In our last post here at BookNotes I ruminated a bit (or was it a rant?) about how our bookstore’s unique inventory and category-busting ethos are, to some extent at least, marked by the influence of what some call neo-Calvinism, or Kuyperianism. That is the movement of those working with the intellectual tools and spiritual impulses of the early 20th century Dutch public intellectual and civic leader, Abraham Kuyper, perhaps most popularly represented by Al Wolters’ book Creation Regained (Eerdmans; $15.00) or Brian Walsh & Richard Middleton’s still essential Transforming Vision (IVP; $17.00.)

bookstore’s unique inventory and category-busting ethos are, to some extent at least, marked by the influence of what some call neo-Calvinism, or Kuyperianism. That is the movement of those working with the intellectual tools and spiritual impulses of the early 20th century Dutch public intellectual and civic leader, Abraham Kuyper, perhaps most popularly represented by Al Wolters’ book Creation Regained (Eerdmans; $15.00) or Brian Walsh & Richard Middleton’s still essential Transforming Vision (IVP; $17.00.)

Kuyper’s followers have engaged in a vigorous re-appropriation of Reformed theology into a culturally engaged worldview calling for the renewal of all of culture around various spheres of life, learning to think distinctively about everything.

(This short piece by Gideon Strauss entered my inbox just this week, a good example of a Kuyperian consideration of why an office chair matters, and the theology gleaned from the use of it. Or, consider this brilliant manifesto of James K.A. Smith about his role in our beloved Comment magazine, a prime example of the neo-Cal vision if ever there was one. Or, please, enjoy one of a good friend’s most powerful little pieces, written a few days ago, about a talk he was asked to give about vocation and ethics in the multi-national business world. Garber is Reformed and Kuyperian and brings in the likes of Os Guinness and Wendell Berry and Jean Valjean.)

That kind of stuff just gets me up in the morning. Sometimes keeps me up at night, too. How about you?

Well, after explaining in my last BookNotes post how this particular tradition influenced us and helped to set the vision for our bookstore, we quickly reviewed four new books about Kuyper himself. They are pretty great books and I hope you at least read my reviews of them.

I will soon offer a longer essay about our evaluation of all this, and our minor role in this Kuyperian movement which I’ll post under the “columns” tab at the website. It will include a description of what I consider to be one of the very best serious books about Kuyperianism and how it contributes to various modern issues and compares with other contemporary social theologies. Look for that soon.

Okay, okay, you may be thinking. Enough about the old Dutch guy and his followers with hard to spell names. We realize that Kuyperian worldview thinking is a valuable thing, a vital sort of neo-Calvinism which tells the story which invites us to seek God’s ways “in but not of” the world, in all areas of culture. It offers a robust, thick, sort of perspective and approach that demands discernment and intellectual engagement in every zone of life. We get it.

THE BEST IN EACH FIELD

I really do not mean to overstate this kind of neo-Calvinism, and as you know, we are more ecumenical than most. But I have my list of favorite Christian books that are seminal and extraordinary in their specialized fields, and most are frankly influenced by this working tradition. For instance, just think of Michael Schutt’s essential Redeeming Law: Christian Calling and the Legal Profession (IVP) or Calvin Seerveld’s legendary book on the arts, Rainbows for the Fallen World (Toronto Tuppence) or Del Ratz’s Science and Its Limits (IVP) or Steve Bouma-Prediger’s For the Beauty of the Earth (Baker) or Quentin Schultze’s Communication for Life (Baker) or David Koyzis’ Political Visions and Illusions (IVP) or Bill Romanowski’s Eyes Wide Open: Finding God in Popular Culture (Brazos) or Mark Noll’s History Through the Eyes of Faith (HarperOne) or John Van Dyke’s The Craft of Christian Teaching (Dordt) or Jeff Van Duzer’s Why Business Matters to God (IVP.) Each one of these are the very best in their fields, beautifully and profoundly integrating faith and their academic discipline and are absolutely foundational for further Christian thinking in their subject area. And are influenced by this whole Kuyperian worldview life-is-religion tradition.

Redeeming Law: Christian Calling and the Legal Profession (IVP) or Calvin Seerveld’s legendary book on the arts, Rainbows for the Fallen World (Toronto Tuppence) or Del Ratz’s Science and Its Limits (IVP) or Steve Bouma-Prediger’s For the Beauty of the Earth (Baker) or Quentin Schultze’s Communication for Life (Baker) or David Koyzis’ Political Visions and Illusions (IVP) or Bill Romanowski’s Eyes Wide Open: Finding God in Popular Culture (Brazos) or Mark Noll’s History Through the Eyes of Faith (HarperOne) or John Van Dyke’s The Craft of Christian Teaching (Dordt) or Jeff Van Duzer’s Why Business Matters to God (IVP.) Each one of these are the very best in their fields, beautifully and profoundly integrating faith and their academic discipline and are absolutely foundational for further Christian thinking in their subject area. And are influenced by this whole Kuyperian worldview life-is-religion tradition.

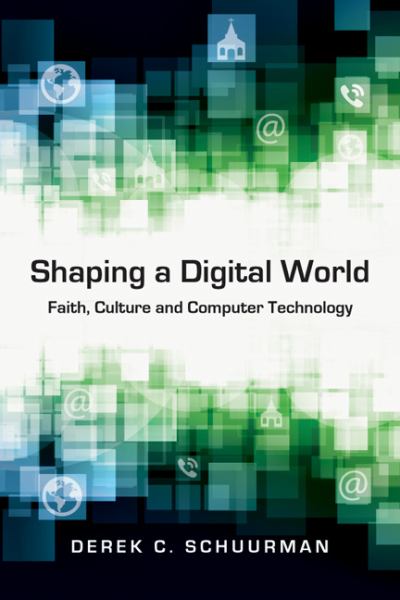

And now a new one just has been added into this essential list! It is doubtlessly the best Christian book in its field.

S haping a Digital World: Faith, Culture and Computer Technology by Derek C. Schuurman (IVP Academic; $18.00) This is brand new and it is truly a one-of-a-kind resource, a book that, drawing on the tools and insights of the Kuyperian movement, is able to be wiser than any other book on the subject. I think it is simply a must-read, not only for those who work in this field, but, frankly, for almost all of us, since we all live in a technological society and a digital milieu.

haping a Digital World: Faith, Culture and Computer Technology by Derek C. Schuurman (IVP Academic; $18.00) This is brand new and it is truly a one-of-a-kind resource, a book that, drawing on the tools and insights of the Kuyperian movement, is able to be wiser than any other book on the subject. I think it is simply a must-read, not only for those who work in this field, but, frankly, for almost all of us, since we all live in a technological society and a digital milieu.

There are other books that I like in this field, and each have their own strengths and reasons we should enjoy and learn from them. We all swim in this topic, but, oddly, I am afraid don’t read much about it. Nicholas Carr’s The Shallows: What the Internet Is Doing to Our Brains (Norton; $15.95) is up to date and beautifully written, even as he warns about the dangers of reading on line. I do hope you have bought it (or at least read the famous article he wrote, “Is Google Making Us Dumb” — it is so important! I hope you know Sherrie Turkle’s wonderful, wonderful Alone Together: Why We Expect More From Technology and Less from Each Other (Basic Books; $16.99.) Leonard Sweet always takes you on an energetic road trip of learning, and you will end up excited by the possibilities of our hot-wired world by reading his optimistic Viral: How Social Networking Is Poised to Ignite Revival (Waterbrook; $14.99.) Information Technology and Cyberspace by David Pullinger (Pilgrim Press; $18.95) is a dense and serious book, grounded in a more liberal theological background, important for what it does, bringing together ethics and theology. I appreciate that it thinks deeply about fundamental things.

The Next Story: Life and Faith after the Digital Explosion by Tim Challies (Crossway; $19.99) is a great effort at bringing together a balanced, worldviewish, culturally savvy evaluation, informed by solid theological insights and offering nearly pastoral guidance. He covers most of the requisite topics — information overload, distraction, the need for discernment. I highly recommend it; some will be challenged if they haven’t seriously considered a Godly perspective on their digital lives, although it isn’t as serious as it might have been. Please do check it out — we take it to most book tables and displays we do these days.

From the Garden to the City: The Redeeming and Corrupting Power of Technology by John Dyer (Kregal; $13.99) is actually a quite recent gem which I hope gets to be better known — we just discovered it! It draws a bit on the important work of Albert Borgman, and it is obvious that the author has done serious reading in the field — Heidegger, McLuhan, etc. He works in computer science and he has explored the whole “media ecology” schools. Best of all, he has this great vision of how the Bible works, which, as we will see, is one of the great strengths of Schuurman’s book. (And Dyer is at the dispensational Dallas Theological Seminary – my, how times are changing!) I hope to write more about it, as it gets a whole lot right, and is quite well written. I do think it is a very good book, helpful in many ways. I will be eager to see if Dyer reviews Schuurman. I suspect that Schuurman didn’t cite Dyer’s good book because it wasn’t released when he was finishing the manuscript.

I have regularly said that anyone who uses computers should read one that is exquisite, a wise book called Habits of the High-Tech Heart: Living Virtuously in the Information Age by Kuyperian media specialist at Calvin College, Quentin J. Schultze (Baker; $22.00.) It isn’t a study of the field of computer science, precisely, but a guide for anyone who interfaces (as they say) with the digital world. I re-read it recently and it remains a truly exemplary book, helping all of us guard our hearts and develop faithful dispositions and practices. Kuyperian that he is, he has a grand and reliable vision, but the topic is about virtue and faithful presence, mostly. It is a great book, but doesn’t set out to do what Derek Schuurman does.

wise book called Habits of the High-Tech Heart: Living Virtuously in the Information Age by Kuyperian media specialist at Calvin College, Quentin J. Schultze (Baker; $22.00.) It isn’t a study of the field of computer science, precisely, but a guide for anyone who interfaces (as they say) with the digital world. I re-read it recently and it remains a truly exemplary book, helping all of us guard our hearts and develop faithful dispositions and practices. Kuyperian that he is, he has a grand and reliable vision, but the topic is about virtue and faithful presence, mostly. It is a great book, but doesn’t set out to do what Derek Schuurman does.

Each of these are good in their own way, but they offer only a piece of the puzzle, or they offer inspiration without doing serious re-thinking about the presuppositions of the field itself. Or they do so with an imbalance, an imbalance that makes the final book less righteous than it ought to be. Schuurman’s Shaping a Digital World gets it all spot on, as they say. It is clearly written, profound, and very, very helpful. Especially for those who work in the field (programs, engineers, mathematical folks) is is simply a must. And, as I will explain, for many, many of us as well.

Here are four things that make this new book truly extraordinary.

FIRST: HIS PROPER USE OF THE BIBLE AS AN UNFOLDING STORY First, I appreciate the way Schuurman uses the Bible to shape its argument, not by coming up with simplistic proof-texts or narrow moral constraints, but by being formed by the biggest truths of the Scripture. He is a math and computer science professor (with a PhD in electrical engineering, having done scholarly publishing in that field.) But he teaches at the Kuyperian-influenced neo-Cal college, Redeemer, in Ancaster, Ontario. So he gets the worldview- shaping structure of God’s promise and deliverance story in the Bible. It is his colleagues there, Michael Goheen and Craig Bartholomew who wrote extraordinary The Drama of Scripture: Finding Our Place in the Story of Scripture (Baker Academic; $21.99) after all. You may know the spiffy, simplified, and abridged version (with discussion questions) The True Story of the Whole World: Finding Your Place in the Biblical Drama (Faith Alive; $13.99) No wonder sciency-guy Schuurman gets it right, hanging around these these Biblical visionaries.

First, I appreciate the way Schuurman uses the Bible to shape its argument, not by coming up with simplistic proof-texts or narrow moral constraints, but by being formed by the biggest truths of the Scripture. He is a math and computer science professor (with a PhD in electrical engineering, having done scholarly publishing in that field.) But he teaches at the Kuyperian-influenced neo-Cal college, Redeemer, in Ancaster, Ontario. So he gets the worldview- shaping structure of God’s promise and deliverance story in the Bible. It is his colleagues there, Michael Goheen and Craig Bartholomew who wrote extraordinary The Drama of Scripture: Finding Our Place in the Story of Scripture (Baker Academic; $21.99) after all. You may know the spiffy, simplified, and abridged version (with discussion questions) The True Story of the Whole World: Finding Your Place in the Biblical Drama (Faith Alive; $13.99) No wonder sciency-guy Schuurman gets it right, hanging around these these Biblical visionaries.

One of the themes of Kuyperian neo-Calvinism is the way in which Scripture holds together as one coherent unfolding story. We sometimes talk about the four acts in the Biblical drama, the four chapters of the story: first, there is a blessedly good creation and humans tasked with developing it and then a radical fall which curses everything, but the plot moves towards a wholistic redemption with the bodily resurrection of Christ assuring the last chapter, the full scope of final restoration.

This coherent creation-oriented, Christ-centered account of the story of the drama of God’s plan of cosmic redemption is often explained this way these days. Marva Dawn has used this approach for years. Brian McLaren wrote a fantastic novel about it (The Story We Find Ourselves In, published by Jossey-Bass.) Sean Gladding has a book and video curriculum called The Story of God, The Story of Us (IVP.) N.T. Wright popularized it although I’ve heard it earlier from Brian Walsh and Sylvia Keesmaat (both of whom influenced Tom early on, as he has often admitted.) In the excellent The Next Christians (Multnomah) Gabe Lyons has a succinct section showing why we need the four-chapter approach (creation/fall/redemption/restoration) rather than the typical two-chapter (fall/redemption) definition of the gospel, and how this is the way to help the current generation understand their faith. He clearly has Kuyperians to thank for teaching him this.

approach for years. Brian McLaren wrote a fantastic novel about it (The Story We Find Ourselves In, published by Jossey-Bass.) Sean Gladding has a book and video curriculum called The Story of God, The Story of Us (IVP.) N.T. Wright popularized it although I’ve heard it earlier from Brian Walsh and Sylvia Keesmaat (both of whom influenced Tom early on, as he has often admitted.) In the excellent The Next Christians (Multnomah) Gabe Lyons has a succinct section showing why we need the four-chapter approach (creation/fall/redemption/restoration) rather than the typical two-chapter (fall/redemption) definition of the gospel, and how this is the way to help the current generation understand their faith. He clearly has Kuyperians to thank for teaching him this.

Back when I was learning the neo-Calvinist lingo of rejecting dualism and see the full unfolding Biblical “story” as an alternative to reading the Bible piecemeal, the phrase “creation/fall/redemption” became short-hand for expressing the storied nature of the Bible and a hint towards the Kingdom vision that insists that it is this good creation that God so loved, this world that Jesus died to redeem, that it is the very real groaning creation (Romans 8) that will someday be set free, into renewed shalom, along with some of its cultural artifacts. A historical-redemptive “method” of discerning the broader Biblical story is so much more commonplace these days and everybody from Roman Catholics to Nazarenes to Anabaptists have published fantastic books that highlight the contours of the Biblical drama, describing it as “redemption history” and calling us to find our place in the unfolding story of which we are yet still a part.

I say all this to note that Derek Schuurman uses this four-chapter “drama of Scripture” structure to analyze the nature of technology; it becomes the very way he formats the chapters of Shaping a Digital World. And this works really, really well.

(This format reminds me of the explicit structure of Lewis Smedes’ wonderfully-written and well-thought out, classic book Sex for Christians [Eerdmans; $20.00] which likewise uses the “made good, messed up by sin, but substantially restored in Christ” – creation/fall/redemption approach to his topic. What an insightful and sensible way to lay out a book. It worked well for the eloquent Mr. Smedes, despite the title that some find rather dumb, and it works well for Schuurman as well.)

Christians [Eerdmans; $20.00] which likewise uses the “made good, messed up by sin, but substantially restored in Christ” – creation/fall/redemption approach to his topic. What an insightful and sensible way to lay out a book. It worked well for the eloquent Mr. Smedes, despite the title that some find rather dumb, and it works well for Schuurman as well.)

Schuurman shows, to put it too simply, how the possibility of computer science, and the structures that shape it (rooted as they are in God’s created order) are essentially good (God made the world “very good” after all.) He helpfully does this in a great chapter called “Computer Technology and the Unfolding of Creation”

and it is beneficial not only for those interested in technology, but as an example of a great way to be shaped by this foundational teaching of the Bible. I wish other scholars and authors writing in other fields read this chapter as an example of how to start a book.

And, yet, the very structures and possibilities that emerge from a good creation, developed by humans made in the image of a good, creative God, are marred by sin. Everything is messed up, distorted by idols and ideologies, shaped by sinful people in a broken world. Things are, as Cornelius Plantinga puts it in his amazing book about sin “not the way it’s supposed to be.” Again, the neo-Calvinist worldview helps him immensely here as he is not surprised, nor devastated, by the realities of sin. It is interesting how so many Christian books either understate or overstate the impact of sin in our world. Schuurman understands how sinful ideas and practices can lead to distorted values and ideologies. He can name these, insightfully help us understand their contours and impact, and in this, he preforms a prophetic task. Others have explored the downsides of our digital age, but Schuurman gets it particularly right. He has drawn on the best social critics (Turkle, Postman, Ellul, et al) and frames them in light of the Bible’s own teaching about sin and idolatry and hubris and the like. That exceptional chapter is on the way the fallen nature of our world effects the doing of science and it is solid and wise and interestingly informative.

And, yes, in Christ, God has launched his Kingdom project. The promise of Revelation — “all things new” — is the truest truth! What good news! God is faithful and in God’s grace, through Christ, in the power of the Spirit, we get to “sing to the Lord a new song” which is to say we get to use our God-given intelligence, insight, creativity and passion to help bring new social initiatives, healing, helpful plans, fresh, good ideas, into the marketplace of ideas. Even technology and computers can be redeemed, touched with the healing influence of the cross and resurrected Christ. The chapter “Redemption and Responsible Computer Technology” is brilliant, and this is where the previous two chapters — the goodness seen in the sustained nature of the created order and the propensity to sin and wrong-headedness in our fallen world — combine, allowing Schuurman to explore responsible agency. Just how do we live in this area, knowing what we know? What a question!

He makes plain that we are not to be romantic idealists wishing for a pre-fallen world, but neither are we pessimists, merely lamenting the messiness of the complexities of our damaged culture. We don’t opt out of modern projects but neither do we except everything to be gloriously proper. We must learn to navigate our role in society — and in this case, our use of computer technologies, and our engagement with the whole digital scene — with “in the world but not of it” prudence and hope.

Some day, computer science will be used in the new creation, in glory to the Lamb and in service to all. This world and parts of our culture will be redeemed. For a beautifully explored case study of this very topic ( I just have to interject) see the little but life-changing book When the Kings Go Marching In: Isaiah and the New Jerusalem by Richard Mouw (Eerdmans; $15.00) And don’t forget the wonderfully rich, very insightful rumination on this by Andy Crouch in his essential Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (IVP; $25.00.) Dr. Schuurman quotes both of these great books and his own eschatology vision for technology is itself very nicely developed. My, this is good. It’s pretty neat to have an electrical engineer and math teacher talking about God’s redemptive promises to renew all creation, eh?

service to all. This world and parts of our culture will be redeemed. For a beautifully explored case study of this very topic ( I just have to interject) see the little but life-changing book When the Kings Go Marching In: Isaiah and the New Jerusalem by Richard Mouw (Eerdmans; $15.00) And don’t forget the wonderfully rich, very insightful rumination on this by Andy Crouch in his essential Culture Making: Recovering Our Creative Calling (IVP; $25.00.) Dr. Schuurman quotes both of these great books and his own eschatology vision for technology is itself very nicely developed. My, this is good. It’s pretty neat to have an electrical engineer and math teacher talking about God’s redemptive promises to renew all creation, eh?

But we are not there yet. We still inhabit this world laden with possibility and danger. His chapter about the future is itself quite exciting, hopeful, sober, but he warns about the potential issues, and offers keen and balanced insight as we move towards robotics, 3-D computers, civilian use of drones and the like. (Can anybody say Google Glass?) Schuurman looks at artificial intelligence, the theories of Ray Kurzweil, and playfully explores some science fiction stuff. He knows all about the Turing Machine and the halting problem. His writing here is not so in-depth that those of us who aren’t into this scene will be lost, but it is informed enough to be of interest even to sci-fi fanatics, futurists, math geeks and AI experts.

Again, Schuurman avoids the two extremes of Luddite negativity or utopian optimism. Created, fallen, redeemed, and someday restored – this is the story told by any neo-Calvinist/Kuyperian scholar worth his or her salt. Schuurman helps us see technology, and specifically, computers, in this light. Such insight is worth its weight in gold. As I have suggested, there are no accessible books on this topic which explain this so well and have these Biblical/theological categories so overtly in place.

SECONDLY: HE COMPARES & CONTRASTS OTHER VIEWS

A second strength makes this book very helpful. One of the strengths of neo-Calvinist or Kuyperian thinking (although it can be annoying if it gets too prideful) is the custom of illustrating how other traditions haven’t given the fullest account of things in God’s world. In other words, the helpfulness of Schuurman’s neo-Calvinist approach is contrasted with other writers who, in his estimation, get it less than right, get stuck on the horns of dilemmas, or inevitably fail to give a fully proper theological account. In this case, Dr. Schuurman is gracious and, I think, nearly brilliant. He affirms the very best of other authors, engages them well (if in a cursory fashion) and honors their work, showing how their particular insights can be used, even if they aren’t the whole story. And then he shows why their contribution isn’t fully adequate.

For instance, there are critics of technology who have a looming Biblical blind spot. Jacques Ellul comes to mind. He is a very, very important writer, and we stock most of his many books. Yet, he is always negative, critical, disbelieving that God can (or desires to) redeem the stuff of earth. This makes him amazingly astute in prophetic denunciation of idols and ideologies, but less useful when it comes to offering alternatives. He’s strong on the nay-saying, but weak on much positive.

At the risk of oversimplifying, consider how Ellul’s book on communication suggests that media is always propaganda (that is the title of that book of his.) His book on cities suggests that cities are not grounded in the good creation, and therefore something normative, but, rather, are signs of Babel and always bad. Ditto with his view of politics: it is always violent, necessarily the abuse of power. His book on technology, of course, exposes the idol of reducing everything to technique; it’s mostly bad. So, again, he is helpful in exposing what has gone wrong, what is dangerous and inappropriate and bad. (And we need this prophetic edge, more now than ever, I’d say!)

media is always propaganda (that is the title of that book of his.) His book on cities suggests that cities are not grounded in the good creation, and therefore something normative, but, rather, are signs of Babel and always bad. Ditto with his view of politics: it is always violent, necessarily the abuse of power. His book on technology, of course, exposes the idol of reducing everything to technique; it’s mostly bad. So, again, he is helpful in exposing what has gone wrong, what is dangerous and inappropriate and bad. (And we need this prophetic edge, more now than ever, I’d say!)

I only say all this to help you see that when Schuurman evaluates Ellul’s important work, he is both appreciative, but shows that Ellul can’t muster the resources

to offer much that is positive; there are precious few norms to guide the development of a redemptive kind of technological work in the world for Ellul (and that may be because he simply doesn’t have a good view of creation; like many liberation theologians, he reads the Bible as if it begins after the fall.) Ellul, and those who espouse his approach, basically say, as Nancy Reagan put it regarding teen sex, “just say no.”

Schuurman explains that neo-Calvinist philosophy in the line of Kuyper (such as the aforementioned Herman Dooyeweerd) offers intellectual tools to see into the reality of God’s ordered world, and thereby can come up with norms or principles that help us determine appropriate technological design and use. With a robust theology of creation, one can imagine ordinances built into the world that can be opened up for positive guidance in doing stuff faithfully. That is, we don’t have to only say “no.”

(He doesn’t go into it too much, but this is important for him. With Scripture as lenses, we can see into the realities of God’s creation, discerning His ordinances for, in this case, prudent, responsible, multi-dimensional technological design. Interestingly, some would say that there is somewhat of a parallel here with the Roman Catholic methodology of determining principles from natural law.)

Anyway, Professor Schuurman (teacher and engineer that he is) shows you how it works and lays out design principles — a multitude of them, including aesthetic ones, for instance — and ways to create great programs and normative digital platforms for human flourishing. This is truly remarkable, that he offers not only this richly Biblically-informed vision of the meaning of culture, technology, and computers, but he offers proposals and principles for opening up God’s intentions for these technologies, computing for shalom, if you will. He not only tells you what all means, but offers wise, normative guidelines for faithful advancement of the field. In other words, he does a lot more than sound the warnings or tell you to be spiritually careful.

It takes a neo-Calvinist, I’d say – can somebody prove me wrong, here? – to offer a book like this, one that is robustly and equally convinced of the goodness of the structures of science and the dangers of the sinfulness of the direction it has been developed, and yet is also hopeful about the possibility of a reformation of the field. In really simple parlance, he tells you what’s right, what’s wrong, and what, in faith, we might do about it all.

As you yourself have probably discerned, even from watching movies or advertisements, even, some nearly make demons out technology, others almost make idols out of it. Some are too pessimistic, some nearly utopian. They overstate the evil or the potential. Better, is knowing, really knowing, deep in one’s spiritual bones, how the Biblical truths of “creation-fall-redemption” allows us imagination to at least get this right; we needn’t be Luddites or utopians. We don’t have to give up computers a la Wendell Berry nor wax eloquent about their spiritual potential a la Kurzeweil or the crew from Wired. And so, Schuurman can truly appreciate Ellul (and he does!) and those in his wake (Neil Postman, God bless him, or Borgman or Berry.) But he doesn’t fall for the gnostic heresy that there is something wrong with this creation, per se. Sin is a parasite on a good creation, and any thing in life – computers, in this case – can be (must be, if we are to get it right) seen as made good, distorted by sin, and being redeemed and restored by the resurrected Christ. We have to move beyond critique to re-formation!

This is one example of why Shaping a Digital World: Faith, Culture and Computer Technology is unlike any other accessible book in this field of technology, and the only book like it in the field of computer science. That it draws on books like Al Wolter’s Creation Regained (Eerdmans; $16.00) and uses its Kuyperian lingo of creation/fall/redemption, allows it to be balanced and intregal and extraordinarily helpful, not falling off into either extreme. Because it can hear the critique of the idols and the distortions caused by technology (indeed because it can name them so well) without lingering in the dangers, it becomes useful. That is, it isn’t just another abstract critique about the ideas of a technological society, but it offers practical guidance for new practices, norms for faithfulness in this field.

It sounds boring to say it is well balanced, so I won’t say just that. It would be a blessing to have a book that is both critical and appreciative. But Shaping a Digital World isn’t just “balanced” — it is stunningly insightful, extraordinarily fresh, radically integrated, wisely multi-faceted, practical and full of prophetic imagination!

Interestingly, writers from an earlier generation of reformational scholars have done good work on the philosophy of technology, including the prolific and weighty Egbert Schuurman, whose several significant books we stock and whose books Douglas helpfully cites.

on the philosophy of technology, including the prolific and weighty Egbert Schuurman, whose several significant books we stock and whose books Douglas helpfully cites.

It was, in fact, Dutch neo-Calvinists at Calvin College in Grand Rapids (at their Center for Christian Scholarship) who in the late 1970s, perhaps inspired to come up with a more balanced and multi-dimensional and positive assessment of technology in contrast to Ellul and Stringfellow and Postman, who, with Egbert Schuurman (from Borger, Holland, I might add) undertook a multi-disciplinary project out of which came the one-of-a-kind Christian book on engineering, Responsible Technology: A Christian Perspective edited by Stephen Monsma (Eerdmans; $27.00.) Responsible Technology may be just a bit dated now, but is still the go-to, best-of book for anyone looking through the eyes of Christian faith at the topic of engineering and industrial design. If you are a metallurgist, civil engineer or industrial designer, or involved in the economics or public policy of this arena, that book is a must! Again, there is nothing like it.

balanced and multi-dimensional and positive assessment of technology in contrast to Ellul and Stringfellow and Postman, who, with Egbert Schuurman (from Borger, Holland, I might add) undertook a multi-disciplinary project out of which came the one-of-a-kind Christian book on engineering, Responsible Technology: A Christian Perspective edited by Stephen Monsma (Eerdmans; $27.00.) Responsible Technology may be just a bit dated now, but is still the go-to, best-of book for anyone looking through the eyes of Christian faith at the topic of engineering and industrial design. If you are a metallurgist, civil engineer or industrial designer, or involved in the economics or public policy of this arena, that book is a must! Again, there is nothing like it.

The next generation Schuurman, by the way, is easier to read, I think, than his namesake and I’m grateful for his clarity and passion. And, of course, his focus is on digital technologies and computer science. He draws on the seminal Calvin Center’s Responsible Technology: A Christian Perspective and the philosophical work of Egbert Schuurman, but updates it well, taking its reforming orientation and prophetic insights into the digital world of the 21st century.

THIRDLY: MULTI-DIMENSIONALITY INSTEAD OF REDUCTIONISM

cally useful, but it should also be aesthetically pleasing and environmentally sound, facilitating relationships, with proper legalities, etc.)

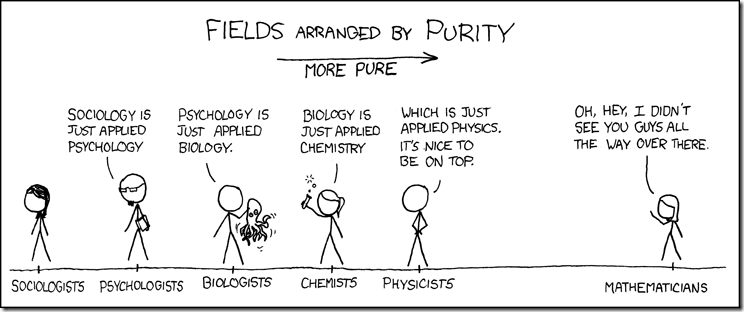

Attention to this helps us prevent “reductionism” (one of the devilish characteristics of Western modern culture, it seems, and something that scholars as diverse as C. S. Lewis and Albert Einstein, Michael Polanyi and Leslie Newbegin all railed against.) By using Dooyeweerd’s modal scale, and its structure of norms and laws that hold each dimension in relation to the other, Schuurman is able to give us a picture of how good computing works. Whether one is a programmer or website designer or a typical browser and typer, this study of the very structure and dimensions of this slice of life is amazingly insightful. I really enjoyed it, and hope you would too.

Here is one quote where he reminds us of the nature of a multi-dimensional approach, an approach he thinks is grounded in the way God wants us to think about his vastly interesting and coherent creation:

Computer scientists and engineers who spend much of their time looking at the world through the narrow lens of logic and algorithms must avoid tunnel vision. God’s world is much more complex and diverse. Even though many things possess computable attributes,they cannot simply be reduced to numbers. This notion is captured well by William Cameron, who wrote, “It would be nice if all of the data which sociologists require could be enumerated because then we could run them through IBM machines an draw charts as the economists do. However, not everything that can be counted counts and not everything that counts can be counted.” The attempt to reduce created reality to something that can be computed is a form of reductionism.

FOURTHLY: DELIGHTFULLY CLEAR AND INSPIRING There is a fourth reason why this is a book that I find so helpful, so good, illustrative of the sorts of books we are most excited about. It is serious, but not too demanding to read. It is enjoyable. It is pleasantly well written. Dutch neo-Calvinist philosphy isn’t usually know for its lovely prose, and the Kuyper stuff can get dense. (Kuyper’s own work, of course, is translated from Dutch, from a hundred years ago, which is never simple.) Yet Shaping a Digital World by Derek C. Schuurman shines. The author is a good communicator, passionate about his task, and clearly excited about teaching us to think faithfully about it. It is not dumbed down, but it isn’t overly abstract or arcane, either. Again, this is just the kind of book we most thrilled about, educated, interesting, faithful, helpful.

There is a fourth reason why this is a book that I find so helpful, so good, illustrative of the sorts of books we are most excited about. It is serious, but not too demanding to read. It is enjoyable. It is pleasantly well written. Dutch neo-Calvinist philosphy isn’t usually know for its lovely prose, and the Kuyper stuff can get dense. (Kuyper’s own work, of course, is translated from Dutch, from a hundred years ago, which is never simple.) Yet Shaping a Digital World by Derek C. Schuurman shines. The author is a good communicator, passionate about his task, and clearly excited about teaching us to think faithfully about it. It is not dumbed down, but it isn’t overly abstract or arcane, either. Again, this is just the kind of book we most thrilled about, educated, interesting, faithful, helpful.

Shaping… is based on a very wide reading of the germane literature, it brings various schools of thought into dialogue, it takes seriously the insights of thinkers who may not be fully correct about everything, but who have something valuable to contribute. That is to say, it is gracious and open. And, yet, it is passionate about trying to frame the discussion in light of God’s good care for the world, the Bible’s insights, the need for uniquely Christian scholarship. Dare I say it is holy? Yes, this work is done on holy ground; Schuurman’s approach is an act of worship. I am glad for this heart-felt conviction, and I am glad for the teacherly clarity. You will even be glad for the copious and interesting footnotes. It really is a very nice book.

And, there is a website that has some discussion questions and other resources to help you through the book. Visit the book’s webpage, here.

Some other authors may be more super-spiritual, pious, and inspirational as they gloss over hard work needed to be done in this field. Other books may be more critical, passionately rejecting the reductionism and dangers of digital culture, alarmingly so, heavy in their critiques. Few get it right, though, offering a vibrant reading of the good, the bad, the ugly, faithful and hopeful. Few books so clearly call for good and beautiful and multi-dimensional reformation of the very art and science of computer use. I am not kidding when I say this book is exemplary in nearly every way, and that every field of study would be so fortunate as to have such a young, learned, wise, and creative writer to guide us into the basics of a truly Christian approach to their field. Kudos to IVP Academic for acquiring this kind of manuscript, and kudos to Schuurman for offering it to us.

I’m sure you know somebody who is eager to learn about a Christian philosophy of technology, especially information science and digital domains. Most people reading this use computers a lot, I’d bet, so maybe this would be helpful, a good reading experience for you.

technology, especially information science and digital domains. Most people reading this use computers a lot, I’d bet, so maybe this would be helpful, a good reading experience for you.

Perhaps you even know somebody who is eager to learn more about what we

mean by neo-Calvinism, wanting to see a contemporary example of a young

Kuyperian in action. Maybe you continue to be intrigued by the mix of titles and suggestions we make here at Hearts & Minds. This is a great example of the sort of thing we most appreciate.

I also bet you know somebody who needs a good, practical example of how to “think Christianly” about a subject, how to study and evaluate and make contributions that are fundamentally shaped by Biblical faith, but that doesn’t (mis)use the Bible as some kind of cheap handbook. How about suggesting it as an option for your next book club? Or, start a reading group!

Christian students wanting to bone up on the whole process of doing Christian cultural analysis, Christian professors who haven’t quite figured how to integrate faith and learning/teaching or maybe someone writing a paper, drafting a study document, or even authoring a book about the nature of our times would all benefit from this, I’m sure.

If you work with youth, young adults, or in campus ministry I’d say this is as good of a book as you can find that relevantly gets at this proper view of thinking Christianly, engaging culture, the doctrines of creation-being-regained, living with Kingdom hopes as “salt and light” disciples. If I were such a youth or college pastor, I’d have a few on my shelf. Unless you want your young friends to go through life not thinking critically or Christianly about one of the major influences in their entire world!

For any of these folks, Shaping a Digital World is a good resource. May its vision be considered, its content be discussed, and its suggestions be embodied, for the sake of our own faithful presence in the world, corem deo, for the sake of our neighbors, and for the glory of God. Calvinist, Kuyperian or not, we all want that, right?

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333

read@heartsandmindsbooks.com