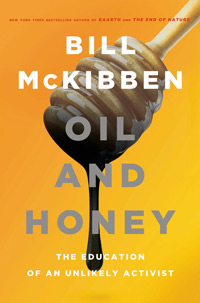

Oil and Honey: The Education of An Unlikely Activist Bill McKibben (Times Books) $26.00

20% OFF BookNotes discount = $20.80 (reviewed by Hearts & Minds Bookstore owner Byron K. Borger.)

I have long appreciated the books of Bill McKibben, from his haunting first one, the award-winning End of Nature through his Eerdmans release The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job and the Scale of Creation, his lovely hiking stories and nature writing prose, and his increasingly passionate books about global warming (Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet) and how to live with climate change. He is literate and kind and although not a farmer, brings to mind quite naturally the writing of his agrarian friends Wendell Berry and Wes Jackson. It isn’t every writer whose essays gets an anthology, but there is the great collection,The Bill McKibben Reader. I’ve often recommended his lovely and inspiring book Hope, Human and Wild: Stories of Living Lightly on the Earth. McKibben’s new book called Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist (Times Books; $26.00) is spectacular and I recommend it heartily for several reasons.

have long appreciated the books of Bill McKibben, from his haunting first one, the award-winning End of Nature through his Eerdmans release The Comforting Whirlwind: God, Job and the Scale of Creation, his lovely hiking stories and nature writing prose, and his increasingly passionate books about global warming (Eaarth: Making a Life on a Tough New Planet) and how to live with climate change. He is literate and kind and although not a farmer, brings to mind quite naturally the writing of his agrarian friends Wendell Berry and Wes Jackson. It isn’t every writer whose essays gets an anthology, but there is the great collection,The Bill McKibben Reader. I’ve often recommended his lovely and inspiring book Hope, Human and Wild: Stories of Living Lightly on the Earth. McKibben’s new book called Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist (Times Books; $26.00) is spectacular and I recommend it heartily for several reasons.

Per usual, a bit of background, if you will indulge me. I want you to know why I feel so strongly about this book, and why it should be on your list, to be read as soon as possible.

In the early 1980s the eloquent, thoughtfully passionate writer Jonathan Schell did a series of pieces in the New Yorker called The Fate of the Earth which then was expanded into an exceptionally respected and prestigious book of the same title. It speculated on the horrific implications of the nuclear arms race and the vast consequences such as “global winter” if such modern hydrogen bombs were ever detonated. Those of us who were already involved in faith-based, anti-nuclear weapons work took odd inspiration from this awful book; like the classic Hiroshima by John Hershey (written in 1946) it was, we felt, an honest wake-up call and offered some vindication of why we saw ourselves as watchers on the walls like in Ezekiel 37, crying out warnings of real danger and God’s disapproval. Ragtag groups like ours in Pittsburgh were doing Bible studies with the likes of Philip Berrigan and doing research for Sojourners who led the way in the witness against the building of weapons of mass destruction and policies that promised a manufactured Apocalypse. I found myself often talking with those who worked in the military industrial complex as well as those who had been active in marches with Dr. King a decade or so previous.

Mainline protestant church groups – most notably the United Methodists and the Presbyterians – followed the leadership of the Roman Catholic bishops who had very publicly condemned the sin of building and intending to use weapons that would violate the historic just war theories. Those within the long-standing peace tradition of the Mennonites, Brethren and Quakers and their ministries such as “Every Church a Peace Church” took heart. Our resistance to bloated military budgets and neutron bombs and evil policies of intending the mass murder of civilians started to catch on. Faith and peacemaking was in the news; we traveled, we studied, we protested and prayed and lobbied. We cited Jesus and Paul, Polycarp and Francis, Bonhoeffer and John Paul, Dorothy Day and Oscar Romaro, Ron Sider and Billy Graham (who eventually condemned the use of the nukes.) It was nearly all consuming and it wasn’t fun or pleasant.

bloated military budgets and neutron bombs and evil policies of intending the mass murder of civilians started to catch on. Faith and peacemaking was in the news; we traveled, we studied, we protested and prayed and lobbied. We cited Jesus and Paul, Polycarp and Francis, Bonhoeffer and John Paul, Dorothy Day and Oscar Romaro, Ron Sider and Billy Graham (who eventually condemned the use of the nukes.) It was nearly all consuming and it wasn’t fun or pleasant.

But as the arms race grew and wars seemed to crop up on every continent and the nation went into debt to fund our increasingly expensive weaponry, the wider culture debated these things, and churches dug deeper into their Bibles. “Do not serve gods of metal,” Leviticus warned, and advanced weapons systems such as the horse drawn chariot – invented by the Assyrians – were forbidden from use by God’s people. A friend of mine researched Micah 1:13 and some word plays about the city of Lachish, where such dehumanizing weapons were stored and we pondered what it meant that God said that this was “the beginning of sin for you.” We came to understand the famous verse “be still and know that I am God” as a call to cease striving for military superiority (look it up!) and took seriously the command to “beat swords into plowshares.”

We didn’t need Brueggemann’s Prophetic Imagination (although it helped) to realize that sometimes our faith leads us to shed subversive tears. There was so much goodness to which we could say “yes” in this life (new babies coming into our lives, for instance) but sometimes it is important also to say “no.” We read Martin Luther King and studied Gandhi and experimented in campaigns of civil disobedience. I fell in love with Romans 12:1-2, inviting us with our very bodies to resist the ways of the world, and to thereby discover a spirituality of daily discipleship that was culturally engaged, used our minds, and yes noticeably nonconformist.

I say all this to note three things about Bill McKibben and his new book about being “an unlikely activist.”

FIRSTLY: THIS IS URGENT AND SERIOUS

Bill McKibben’s first book, The End of Nature, was likened upon its release in 1996 to Schell’s earlier Fate of the Earth. It, however, did not incite a national movement of urgency to reverse our carbon output, the toxins in the air and water, or the dangers of what came to be known as climate change. The polar ice caps are melting, sea levels continue to rise, drought and dangerously bad weather is unusually routine now, all over the world, year after year. McKibben was a helpful voice in 1996, a prophet among us, but we did not heed his plea. (He was not alone, of course: here is a long BookNotes bibliography I did a few years ago showing a healthy number of good books on faith-based creation care and Biblical stewardship.)

1996 to Schell’s earlier Fate of the Earth. It, however, did not incite a national movement of urgency to reverse our carbon output, the toxins in the air and water, or the dangers of what came to be known as climate change. The polar ice caps are melting, sea levels continue to rise, drought and dangerously bad weather is unusually routine now, all over the world, year after year. McKibben was a helpful voice in 1996, a prophet among us, but we did not heed his plea. (He was not alone, of course: here is a long BookNotes bibliography I did a few years ago showing a healthy number of good books on faith-based creation care and Biblical stewardship.)

We should have paid as much attention to him then as we did, say, to Pennsylvania writer Rachel Carson, whose 1962 classic Silent Spring catapulted us to resist the corporations who were recklessly dumping DDT into our food chain in the mid-60s. Mr. McKibben’s new Oil and Honey has some updated facts and very compelling information about why we simply must reduce our carbon emissions and the radical, consumerist lifestyles that fail the Biblical call to good stewardship, although it is not a sustained explanation of the crisis (as is his must-read book with the oddly spelled title, Eaarth.) But it is perhaps a more exciting and inviting way into the topic as it is loaded with stories and passion and risk and hope and drama. We should listen to McKibben, as we did with Carson and Schell, and this is an excellent place to start.

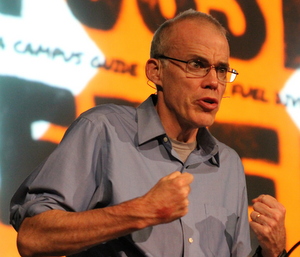

McKibben’s “unlikely” leadership in the work against environmental pollution and climate change has given him the gravitas and the issue generates the urgency that seemed to animate many of us in the anti-war and 70s anti-nuclear power movements — cue Jackson Browne’s powerful song “Before the Deluge” (or the sad new version by Eliza Gilkyson) — and it is obvious the the book is urgent and morally serious.

SECONDLY: DAVID VS GOLIATH DRAMA UP CLOSE

Secondly, Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist tells the story of McKibben starting a last ditch effort of nonviolent civil disobedience to galvanize resistance to the development of Tar Sands dirty oil in Canada and the controversial Keystone XL Pipeline which would obviously hook us more deeply into high-polluting fossil fuel technologies. (For those few readers who will recall, Dutch Reformed, neo-Calvinist friends in Canada in the Committee for Justice & Liberty (CJL) led by the late Gerald Vandezande, made similar arguments about Biblical stewardship, First Nation’s rights, and unhelpful views of progress against the proposed MacKenzie Valley Pipeline, leading to a moratorium in 1976.)

Although it is actually only half of the book – the “oil” part, I suppose one could say – it is riveting. You will be on the edge of your seat reading McKibben’s telling about dreaming up this scheme, the letter sent out by a dozen environmental leaders calling for direct action at the White House, forming solidarity groups, explaining “why we can’t wait” (to borrow a title of the book Martin Luther King wrote after his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” argument for Gandhian nonviolent resistance campaigns as a viable form of social change.) There simply has not been such a grass roots outcry on environmental issues in decades, if ever, and it is exciting to see if it will unfold, with McKibben consulting with national leaders, grass roots folk, kids with social media savvy. As you may know, it developed much more quickly than he ever expected. With good humor and gusto, he tells of the protests, the police, the scary first days in jail, the waves of new protesters who arrived in DC day after day after day and their (short) jail stays, logistics of all sorts, and the subsequent (fascinating) media work. (Some of this is quite entertaining, like his telling of being on Colbert.) And then there was the not surprising but still shocking push back from the oil industry, TransCanada, and others, the millions of dollars spent in favor of the pipeline, the lobbyists hired, the blatant and dishonest disregard for facts — the book is eye-opening here, too. This is not new, of course (some congressmen like John Boehner have taken over $2 million from big energy. See Dirty Energy Money for the ugly truth about who takes what from these super-rich, stop-at-nothing corporations.) Visit 350.org here.

title of the book Martin Luther King wrote after his “Letter From a Birmingham Jail” argument for Gandhian nonviolent resistance campaigns as a viable form of social change.) There simply has not been such a grass roots outcry on environmental issues in decades, if ever, and it is exciting to see if it will unfold, with McKibben consulting with national leaders, grass roots folk, kids with social media savvy. As you may know, it developed much more quickly than he ever expected. With good humor and gusto, he tells of the protests, the police, the scary first days in jail, the waves of new protesters who arrived in DC day after day after day and their (short) jail stays, logistics of all sorts, and the subsequent (fascinating) media work. (Some of this is quite entertaining, like his telling of being on Colbert.) And then there was the not surprising but still shocking push back from the oil industry, TransCanada, and others, the millions of dollars spent in favor of the pipeline, the lobbyists hired, the blatant and dishonest disregard for facts — the book is eye-opening here, too. This is not new, of course (some congressmen like John Boehner have taken over $2 million from big energy. See Dirty Energy Money for the ugly truth about who takes what from these super-rich, stop-at-nothing corporations.) Visit 350.org here.

Anyone who wonders what it is like being a national organizer in a David vs Goliath kind of battle, a grass roots idealist, what these sorts of public protests are like or the particular story of the weeks of daily anti-Keystone arrests at the White House that summer, will find Oil and Honey illuminating. What a fascinating tale of these ordinary folks, mostly politically liberal, trying to pressure Obama against all odds to live up to his environmental campaign promises (Obama has not been very good on environment policies, as I suppose you know and maintains a cozy relationship with big banks and big oil.)

McKibben’s story is told wonderfully, and I felt things, anxious things deep in my bones as I read, emotions I thought I had put to rest decades ago, about my feeble and short-lived involvement with those doing civil disobedience to expose the dangers of the arms race. If you have been involved in any large scale campaigns – pro-life protesting, anti-war activism, working on civil rights, fighting sexual trafficking, anti-porn picketing – you will love his good-humored and in some cased very candid glimpses behind the scenes. It felt very real to me, the fear, the self-doubt, the nervous jokes, the hope, the danger, the concerns about public image and effectiveness, the sense of doing something important and necessary and good, despite the consequences. Oil and Honey is a year-long memoir, more than embedded journalism, but advocacy written as social history, a primer on grassroots social change from the inside.

I love the tone of this book. McKibben is a person of faith, is fairly realistic about what might be accomplished by these public witnesses and stints of civil disobedience, is not unaware of criticisms and the temptations that accompany this sort of work, and he reports generously on a broad swath of the movement – from Sierra Club leaders to Native American activists to Nebraska ranchers worried about the aquifers, to brave but aging World War II veterans who were arrested with signs around their necks saying “WWII Vets: Handle With Care.” When he wrote about how he hoped people would dress up nicely to be arrested (this is serious and dignified business, he insists, as did King before him) and how exciting but also draining it was to train people in nonviolence and peaceful protest, and how darn hot and claustrophobic the paddy wagons can be, and how painful those plastic cuffs can be, I knew I wanted to keep reading. Parts reminded me of the must-read classic about the Montgomery bus boycott, Kings famous first book Stride Toward Freedom. (Here is a letter McKibben and Wendell Berry had written a year or so previous, in calling for civil disobedience at a coal fired plant in DC. It is instructive to read what they say.) You very well may want to keep reading, too, even if this sort of thing is very foreign to you. Believe me, it was foreign to the mild-mannered Methodist college teacher and outdoorsman from Vermont as well.

might be accomplished by these public witnesses and stints of civil disobedience, is not unaware of criticisms and the temptations that accompany this sort of work, and he reports generously on a broad swath of the movement – from Sierra Club leaders to Native American activists to Nebraska ranchers worried about the aquifers, to brave but aging World War II veterans who were arrested with signs around their necks saying “WWII Vets: Handle With Care.” When he wrote about how he hoped people would dress up nicely to be arrested (this is serious and dignified business, he insists, as did King before him) and how exciting but also draining it was to train people in nonviolence and peaceful protest, and how darn hot and claustrophobic the paddy wagons can be, and how painful those plastic cuffs can be, I knew I wanted to keep reading. Parts reminded me of the must-read classic about the Montgomery bus boycott, Kings famous first book Stride Toward Freedom. (Here is a letter McKibben and Wendell Berry had written a year or so previous, in calling for civil disobedience at a coal fired plant in DC. It is instructive to read what they say.) You very well may want to keep reading, too, even if this sort of thing is very foreign to you. Believe me, it was foreign to the mild-mannered Methodist college teacher and outdoorsman from Vermont as well.

THIRDLY: SURPRISE

Thirdly, I introduce McKibben’s work and O&H by recalling the dramatic years of often anguishing resistance to nuclear holocaust (not to mention the stupidity and deceit experienced close up during the crisis of TMI) because there is a splendid feature of the book – a second story that McKibben tells alongside the narrative of the protests and lobbying against the Keystone Pipeline – that is beautiful, lovely, fascinating and enjoyable to read.

T his second, overlapping narrative is not only fun to read, but brings into important clarity a huge, huge matter for any of us who are involved as public figures, who travel, teach, try to shape public opinion, whether we are social activists or armchair pundits. It is an issue I fretted about years ago during the height of the cold war, and still do to some extent. The issue is how to stay (for lack of a better word) normal in the face of a pressing historical crisis. Unless one is called to extraordinary sacrifice in these serious times, most of us have kids to play with, gardens to keep, laundry to do. We shop, send facebook updates to friends, we watch movies, we coach Little League, we go to music lessons with our kids (or for ourselves, if we are brave in mid-life.) We have birthday parties and funerals and church and work and important arguments about college football or major league baseball. There are lawns to mow and cars and pets and loved ones to care for.

his second, overlapping narrative is not only fun to read, but brings into important clarity a huge, huge matter for any of us who are involved as public figures, who travel, teach, try to shape public opinion, whether we are social activists or armchair pundits. It is an issue I fretted about years ago during the height of the cold war, and still do to some extent. The issue is how to stay (for lack of a better word) normal in the face of a pressing historical crisis. Unless one is called to extraordinary sacrifice in these serious times, most of us have kids to play with, gardens to keep, laundry to do. We shop, send facebook updates to friends, we watch movies, we coach Little League, we go to music lessons with our kids (or for ourselves, if we are brave in mid-life.) We have birthday parties and funerals and church and work and important arguments about college football or major league baseball. There are lawns to mow and cars and pets and loved ones to care for.

How does one carry the weight of the world – from the horrors of sexual trafficking to the data about race and mass incarcerations, say, to our outrage about the evils done by other superpowers, or the awareness of species extinction and the likelihood of harsher weather coming and higher prices for food in years to come – and still live with joy? You know the Bruce Cockburn lyric, “the trouble with normal is it always gets worse”? How does one not go crazy or grow weary in a world likes ours where things often do get worse?

Of course, the most foundational answer is spiritual; my friend Tyler Wigg-Stevenson wrote the most important book on this matter for social activists (or anyone who cares and grieves much about the world) entitled, importantly, The World is Not Ours To Save: Finding the Freedom to Do Good. Ruth Haley Barton has a very helpful book for ministry leaders facing burn out and compassion fatigue called Restoring the Soul of Your Leadership, and Peter Greer (of the micro-financing organization, Hope International) has a helpful study, now out in paperback, called The Spiritual Danger of Doing Good which is admirable. Of course, Richard Rohr has several books on the inter-relationship between contemplation and activism — an older one (A Lever and a Place to Stand) was just recently re-issued as Dancing Standing Still: Healing the World from a Place of Prayer. We stock books from Orthodox peacemaker Jim Forest, and his old friend Thomas Merton, to Presbyterian pastor Howard Fiend, Jr. and Quaker Parker Palmer, to contemporary evangelicals like Margaret Feinberg and Shauna Niequist, we are invited to not grow weary, to see God’s hand in ordinary daily life, to experience the Divine in ways that bring wonder and awe and keep us attentive. I think of one of the most helpful books of this sort that I read last year, Luminous: Living in the Presence and Power of Jesus, by David Beck who brings together the purposes, presence, power, and peace of the Holy Spirit as we put ourselves at God’s disposal.

wrote the most important book on this matter for social activists (or anyone who cares and grieves much about the world) entitled, importantly, The World is Not Ours To Save: Finding the Freedom to Do Good. Ruth Haley Barton has a very helpful book for ministry leaders facing burn out and compassion fatigue called Restoring the Soul of Your Leadership, and Peter Greer (of the micro-financing organization, Hope International) has a helpful study, now out in paperback, called The Spiritual Danger of Doing Good which is admirable. Of course, Richard Rohr has several books on the inter-relationship between contemplation and activism — an older one (A Lever and a Place to Stand) was just recently re-issued as Dancing Standing Still: Healing the World from a Place of Prayer. We stock books from Orthodox peacemaker Jim Forest, and his old friend Thomas Merton, to Presbyterian pastor Howard Fiend, Jr. and Quaker Parker Palmer, to contemporary evangelicals like Margaret Feinberg and Shauna Niequist, we are invited to not grow weary, to see God’s hand in ordinary daily life, to experience the Divine in ways that bring wonder and awe and keep us attentive. I think of one of the most helpful books of this sort that I read last year, Luminous: Living in the Presence and Power of Jesus, by David Beck who brings together the purposes, presence, power, and peace of the Holy Spirit as we put ourselves at God’s disposal.

Bill McKibben believes many of these things, I am sure. But the other part of the new book – the “honey part” of Oil and Honey – reminds us of another way to bring a sense of normalcy to our lives (hang in here with me, now.) Believe it or not, this other part of the book isn’t about prayer or meditation or reading good literature. It is a story about beekeeping.

PRACTICES AND PLACE

Yep, to stay grounded amidst lives of missional service or social action or vocational obsessions or passionate advocacy, we need daily practices that somehow keep us involved in local habits, in regional economics, in sustainable living within our own places. You surely know Wendell Berry on this. Scott Russell Sanders has made a beautiful career out of writing well about place (see the excellent anthology of his called Earth Works: Selected Essays.) Many contemporary theological writers and scholars – you can insert Jamie Smith’s name here, now – have insisted that our faith be embodied, incarnational, lived out in concrete practices and not abstract ideals. As I often suggest, the demanding Beyond Homelessness: Christian Faith in an Age of Displacement by Brian Walsh and Steven Bouma-Prediger is a must-read on this. How we live locally as home-makers matters, perhaps more than we know. And Bill McKibben knows this wonderfully and his writing about Vermont is very, very nice.

often suggest, the demanding Beyond Homelessness: Christian Faith in an Age of Displacement by Brian Walsh and Steven Bouma-Prediger is a must-read on this. How we live locally as home-makers matters, perhaps more than we know. And Bill McKibben knows this wonderfully and his writing about Vermont is very, very nice.

You know the old saw “be the change you want to see in the world.” This saying calls us to live lives of integrity, to have some movement towards consistency, integrity, to actually practice what we preach. In a subtle way, that’s part of what this book is about. McKibben seems not to be the sort of guy who is a born national leader, not an out-and-about kind of guy who loves travel and living large. He believes in local and sustainable agriculture, after all. He writes about “helping the neighbors in the sugar bush all afternoon, hauling sap and watching it boil” after “skiing in the woods for a couple of hours.” With his dog, no less. He’s clearly no ambitious, big-time politician.

So it was no surprise (but still good to hear) that McKibben’s struggled with the sanity of flying all over the world, guzzling gas, eating mass-produced morning meals from breakfast bars at discount hotel chains, this life he took up traveling to lead 350.org. And yet, even though he realizes the significance of this big move to organize a movement – it is way past the time for doing more than changing light bulbs, as he puts it – he still loves his local mountains, is greatly informed by his sense of place, the texture of a life lived modestly. He admits how he missed his family, neighbors, (even the ones “the next valley over”) and his beloved, mostly rural state, and he writes about it poignantly. It was telling and very rewarding to read of Bill’s own longings, his emotional sacrifices, his sense of the tensions, living, as he was, through a season of extreme travel, crazy schedules, serious disconnection and perhaps even hypocrisy, given his convictions about localism. But, through-out he tried to keep a connection to in his home places. (One of the more moving portions of the book was his telling of good neighborliness as people mucked out one another’s homes and businesses after the devastation of Hurricane Irene in 2011, right after their DC civil disobedience campaign concluded.)

BEES

W hich takes us to his friendship with one Kirk Webster, the good neighbor and beekeeper who is a main character in the book. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed these parts. McKibben tells of apiaries and bee trays and queen bees and honey markets with simple, clear prose that somehow drew me right in. That he himself is allergic to bee stings and, as he discovered during his stint doing civil disobedience against the XL Pipeline, is not particularly brave, attracted me all the more.

hich takes us to his friendship with one Kirk Webster, the good neighbor and beekeeper who is a main character in the book. I was surprised by how much I enjoyed these parts. McKibben tells of apiaries and bee trays and queen bees and honey markets with simple, clear prose that somehow drew me right in. That he himself is allergic to bee stings and, as he discovered during his stint doing civil disobedience against the XL Pipeline, is not particularly brave, attracted me all the more.

Yes, there is a profound connection between our large public policy matters and the local practices that fuel them. And, as we used to say, the personal is the political. It is increasingly understood that we must stay grounded with friends and family and be involved in local economics of reasonable scale even when we cannot stop our involvement in the fast-paced globalized economy. This helps us take up a posture of being, well, “in but not of” the networks, principalities and powers of secularized globalization. It helps us stay normal.

Who doesn’t realize the particular pleasures and benefits of supporting small, family-owned businesses, artisan coffee roasters, micro-brews, farmer’s markets, the joys of dipping in to real, good honey?

joys of dipping in to real, good honey?

Aaah, I hope you have heard about the evils of how we allow grocers to import Chinese honey that is so poorly regulated that some was stored in barrels that previously stored toxic chemicals! You most likely know that the health benefits of non-local honey is so much less then the amazing benefits of honey from bees who pollinated local fields. This is yet another case study of the brokenness of our industrialized mass agriculture system (selling cheap nutritionally pointless honey imported from far away is costly, dangerous and nutritionally stupid) that has been so well-documented elsewhere.

As you might guess, the portions of Oil and Honey that tell about the bees is less didactic and polemical (even though it surely could have lapsed into a screed, as I nearly did above.) These portions are not a reprieve from the narrative of environmental protests, actually – climate change is a large and looming threat to bees and beekeepers and good honey production – but some of those portions sing with a different sort of joy and tell a very different story then the calls from the White House and the travels to Greenland and the realizations of the dirty tricks of the big oil lobby. Still, the book brings together the global and the local in very striking ways – a literary call and response, perhaps, or a sensible reminder of a two-legged walk? These portions aren’t expose, they are testimony; bee-man Kirk is a local hero, his bees and beekeeping a wonder, and McKibben’s involvement in it (in his timid, over-suited in protective gear, fumbling kind of way) making for a really great read.

And, so, I invite you to read Bill McKibben, and especially to pick up this new, energetic and enjoyable memoir of a year in his life – protesting and learning about bee keeping. You haven’t seen a book like this before, I bet.

Some of this tells of admittedly exotic travels, high-profile, and often dramatic activities (who gets to call a meeting with the White House, get arrested with Wendell Berry, attend parties with a team of entrepreneurial young adults designing websites and using social media to change the world, or talk theology with writers and rock stars?) But some of Oil and Honey: The Education of An Unlikely Activist is very down to Earth (insofar as beekeeping can be down to Earth.) You’ll hear how Kirk built his new barn, Kirk’s intuitions about weather and weeding, and you’ll learn some amazing stuff about bees — I just read a few pages out loud to Beth this evening because it was so amazing! And you’ll hear about how democracy works in rural Vermont, with the town m eetings and all.

eetings and all.

O&H is a great report, exploring two ways of responding to global concerns, two lifestyle choices, in a way – feisty protest or homespun farming. It offers two different examples of being a mentor, leader, the kind of person who leaves a legacy. McKibben with his writing, organizing, and working with emerging leaders in 360.org (and now, the divestment movement in higher education) is obviously mentoring a new generation of grass-roots civic organizers. But so is the stay-at-home agrarian Vermont beekeeper. Mr. Webster, you see, is taking interns, teaching others his innovations in beekeeping, forming the sensibilities and skills of others who will carry on this necessary movement of renewing small-scale farming practices in the 21st century.

And, curiously, if not fully in ways that are completely satisfying, Mr. McKibben brings together these two paths, the political and the personal, his famous public life and his more normal, local life. Indirectly, this is a take-away from the book, what literary types call a sub-text.

How might we, I wonder, in our own callings and careers, citizenship and concerns, live faithfully, “lightly on the Earth” as his earlier book Hope Human and Wild puts it, and nurture lifestyles and practices and ways of being that are helpful, not hurtful, to our world and our neighbors and ourselves? What does it look like to care about “soil and sacraments” (as the title of Fred Bahnson’s wonderful book puts it?) Can churches become more parish-like, witnessing to and joining God’s work in their own place, their own neighborhoods? Can we have big dreams of reforming the social architecture and common life of our culture even while we have some sense of being a faithful presence in our own ordinary homes and neighborhoods?

in our own ordinary homes and neighborhoods?

Read Oil and Honey: The Education of an Unlikely Activist for one man’s extraordinary wisdom, insight, and story doing just this, weaving together the fabric of global politics and local lifestyle. Maybe many of us should be a bit more active in civic life and the politics of the common good. And I suppose we could all learn something from the bees, and appreciate the ways of Kirk the beekeeper. Regardless of where you see yourself in all of this, I think you will enjoy reading it, even if you don’t agree with McKibben’s assumptions or approaches (and even if you are scared of bees.) O&H is a really fine read and would be great to discuss with others.

COMING SOON

Get ready to see my next post coming soon where I’ll list and briefly describe five more books that I believe are essential for those of us wanting serious conversations that explore how to live well in God’s good but hurting world. I promise you that those books are very, very good, inspiring, useful, well-written and important. In the meantime, I’m going to go put a big dash of locally grown honey in a good cup of organic, fairly traded tea, imported from far away. I’m going to drink it with a smile and a hope that this isn’t hypocrisy — importing tea — but steps towards helpful awareness of life as it was meant to be.

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333