In my last post, naming books about reading, our technological culture, media and so forth, I was happy to announce the paperback release of the fine bit of literary criticism (such a stodgy word for it) by Wendell Berry, Imagination in Place. It was all I could do not to mention his brand new one, which is oh-so-similar, one that I am prepared to rave about. I didn’t want such an important revelation to get lost in that paragraph.

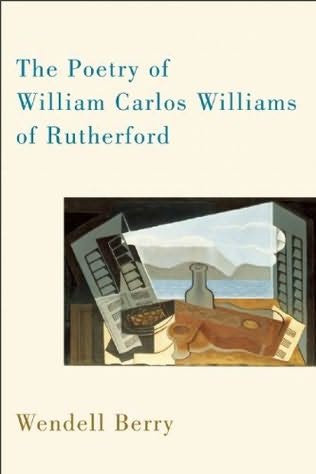

So, now, a proper announcement. Wendell Berry has a brand new book, and its first half, which I have read, is clear as a bell and as solid as Kentucky limestone. It is truly fascinating, especially if you like Wendell talking about his own life as a writer, or if you like the poetry of William Carlos Williams. It is called The Poetry of William Carlos Williams of Rutherford (Counterpoint; $24.00.)

So, now, a proper announcement. Wendell Berry has a brand new book, and its first half, which I have read, is clear as a bell and as solid as Kentucky limestone. It is truly fascinating, especially if you like Wendell talking about his own life as a writer, or if you like the poetry of William Carlos Williams. It is called The Poetry of William Carlos Williams of Rutherford (Counterpoint; $24.00.)

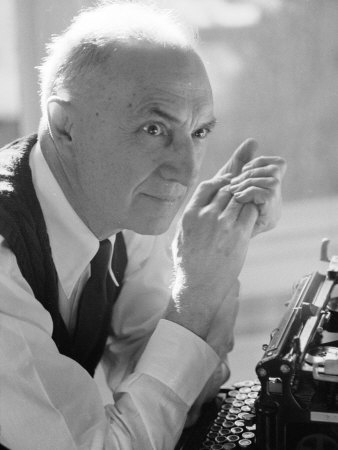

The title itself is revealing and significant. Any high-school kid should at least know the name William Carlos Williams and those who have followed our blog know that we have promoted the wonderful essays on literature and character and social change by the Harvard professor, Robert Coles, and how Coles holds up Williams as a great writer who related literature to his day job, being a family doctor, in his urban setting. You can see where this is going—imagination in place! William Carlos Williams of Rutherford New Jersey? Berry has the eyes to see (and apparently those schooled in mid-20th century poetry know this) that WCW was, in fact, an oddball of sorts: he wrote about common people in a real location, allowing his participation in the local neighborhood–his work, his friends, his neighbors, his church–to influence (indeed, to become to subject of) his extraordinary poems. He was belittled for this by the hot shots, and this is, of course, a part of the story. Berry took great inspiration in this (I wondered, to be honest, why William Carlos Williams wasn’t in Imagination in Place as he seemed to exemplify that book’s thesis. Now we know—Berry was doing a whole book on this same theme that structures Imagination in Place, using WCW as the great example.)

I should say that it is only my lack of vocabulary that causes me to say Berry is “using” WCW as an “example.” Berry is more subtle than that, more nuanced and insightful and kind. But, still, the Borger short-hand being what it is, I’d explain the book like this: he illustrates how a sense of place (in this case Rutherford and Paterson NJ) shaped and influenced and became fodder for the great work of this too often misunderstood poet and doctor, the fascinating William Carlos Willliams. And how Berry himself does that in his own Kentucky homeland, drawing inspiration from Dr. Williams.

It hasn’t directly come up yet in the book but it is obviously significant that both of these poets are bi-vocational. Both Berry and Williams have other jobs, working with their hands, in farming and pediatrics, respectively. So not only does their place in a locale shape their poems and stories, but their day jobs do, too. (This is one of the matters explored by the aforementioned Robert Coles, in Call of Stories: Teaching and the Moral Imagination and Handing One Another Along: Literature and Social Reflection and in his Lives We Carry With Us: Profiles of Moral Courage. Somewhere he tells of using William Carlos Williams in his own work teaching med students. Do any ag schools use Berry’s poems or short stories, I wonder? One can hope.)

and stories, but their day jobs do, too. (This is one of the matters explored by the aforementioned Robert Coles, in Call of Stories: Teaching and the Moral Imagination and Handing One Another Along: Literature and Social Reflection and in his Lives We Carry With Us: Profiles of Moral Courage. Somewhere he tells of using William Carlos Williams in his own work teaching med students. Do any ag schools use Berry’s poems or short stories, I wonder? One can hope.)

And so, The Poetry of William Carlos Williams of Rutherford is a book- length treatment, in short, wonderful chapters, of Berry’s own appreciation and analysis of Williams, and his writing about his place.

Did you know that many of the most prominent professional poets of his generation moved to Europe, or at least traveled there much, reveling in their leaving. In a related corner of the zeitgeist, it was said that the only poetry that matters was that of the city; Berry was seriously warned that his literary career would abort if he returned to Appalachia. This has been reported in other Berry books how he himself was discouraged from moving back to Kentucky (see the chapter “My Friend Hayden” in Imagination in Place about the New Hampshire farmer-poet who was an example to Berry that one could be a successful writer and not live in the urbane and sophisticated circles of New York or New Haven.) Well, leaving was the thing, and they mocked Williams for staying. Berry explains it well, and it continues to be an important matter, and will continue to be so for many of us.

Similarly, and perhaps of interest to some some BookNotes friends who work at colleges or in college ministry, Berry notes, without much judgment, that most college professors have, in fact, needed to leave their own regions and kin to take up careers in the modern college town, which has an effect on the kind of research and work they do. He notes that most professional poets these days are hired at universities, and he writes,

Unless university poets are actually from some place in particular, and unless they have the good fortune to be employed somewhere near their homes, they tend to be careerists and migrants, without local knowledge or affections of loyalty, like their professional and specialist colleagues. They are therefore under pressure to conform to, and they have no immediate reason to resist, the industrial order represented by their university. They, like their critics, are inclined to think that the arts are under obligation to keep up with the times, and to conform to industrial values and advances in technology. This is not a quarrel I wish to bring against anybody in particular, and I know there are reasons and also exceptions…What I am describing, however, is too easily possible in the modern universities. The tendency is toward careerism, personal displacement, scientific reductionism, and technological determinism. Williams saw this tendency, understood it, feared it, and resisted it.

One of the ways he did this, of course, is he stayed put, did his work, wrote his stories and poems and essays, situated. Berry puts it simply, ” He lived, practiced medicine, and wrote his poems in the same place all his life. He lived by the terms of a community involvement more constant, more intimate, and more urgent than any other notable poet of his day.” He continues, “He watched his neighbors and his patients, who often were the same people, with the keenest interest, affection, and amusement, and often enough with dismay.” (One hears echoes of Eugene Peterson, here, even how he learned to be a better pastor by reading about the ordinary people in novels.)

One of the ways he did this, of course, is he stayed put, did his work, wrote his stories and poems and essays, situated. Berry puts it simply, ” He lived, practiced medicine, and wrote his poems in the same place all his life. He lived by the terms of a community involvement more constant, more intimate, and more urgent than any other notable poet of his day.” He continues, “He watched his neighbors and his patients, who often were the same people, with the keenest interest, affection, and amusement, and often enough with dismay.” (One hears echoes of Eugene Peterson, here, even how he learned to be a better pastor by reading about the ordinary people in novels.)

This is the kind of doctor and poet William Carlos Williams was, and the kind of poet and citizen Wendell Berry is. And it is, apparently, more rare than you might think. (Come to think of it, I wish

I had a doctor—let alone a poet—who watched me with “keen interest, affection, amusement” and, heck, I’d even take dismay. I don’t think our current doctor remembers my name and sure doesn’t write any poems about me. But that’s another story.)

Berry writes,

William Carlos Williams “was a poet determinedly and conscientiously local. Some writers, comparatively few, have assumed the burden both of local subject matter and local stewardship, and some–most–do not. Thoreau did, Henry James did not; Faulkner did, Hemingway did not; Williams did, Elliot did not. By noticing this I mean to imply no blame. The difference is nonetheless significant, and it must be taken into account if we are to deal justly with William’s poetry. As Booker T. Washington counseled his own people to do, Williams cast down his bucket where he was.

Well, I could say more. There is a chapter called “The Problems of A Local Commitment” and another called “Local Adaptation.” And–you should know as you consider if this book will fully interest you–there are a dozen short chapters, each about an aspect of Williams’ poetic styles. There are chapters called “Line and Syntax” and “Measure” and “The Structure of Sounds.” I am not schooled in poetry at all and frankly am not as interested in it as you might suppose. But this book is already important to me, a tutorial by a master poet with values I trust, using a fine and important writer as an example of these word-smithing details. Consider this new book another Berry-esque essay about much that is wrong in our culture, or much that is right about his faithful, populist/agrarian vision, which I suppose it is. But it is, also, a rare study of a particular poet, and a mini-course on poetry, what it is, how it works, and how it is situated, at least in American culture. (There is one fantastic chapter—I jumped ahead to read it—called “Williams and Elliot” that is really thought-provoking, especially showing how both poets concluded that their times were “wastelands.”) I think most of us could use the refresher course in poetics, and who better to teach us?

Well, I could say more. There is a chapter called “The Problems of A Local Commitment” and another called “Local Adaptation.” And–you should know as you consider if this book will fully interest you–there are a dozen short chapters, each about an aspect of Williams’ poetic styles. There are chapters called “Line and Syntax” and “Measure” and “The Structure of Sounds.” I am not schooled in poetry at all and frankly am not as interested in it as you might suppose. But this book is already important to me, a tutorial by a master poet with values I trust, using a fine and important writer as an example of these word-smithing details. Consider this new book another Berry-esque essay about much that is wrong in our culture, or much that is right about his faithful, populist/agrarian vision, which I suppose it is. But it is, also, a rare study of a particular poet, and a mini-course on poetry, what it is, how it works, and how it is situated, at least in American culture. (There is one fantastic chapter—I jumped ahead to read it—called “Williams and Elliot” that is really thought-provoking, especially showing how both poets concluded that their times were “wastelands.”) I think most of us could use the refresher course in poetics, and who better to teach us?

Look. I know some of my readers, like myself, value Berry’s wonderful stories (Hannah Coulter may be an all time favorite novel of both Beth and me, as is Jayber Crowe.) And, even more, I appreciate his social vision as worked out in his careful, studious essays. The man did a sit-in to protest mountaintop removal at the Kentucky governor’s office last month (at my facebook, I linked to a youtube interview with the tired protester, saying he should have done it years before.) I am mostly drawn to his call to care for land, to reject government shenanigans, to live as God’s steward of creation. His wonderful essays on food have been brought together in a profound collection called Bringing It To The Table: On Farming and Food, mature writing that is just so relevant for all of us. He attends a small country church, has been shaped by Methodist hymns and his King James Bible, and he makes tons of common sense, following the teachings of Jesus as best he can. Sex, Economy, Freedom and Community is a fabulous starting anthology, so I’m not always a quick to think about his poetry.

But this, this poetry, this is what sustains and shapes the man. If you care about Berry, really, you should be interested in this book. He tells us, movingly, I think, on the very last page, once again, what has been the theme of the book about this poet from North Jersey:

It has been so important because Williams’ place was as marginal in its way as my own, and he devoted his life and art to it, not looking away or yearning toward some “better” place. Of all the writers known to me, Williams dealt most directly and explicitly with the complex cultural necessity of an ongoing, lively connection between imagination in the highest sense and the ground underfoot. Nobody had confronted more steadily the difficulties of such an effort in the face of the encroachments everywhere of industrial values, industrial exploitation, and the consequent loneliness of industrial individualism. For half a century his example has been always near to my thoughts, his poems always

at hand. I have taken from them an encouragement and a consolation that I have

needed and could not otherwise have found.

It may be a bit incongruous, but now seems a great time to celebrate two other recent and much-commented upon poetry volumes, by poets whose writings are not at all like Mr. Berry’s. One is rather unknown, released by an indie press started by a dear friend. The other was just released by a very prestigious press after having garnered an important award. I do not know the first poet, but the second is a long-time friend.

Both deserve huge accolades and we are happy to promote them.

Contingency Plans David K. Wheeler (T.S. Poetry Press) $14.00 Wheeler has quite a gathering clan of fans and his work shows up at cool places like the Burnside Writer’s Collective, TheHighCalling blog, and has been included in an important regional volume (The Pacific Northwest Reader, published by Harper/Delphinium.) He blogs at davewritesright.blogspot.com and, as you’ll discover, he is a fascinating fellow, a musician, essayist, and a very wonderful poet. Contingency Plans is a great book at a great value—lots of solid poems, on all kinds of topics. Poet Oliver de la Paz writes of it “These are poems of great spiritual crisis and consequence, where the dark night of the soul is a rugged rucksack shouldered by the poet. But the wilderness resounds with the voice of a choir and the wearying road can always beckon you home.” How can you not want to read something described like that?

Contingency Plans David K. Wheeler (T.S. Poetry Press) $14.00 Wheeler has quite a gathering clan of fans and his work shows up at cool places like the Burnside Writer’s Collective, TheHighCalling blog, and has been included in an important regional volume (The Pacific Northwest Reader, published by Harper/Delphinium.) He blogs at davewritesright.blogspot.com and, as you’ll discover, he is a fascinating fellow, a musician, essayist, and a very wonderful poet. Contingency Plans is a great book at a great value—lots of solid poems, on all kinds of topics. Poet Oliver de la Paz writes of it “These are poems of great spiritual crisis and consequence, where the dark night of the soul is a rugged rucksack shouldered by the poet. But the wilderness resounds with the voice of a choir and the wearying road can always beckon you home.” How can you not want to read something described like that?

Comedian and memoirist Susan Isaacs–whose book Angry Conversations With God you really should read—has observed that she is confounded by great poets (can you relate) since they use the same materials she does: words. About David’s book she says, “But where I’ve built a fort, he has erected a cathedral. Wheeler has revealed “the space behind our ribs” and I must remove my sandals.”

Space doesn’t permit me to cite a few of my favorites, but know that these are accessible, very interesting, fun, mysterious, and usually quite lovely. There is a sense of Christian spirituality here but they are not usually overt and certainly not sectarian. For what it is worth, Wheeler was mentored by a guy I love, Jim Schmotzer, one of the great leaders in campus ministry from The Inn (at Bellingham, WA) and he nicely thanks in his acknowledgments a batch of indie-owned bookstores (and indie singer-songwriter and H&M pal, Justin McRoberts, for those that like to connect the connections dots.) Wheeler’s a good guy, and his work indicates a maturity beyond his years. They could be read aloud on a variety of occasions, used as discussion starters in small groups or classes, or might inspire you in something like a daily quiet time. The poet writes that “My hope is that my poetry serves as a temporary testament to how grace has made right wha

t I have gotten wrong.” Not bad, believe me.

Cloud of Ink L.S. Klatt (University Press of Iowa) $17.00 You may recall how I raved and raved about the odd-ball work of this Calvin College literature professor, the wondrously playful words and syllables, the artistically rich array of poems found in his first prestigious volume, Interloper (winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry.) About half of those are so over-the-top creative that folks just love ’em for the sheer joy of messing around with what words can do. A few are very serious, one, in fact, somewhat about the death of my own father, killed in a tragic car wreck. That one, or so it seemed to me, was poetically rich but very evident.

Cloud of Ink L.S. Klatt (University Press of Iowa) $17.00 You may recall how I raved and raved about the odd-ball work of this Calvin College literature professor, the wondrously playful words and syllables, the artistically rich array of poems found in his first prestigious volume, Interloper (winner of the Juniper Prize for Poetry.) About half of those are so over-the-top creative that folks just love ’em for the sheer joy of messing around with what words can do. A few are very serious, one, in fact, somewhat about the death of my own father, killed in a tragic car wreck. That one, or so it seemed to me, was poetically rich but very evident.

This new work, pulled together after being awarded the 2010 Iowa Poetry Prize, earning the exceptional privilege of being published by this high-end poetry publishing legend, has some of the same edge as his first mind-boggling work. And, yet, this one feels a bit different. There is some greater clarity, some light, lots of truth, I’m sure of it.

Like Klatt’s previous one, there is a great little bit in the back, noting some of his allusions and inspiration, not unlike as in liner notes when a songwriter tells something about the meaning of a song. And what fun it is! For instance, Klatt notes, “Several of the titles in the book are modifications of lines from the journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson…” and offers hints such as “‘Aeronautics’ borrows a line from a letter of Herman Melville…” or “‘Darwin’s Mouth’ refigures a story from Charles Darwin’s autobiography…” and “‘Lines of Motion’ is suggested by Flannery O’Connor’s reflections on her own work in Mystery and Manners.” ‘For Lack of a Better World,’ Klatt tells us, is inspired by a painting of Joan Miro. You get the idea.

inspiration, not unlike as in liner notes when a songwriter tells something about the meaning of a song. And what fun it is! For instance, Klatt notes, “Several of the titles in the book are modifications of lines from the journals of Ralph Waldo Emerson…” and offers hints such as “‘Aeronautics’ borrows a line from a letter of Herman Melville…” or “‘Darwin’s Mouth’ refigures a story from Charles Darwin’s autobiography…” and “‘Lines of Motion’ is suggested by Flannery O’Connor’s reflections on her own work in Mystery and Manners.” ‘For Lack of a Better World,’ Klatt tells us, is inspired by a painting of Joan Miro. You get the idea.

Despite these fabulous clues, the reader has to be warned: we must puzzle out the meaning, entering in to how the poet sees the world, and it takes some work. Good art and slow reading is like that, of course, so I’m saying nothing new; just some hint that this is not the easiest sort of book to work on, but perhaps is less cryptic than the first.

Am I being critical? Not at all! Lew is beloved amongst his students, esteemed amongst his colleagues, and remembered by many as a great campus minister, back when he served with the CCO in Pittsburgh much more than a decade ago. (No wonder he has a few lines about Pittsburgh icons, steel-workers, and Heinz ketchup!) His poems have been published in some of the most classy lit journals around, and this is, I must underscore, serious stuff. One prominent reviewer, Kazim Ali, said they are nearly “un-quotable” which is the highest compliment—they are “so tightly joined…of languages variously plainspoken ad wildly swooping.” Ali continues, “Klatt’s seemingly spare and diffuse lyrics artfully assemble a complex and rich vision, generous in intention, provocative in enactment, ecstatic in spirit. A wild and welcome collection of poems from an exciting and dynamic thinker.” Yes, indeed, Dr. Klatt is rich… generous… provocative…ecstatic. I can vouch for that. You can hear two Christian leaders, more thoughtful and learned than I, discuss his book at the Books & Culture podcast, here. And, read this nice story from his college, including some good quotes about his work and some invaluable background. Enjoy.

I love these three very different books, Berry, Wheeler and Klatt. I hope you consider buying them, maybe sharing them with those would might appreciate them. Here are, for what it is worth, just a few more recently release poetry paperbacks we endorse.

Incarnality: The Collection Poems (with audio CD) Rod Jellema (Eerdmans) $28.00 This is a nice new collection of the works of one of the great Christian poets of our time, professor emeritus at University of Maryland, and a CD tipped in the back of him reading. There are ample selections from his four earlier volumes, and some new material. Barbara Brown Taylor wrote of a previous collection (A Slender Grace) “these poems find good news in the dark. Whether he sets us down in front of blind Willie Johnson playing the blues or asks us to spend a night on the bare floor of a church in Nicaragua, Rod Jellema teaches us to see what he sees—slender revelations flung toward us by the veiled but gracious God who means to lead us home.” This would make a spectacular gift for any poetry lover, any fan of Jellema, or for someone wanting to discover the joys of poetry anew. Very well done.

Incarnality: The Collection Poems (with audio CD) Rod Jellema (Eerdmans) $28.00 This is a nice new collection of the works of one of the great Christian poets of our time, professor emeritus at University of Maryland, and a CD tipped in the back of him reading. There are ample selections from his four earlier volumes, and some new material. Barbara Brown Taylor wrote of a previous collection (A Slender Grace) “these poems find good news in the dark. Whether he sets us down in front of blind Willie Johnson playing the blues or asks us to spend a night on the bare floor of a church in Nicaragua, Rod Jellema teaches us to see what he sees—slender revelations flung toward us by the veiled but gracious God who means to lead us home.” This would make a spectacular gift for any poetry lover, any fan of Jellema, or for someone wanting to discover the joys of poetry anew. Very well done.

Lovely, Raspberry Aaron Belz (Persea Books) $15.00 I suppose this may not be the ultimate compliment but it matters to some of us: this is published by a serious and mainstream general market publishing house, with a huge endorsements by a giant in the field of contemporary poetry. Belz is a thoughtful, Reformed evangelical, and is obviously taken seriously by the broader community of poets. John Ashbery says joyously of this new one, “reading it is like dreaming of a summer vacation and then taking it” although the stern picture of the author on the inside makes me wonder what kind of vacation that would be. Which is to say these are upbeat, lovely, approachable, but not cavalier or light-weight. Most of these were previously published in obscure and literary journals with hip and bohemian sounding names, only two of them I’ve even heard of: The New Pantagruel and The Washington Post. There ya go.

Lovely, Raspberry Aaron Belz (Persea Books) $15.00 I suppose this may not be the ultimate compliment but it matters to some of us: this is published by a serious and mainstream general market publishing house, with a huge endorsements by a giant in the field of contemporary poetry. Belz is a thoughtful, Reformed evangelical, and is obviously taken seriously by the broader community of poets. John Ashbery says joyously of this new one, “reading it is like dreaming of a summer vacation and then taking it” although the stern picture of the author on the inside makes me wonder what kind of vacation that would be. Which is to say these are upbeat, lovely, approachable, but not cavalier or light-weight. Most of these were previously published in obscure and literary journals with hip and bohemian sounding names, only two of them I’ve even heard of: The New Pantagruel and The Washington Post. There ya go.

Neruda’s Memoirs Maureen E. Doallas (T.S. Poetry Press) $15.00 This is another fine work published by this indie press edited by L.L. Barkat. This is not exactly about Pablo Neruda, nor is it a memoir. Much of this is about the perplexing beauty of nature, how the author grieved the loss of her brother, and a heart-filled, lyrical take on life which transcends the ordinary.

Neruda’s Memoirs Maureen E. Doallas (T.S. Poetry Press) $15.00 This is another fine work published by this indie press edited by L.L. Barkat. This is not exactly about Pablo Neruda, nor is it a memoir. Much of this is about the perplexing beauty of nature, how the author grieved the loss of her brother, and a heart-filled, lyrical take on life which transcends the ordinary.

The volume is meaningfully arranged around four main sections, entitled Enter, Listen, Exit, and Remember. A great collection by one whose work has been anthologized and well-reviewed.

Read her

at writingwithoutpaper.blogspot.

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

– any book mentioned –

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333

When I saw on FaceBook that “Contingency Plans” was mentioned, I clicked over to read the post, never thinking I’d find my own collection mentioned. What a lovely surprise this morning! Thank you.

I wish I could say I was the editor on ‘Neruda’s Memoirs.’ That honor, though, belongs to Marcus Goodyear, a fine poet in his own right. 🙂

Thanks so much for featuring these T. S. Poetry Press titles! 🙂

Great list of poets and poetry, Byron. William Carlos Williams has been a very important poet to me personally–as Wendell Berry has been. His mad farmer poems are some of my favorites. The idea of a book by Berry about WCW sounds like a great read!

Of course, I’m glad to see that you featured Wheeler and Maureen, and I’m equally excited to read up on the other poets you mentioned.

Thanks for doing what you do.