In writing about the death of Jesus as described in the gospel of Mark, Timothy Keller writes in  King’s Cross: The Story of the World in the Life of Jesus, of a officiating Roman centurion, who confesses that Jesus was the Son of God, a claim that Keller rightly calls “momentous.” Keller notes how few understood Jesus’ real identity; people had been asking and wondering. “But the first person to get it,” he says, “was the centurion who presided over his death.”

King’s Cross: The Story of the World in the Life of Jesus, of a officiating Roman centurion, who confesses that Jesus was the Son of God, a claim that Keller rightly calls “momentous.” Keller notes how few understood Jesus’ real identity; people had been asking and wondering. “But the first person to get it,” he says, “was the centurion who presided over his death.”

This was even more unlikely because he was a Roman. Every Roman coin of the time was inscribed “Tiberious Caesar, son of the divine Augustus.” The only person a loyal Roman would ever call “Son of God” was Caesar–but this man gave the title to Jesus. And he was a hard character. Centurions were not aristocrats who got military commissions; they were enlisted men who had risen through the ranks. So this man had seen death, and had inflicted it, to a degree that you and I can hardly imagine.

Here was a hardened, brutal man. Yet something had penetrated his spiritual darkness. He became the first person to confess the identity of Jesus Christ.

There is a striking contrast between the centurion and everyone else around the cross. The disciples–who had been taught by Jesus repeatedly and at length that this day would come—were completely confused and stymied. The religious leaders had looked at the very deepest wisdom of God and rejected it.

What penetrated the centurion’s darkness? How did he suddenly come into the light? For thirty years years I have been thinking about this question, trying to figure out why it was the centurion who first understood who Jesus was. Here’s what I believe shone the light into his darkness: The centurion heard Jesus’ cry, and saw how Jesus died.

In have only ever seen one person actually breathe his last breath. I’ll never forget that experience. Very likely you, too, have been present for a death only once or twice, if at all. But the centurion had seen many people die—and many of those by his own hand. Yet even for him this death was unique. He saw something about Jesus’ death that was unlike any other. The tenderness of Jesus, despite the terror, must have pierced right through his hardness. The beauty of Jesus in his death must have flooded darkness with light.

After a few good pages, Keller writes,

By saying the centurion “heard his cry” Mark is pressing the story right up to your ear. If you listen closely to that cry—my God, my God, why have you forsake me?—you can see the same beauty, the same tenderness. If you see Jesus losing the infinite love of his Father out of his infinite love for you it will melt your hardness. No matter who you are, it will open your eyes and shatter your darkness. You will at long last be able to turn away from all those other things that are dominating your life, addicting you, drawing you away from God. Jesus Christ’s darkness can dispel and destroy your own, so that in the place of hardness and darkness and death we have tenderness and light and life.

The New York pastor ends this moving chapter with a story of his own thyroid cancer, a fantastic excerpt from Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, and a reminder that it is true, after all.

Because of Jesus’ death, evil is a passing thing—a shadow [as Sam saw in Lord of the Rings.] There is light and high beauty forever beyond its reach because evil fell into the heart of Jesus. The only darkness that could have destroyed us forever fell into his heart. It didn’t matter what happened in my surgery—it was going to be all right. And it is going to be all right.

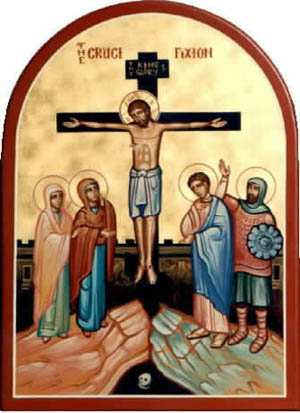

Note the shield on the character

on the right. The centurion, of course.

And the skull at Christ’s feet.

Death destroyed!