WHIPLASH

I suspect it was the work-world whiplash that I felt that first propelled me into thinking about the meaning of work. Let me explain.

I was raised in a pretty hard-working, no-nonsense family, and the motto of “work first, play later” was engrained in me early, with chores around the house and the three quarters of an acre on which we lived. In light of the boredom of picking up fallen sticks and limbs or rotten fallen fruit from our many trees, helping mom with wash, or mowing the lawn in summer’s heat, I sort of figured that’s just the way it was. Drudgery.

But then I got a job, right out of high school, as a camp counselor, doing work unlike any I ever heard of. All summer long I worked alongside the most amazing people I had ever met, serving severely disabled children and adults (who were also some of the most amazing people I ever met), adapting fun-loving, camp programing for those in wheelchairs of all shapes and sizes. I became a fan of the Easter Seal Society, became a special ed major, and loved those crazy, long hours at Camp Harmony Hall, for four consecutive summers. I visited the camp a bit that fifth summer, since Beth was working there at the time, and in between my training for campus ministry with the CCO in Pittsburgh, I’d drive (or hitch hike) to help out a bit at Harmony Hall and, mostly, to pester my bride-to-be. We both loved that camp job, even as demanding as it was on body and soul, and came to realize what my father used to tell me: work could be deeply rewarding, true service; work could be innovative, work could be with great people, work could meaningful, it could matter. You should enjoy it. And work was not about making money.

people I ever met), adapting fun-loving, camp programing for those in wheelchairs of all shapes and sizes. I became a fan of the Easter Seal Society, became a special ed major, and loved those crazy, long hours at Camp Harmony Hall, for four consecutive summers. I visited the camp a bit that fifth summer, since Beth was working there at the time, and in between my training for campus ministry with the CCO in Pittsburgh, I’d drive (or hitch hike) to help out a bit at Harmony Hall and, mostly, to pester my bride-to-be. We both loved that camp job, even as demanding as it was on body and soul, and came to realize what my father used to tell me: work could be deeply rewarding, true service; work could be innovative, work could be with great people, work could meaningful, it could matter. You should enjoy it. And work was not about making money.

Since we made so little in wages at Harmony Hall, I worked long hours at a lumber mill makings skids for a month between getting out of college and heading to camp, for my “real” summer job. And there, amidst the saw mills and forklifts, which we called tow motors, pulling boards from conveyor belts set too fast, stacking skids on graveyard shift, the people were surly, the work loud and dangerous, and the workplace a setting of palpable alienation and frustration. Unlike Harmony Hall, the exhaustion at the end of the day carried no sense of blessing or gladness. The contrasts made my head spin.

month between getting out of college and heading to camp, for my “real” summer job. And there, amidst the saw mills and forklifts, which we called tow motors, pulling boards from conveyor belts set too fast, stacking skids on graveyard shift, the people were surly, the work loud and dangerous, and the workplace a setting of palpable alienation and frustration. Unlike Harmony Hall, the exhaustion at the end of the day carried no sense of blessing or gladness. The contrasts made my head spin.

As James Taylor later sang in the deeply moving song about a woman who worked in a shoe factory in Lowell, Massachusetts (“Millworker” from the album Flag.) “I let that manufacturer use my body as a tool.”

I didn’t need Karl Marx to explain that this isn’t the way it ought to be. James Taylor gave voice to it in a way that still brings tears to my eyes, reminding me of that short season at the sawmill and the truth that for many, perhaps most people, labor is less than meaningful, too often dangerous, and nearly dehumanizing. Unions helped in some places, and the 1980’s new age emphasis on personal fulfillment and aesthetics, even, has helped. The latest trends in business and management books remind leaders to help their employees exercise their gifts, take pride in their work, contribute to the corporate ethos and, perhaps, even the common good.

These popular tendencies are wonderful, mostly, and were the sorts of reforms I pondered back in the late 70s, thinking about the whiplash, going from the conveyor belt and “units produced” work at the planing mill for an owner I never met, to the caring, creative, life-giving world of work in camp (and, later, the free-wheeling CCO campus ministry, and, for a season, the wild political activism of the Thomas Merton Center, where I had a desk and a coffee pot.) Work can be hard and deathly or it can be hard and life-giving. Sadly, too many do not experience their jobs as a blessing, nor see their work as being a blessing to others. Most don’t see their life-work as mattering much more than getting financially reimbursed for something they’d rather not be doing. In a fallen world, such are the deformities of our views of work and such are the dysfunctions of many a factory, cubicle, or clinic.

When we opened our bookstore 30 years ago — talk about long hours with low pay, don’t get me started — we had a category of books about work (and it has expanded considerably, year by year.) I don’t know if other Christian bookstores had such a section, but I gather that most did not. Sales reps that would visit our store were perplexed or astounded. I recall that first month stocking Working, the powerful collection of often sad interviews by Studs Turkle, a couple of profound and prophetic books published by the Christian Labour Association of Canada, and a few by the early Lutheran spokesperson for “thinking Christianly” about work, William Diehl. I wish his Thank God It’s Monday and The Monday Connection were still in print!

Although I have been seriously interested in this topic, we have not always been able to live out this vision of the reformation of work and the workplace with as much energy or grace as I’d wish. Marx may call it alienation, but the Bible calls it sin and idolatry. We live East of Eden and are all living out our faith — even the most idealistic entrepreneurs or social innovators — in ways that are, as my friend Steve Garber puts it, “clay-footed.” I know this.

And so, we talk about these things, organize events, sell books (list those listed here or here.) I believe we’ve helped a little, and you, too, by buying these books, have helped create a new conversation about these things. I hear it in congregations and conference, in campus ministries and in Bible study groups. From places like The High Calling blog to The Washington Institute of Faith, Vocation and Culture, to Jubilee Professional, we are hearing great voices, see good examples, all inviting us to these sorts of concerns. If your church or ministry hasn’t joined these conversations, now is a good time to start. And this book is a good one to use.

* * * *

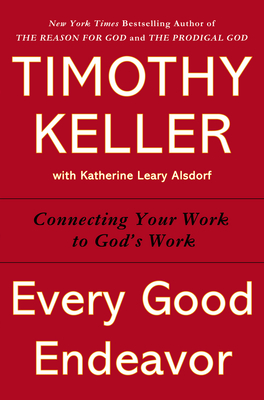

It is with very deep gratitude and gladness that I announce what is surely one of the most important books of the year, Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work by Timothy Keller with Katherine Leary Alsdorf (Dutton; regularly $26.95. Our sale price $19.95.) There have been a plethora of books on calling and vocation and work, specifically, in the last decade, and some are outstanding. (You know how often we recommend The Call by Os Guinness. See our list here for annotations of favorites such as Work Matters by Tom Nelson, Kingdom Calling by Amy Sherman, How Then Shall We Work by Hugh Whelchel and several by Paul Stevens, among so many others.)

It is with very deep gratitude and gladness that I announce what is surely one of the most important books of the year, Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work by Timothy Keller with Katherine Leary Alsdorf (Dutton; regularly $26.95. Our sale price $19.95.) There have been a plethora of books on calling and vocation and work, specifically, in the last decade, and some are outstanding. (You know how often we recommend The Call by Os Guinness. See our list here for annotations of favorites such as Work Matters by Tom Nelson, Kingdom Calling by Amy Sherman, How Then Shall We Work by Hugh Whelchel and several by Paul Stevens, among so many others.)

With such an embarrassment of riches and so many

good books on this, we wonder, as we do sometimes with other book categories, too, if there really needs to be more written on this? Why this book by this author? Is it really essential? What more can be said, no matter how urgent the topic?

Allow me to list three things generally, that make me grateful for this new book, and three things more specifically that I believe Every Good Endeavor adds to the faith/work conversation. (That’s six reasons you should buy it, folks — do I need to write more to persuade you? How ’bout this: it’s on sale for a bit better than 25% off here at BookNotes. The Hearts & Minds order form link is at the end of this review.)

THREE REASONS THIS IS A MAJOR GIFT TO THE FAITH/WORK CONVERSATION

Firstly, it is written by Tim Keller. I do not mean to be glib or sensational, but he is one of the more important religious writers of our generation — The New York Times has suggested that he is a modern-day C.S. Lewis, Publisher’s Weekly has noted his “encyclopedic learning” and the exceptional success of his faithful church planting in Manhattan (Redeemer Presbyterian and its City-to-City Network) is an indication that he is a voice to be heard, a leader to whom we should listen, a writer of serous import. Fan or not of his conservative Calvinism, his missional urban vision, his traditional sensibilities (he’s no Rob Bell, for instance) Keller is a thoughtful writer, himself well-read and attuned to sociological matters alongside his love for the Bible and theology, so he brings a certain contemporary weight to the books he writes. They are not heady or arcane or academic, but they are not chatty and upbeat, either. They are mature, important, uniformly good, in my view. That Keller has weighed in on this topic is so good for the larger movement, and it is good to have his thoughtful views on this vexing, urgent matter. Keller has a lot of fans, and he could have written next on any number of topics. His long-standing passion for this topic, of course, is illustrated by his church sponsorship of The Center for Faith and Work. He’s not jumping on a bandwagon here nor is he new to thinking about this. He’s a neo-Calvnist who quotes Kuyper, after all and some suggest that it is this emphasis on culture engagement that has allowed his ministry to flourish so near to Wall Street and Broadway.

more important religious writers of our generation — The New York Times has suggested that he is a modern-day C.S. Lewis, Publisher’s Weekly has noted his “encyclopedic learning” and the exceptional success of his faithful church planting in Manhattan (Redeemer Presbyterian and its City-to-City Network) is an indication that he is a voice to be heard, a leader to whom we should listen, a writer of serous import. Fan or not of his conservative Calvinism, his missional urban vision, his traditional sensibilities (he’s no Rob Bell, for instance) Keller is a thoughtful writer, himself well-read and attuned to sociological matters alongside his love for the Bible and theology, so he brings a certain contemporary weight to the books he writes. They are not heady or arcane or academic, but they are not chatty and upbeat, either. They are mature, important, uniformly good, in my view. That Keller has weighed in on this topic is so good for the larger movement, and it is good to have his thoughtful views on this vexing, urgent matter. Keller has a lot of fans, and he could have written next on any number of topics. His long-standing passion for this topic, of course, is illustrated by his church sponsorship of The Center for Faith and Work. He’s not jumping on a bandwagon here nor is he new to thinking about this. He’s a neo-Calvnist who quotes Kuyper, after all and some suggest that it is this emphasis on culture engagement that has allowed his ministry to flourish so near to Wall Street and Broadway.

A second general reason I think Every Good Endeavor is vital and good is because it is rooted in the community of leaders at the Center for Faith and Work; again, there has been a decade of careful teaching, lots of listening, good explorations and networking going on, and this book is in some ways the fruit of their intentional outreach into various career areas. That their much-loved Director Katherine Leary Alsdorf co-authored this, a bit, with Reverend Keller is significant. Katherine worked in the high-tech business world for years, even before her own profession of faith, and knows well the joys (and struggles) of being both successful and of failing in the business world. (Katherine’s behind-the-scenes husband, too, for what it is worth, has extraordinary experiences, having studied at Union Theological Seminary and having worked in the business world in “the city” as New Yorker’s call their home turf.) Ms Alsdorf is passionate and kind, deeply rooted in a gospel-centered sort of discipleship, but she has walked where many lay people have walked; some of her story is told in the introduction to Every Good Endeavor and it is riveting. She knows what it is like to be an agent of God’s ways in corporate America. It is rare that someone embodies theological, spiritual, and business savvy as she does, and this book brings such depth and expertise to us all. It will be taken seriously by those in the corporate sector who read it because Keller and Alsdorf have listened and studied well. They know what their talking about. Watch a short video clip of Katherine Alsdorf talking about work in Christian perspective, here.

of failing in the business world. (Katherine’s behind-the-scenes husband, too, for what it is worth, has extraordinary experiences, having studied at Union Theological Seminary and having worked in the business world in “the city” as New Yorker’s call their home turf.) Ms Alsdorf is passionate and kind, deeply rooted in a gospel-centered sort of discipleship, but she has walked where many lay people have walked; some of her story is told in the introduction to Every Good Endeavor and it is riveting. She knows what it is like to be an agent of God’s ways in corporate America. It is rare that someone embodies theological, spiritual, and business savvy as she does, and this book brings such depth and expertise to us all. It will be taken seriously by those in the corporate sector who read it because Keller and Alsdorf have listened and studied well. They know what their talking about. Watch a short video clip of Katherine Alsdorf talking about work in Christian perspective, here.

Thirdly, I believe that Keller does bring something a bit unique in terms of perspective and tone, and that is, in fact, this gospel-centered, foundational teaching that our vocational lives are a response to, and grounded in, the grace of our Triune God, shown in the saving work of Jesus Christ. We are adopted as sons and daughter of God and the atoning work of Christ allows us to be free from idols and anxieties. As we trust God’s goodness and look to the gospel for strength and formation of character, we can be (dare I say it) radical agents of social transformation. As Keller properly put it in his recent Generous Justice, Christ’s justification makes us just. There is no glorious triumphalism here, but a humble reliance on the cross. As those claimed as beloved by God, we now can work not for prestige or power or wealth, but to serve Christ’s Kingdom, for God’s glory. I’m a fan of John Piper’s chapter “Serving God in the 9 to 5” in his passionate Don’t Waste Your Life, and this book has a bit of that tone — we think hard about this stuff, but in a way that is warmly dedicated to God’s reputation, responding to God’s gospel grace, gladly clear that we find joy in honoring God, 9-to-5. As one early reader put it, this book reaches both your heart and your mind. Obviously, we like that a lot.

social transformation. As Keller properly put it in his recent Generous Justice, Christ’s justification makes us just. There is no glorious triumphalism here, but a humble reliance on the cross. As those claimed as beloved by God, we now can work not for prestige or power or wealth, but to serve Christ’s Kingdom, for God’s glory. I’m a fan of John Piper’s chapter “Serving God in the 9 to 5” in his passionate Don’t Waste Your Life, and this book has a bit of that tone — we think hard about this stuff, but in a way that is warmly dedicated to God’s reputation, responding to God’s gospel grace, gladly clear that we find joy in honoring God, 9-to-5. As one early reader put it, this book reaches both your heart and your mind. Obviously, we like that a lot.

So, this handsome new hardback, Every Good Endeavor, is important simply because it is written by Tim Keller, and it thereby adds his fame and reputation to the faith/work movement. He is a good writer, so this is a very good thing. And it is important because it is co-authored by a very sharp woman, who has extraordinary stories of and connections within the secular work-world. Further, thirdly, I think we can say that this book is both hard-headed and soft-hearted, grounded as it is in radical gospel transformation. I don’t think it is exactly a “spirituality of work” but it does remind us that we join our work to God’s work because of God’s gracious overtures and the gospel’s effective power in our lives. I like the caliber and tone, and highly recommend it.

THREE SPECIFIC CONTRIBUTIONS YOU WILL APPRECIATE The previous three affirmations are general — important, but general. That the book is written by an esteemed theological writer, that it emerges from real-life experiences of an effective and fairly sophisticated marketplace emphasis, co-authored by a mature business woman, and is grounded in gospel truth shows why I think it is to be taken serious, studied, discussed, shared.

The previous three affirmations are general — important, but general. That the book is written by an esteemed theological writer, that it emerges from real-life experiences of an effective and fairly sophisticated marketplace emphasis, co-authored by a mature business woman, and is grounded in gospel truth shows why I think it is to be taken serious, studied, discussed, shared.

But what, exactly, do Keller and Alsdorf bring to the table?

For starters, I just love the way the book (without saying it, really) is arranged by the popular theological windows, emerging from the very flow of the Biblical narrative, namely, creation

, fall, redemption.

The first part of this book (including four good chapters) lays a very solid foundation based on what Keller headlines as “God’s Plan for Work.” Many books hint at this, and the best explicate it, and this does an excellent job. Chapter One and Two are, respectively, “The Design of Work” and “The Dignity of Work.” I adored the next two chapters (points that we do not hear nearly enough, I’m afraid) that work is both cultivation and service. God’s original plan for work, seen in the Genesis creational mandate itself, is, in fact, a cultural mandate. Preachers will get good mileage from these truths, and workers of all kinds will be challenged to keep these in mind. We are developing, also in our work, the good potential God has put into the world (shades of Andy Crouch’s wonderful Culture Making) and we do this as service to God and neighbor. Is your work serving somebody? I hope you can see the connection. These chapters (and their good footnotes) will help.

Next, this book is candid about the deformations and dysfunctions, the idols and ideologies, the clay-footedness and stupidity let loose in the world. That is, it is realistic about the fall, about the state of the human condition. This section is called “Our Problems with Work” and in it Keller brilliantly shows how work becomes fruitless and how work becomes pointless. There is a serious chapter exploring how work becomes selfish. That work reveals our idols has never been developed much before and this singular insight is worth the price of the book and could provide good, honest conversations among those reading it together. (Do you know his important book Counterfeit Gods on money, sex, and power? There are shades of that book here.) Every Good Endeavor is not the only Christian book about the work-world that is realistic, sobered by the hard times in which we live. But it does help us ruminate on that, connecting some dots, understanding what we most likely can and cannot do, even with the best intentions.

Happily, the book ends with four great chapters (created as only a good preacher can) showing the relationship of the gospel and work. Here we get “A New Story for Work,” “A New Conception for Work,” “A New Compass for Work,” and “New Power for Work.” I don’t want to spoil it by naming the many items he approaches here, but it is detailed, drawing on great books (and popular culture) and social critics. He reflects on how we view institutions, explains implications of the doctrine of common grace, challenges us to think about ethics and integrity, and moves in large ways towards important themes. It is very insightful and very inspiring.

From the good plan of God to the hard news of sin to the exciting news of a Kingdom approach, these three units offer a great structure for a great book, and Keller plumbs this well. It isn’t a cheap structure or a casual one, it is profound. His astute teaching about all this helps us see that. Like other things in life — from sex to art, science to politics — we can see what is good and wondrous, what is sinful and broken, and what is being redeemed by gospel transformation, and how to take up our vocations into the world in wise and proper ways. This is the story of the God’s redemptive work in the world and is how we take up the calling, as in his subtitle, to relate our daily work to God’s work.

Besides this essential, generative, worldviewish flow of the structure of the book, allow me to note this, again: the content in each of these sections is suburb, a bit more sophisticated than some such books, but without being too abstract or intellectual. From the Biblical insight of the design and purpose of work to the hardships of toil and alienation in the section on our difficulties, Keller is not glib or simplistic. This is good stuff, and important. There are good stories, helpful illustration, and a delightful array of fabulous footnotes, icing on the cake.

Finally, there is a very useful appendix, designed, it seems, for pastors and teachers, campus ministers or leaders. It is about how to help others relate faith and work, and it chronicles just a bit of the work of Redeemer’s Center for Faith and Work. There is a chart there showing the shifts in thinking that must happen for this to work well (and it is a chart you will want to photocopy and ponder.) This describes a bit of their efforts to encourage artists, business people, IT people, professors, health care providers, educators and the like. It isn’t a handbook or curriculum, but it does point you towards ways to keep this conversation going, how to help faith communities grapple with the implications of a work-world mission, and how to disciple others, forming them into a wholistic Kingdom vision.

WHIPLASH OR DISCONNECT? THIS CAN HELP

Maybe you have experienced whiplash, moving from a rewarding, joyful job of meaningful service to others to hard, tedious work that seems almost exploitative. Or, maybe you’ve experienced another sort of whiplash, just going from an idealistic and glorious faith community one day to a harsh and realistic job site the next. Anyway, there are disconnects galore, and we believe that God is pleased whenever we try to live more integrated lives, relating life and faith, creation and redemption, Sunday and Monday. God is pleased by “every good endeavor” that we offer and we are glad to be able to offer this wonderful new book that explores these themes with clarity and wisdom, by an author and co-author we enjoy and respect. May Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work (regularly priced at $26.95 but on sale at BookNotes for $19.95 be a blessing to many. After all, as that old James Taylor songs reminds us, “a young girl ought to stand a better chance.”

service to others to hard, tedious work that seems almost exploitative. Or, maybe you’ve experienced another sort of whiplash, just going from an idealistic and glorious faith community one day to a harsh and realistic job site the next. Anyway, there are disconnects galore, and we believe that God is pleased whenever we try to live more integrated lives, relating life and faith, creation and redemption, Sunday and Monday. God is pleased by “every good endeavor” that we offer and we are glad to be able to offer this wonderful new book that explores these themes with clarity and wisdom, by an author and co-author we enjoy and respect. May Every Good Endeavor: Connecting Your Work to God’s Work (regularly priced at $26.95 but on sale at BookNotes for $19.95 be a blessing to many. After all, as that old James Taylor songs reminds us, “a young girl ought to stand a better chance.”

DISCOUNT

Every Good Endeavor

(Timothy Keller)

25%+ off

regular price $26.95

sale price $19.95

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street

Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333