Any who are readers know of the experience when you just don’t want a book to be over. Either the characters are so interesting or the plot so compelling or the insight so helpful or the writing so utterly glorious that you just hate to turn that last page. Closing the book is bittersweet in those cases, sometimes painfully so. I know you know what I mean.

Any who are readers know of the experience when you just don’t want a book to be over. Either the characters are so interesting or the plot so compelling or the insight so helpful or the writing so utterly glorious that you just hate to turn that last page. Closing the book is bittersweet in those cases, sometimes painfully so. I know you know what I mean.

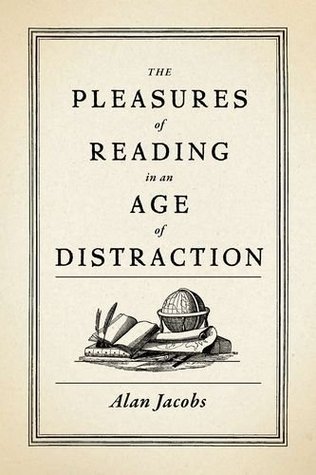

We here at the bookstore read books for a living although, like most people, we have to fight to make time for the books we really want to enjoy. As many titles as I skim and peruse, preview or study, it is still rather rare to utterly, exquisitely enjoy a book. It is a rare treat (even though there are many, many that I love and earnestly commend.) I finished two such books the other day. It was a bit sad on both counts, as I wanted more. A lot more. We are grateful for the authors, and I want to tell you about the two books that I am happy to say have been the best books of the year so far for me. One was a serious study of reading, the other a memoir. In this post I’ll describe the first one, The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction by Alan Jacobs and will return in a day or so to review the spectacular paperback, Jesus, My Father, the CIA: A Memoir, of Sorts…by Ian Cron.

For obvious reasons I am very interested in books about books and books about reading. Memoirs of readers and the books they’ve loved are a delight to me. Books about why reading is important—as foundational to our effort at imaging God as history-makers and culture-shapers—are helpful as I try to promote the development of the Christian mind. It is a good part of our story and what we are about here at the shop.

A few months ago I had the great opportunity to deliver some lectures (that ended up perhaps closer to sermons!) at Dallas Baptist University. My friend there, professor David Naugle, printed up buttons with the line of Augustine—tolle legge, “pick up and read” —as that was our theme for the weekend conference. As I have done other places, I listed reasons for reading, noting that reading is a required spiritual discipline, and reminding students that the God of the Bible has been revealed to us in words. Books matter. Books make a difference. They inform what we know and in some ways, how we know. Yada, yada, yada, literally.

But in all my exhortation–echoing the alarms about the erosion of habits of reading these days sounded by the excellent and very readable best-seller, The Shallows: What the Internet is Doing to Our Brain (out in paperback next week)–I perhaps underestimated one of the great reasons for reading: pleasure. My heart-felt call to take up the vocation of reading as Christians ended up a bit too much like scolding. I do not retract my conviction that we are nearly irresponsible in our day and age if we do not attempt to be well read but I might have tempered my tone if I had remembered delight.

Enter Alan Jacobs and his new book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction (Oxford University; $19.95) who eschews “must read” lists and the scolding approach of pharisees and elitists and the imperatives of the classic How to Read a Book (a book I often commend.) He disapproves of How To Read a Book? Why, the gentlemen Adler and Van Doren have been allies in our fight to get people to read more widely and carefully for decades— and Jacobs disapproves?

(Oxford University; $19.95) who eschews “must read” lists and the scolding approach of pharisees and elitists and the imperatives of the classic How to Read a Book (a book I often commend.) He disapproves of How To Read a Book? Why, the gentlemen Adler and Van Doren have been allies in our fight to get people to read more widely and carefully for decades— and Jacobs disapproves?

He does, he does. And what fun it is to learn why.

I do not have time and certainly not competency, to seriously review this splendid work. I hope you’ll trust me on this: this is a learned and interesting and informative book. Jacobs—who teaches literature at Wheaton College, for crying out loud, and has been considered one of the finest essayists working today (Wayfaring: Essays Pleasant and Unpleasant is his latest collection published by Eerdmans)—knows that the biggest draw, the biggest motivation, the biggest reason we should read in God’s good world is because it brings us pleasure. He wants to discover and re-learn the sorts of things that drew us to books in the first place. Can you remember such things?

There is much more to his argument than “reading is fun” and he takes us along as he heads sideways and backwards, here and there, covering much in his meandering reflections. He tells stories of students who have lost their previous love of reading, having their passion for books nearly stamped out of them by teachers and papers and grades. He tells of his own experience of the Kindle (a surprisingly wonderful thing for him) as he himself navigates the “shallows” and he ruminates on the time drawn away from books by blogging and his useful RSS feed. So he does speculate a bit about this “distracted” age and commends the practices of solitude and silence that allow us to most deeply engage with the printed page. But it is more than a jeremiad against “amusing ourselves to death” and I was delighted by it all. He has good stories of his own childhood reading and cites a few poignant biographies of readers, touching something within me as I read, wishing to have more of those kind of experiences with books.

Jacobs appreciates Carr and The Shallows and he also quotes the other book I was pushing a few months ago at Dallas, Proust & The Squid: The Story and Science of the Reading Brain by Maryanne Wolf. But he certainly is not opposed to on-line reading. He confesses to using the internet a whole lot, even to find quotes and obscure sources for this book (which is to say he’s not only not a Luddite but an honest man as well.) He studies medieval reports of reading (how “silent” reading developed) and he shares his opinions about how to generate greater enjoyment in that solitary world where we surround ourselves with a “cone of silence” and truly read, even in a buzzing coffee shop.

Do you want steps to take to be a better reader, a formula, a list, a how-to manual? You’re not going to find it here. Dr. Jacobs tells of the way many famous thinkers came to love books (Machiavelli famously dressed up, usually in costumes that matched the era or writers he was reading) and he is knowledgeable about the accumulated wisdom of how to be a better reader. He cites Auden, naturally, and Kipling, and writers as diverse as C.S. Lewis and the lead singer for LCD Soundsystem; he writes of Chesterton and Ivan Illich and Francis Spufford’s The Child That Books Built: A Life in Reading. This is a book-lovers delight and it offers nothing short of wisdom. But it doesn’t list steps or formulas.

section on the root meaning of the word serendipity is wonderful. Serendipity is a word we indie booksellers love because it plays into our approach to the craft of book display and sales: many people just happen upon books here at the shop that they just seem to think that they were meant to stumble upon; they, and we, believe that the right thing they most need at that time, by (providential) joyful serendipity, will find them. You see when one is reading in order to check off a list, grabbing what they are supposed to (whether wading through certain works because they are “classics” listed on some professors Important List or because of the hegemony of the market and the big box bestsellers that shout “everybody is reading it”) one often doesn’t follow Whim. Jacobs gets the phrase–reading by Whim–from a line by the poet Randall Jarrell who himself was astonished that some grand readers can re-read the same novel over and over. They do so, of course, because they love it so. Reading by whim–of course!

(And, yes, he needs to then ask questions about our desires, and what it is that we want to read. Is this like giving a child permission to eat only candy? Isn’t some broccoli good for you? Well obviously. But hear him out on that, too, which he explores quite nicely. He is a college professor, after all, and surely no slouch which will be very obvious. His other big book on this is called A Theology of Reading: The Hermeneutics of Love, published by the scholarly outfit Westview and sells for $34.00. Not too shallow, that one! )

I cannot explain all the truly good sections of the pleasurable Pleasures of Reading; it seems to cover so much ground so seamlessly and I was hardly distracted at all in the hours spent with it. It is one more wonderful example that nonfiction–and in some sections, quiet serious nonfiction—can be so enjoyable to read. Social science and a bit about the history of literary criticism, ruminations about the good and the true and the beautiful, can, indeed, be joyfully written, insightful and wise, and themselves quite beautiful. I think Jacobs is exemplary at this, drawing us in with almost sober, concise prose, telling light illustrations, offering a few dense footnotes and a bunch of funny ones (which you really mustn’t skip, if I can scold a bit—you’re gonna love ’em!) The heavy parts are supplemented with not a few witty lines— “Good Lord, No!” he cries, when he discovers the book How To Read Literature Like a Professor.

Or, read this passage, sweet and with a punch.

And there is something even more beautiful, perhaps, when we achieve this “eye-on-the-object look” not because we have found our vocation but because we have found our avocation—when the reason for our raptness is sheer and unmotivated delight. This is what makes “readers” as opposed to “people who read.” To be lost in a book is genuinely addictive: someone who has had it a few times wants it again, and wants it enough, perhaps, to beg a friend to hide the damned BlackBerry for a couple of hours, please.

The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction is a book I truly found pleasure in and, true to form, I learned a lot, was inspired by much, changed my mind about some things, agreed with most, and just didn’t want the book to stop. It was less than 175 pages, but it was substantial. And did I say it was fun?

Yes, fun. And important, too–a bonus. As one novelist wrote of it, it is “a gem of a book, filled with insight and wisdom, and the power to transform lives.”

Jay Parini, a renowned wordsmith himself, speaks of its appeal nicely,

As so many recent studies have suggested, the activity of reading itself is seriously threatened in this digital age. But Alan Jacobs — bless him — has an approach that will warm the hearts of serious readers and lead many prospective readers into the deeply satisfying swells of good prose. Reading should be a pleasure, and Jacobs shows us how to make sure we take delight in this work, which is not work at all. This is a witty and reader-friendly book, and it’s one I would happily give to any potential reader, young or old.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

any book mentioned above

2O% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

inquire here

if you have questions or need more informationHearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333

We are a not-for-profit educational organization, founded by Mortimer Adler and we have recently made an exciting discovery–three years after writing the wonderfully expanded third edition of How to Read a Book, Mortimer Adler and Charles Van Doren made a series of thirteen 14-minute videos–lively discussing the art of reading. The videos were produced by Encyclopaedia Britannica. For reasons unknown, sometime after their original publication, these videos were lost.

Three hours with Mortimer Adler on one DVD. A must for libraries and classroom teaching the art of reading.

I cannot exaggerate how instructive these programs are–we are so sure that you will agree, if you are not completely satisfied, we will refund your donation.

Please go here to see a clip and learn more:

http://www.thegreatideas.org/HowToReadABook.htm

ISBN: 978-1-61535-311-8

Thank you,

Max Weismann