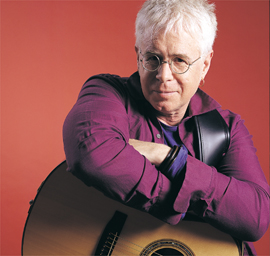

My friend Brian Walsh will be doing a presentation drawing on his recent book on the singer-songwriter, rock guitarist and road warrior Bruce Cockburn at the renowned Calvin College Festival of Faith and Writing this week. Later, Mr. Cockburn will be performing, preceded by an interview with Walsh. In honor of this remarkable bit of interaction and collaboration, and with a big hat tip to all involved at Calvin College, I offer this long rumination on the music of Bruce Cockburn, the writing of Brian Walsh, and this new book that explores how Cockburn’s work can inspire a more fruitful, faithful Christian imagination. It’s a great book and means a lot to me, as you will see.

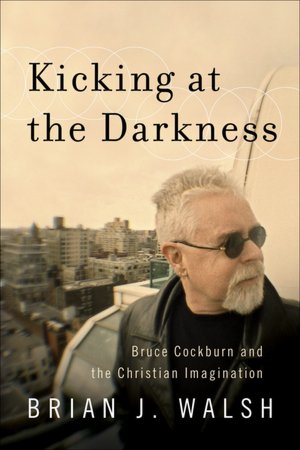

When Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian Imagination by Brian J. Walsh (Brazos; $18.99) hit the bookstore shelves in late fall I did a brief review, suggesting it was a book I adored, had read (in an early manuscript version) and that I would write about more thoroughly.

When Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian Imagination by Brian J. Walsh (Brazos; $18.99) hit the bookstore shelves in late fall I did a brief review, suggesting it was a book I adored, had read (in an early manuscript version) and that I would write about more thoroughly.

When we were doing our Hearts & Minds Best Books of 2011 announcements, we awarded it as one of the year’s best.

In fact, I said it was one of the year’s books that made me the happiest. I had hoped others might find that intriguing, and that BookNotes readers would order it. Some did, but others, I’m afraid, didn’t realize just how important this remarkable book really is. I’m not alone, though, in insisting that this is a book that is well worth your hard-earned coin. I smile in agreement when Brian McLaren says “I savored every page of this book.” And I agree with Marva Dawn’s enthusiastic assertion: “You need to read this book!”

Here is my heart-felt two part longer review of Kicking at the Darkness by Brian Walsh. The first essay is a rambling bit of my own story, why I found Cockburn so important decades ago, and how Walsh has been a writer whose Biblical insights about worldview and the prophetic imagination have influenced me greatly. Granted, my remarks are a bit impressionistic and, insofar as it is just a little bit of my little story, it may not be that interesting to you.

Still, I hope you give it a read—you may better understand why I write about many of the themes we pursue here, the sorts of books we commend, the authors we most appreciate. The confluence of evangelical faith, a reformational worldview, how Christian discipleship demands cultural engagement, our interest in the arts, and the really important influence of pop music form the backdrop as I tell about Bruce Cockburn. I’ve said for decades that Cockburn is in my top two or three all-time favorite recording artists, so I hope you’ll read my odd little overview.

Part Two is a bit more focused, describing the structure and themes of the book. In my first essay, actually, I end with three reasons why you should read Kicking at the Darkness. If this intrigues you, or you are willing to trust me, order it from us asap. If you want a bit more explanation of where Walsh goes with all this, read my summary in Part Two. I am (relatively) brief, there, and it is no substitute for taking in Walsh’s insight, good writing, powerful Bible lessons, and his seriously imaginative take on Cockburn’s seriously imaginative artistic vision. Enjoy.

CAUGHT TAKING A DIVE

Two songs taken together on the 1976 release In the Falling Dark, the title track and “Gavin’s Woodpile” nearly knocked me to my knees. Sure, In the Falling Dark had glorious praise songs (“Lord of the Starfields”, “Starfields”), sweet stuff about pregnancy (“Little Seahorse”) and a light little song with some prophetic edge insinuating that the cities of this world are somewhat like Babel (“Laughter”–ha, ha, ha) and the lovely view of heaven described as a “Festival of Friends.” But the slower “Woodpile” song is a hard, acoustic story about mercury poisoning and the “curse of these modern times.” I listened to it coupled with the vision of the whole creation groaning in “Falling Dark” which described the glory all around, and our ignorant lack of appropriate response. He sings that we are all caught “taking a dive.”

Woodpile” nearly knocked me to my knees. Sure, In the Falling Dark had glorious praise songs (“Lord of the Starfields”, “Starfields”), sweet stuff about pregnancy (“Little Seahorse”) and a light little song with some prophetic edge insinuating that the cities of this world are somewhat like Babel (“Laughter”–ha, ha, ha) and the lovely view of heaven described as a “Festival of Friends.” But the slower “Woodpile” song is a hard, acoustic story about mercury poisoning and the “curse of these modern times.” I listened to it coupled with the vision of the whole creation groaning in “Falling Dark” which described the glory all around, and our ignorant lack of appropriate response. He sings that we are all caught “taking a dive.”

That was a dumb expression a friend of mine used for when we did nonviolent direct action protests of prophetic civil disobedience (against nuclear weapons builders) and Cockburn’s use of it as I faced possible jail time just made me weep. Is that phrase “taking a dive” heroic, a summons to get arrested in protest, as we used the term? No. It is full of remorse, joining in brokenness, the brokenness of Romans 8, where the whole fouled up world is longing for redemption, if only we humans would get right with God. We are “caught” taking a dive, missing it all, blowing it, giving in and giving up. It is owning up to the sorrow of our situation–even the beasts cry “such a waste!” Years later–way out on the rim of the galaxy, as Cockburn put it then in a song of lament, where “the gifts of the Lord lie torn” —we realized Bruce was, as Bono put it, a ‘postmodern psalmist.’ He brought joy and tears together, like the Psalms.

Nobody has done this in our time like Bruce Cockburn and his music has been an influential soundtrack for Beth and I since our marriage in 1976, the year we discovered Cockburn. Allow me to tell you a bit about it.

***

It was the mid-70s, and I was listening daily to Jackson Browne, Neil Young, Dylan, The Band, early Elton John, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Dan Fogelberg, Roberta Flack, and the occasional prog rock or jazz record. And there was some of that new energy of punk. And a bit of soul and R&B. (Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, War.) Since the 60s I’d been moved by good tunes; pop music moved my feet just a bit but, more, it allowed my heart to be touched. My earlier girlfriends, my best guy friends, and my then new wife Beth all could attest that I’d talk about music til the wee hours if I could. From “Bridge Over Troubled Water” to the genius of the White album, from Harry Chapin to John Prine to Joan Baez to CSN to Gordon Lightfoot. My faith, my politics, and my whole worldview were shaped by John Lennon, James Taylor, and the wooly stuff from the Dead to the Allman Brothers. Bob Marley was young and interesting. I liked

early Elton John, Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, Dan Fogelberg, Roberta Flack, and the occasional prog rock or jazz record. And there was some of that new energy of punk. And a bit of soul and R&B. (Curtis Mayfield, Marvin Gaye, War.) Since the 60s I’d been moved by good tunes; pop music moved my feet just a bit but, more, it allowed my heart to be touched. My earlier girlfriends, my best guy friends, and my then new wife Beth all could attest that I’d talk about music til the wee hours if I could. From “Bridge Over Troubled Water” to the genius of the White album, from Harry Chapin to John Prine to Joan Baez to CSN to Gordon Lightfoot. My faith, my politics, and my whole worldview were shaped by John Lennon, James Taylor, and the wooly stuff from the Dead to the Allman Brothers. Bob Marley was young and interesting. I liked eccentric stuff like The Incredible String Band and It’s A Beautiful Day, the soul of Van Morrison, the lefty activism of Graham Nash. I heard Pete Seeger a time or two at anti-nuke protests and tried to listen to old Woody Guthrie. I would eventually be an early fan of a young band from Dublin, who fused passion and politics and prayer, but that would be years later, long before the brilliance of Arcade Fire or Radiohead.

eccentric stuff like The Incredible String Band and It’s A Beautiful Day, the soul of Van Morrison, the lefty activism of Graham Nash. I heard Pete Seeger a time or two at anti-nuke protests and tried to listen to old Woody Guthrie. I would eventually be an early fan of a young band from Dublin, who fused passion and politics and prayer, but that would be years later, long before the brilliance of Arcade Fire or Radiohead.

Few of the contemporary Christian music pioneers

that that I listened to in the late 70s ever fully captured my heart. Larry Norman, Randy Stonehill and early Talbot brothers stood out, beside our friend James Ward, but if secular pop groups sang mostly about lost love and romance, why did CCM singers only sing about faith and worship? Why no Christian songs about justice, about ecology, about friendship, about travel, about sex, about loneliness, about race relations? I don’t know which was more frustrating, songs with no reference to God or songs about God with no reference to real life.

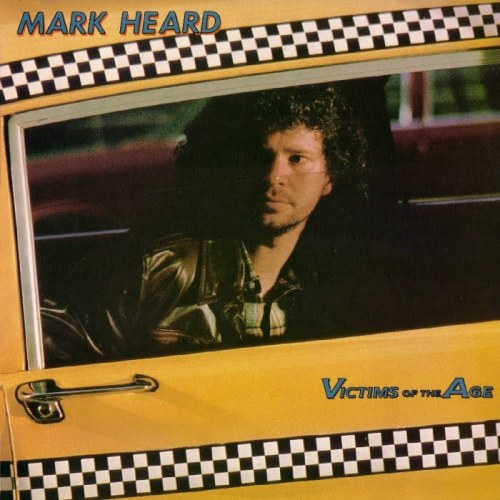

(This did begin to change, in part due to great songwriters like Mark Heard and Mike Roe and Glen Kaiser, for instance. And, eventually, the spectacular work of Bill Mallonee and VOL, which is a whole other story.) It would take years before CCM stars wrote anything about the needs of the poor, and even then there was nary a song about injustice or the causes of poverty. Much has been written about the insular tone and limited vision of the evangelical awakening in the last quarter of the 20th century and our bookstore—carrying books on science and film and business and global injustice and such has attempted to witness against the sacred-secular dualism that was both the downfall of, and reinforced by, the evangelical CCM industry.)

Kaiser, for instance. And, eventually, the spectacular work of Bill Mallonee and VOL, which is a whole other story.) It would take years before CCM stars wrote anything about the needs of the poor, and even then there was nary a song about injustice or the causes of poverty. Much has been written about the insular tone and limited vision of the evangelical awakening in the last quarter of the 20th century and our bookstore—carrying books on science and film and business and global injustice and such has attempted to witness against the sacred-secular dualism that was both the downfall of, and reinforced by, the evangelical CCM industry.)

This ground has been well covered (Charlie Peacock’s book At the Crossroads, now out of print, is very important and a great read) and I don’t recall it to bash the Jesus movement years or the talented recording artists that we enjoyed in those years, such as Keith Green, Phil Keaggy, or Amy Grant who, despite being an icon of the 80s and 90s CCM sub-culture was, in fact, a bit out of the box and a very fine lyricist. But it does frame some of the context for Cockburn’s early appeal for many of us. Fast forward several decades or so and other kids stuck in the CCM world found similar weaknesses, and their memoirs are wonderful to read for those of us who follow that sub-culture. See, for instance, Sects, Love, and Rock and Roll: My Life on Record by Joel Henge Hartse (Wipf & Stock; $23.00. Or, get the tremendously written report by Spin writer, Body Piercing Saved My Life: Inside the Phenomenon of Christian Rock by Andrew Beaujon (Da Capo; $16.95)

I remind you of the less than full-orbed (and often less than artistically mature) CCM music of those years–and my fierce devotion to more substantial artists like Jackson Browne—so that you might get just a hint of the absolute thrill, the deep joy, the jaw-dropping, too-good-to-believe discovery of one Bruce Cockburn, an exceptionally literate Canadian folkie (he  knew Neil Young from up in Alberta, somebody said) turned bluesy rocker. Even then, after only a few hippy-folk albums under his belt, he was considered one of the great guitarists around. It was being circulated at the time that evangelical rocker Phil Keaggy was considered—by Jimi Hendrix, at least—to be the world’s best electric guitar player. Keaggy was later quoted as saying that he couldn’t hold a candle to Cockburn. A drop-out of Berklee School of Music where he studied jazz, Cockburn could do extraordinary finger picking, could find new chords and tunings that made the guitar gods gently weep, and could barrel house with blues like nobodies business.

knew Neil Young from up in Alberta, somebody said) turned bluesy rocker. Even then, after only a few hippy-folk albums under his belt, he was considered one of the great guitarists around. It was being circulated at the time that evangelical rocker Phil Keaggy was considered—by Jimi Hendrix, at least—to be the world’s best electric guitar player. Keaggy was later quoted as saying that he couldn’t hold a candle to Cockburn. A drop-out of Berklee School of Music where he studied jazz, Cockburn could do extraordinary finger picking, could find new chords and tunings that made the guitar gods gently weep, and could barrel house with blues like nobodies business.

And then he started singing about Jesus.

Excuse me while I collect myself. The lump in my throat as I write that has led to tears in my eyes, as I consider the goodness of God to touch the lives of artists who can so touch our lives. For evangelical Christians like myself who believe there is simply nothing more important than a proper understanding of the Christ-exalting life of Kingdom discipleship, finding that Cockburn had become a Christian was only matched by the night my best friend Ken Heffner and I listened with grins and tears and high-fives and praises to God to the soul-stirring Slow Train Coming that testified to Mr. Dylan’s undeniable conversion to Yeshua. I will never forget that night, and I will never forget the first Cockburn album I ever heard, bought from a budget bin at a Pittsburgh record shop.

Which brings me to this: if you care about thoughtful pop music that is clearly the work of an artist on a spiritual journey, a great singer-songwriter, who has earned Juno after Juno (the Canadian music industry’s equivalent to a Grammy) who is esteemed by some of the finest contemporary musicians on the planet—U2, for instance, The Band, Jackson Browne, T-Bone Burnett, Barenaked Ladies, Buddy Miller, Joe Henry, Eric Clapton–you owe it to yourself to listen to Bruce Cockburn. His earliest stuff is impressive, mostly acoustic, although even his later louder records–the middle, political period, when he started doing artsy spoken word stuff, too—include gentle  ballads. He has worked with jazz violinists, wild trumpeters, gospel singers like The Blind Boys of Alabama, politico folk-singer Ani DiFranco, and slide guitar master Bonnie Raitt. He has released hot live albums with raging bands and, a year or so ago, Slice of Life, which is a double live album of his solo performances. Anything, Anytime, Anywhere is a compilation of single hits he had out, from 1979-2002. Here is a complete discography, and it is fun to see his expansive career, the interesting titles and the often obscure artwork on the jackets. (Don’t forget to come back here, though!)

ballads. He has worked with jazz violinists, wild trumpeters, gospel singers like The Blind Boys of Alabama, politico folk-singer Ani DiFranco, and slide guitar master Bonnie Raitt. He has released hot live albums with raging bands and, a year or so ago, Slice of Life, which is a double live album of his solo performances. Anything, Anytime, Anywhere is a compilation of single hits he had out, from 1979-2002. Here is a complete discography, and it is fun to see his expansive career, the interesting titles and the often obscure artwork on the jackets. (Don’t forget to come back here, though!)

Cockburn’s producer of recent years, Colin Linden, himself stood-in with The Band, traveling with that legendary group for a while. His slide guitar and rootsy Hammond B3 can be raucous or soulful, and has served Cockburn wonderfully. Over the course of Cockburn’s career there have been some truly sweet songs, some avante garde extended jams, some blazing electric guitar solos (his prophetic, vulgar cry against the vulgarities of the injustices of the International Monetary Fund, “They Call It Democracy” comes to mind, especially from the live recording) and some exceptionally sweet slide guitar (“The Whole Night Sky” features some heart-wrenching playing by Bonnie Raitt as well and is one of my favorites, as he sings gorgeously about shedding tears.)

A few albums were nearly travelogues, offering poetic impressions drawn from his journeys in Nepal, publicizing land-mines in Mozambique, playing with local musicians as he researched desertification in Mali, liberation-theology anthems written in Central America, alongside journalistic songs about dusty roads and village chickens while staying with refugees in Guatemala. “Dust and diesel, rises like incense from the road” he sings in a truly wonderful travelogue as he rumbles through rural Nicaragua. An older song artfully describes watching an old lady sleeping on a Japanese train—“head bobbing almost imperceptively”—and a concert favorite powerfully describes riding a bike through “the Tibetan side of town.” Indeed, a 2004 albu

a bike through “the Tibetan side of town.” Indeed, a 2004 albu

m captured his global citizenship and world travels with the title Breakfast in New Orleans, Dinner in Timbuktu.

Yes, Bruce continued to sing about Jesus, with Biblical images and spiritual themes—often mixed with songs about erotic desire, or about political injustice. We first started carrying the author Brennan Manning before he was very popular because Cockburn cited his “Shipwrecked at the Stable Door” chapter from a Manning book which was then entitled Lamb & Lion (but is now out as The Relentless Tenderness of Jesus) in a song Cockburn wrote with that title. If Cockburn was reading this guy, we wanted in on it, and we soon became Brennan fans, too. But he was never preachy like most CCM rockers and was never embedded in a fundamentalist subculture. In fact, some of the most indicting words against the Christian right come from Cockburn, in songs like “Gospel of Bondage” from his 1988 album—a powerful favorite—called Big Circumstance.

An active humanitarian, it is ironic that one of Cockburn’s most well-known songs is “If I Had a Rocket Launcher” (from Stealing Fire) which channeled his rage against US-backed helicopters spraying bullets on refugee children in counter-insurgency warfare in the mid-80s. It is a passionate song, with the understandable line, after singing about the horror he had witnessed “If I had a rocket launcher, some son-of-a-bitch would die.” It is a song he used to apologize for, that he told me once he didn’t fully affirm—it is the artists job to report authentic feelings, he said, and, like it or not, this is how he felt as he witnessed for peace. Even pacifists, maybe especially pacifists, sometimes cry out in rage, and Cockburn gave voice to the feelings many of us felt as we worked in the 80s and 90s to stop US-backed injustice in places like Central America and South Africa. “Rocket Launcher” and “They Call It Democracy”, “Where the Death Squad Lives” and the drum-based chant about First Nation’s people’s land rights, “Stolen Land” are quite different than the C.S. Lewis-inspired images of “Wondering Where the Lions Are” which he sang on SNL in 1980, yet there was a serious social vision in his earliest albums, and there have been upbeat and pleasant tunes even in his most politically-charged releases.

I recall visiting new friends at the Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto in what must have been 1980. Cockburn had moved to the rough and tumble city–the following year he’d be seen on a gritty album cover smoking in an urban café, on a release called Inner City Front—and his brand new album was said to be influenced by reggae, by the sounds of his experiences in the city, by some hard times in his life. It was called Humans and hearing the needle drop in Toronto, near Younge Street, meant the world to me. To this day, this album—with “Rumors of Glory” and “What I Did on My Fall Vacation” and “Grim Travelers in Dawn Skies” (“little boys and girls from the Red Army underground, they’d blow away Karl Marx if he had the nerve to come around”)—is still one of my favorite records of all time. With clever lines about “fascist architecture” and Bergman films and allusions to T.S. Elliott; there were harsh lines like “gray-suited businessmen pissing against the wall” and the slo-mo horror of watching a car crash in Tokyo, and I knew I was in deep. This is incarnational stuff, the Word turned flesh, some heavy mix of poetry and passion, gospel and culture, clarity and distortion that I simply had never encountered before.

Dawn Skies” (“little boys and girls from the Red Army underground, they’d blow away Karl Marx if he had the nerve to come around”)—is still one of my favorite records of all time. With clever lines about “fascist architecture” and Bergman films and allusions to T.S. Elliott; there were harsh lines like “gray-suited businessmen pissing against the wall” and the slo-mo horror of watching a car crash in Tokyo, and I knew I was in deep. This is incarnational stuff, the Word turned flesh, some heavy mix of poetry and passion, gospel and culture, clarity and distortion that I simply had never encountered before.

Cockburn’s lament over a broken marriage (“What About the Bond?”) which cries out “What about the bond/ sealed in the loving presence of the Father?” was the first song I ever heard about Christian divorce, perhaps still the only one I know of that doesn’t bog down in cheap sentiment. As I wrote earlier, Cockburn was refreshing as a poet and singer because he was filled with faith, even hope, but was gritty and real, tragic, even. He blamed himself for many of his troubles, deeply and importantly, in a great tune called “Fascist Architecture.” Cockburn stands almost in a class by himself, writing smart songs like this, stuff even the Talking Heads couldn’t imagine in those years. His insight and lyrical style could hold up against the best singer-songwriters of the day. And yes, God was in all of this. Rumors of Glory, indeed.

One simple example: in the travelogue song “How I Spent My Fall Vacation”, the first line is “Sun went down, looking like the eye of God” and after all manner of adventure and ponderous thoughts—“will I end up like Bernie in his dream/displaced person in some foreign border town?”) and the last line is “while the eye of God blazes at us like the sun.” The slight reversal in imagery so struck me and I’m still taken by its cleverness, and how it frames our comings and goings. One of the leaders of the famous Greenbelt festival told me recently that Cockburn’s first line of his first song was that, and it won him over instantly. Amen!

Over the next decades, Cockburn would continue to bless us with artful tellings of amazing grace amidst ambiguity and pain, doubt and searching, alienation and struggle, horror and good humor. He would testify about “grass growing up through cement” and invite us to find the risen Christ in “this prison camp world.” He would do an acoustic Christmas album that included some stunning songs, played provocatively in a minor key, before current hipsters learned to capture the angst of Advent. He would whistle, he would moan, he would protest, he would move back to the country (doing a few lovely country-tinged albums with producer T-Bone Burnett, Nothing But a Burning Light and Dart to the Heart), take up serious biking, tour endlessly, would do an album of delightful instrumentals. He would re-work crowd pleasers like “Wondering Where the Lions Are” with scat singing in falsetto, rework his earliest “Jesusy” songs even as he’d often sound like a mystic Unitarian. He would play a resonator guitar, raise up the plight of native peoples, and sing about sex and pleasure in ways that pointed us to the Divine moment in it all, all while reporting from various humanitarian projects he was involved with, sometimes through Canadian relief agencies. There are only a few artists whose life-time of work I continue to follow, and who continue to challenge and impress and delight. Cockburn is at the top of the list.

Over the next decades, Cockburn would continue to bless us with artful tellings of amazing grace amidst ambiguity and pain, doubt and searching, alienation and struggle, horror and good humor. He would testify about “grass growing up through cement” and invite us to find the risen Christ in “this prison camp world.” He would do an acoustic Christmas album that included some stunning songs, played provocatively in a minor key, before current hipsters learned to capture the angst of Advent. He would whistle, he would moan, he would protest, he would move back to the country (doing a few lovely country-tinged albums with producer T-Bone Burnett, Nothing But a Burning Light and Dart to the Heart), take up serious biking, tour endlessly, would do an album of delightful instrumentals. He would re-work crowd pleasers like “Wondering Where the Lions Are” with scat singing in falsetto, rework his earliest “Jesusy” songs even as he’d often sound like a mystic Unitarian. He would play a resonator guitar, raise up the plight of native peoples, and sing about sex and pleasure in ways that pointed us to the Divine moment in it all, all while reporting from various humanitarian projects he was involved with, sometimes through Canadian relief agencies. There are only a few artists whose life-time of work I continue to follow, and who continue to challenge and impress and delight. Cockburn is at the top of the list.

I wish I could describe the sonic complexity and diversity of his 30 some recordings, but words fail. His lyrics usually match his passionate playing, and his musicianship continues to be entertaining, if sometimes demanding. (From his earliest work he has shown serious jazz influences, sometimes world-beat tinges, and in Small Source of Comfort, his most recent, some neo-classical overtones, even using a string section for the first time ever.) I think this newest one may be my least favorite since his first few folkie ones, but even a mediocre Cockburn album, with a few misses, is better then most.

fail. His lyrics usually match his passionate playing, and his musicianship continues to be entertaining, if sometimes demanding. (From his earliest work he has shown serious jazz influences, sometimes world-beat tinges, and in Small Source of Comfort, his most recent, some neo-classical overtones, even using a string section for the first time ever.) I think this newest one may be my least favorite since his first few folkie ones, but even a mediocre Cockburn album, with a few misses, is better then most.

Cockburn’s broad Christian worldview remains evident, although it seems that his faith is less evangelical than it once was, not that it was ever very

traditionally pious. In the new century, he continued to push us to think about global affairs and the direction of our pubic life, about faithful responses to the beauty and the sorrow and the complexities of the human condition, perhaps unmatched in all of rock music. He railed against the destruction of the rain forest, laughed at death–he has a morbid sense of humor— named his fears, celebrated his hope, such as it was. One album, with a gruesome song or two, (and a few beautiful ones) is called, tellingly, You’ve Never Seen Everything.

Cockburn does relish the unusual, so it doesn’t surprise that he sings about seeing a pile of skulls in a memorial to the killing fields in Cambodia. But he is also a funny chap and for a while closed his concerts with the “Look on the Bright Side of Life” from the satirical crucifixion scene from the goofy Life of Brian. Or then, again, the one about his own death, an upbeat rocker “Tie Me At the Crossroads” which I always enjoyed. Morbid, maybe, but he never seems depressed, even though his lyrics reflect an honest appraisal, even if tongue is in cheek.

Cockburn helped me think about the cold war–we laughed with him as he describes a guy in his “commie fur hat” and took comfort when such a politically experienced thinker could still sing songs of hope and joy. (“Joy Will Find a Way” was an early song on an album by that name.) Indeed, the lovely “Wondering Where the Lions Are” is, in fact, a song about the horrific “lions” of nuclear weapons; “Sun’s up, looks okay, the world survives into another day” literally kept me from growing too cynical in my years working against nuclear weapons and our evil willingness to commit mass murder with them.

I do not think it is fair to say Cockburn was trendy, but he has helped

us enter into the issues of the day, often with prescience. He would

sing about the destruction of the rainforest (“inject a billion burgers

worth of beef”), Eastern bloc dreariness; create tunes that captured the

spookiness of places of great sorrow (like the killing fields of

Cambodia) and helped us see the beauty of nature. (“Lord of the

Starfields” was a song of praise on 1976 In The Falling Dark, a

song whose poetry still strikes me as deeply worshipful and yet

wonderfully suited to a pop song.) “Silver Wheels” from that same early

album narrated a road trip noticing and worrying about the advertising

that bombards our field of vision which is more relevant now than ever.

Years later, though, he’d remind us that we could see the mystery of

the divine, even in a junkyard. And did I mention he is still disgusted

with the Christian right? He was and he is. (Yet, when the situation

calls for it, he responds with decency and even patriotism, as in “Each

One Lost” a poignant song on the most recent album (Small Source of Comfort) about witnessing a flag ceremony in Afghanistan where the bodies of two dead soldiers were being brought across the tarmac.)

In the years after our own radioactive mess and political irresponsibility here in central Pennsylvania at the Three Mile Island reactor, Bruce helped us lament the horrible nuke disaster in Chernobyl. His bluesy cry about the Soviet style cover-up there, “Radium Rain” (from Big Circumstance) includes one of the longest guitar solos in the expansive Cockburn catalog. I have said before how moved I was hearing Brian Walsh read Colossians 1 with that searing musicianship in the background, at CCOs Jubilee conference one year, and how it remains for me to this day one of the most memorable liturgical experiences of my life.

BRIAN J. WALSH

Brian Walsh reading the Bible perfectly timed over Bruce Cockburn’s guitar solo, relating Old Testament prophecies to Cockburn’s assessment of 20th century energy policy and technological illusions? For those who know Walsh’s remarkable work this is no surprise. Walsh has himself given us a body of work, books about a Christian worldview such as The Transforming Vision: Shaping a Christian Worldview (IVP; $16.00) or how that worldview might fruitfully engage postmodern thought and culture in the excellent Truth Is Stranger  Than It Used to Be: Biblical Faith in a Postmodern Age, (IVP; $22.00) (both co-authored by J. Richard Middleton) or how a serious postmodern study of a Biblical book like Colossians might help us change the world (Colossians Remixed: Subverting the Empire, co-authored with his wife, Sylvia Keesmaat, a New Testament scholar of considerable renown, published by IVP; $23.00.) His work co-authored with Stephen Bouma-Prediger, a deep study of our “culture of displacement” (Beyond Homelessness Eerdmans; $27.00), is demanding but one of the more profound examples of Christian scholarly cultural criticism written in recent decades. What an audacious book, naming so much of the malaise and dysfunction of our time. I’ve reviewed each of these before and commend them all for your serious study and edification.

Than It Used to Be: Biblical Faith in a Postmodern Age, (IVP; $22.00) (both co-authored by J. Richard Middleton) or how a serious postmodern study of a Biblical book like Colossians might help us change the world (Colossians Remixed: Subverting the Empire, co-authored with his wife, Sylvia Keesmaat, a New Testament scholar of considerable renown, published by IVP; $23.00.) His work co-authored with Stephen Bouma-Prediger, a deep study of our “culture of displacement” (Beyond Homelessness Eerdmans; $27.00), is demanding but one of the more profound examples of Christian scholarly cultural criticism written in recent decades. What an audacious book, naming so much of the malaise and dysfunction of our time. I’ve reviewed each of these before and commend them all for your serious study and edification.

If you’ve read any of these books you already know that Walsh is a serious Cockburn fan. He has long been a student of Cockburn’s work, paying particular attention to his allusive lyrics, using his lyrics to help unlock insights from the Bible (and using the Bible to help us appreciate some of Cockburn’s not-so-hidden meanings.) Walsh hasn’t written a book where he hasn’t quoted Cockburn and he has even taught college courses on the “prophetic imagination” of the radical, Christian poet.

Walsh is a serious Cockburn fan. He has long been a student of Cockburn’s work, paying particular attention to his allusive lyrics, using his lyrics to help unlock insights from the Bible (and using the Bible to help us appreciate some of Cockburn’s not-so-hidden meanings.) Walsh hasn’t written a book where he hasn’t quoted Cockburn and he has even taught college courses on the “prophetic imagination” of the radical, Christian poet.

I have appreciated this about Walsh (I’m a devout Cockburn fan, after all) and, I must say, it has helped me enjoy Cockburn’s music that much more. Sure, when I was in high school and college I’d ramble on about all kinds of theories about all kinds of music. (Was Paul dead? Was Jackson Browne sending out coded messages about the gospel? What did Dylan mean by that? Why did the Doobie’s sing about Jesus? Why were there gospel singers in that song “The Weight” and why did Van quote all those romantic British poets? What’s with Paul Simon’s references to Jesus? Heck I even researched in sophomoric fashion the mystical incantations of Tales of Topographic Oceans by Yes. ) But Walsh doesn’t speculate like an immature, curious fan, he engages Cockburn’s lyrics with serious insight, offering helpful music criticism, rich, intellectually credible and fruitful. A good critic can help us understand and appreciate the imaginative vision of an artist, and Walsh has done so, helping us both understand and more greatly enjoy the artistry of Bruce Cockburn, postmodern psalmist.

THE BOOK And, now, he has done so in a whole big book, Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian Imagination (Brazos Press; $18.99.) I had the great privilege of helping read through some of it and cannot believe that I have an endorsing blurb on the back (next to wonderful recommendations by Brian McLaren, who has quoted Cockburn a time or two himself) and New Testament scholar Richard Hays. I already noted that there is a great endorsement by Marva Dawn who I once teased about not really liking rock ‘n roll which I now publicly take back. As a bit of a blurb-meister, this is one of my proudest moments,

And, now, he has done so in a whole big book, Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian Imagination (Brazos Press; $18.99.) I had the great privilege of helping read through some of it and cannot believe that I have an endorsing blurb on the back (next to wonderful recommendations by Brian McLaren, who has quoted Cockburn a time or two himself) and New Testament scholar Richard Hays. I already noted that there is a great endorsement by Marva Dawn who I once teased about not really liking rock ‘n roll which I now publicly take back. As a bit of a blurb-meister, this is one of my proudest moments,

Here is what I most sincerely said:

I’ve been listening to Cockburn for more than three decades and reading Walsh for almost that long, and I can hardly imagine surviving these times, let alone believing that joy will find a way, without the artistry and insight of both. This is an extraordinarily ambitious project, years in the making, and there is profound insight on every page. I recommend it with great enthusiasm and immense gratitude.

One does not have to like every Cockburn song or album, let alone agree with every view he seems to express, to appreciate his exceptional gift as songwriter and musician and to be aided by his observations, rendered in song. And one need not agree with every line in every Brian Walsh book to appreciate his preacherly gospel call to be faithful to the Biblical narrative, and to reject worldly accommodation to the idols of modernity.

In other words, whether you love Cockburn and/or Brian Walsh or not, this book is profitable, interesting, important, and I commend it to you.

Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian Imagination is a very good book. You should read it. Here are three reasons why.

THREE REASONS TO READ THIS BOOK

1. Firstly, it is, indeed, a great introduction to the thought and insight of one of the great artists of our time. If you care at all about pop music or contemporary poetry, you should know Cockburn. You may not want to immerse yourself in his huge body of music, but reading this book (hopefully with some of his tunes playing in the background) is a good way to explore his world, to be touched by his lyrics, to be challenged by his take on life and times. I’m a fan of reading about authors and their work—I routinely recommend books about Wendell Berry or Abraham Kuyper or Martin Luther King (not just their primary sources, which, obviously should be read as well) and am happy to say that reading about them can help you understand and thereby more richly appreciate their real work. So reading Kicking at the Darkness is perhaps the best way to come to value Cockburn’s work, learning about it and plumbing its meaning and framing it as it ought to be framed. Cockburn himself, by the way, has met with Brian a time or two, and has maybe been bemused by Walsh’s theologically readings of his music. I’ve heard Cockburn talk about his song writing at the Calvin Festival of Faith and Writing several years ago where he seemed exceptionally humble about and, yes a bit bemused by, the serious attention some of us give to his work. Yet, in a personal email to Brian after reading the manuscript, Bruce exclaimed how very good it was to be so wonderfully unde

rstood. Cheers!

There is no resource like this that attends to the substance of Cockburn’s work, and it is a great way to learn about an esteemed contemporary artist.

2. Secondly, this is a good way to more deeply understand the Bible itself. Walsh is, if anything, a Bible reader, a Bible scholar, a Bible teacher— I happen to know how worn his own Bible is, how well used it is — you wouldn’t believe the scribbles and notes and fingerprints and pages falling out. If this interaction with a modern poet and the ancient prophetic text illumines the poet, that is great, but if it illuminates God’s own Word, that is even better. And I think it does: to hear the Biblical text through the ears of Walsh listening to the songs of Cockburn, pulls out insights, applies new wisdom, underscores certain verses, that we just might not get otherwise. I agree with an old song by Cockburn, “Maybe the Poet” (about Ginsberg somebody speculated, or maybe about Ernesto Cardenel?) which shouts “you need him and you know it.” Yep, listening in on the conversation—Cockburn’s lyrics lined up with Isaiah and Jeremiah and James and Jesus and Paul—well, the Bible comes alive! And it comes alive in contemporary power, not sentimentally, but with grit and guts. Kicking at the Darkness is not exactly a Bible study (like the Walsh/Keesmaat Colossians book, or the creative Biblical monologues in Beyond Homelessness) but it comes close. You simply don’t read Walsh, or talk to Walsh, without the Bible coming into things. Read this book about pop music and learn the Word. I dare you.

3. This may not at first seem important to many folks, maybe not even all BookNotes readers, but I cannot overstate just how important this truly is: reading Walsh’s examination of, engagement with, living into, the vision of Bruce Cockburn is a great (great!) example of wise and fruitful literary criticism. We all are bombarded daily with texts, with images, with sounds and sights. How do we see? How to make sense of it all? Take in and discern and apply? How do we interpret? Whether it is a video game or a literary novel or The Hunger Games blockbusters, Seinfeld re-runs or the latest indie rock show, a TV preacher or a BookNotes book review, what will you make of it? How have you learned to evaluate and discern wisely?

Walsh is curious, and a rare reviewer: he is generously critical, happy and heavy, open and discerning. That is, he doesn’t just dismiss insight and truth that comes from unlikely sources (he is famous for using pop culture, movies and music in his sermons and campus ministry at the University of Toronto) so he starts with a hermeneutic of generous hope. But he’s no fool and he does not suffer fools too gladly, either; that is, he discerns well the zeitgeist, the spirit of the age, the deeper idols that shape and deform even the best stories. So while he is open to truly hear and be touched by all manner of things, he holds up all things, as 1 John 4 instructs, to the discerning eye of the faithful Biblical test. I’d like to say he models and shows us how to be “in the world but not of it.” You could say he has a pretty active “crap detector” as Hemingway (according to Neil Postman, at least) once called it.

So, to say it again: first, you need to read this book because it will introduce you to an important musician and critical acclaimed lyricist who happens to be a Biblically-literate thinker. Secondly, Walsh uses Cockburn’s religious faith and imagery to do extraordinary Bible study, so you will not only learn about Cockburn, you will learn something new about the Bible, and the God who stands behind it. What a good gift this book is, helping the Word get cracked open before us.

And, thirdly, you will learn how to be engaged and thoughtful about the body of work of a serious artist, how to take even odd lines and perplexing metaphors and see how they might point us to redemptive insights about the meaning of our lives under the sun. We all need help learning to discern the voices and ideologies around us, and following the careful explorations of Walsh on Cockburn as they both try to understand the modern world is a good exercise in cultural exegesis. You will be wiser for it as the book models a helpful, important practice.

Walsh has given us in Kicking at the Darkness a supreme example of a thoughtful Christian reading of what for some will be controversial texts (songs about left wing revolutionaries, about sex, about rejection of churchy dogma, about greed and injustice, about death and fear and love.) Rather than avoiding these heavy topics, Walsh helps us be open, to have our own hearts opened in order to see the good in the art. He realizes that the offering of artists must be firstly considered as art. His creative appraisal and appropriation of the art of Bruce Cockburn is a great example of how to help us flourish–for the glory of God and the common good.

You see, I belabor this for you, our friends and customers, because I think we all need to know how to do this—this art of interpretation, this way of nurturing the gift of cultural discernment— so, even if rock music isn’t your thing, and the wild and wooly worlds of Cockburn and Walsh aren’t your own, even if these songs aren’t that appealing to you, I’d still invite you to consider it. Spending a few weeks pondering this uniquely reformational Christian take on an important and acclaimed recording and performing artist of our time can only help deepen and mature your own practices of cultural engagement. Perhaps you will disagree with Walsh’s interpretations and how he appropriates Cockburn’s take on life. (For the record, I agree with almost all of Brian’s insights; I think maybe there was one interpretation which I thought was over-reaching.) Perhaps you will disapprove of his use of the Bible in his project of “seeing” Cockburn Christianly. That’s okay. As Bruce says, and as Brian quotes approvingly in the introduction, we are all “stumblers.” We have reason to agree with Cockburn’s reminder that “love rules” so there is freedom and grace. Right?

Freedom and grace, politics and poetry, rock and roll. Bruce Cockburn means the world to me and if you’ve wondered—as I’m told some people do—how in the world we ended up creating a Christian bookstore like Hearts & Minds, such as it is, you should know that much of it got dreamed up to a Bruce Cockburn soundtrack. Indeed, there were a few key moments in my life, some risks I took, some faithful steps I tried to pursue, that ended up shaping the man I’ve become, that may not have occurred where it not for how Cockburn pointed me to “the glittering joker dancing in the dragon’s jaw.” There have been decisive moments for me with Bruce’s music (and even a bit of correspondence) that helped Beth and I and our closest friends as we took up the vocation of social change and cultural renewal and Christian hope in history—as Bruce put it, “waiting for a miracle.”

KICK AT THE DARKNESS TIL IT BLEEDS DAYLIGHT

It may be popularized because Bono cited it (in his song “God Part 2” on Rattle and Hum, where he literally sings a line saying he heard a singer on the radio, that singer being Bruce Cockburn) but that line from “Lovers in a Dangerous Time” is powerful: we’ve got to kick at the darkness ’til it bleeds daylight. That is, Beth and I would say if we had the energy, on a good day, part of our understanding of our calling, part of why we sell the books we do. What the books we sell to you might help you do.

I could wax eloquent about Brian’s friendship, too, and we are grateful for that. But the point is to point BookNotes reader

s to Cockburn, who points, in his artful, suggestive way, to something Bigger. A gull-shaped shaped ship, perhaps, from the gorgeous song “All the Diamonds of This World” that carries us to sea. Or a Big Circumstance that, to this listener, and to Walsh’s, too, sounds like a Biblical sense of providence. Such a vision invites us into a subversive “feast of fools”—Cockburn got the line from theologian Harvie Cox— even as we live “out on the rim of the galaxy (where) “the gifts of the Lord lie torn – way out on the rim of the broken wheel.” Even as we believe it still is, as Bruce tells us, “a world of wonders.” Walsh helps us see how Cockburn sees, and that is, I’m sure, mostly a very good thing.

PART TWO

Kicking at the Darkness: Bruce Cockburn and the Christian  Imagination by Brian J. Walsh (Brazos Press) $18.99

Imagination by Brian J. Walsh (Brazos Press) $18.99

I have shared my passion for the artistic musicianship and provocative lyrical content of Bruce Cockburn, one of the most respected and awarded folk-rock-pop singers working today. I have shared that his music has brought pleasure and joy and spiritual insight to us for years, literally helping us find the courage to start our bookstore 30 years ago. There are very few pop artists working intentionally within the Christian tradition (U2 obviously comes to mind) that are as sophisticated lyrically and musically consistently as creative as any of the best recording artists of the rock era, so Cockburn means a lot to us.

I listed three reasons why you should buy the recent book by Brian Walsh, a Canadian author whose five previous books have all cited Cockburn. Walsh’s incredible new book, and his worldviewish and socially-engaged interpretation of Cockburn’s (mostly) serious work, stands not only as a good way to appreciate Cockburn, but will surely help you understand your Bible better, and will serve as an example of how to be discerning, artful, prophetic, as we interpret contemporary cultural artifacts. Whether you know or like Cockburn or not, this is, in a postmodern nod to C.S. Lewis, a great “experiment in criticism.”

One of the chief contributions that Brian offers is a theme that should be clear from the title: this is a book about the imagination.

Back when Walsh helped put the discussion about weltanschauung –worldviews–on the map of evangelicals, he taught us that worldviews are visions of and for life. That is, unlike others from Francis Schaeffer to his friend James Sire (not to mention the plethora of right-wing fundamentalists who started using the term), Walsh and his early co-author Richard Middleton, did not see worldviews as primarily abstract sets of ideas, a collection of static dogmas, hardly even “presuppositions.” He has from the beginning (in The Transforming Vision; IVP; $18.00) described worldview formation as a lived vision of the meaning of the story (or stories) we inhabit and how they inform our way of life, our implicit answers to life’s biggest questions. Our practices cycle back and shape how we see, and how we live. Worldviews are most fundamentally matters of the heart, and matters of the imagination.

This was clear (and for those who want the heavy background, it comes in part from Dutch Kuyperian philosopher, Herman Dooyeweerd (or see here) who wrote in the middle of the 20th century powerful critiques of the autonomy of reason, the idolatrous ideologies of Enlightenment notions of truth, themes later picked up by postmodern critics and folk like Stanley Hauerwas, Lesslie Newbegin, and even Alasdair MacIntyre.) When Walsh and Middleton wrote Truth Is Stranger Than It Used to Be: Christian Faith in a Postmodern Age (IVP; $22.00) it was the first and most singularly helpful book amid a batch of evangelical critics who failed to appreciate the deep challenge of deconstruction to the idols of Western rationalism. While D.A. Carson and others gripped about relativism and such, Walsh & Middleton said “good riddance” to modernity’s rationalist faith–to cite a Cockburn song they often used in workshops and speaking–because “The Candy Man’s Gone.” (from The Trouble with Normal.) If faith in progress through science and secularized Reason and economic growth ever was a worthy savior, by the time we began to see what Os Guinness called “the striptease of humanism” and felt the dis-ease of cultural disintegration, early signs of the downsides of globalization, the ecological crisis and the like, it was time for Christians to offer a clear “no” to capitalism and progress. Informed by Christian thinkers like the Dutch economist Bob Goudzwaard and Canadian social justice activist Gerry Vandezande, careful reformed thinkers like Richard Mouw and even aesthetic theorist Calvin Seerveld, Walsh became increasingly clear about denouncing our accommodation with the story of, values of, and truncated ways of living as we do in the standard consumerist North American way of life.

Trouble with Normal.) If faith in progress through science and secularized Reason and economic growth ever was a worthy savior, by the time we began to see what Os Guinness called “the striptease of humanism” and felt the dis-ease of cultural disintegration, early signs of the downsides of globalization, the ecological crisis and the like, it was time for Christians to offer a clear “no” to capitalism and progress. Informed by Christian thinkers like the Dutch economist Bob Goudzwaard and Canadian social justice activist Gerry Vandezande, careful reformed thinkers like Richard Mouw and even aesthetic theorist Calvin Seerveld, Walsh became increasingly clear about denouncing our accommodation with the story of, values of, and truncated ways of living as we do in the standard consumerist North American way of life.

By the time they started reading Bible scholar Walter Brueggemann, they were reminding us of the Biblical themes of exile, the role of lament in the Hebrew Scriptures, grappling with the “texts of terror” and wondering how the subversive ways of Jesus the servant King counter the violence supposed by many traditional Christians. Walsh and Middleton (and Brian’s wife Sylvia) are all scholars and teachers, but they were realizing that the best way to nurture a counter-cultural perspective among their students was to not just intone “no dualisms” and “creation-fall-redemption” to illustrate the wholistic redemptive plan of God to heal the entire cosmos, nor to do merely leftist or postmodern cultural criticism, but to find ways (a la Brueggemann) to enhance the  imagination. I don’t know if Brian would say this, but it seems that The Prophetic Imagination and The Hopeful Imagination, extraordinary, dense studies by Brueggemann, and his generative work on the Psalms (especially the Psalms of lament) funded a shift, a powerful, prophetic edge that has, I might note, gotten him into some trouble. Brian is a sweetheart of a guy, a good friend to many and a kind, gracious fellow, but he does speak his mind. And he despises the ways the church has failed to offer critique to the idols of the land, the way we can’t even imagine that things might be, as Bruggey taught us to say, otherwise. To awaken us from our slumber, we have to be aroused; apathy must be eroded by pathos. We need prophetic art to break us open.

imagination. I don’t know if Brian would say this, but it seems that The Prophetic Imagination and The Hopeful Imagination, extraordinary, dense studies by Brueggemann, and his generative work on the Psalms (especially the Psalms of lament) funded a shift, a powerful, prophetic edge that has, I might note, gotten him into some trouble. Brian is a sweetheart of a guy, a good friend to many and a kind, gracious fellow, but he does speak his mind. And he despises the ways the church has failed to offer critique to the idols of the land, the way we can’t even imagine that things might be, as Bruggey taught us to say, otherwise. To awaken us from our slumber, we have to be aroused; apathy must be eroded by pathos. We need prophetic art to break us open.

writing in free verse) to talk about a Christ-shaped imagination, helping us envision and embody a story that is shaped by the story of God. Yes we need

writing in free verse) to talk about a Christ-shaped imagination, helping us envision and embody a story that is shaped by the story of God. Yes we needthe poets to help us really “see” and dream a uniquely Christian worldview, lived in community in ways that says both “yes” and “no” to the practices and values of our age. And no poet/artist has influenced–or been used by–Walsh as much as Bruce Cockburn. When I said in my back-cover blurb that this book was years in the making, I know it is so. It comes from Walsh’s years of pondering and practicing, teaching and training, denouncing and dancing. (I will never forget how he dragged this lead-footed wall flower onto the dance floor when a cover band struck up “Brown Eyed Girl” but I digress.) Kicking at the Darkness is a book about what some might call a Christian worldview, or what might better be described as the nurturing of a radically faith-filled imagination. It is about dreams and dancing and denunciation.

In fact, it seems to me that anyone who follows the conversations about worldview would love  this book, whether you care much about Cockburn or not. I’m thinking of those who have read or knows about the excellent, if weighty, Worldview: A History of a Concept by David Naugle (Eerdmans; $30.00), the helpful, brief, Naming the Elephant by James Sire (IVP; $16.00), the fascinating Metaphors We Live By by George Lakoff (University of Chicago Press), the often-cited Creation Regained by Albert Wolters (Eerdmans; $14.00) or Nancy Pearcey and J. Mark Bertrand, who are equally important contributors to this area. I always appreciate Walsh’s fresh descriptions of how worldviews work, how stories shape us, and the relationship between the big worldview questions and the imagination and he says it well, again, freshly, in this new book. By the way, speaking of Brian’s renown on these very themes, I hope you know that the first portion

this book, whether you care much about Cockburn or not. I’m thinking of those who have read or knows about the excellent, if weighty, Worldview: A History of a Concept by David Naugle (Eerdmans; $30.00), the helpful, brief, Naming the Elephant by James Sire (IVP; $16.00), the fascinating Metaphors We Live By by George Lakoff (University of Chicago Press), the often-cited Creation Regained by Albert Wolters (Eerdmans; $14.00) or Nancy Pearcey and J. Mark Bertrand, who are equally important contributors to this area. I always appreciate Walsh’s fresh descriptions of how worldviews work, how stories shape us, and the relationship between the big worldview questions and the imagination and he says it well, again, freshly, in this new book. By the way, speaking of Brian’s renown on these very themes, I hope you know that the first portion  of N.T. Wright’s historic The New Testament and the People of God (Fortress; $38.00) comes largely from Walsh’s influence; it is not inconsequential that it is dedicated to him! Ends up the good former Bishop, by the way, besides a debt to Walsh, is quite the Cockburn fan himself.

of N.T. Wright’s historic The New Testament and the People of God (Fortress; $38.00) comes largely from Walsh’s influence; it is not inconsequential that it is dedicated to him! Ends up the good former Bishop, by the way, besides a debt to Walsh, is quite the Cockburn fan himself.

***

I think the beautiful Preface and the first two chapters of Kicking at the Darkness are worth the price of the book. In the first introductory chapter, “God, Friendship and Art”, Brian tells of the power and passion of Cockburn’s music and how enjoying and studying it has been so fruitful for him and his friends and students. (Another narration of this experience of the importance of music that is more heart-rending and revealing can be found in the moving introduction to the study Religious Nuts, Political Fanatics: U2 in Theological Perspective by Robert Vegacs where Walsh tells of gathering around friends in their hospital room as a newborn was dying, and how a U2 concert proved such a life-giving blessing.) In this first good chapter of Kicking… he has a section “On Worldviews” and explains “The Aesthetics of Generosity.” Excellent!

The second chapter is called “Ecstatic Wonderings and Dangerous Kicking: Imagination and Method” which sounds both allusive and a bit academic. Yes, there is this concern for methodology, but it isn’t dry. He begins to explore Bruce’s music right from the start, even as he describes his process, what he’s doing, what he is hoping to accomplish, how he plumbs the interaction of Bible, Bruce, and his own reading of both. This is rich stuff, interesting not only to Cockburn fans, but instructive for anyone doing any sort of cultural exegesis. He explains his “interpretive assumptions” and while one needn’t know how to spell hermeneutics, it is a crash course, a quick crash course that is balanced and insightful, wise and fair. What a fun way to learn, to be exposed to the art of interpretation, and to ponder how to most appropriately engage the arts.

His illuminating discussions in this chapter of songs like “Dancin’ in the Dragon’s Jaw” and “Creation Dream” and “Hills of Morning” are splendid, and it is good to start with perhaps Cockburn’s most popular album. (He played one of these songs on SNL in 1980—Bob Newhart was the host— and they remain standards.) Brian opens up their meanings, helps us realize the method of his madness, relating theology and art, Bible and culture, faith and social discourse.

His illuminating discussions in this chapter of songs like “Dancin’ in the Dragon’s Jaw” and “Creation Dream” and “Hills of Morning” are splendid, and it is good to start with perhaps Cockburn’s most popular album. (He played one of these songs on SNL in 1980—Bob Newhart was the host— and they remain standards.) Brian opens up their meanings, helps us realize the method of his madness, relating theology and art, Bible and culture, faith and social discourse.

From this strong beginning, Walsh digs a bit deeper, but the book does not proceed methodically through Cockburn’s canon, chronologically. Rather, each chapter chooses a theme, a metaphor or image that Brian discerns in Cockburn’s music, and draws from the breath of his catalog to play with the songs around the chapter’s theme. For instance, he has an amazingly interesting chapter on Cockburn’s “windows.” Who knew—even those of us who pay attention to Bruce’s lyrics, and discuss them at length–that there was so much about windows? And what a generative metaphor this is, for seeing, for vision, for light, for perspective. Walsh draws on more than a dozen songs (including Beth’s all-time favorite, “All the Diamonds”) and outlines several different sorts of window songs. This is very insightful about Cockburn’s journey, but, importantly, it offers ways to think about faith and formation and Christian engagement as we look at life.

Next, Walsh uses his exceptional insight about the Biblical teaching about creation, but not so much the ways in which creation is under threat by the unsustainable visions which lack any sense of faithful stewardship these days, the idol-driven assault which he explored with co-author Steve Bouma-Prediger in the important Beyond Homelessness (Eerdmans; $27.00.) He explores Cockburn’s insights about the creation under threat in a later chapter, a chapter that I would call a “must read.” Space does not permit us to even list the songs he covers here in this early chapter about the joy of creation and the “world of wonder” which we are given as gift (or the creative way he uses excerpts of Lewis’ The Magicians Nephew.) But it is a lovely, lovely chapter, and Brian’s own poetic rumination at the end is itself a gift of playful rhetoric and artful retelling.

Next, Walsh uses his exceptional insight about the Biblical teaching about creation, but not so much the ways in which creation is under threat by the unsustainable visions which lack any sense of faithful stewardship these days, the idol-driven assault which he explored with co-author Steve Bouma-Prediger in the important Beyond Homelessness (Eerdmans; $27.00.) He explores Cockburn’s insights about the creation under threat in a later chapter, a chapter that I would call a “must read.” Space does not permit us to even list the songs he covers here in this early chapter about the joy of creation and the “world of wonder” which we are given as gift (or the creative way he uses excerpts of Lewis’ The Magicians Nephew.) But it is a lovely, lovely chapter, and Brian’s own poetic rumination at the end is itself a gift of playful rhetoric and artful retelling. And so it goes, theme by theme, chapter by chapter. Here are a few that come next. (Do you know the song allusions? No matter–this is great stuff!)

At Home in the Darkness, but Hungry for Dawn

Into a World of Dancers

Humans (This is a study of one pivotal album, the 1980 release, Humans.)

Broken Wheel

Betrayal and Shame

What Do You Do With the Darkness? This is mostly a recapitulation, a poetic targum, a homily offered in the spirit of Cockburn’s own candor about brokenness and the reality of pain and dislocation in the fallen world. It is beautiful, and worth the price of the book.

Justice and Jesus

Waiting for a Miracle

In the glorious last few pages, Walsh summarizes—he’s an evangelist at heart, it seems, so there is some sermon

izing going on here—and throws in line after line from Bruce’s lyrics. Most have been discussed carefully in the book so readers will appreciate what they have evoked in Walsh and, if they know the songs, what they have evoked in their own listening. He leaves behind the quotation marks (assiduously used throughout) and allows the art to enter his own prose.

Despair is a doorway to hope. Hope transcends sentimental optimism because it refuses to avert its gaze from the darkness, refuses to repress that ache in the spirit we know as despair. Engaging the work of Bruce Cockburn, we have seen that this is a broken-wheeled world. We have seen the extremes of what humans can be. And we have heard a call to justice, to love, to fulfilling our calling as humans, creative, redemptive dancers in this dance of creation.

Where are we? In a world of wonders, called forth by love.

Who are we? We are angel beasts, rumors of glory, called to image the creator God of love.

What’s wrong? We live in the falling dark, a world of betrayal, idolatry, and ideology, hooked on avarice.

What’s the remedy? We’re given love and love must be returned. That love took on flesh in this glittery joker, dancing in the dragon’s jaws.

In a culture of captivated imaginations we need liberation. In a culture of dehydrated imaginations we need fresh water. In a culture that has lost its imagination we need new dreams. Bruce Cockburn’s art awakens such an imagination. And it is a Christian imagination.

Jesus, thank you, joyous Son.

BookNotesSPECIAL

DISCOUNT

any book mentioned

2O% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you wantinquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to knowHearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333