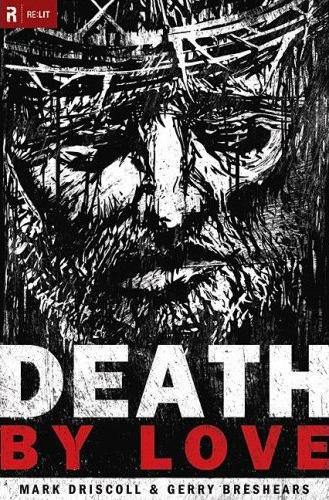

Death By Love: Letters from the Cross by Mark Driscoll and Gerry Breshears (Crossway; $19.99) is an extraordinary book which upholds in blunt and non-negotiable language, the historic Reformation perspective on the cross. I am not a Mark Driscoll fan, I’ve not loved his other books, I think he is wrong-headed about some things, and his youtube sermons betray an arrogance and pride that he himself has sometimes admitted to. Yet, yet, this is a book that brought me to tears, struck me as very, very insightful, and despite the occasional harsh note, is a book rooted in a very deep sense of pastoral care. The format is extraordinary, and serves several good ends. Let me tell you about it.

$19.99) is an extraordinary book which upholds in blunt and non-negotiable language, the historic Reformation perspective on the cross. I am not a Mark Driscoll fan, I’ve not loved his other books, I think he is wrong-headed about some things, and his youtube sermons betray an arrogance and pride that he himself has sometimes admitted to. Yet, yet, this is a book that brought me to tears, struck me as very, very insightful, and despite the occasional harsh note, is a book rooted in a very deep sense of pastoral care. The format is extraordinary, and serves several good ends. Let me tell you about it.

Each chapter begins with a riveting description of a friend of his, a person in his congregation. Several have faced abuse. One was a child molester. One was a sex addict. Another self-righteous and controlling, joyless and rigid with his upright family. One has a wife with a brain tumor while another holds deep hatred for a relative. One was raped, another fears hell. One just wants to know God. Oh my, how I wish every pastor knew his or her flock this well, able to know so intimately and write with such care, about the horrors of life as experienced by folks in this broken world. Driscoll and his co-author describe these hard situations without extra sensationalism, but he doesn’t water down the problems or his proposals. Their language is terse and realistic and candid. Driscoll doesn’t beat around the bush.

Then, there is the heart of each chapter, a pastoral letter he wrote to this person showing how a particular doctrine, aspect, or formulation of the cross can be the very truth that f

rees this parishioner from his or her torment. And this is where it gets very interesting: Driscoll has absolutely no interest in psychology or in counseling or in strategic empathy as a supportive helper in self-discovery. He is a preacher, a neo-Puritan pastor, a working theologian. That is, he is convinced that appropriating the doctrines of justification, atonement, propetiation, imputation of righteousness, Christus Victor, ransom, Christus Exemplar, reconciliation, and such are the keys to healing, hope, and renewal. In some cases he is exceedingly blunt with little interest in sugarcoating the hard truth; I suspect that not all of these letters were well-received. He regularly says that he loves the one he is writing to, says dear and tender things, and occasionally reminds us that this letter isn’t (of course) the first thing that he has said. (Those schooled in traditional pastoral counseling will be aghast, as I was, at times, but, again, we can know that these are offered in the context of broader pastoral relationships and true friendship.) These letters aren’t the start but the height of his pastoral counsel, after much hand-holding, meetings, confessions, tears and prayer. Yet, it is no-nonsense, straight-up, Biblical teaching, confident that an appropriation of historic, orthodox theology will make all the difference.

To make this book all the more moving, there are very strong black and white sketches of the person to whom the letter is written, each with a hint or smear of red. The chapter headings are in red ink as well, giving this a classy feel, despite the intense drawings and heavy topics.

To make this book all the more moving, there are very strong black and white sketches of the person to whom the letter is written, each with a hint or smear of red. The chapter headings are in red ink as well, giving this a classy feel, despite the intense drawings and heavy topics.

Wow. I have a hunch that typical fundamentalists would not write these letters; in my experience many older-school fundamentalist Protestants would be afraid to name the sins (especially those of a sexual nature) and would be moralistic and glib in proof-texting verses about proper behavior, as if that alone would shame the person into faithfulness or bring sentimental comfort. More evangelical pastors and many liberal Protestants and Catholics may believe much of this (although some clearly will not) but it is my sense that many church leaders are much more accommodated to the neo-Freudian worldview and would use more pop psychology than Biblical theology if they had these conversations. (Some, I would guess, would merely recommend a therapist, although Catholics might utilize the sacrament of confession/reconciliation.) Although these doctrines are commonplace for those who know classic historic theology, I know of pastors who have never taken a single class on these doctrines. It is bracing to see a pastor use this stuff in this way.

I am not sure I would commend writing letters like each of these although a few are brilliant and I devoured them, thinking and praying and reflecting on them a lot. I might want to qualify things a bit, maybe soften the insistence a bit, although that is not Driscoll’s style, and I am hopeful that he knew the folks well enough to be confident he was writing what needed to be said, in a manner that didn’t offend needlessly. I am not sure if Driscoll even really wrote all these, or if they are beefed up for the book, with a bit of understandable creative liscense.

Still, I stand in great appreciation for at least three things about Death By Love: Driscoll’s Seattle church clearly has attracted people with deep, deep wounds, and as a pastor he knows these folk as friends. Thank goodness for that. He believes that theology is life-changing and that teaching these central truths is not tangential but central to the calling of being a pastor. Right on. And he shows that there is not just one aspect to the glorious cross, but many ways that the Bible speaks of and our best theologians have learned to say what is so good about Good Friday. This bombastic punk pastor knows this, that there are many facets to the jewel of the cross, and that we can draw on various doctrines and explanations, with many ways to explain and appropriate the core truth of God’s redeeming grace. If we teach them well, he shows, they become not arcane insights for the weirdos who may be theologically-minded, but become avenues of healing, wholeness, growth and sanctification. Driscoll the popularizer of heavy theology is also Driscoll the serious pastor. I commend him for this important effort, and recommend his book to anyone who wants a solid introduction to historic, conservative doctrine, applied afresh amidst the very, very broken world of those who are sinners and those who have been sinned against. Which is, of course, each and every one of us.

In the next post, I will list a few more books on the cross that I’ve been taken with lately, a few classics, a few controversial ones, and one or two suggestions for those starting this journey of understanding the apex of our Lenten journey.

Good post. Stott’s book on the cross put a lot of things together for me, plus some others. An old

book, that he later tweaked after reading Stott, is

“Interpreting the Atonement” by Robert Culpepper.

I’m sure you can get it from a used bookstore.

Fleming Rutledge is working on a book about the cross.

Excellent. I bought this for a dear friend recently.

Thank God for the Cross.

May it grow larger and grace grow bigger as we face the enormity of our sin.

Thanks be to God!

I just finished a Penal Substitution debate, if anyone is interested:

http://catholicdefense.googlepages.com/psdebate