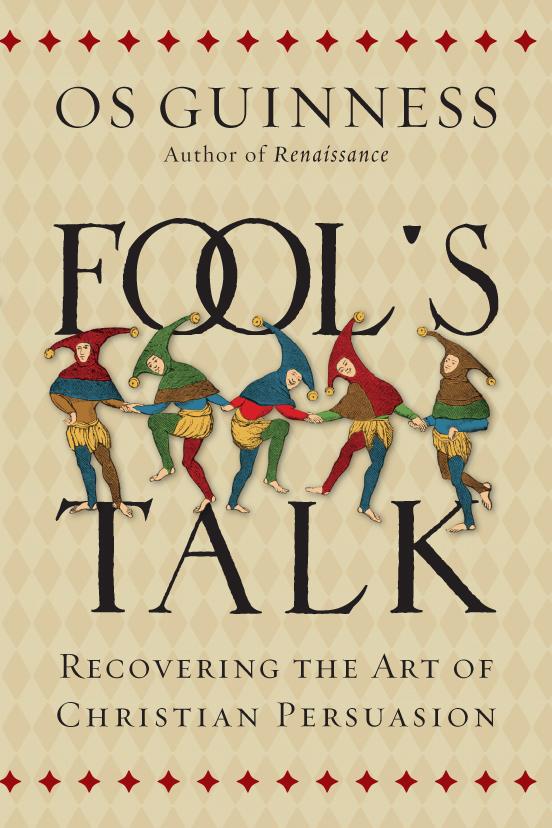

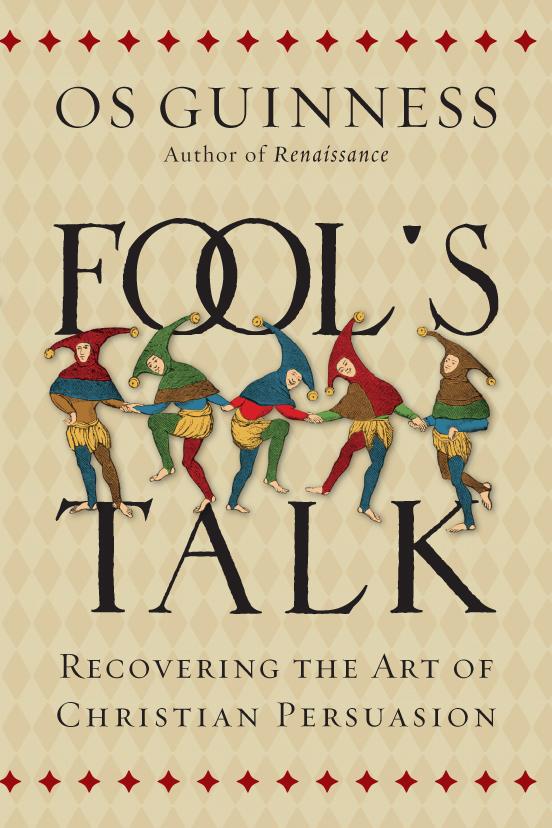

There is little doubt that for many, the new Os Guinness book, Fools Talk: Recovering the Art of Christian Persuasion (InterVarsity Press; $22.00 – our cost, $17.60) is one of the most eagerly anticipated books of the year. Dr. Guinness is one of the most elegant and eloquent speakers and writers I have ever encountered and many esteem him as one of best thinkers and most articulate spokespersons in our generation for informed, thoughtful faith that is Biblical, culturally engaged and, well, persuasive. Guinness’s global experience as a world traveler (he was born in China, lived in Switzerland, studied at Oxford, resides in the US and often participates in global confabs and international symposia) gives him a cosmopolitan air that is sophisticated and attractive and delicious for those of us who value a great communicator with profound material. Most importantly, he is a lucid and compelling advocate for historic, Biblical faith – not fundamentalist, not aligned with the Christian right (or left), not trendy or peculiar or particularly sectarian, but just solid, sensible and faithfully orthodox. He is an ideal personification of what Lewis called “mere Christianity” or what Stott described as “basic Christianity.”

There is little doubt that for many, the new Os Guinness book, Fools Talk: Recovering the Art of Christian Persuasion (InterVarsity Press; $22.00 – our cost, $17.60) is one of the most eagerly anticipated books of the year. Dr. Guinness is one of the most elegant and eloquent speakers and writers I have ever encountered and many esteem him as one of best thinkers and most articulate spokespersons in our generation for informed, thoughtful faith that is Biblical, culturally engaged and, well, persuasive. Guinness’s global experience as a world traveler (he was born in China, lived in Switzerland, studied at Oxford, resides in the US and often participates in global confabs and international symposia) gives him a cosmopolitan air that is sophisticated and attractive and delicious for those of us who value a great communicator with profound material. Most importantly, he is a lucid and compelling advocate for historic, Biblical faith – not fundamentalist, not aligned with the Christian right (or left), not trendy or peculiar or particularly sectarian, but just solid, sensible and faithfully orthodox. He is an ideal personification of what Lewis called “mere Christianity” or what Stott described as “basic Christianity.”

Indian born, Cambridge-educated Ravi Zacharias, another internationally-known, elegant speaker and writer, says “Few thinkers rise to the level that Os does, even as he plumbs the depth of vital issues…”

James Sire says, of this new book,

Fool’s Talk is a direct exposition of the inner logic and rhetoric of persuasion, showing how hearers are moved from unbelief and doubt to conviction of the truth of the Christian faith. Guinness’s focus is not only on the nature of effective argument but the character, ethics and faith of the apologist. Intellectually profound and immensely practical. I loved the book. So will you.

Claremont professor Mary Poplin, whose own journey of faith (by way of Mother Teresa) is wonderfully told in Finding Calcutta and her own cultural assessment is offered in Is Reality Secular? describes the book nicely. She writes,

Os Guinness, in his characteristically clear and insightful style, helps us recover the art of persuasively making the case for the truth of Christianity. Fool’s Talk uniquely suggests we use, not the eager-to-win argumentative styles of the twenty-first century, but the persuasive styles of the church fathers, Old Testament prophets, New Testament writers and Jesus himself as our models. The irresistible nature of their reasoning and Guinness’s brilliance in explaining them is a sure guide for apologists and evangelists, which he wisely urges be one in the same.

To understand the significance of this remarkable work, you should know, too, that Guinness – unlike some who write books about evangelism and apologetics, understands beautifully that the gospel to which we invite seekers and the unchurched, is nothing short of the full-orbed Kingdom of God, the Lordship of Christ lived out in all of life, inspired by the Spirit, shaped by grace, for the sake of the world.

His book 1998 book The Call: Finding and Fulfilling the Central Purpose of Your Life (Word; $17.99) is not only a personal favorite of mine, but has proven to be a watershed book, inspiring a renaissance in discussions about vocation and calling and a faith-based view of work across the Christian community. I routinely cite lines from that great book, drawing on chapters such as “Everyone, Everywhere, in Everything” and “Locked Out and Staying There.”

His book 1998 book The Call: Finding and Fulfilling the Central Purpose of Your Life (Word; $17.99) is not only a personal favorite of mine, but has proven to be a watershed book, inspiring a renaissance in discussions about vocation and calling and a faith-based view of work across the Christian community. I routinely cite lines from that great book, drawing on chapters such as “Everyone, Everywhere, in Everything” and “Locked Out and Staying There.”

It was the one book I chose to review when I was asked to contribute to a book called Beside the Bible (edited by Dan Gibson, John Pattison, Jordan Green; IVP; $15.00) which was a collection of 100 reviews of 100 must-read books — a great book itself, by the way. My own personal debt as a reader to Guinness’s books – including his first, the out of print study of the 1960s counter-culture called The Dust of Death, which I often mention as seminal and life-changing for me – is very significant, even if I do not live up to his impeccable intellectual work or consistent intellectual faithfulness. Further, Os and his lovely wife have been friendly supporters of our bookstore and family, and their prayerful encouragement has been a blessing. I say this so that those who are not familiar with his large body of work or his status as a respected elder statesmen within evangelicalism, would consider buying some of his books. Or at least be inspired to follow along carefully as I describe his work.

Listen to this delightful half hour lecture to see what I mean. Please listen to the end — it is very powerful and you’ll surely appreciate it.

I have greatly admired other, smaller books of Guinness’s like Time for Truth: Living Free in a World of Lies, Hype, and Spin and Prophetic Untimeliness: A Challenge to the Idol of Relevance both which emerge from his serious critique of churches – mostly evangelical ones whose leadership seem to have been largely shaped by managerial models, glamour and an obsession with metrics, thriving on techniques of marketing and light-weight seeker messages rather than conventional church models based on mature worship, robust explication of Scripture, and serious, nonpartisan, social witness. (Although, to be clear, the razor-sharp critique in those books aimed at his fellow evangelicals could equally apply to more liberal churches that embody their own sorts of compromises and idols.)

I have greatly admired other, smaller books of Guinness’s like Time for Truth: Living Free in a World of Lies, Hype, and Spin and Prophetic Untimeliness: A Challenge to the Idol of Relevance both which emerge from his serious critique of churches – mostly evangelical ones whose leadership seem to have been largely shaped by managerial models, glamour and an obsession with metrics, thriving on techniques of marketing and light-weight seeker messages rather than conventional church models based on mature worship, robust explication of Scripture, and serious, nonpartisan, social witness. (Although, to be clear, the razor-sharp critique in those books aimed at his fellow evangelicals could equally apply to more liberal churches that embody their own sorts of compromises and idols.)

His passionate, uplifting book of last year, Renaissance: The Power of the Gospel However Dark the Times (IVP; $16.00) eschews any religious plans to manipulate culture or force social transformation, insisting that even as we work hard to serve the common good, we do so only in God’s ways, relying on Christ alone for cultural renewal, not our political power or social might. (This would be an excellent book to read, by the way, for those who have pondered the Oxford University Press volume To Change the World by James Davison Hunter. Such important and interesting work.)

His passionate, uplifting book of last year, Renaissance: The Power of the Gospel However Dark the Times (IVP; $16.00) eschews any religious plans to manipulate culture or force social transformation, insisting that even as we work hard to serve the common good, we do so only in God’s ways, relying on Christ alone for cultural renewal, not our political power or social might. (This would be an excellent book to read, by the way, for those who have pondered the Oxford University Press volume To Change the World by James Davison Hunter. Such important and interesting work.)

On my short list of titles that are out of print that I long to see reissued is his brief and potent book about developing the Christian mind called Fit Bodies Fat Minds… Again, there, he calls us out for our sloppy thinking and cultural captivity; it seemed to me to be nearly a manifesto for our work as Christian booksellers.

Despite the somewhat negative tone of some of these broadsides, Os has been more than a curmudgeon lamenting churches with feeble visions of vocation or market-driven views of church growth, or postmodern trendiness. His critiques are usually gracious and most always wise, and doubtlessly on the top of my list of books with which thoughtful Christians of any tradition or church affiliation should grapple. I can hardly overstate this, and wish many more readers would take them up and share their insights.

Guinness has given us other sorts of books as well, books sometimes on mainstream/secular publishers, books that bank on his reputation as a former scholar at Brookings Institution, a Senior Fellow of the EastWest Institute in New York, his status as

Guinness has given us other sorts of books as well, books sometimes on mainstream/secular publishers, books that bank on his reputation as a former scholar at Brookings Institution, a Senior Fellow of the EastWest Institute in New York, his status as  a sociologist with a PhD earned under the eminent Peter Berger, media pundit (who did a stint with the BBC), founder of bi-partisan project designed to deepen American’s appreciation for first amendment freedoms, advocating for structural reforms that promote pluralism, religious diversity and which enhance civility. His hard-hitting book Case for Civility was about much more than public manners but offered positive plans for enhancing better public discourse and stability in the public square. His pair of meaty books A Free People’s Suicide and The Global Public Square reflected, respectively, on the threats to religious freedom in North America, and globally. Dr. Guinness has even addressed United Nations diplomats on this topic of religious freedom, inviting them to help “make the world safe for

a sociologist with a PhD earned under the eminent Peter Berger, media pundit (who did a stint with the BBC), founder of bi-partisan project designed to deepen American’s appreciation for first amendment freedoms, advocating for structural reforms that promote pluralism, religious diversity and which enhance civility. His hard-hitting book Case for Civility was about much more than public manners but offered positive plans for enhancing better public discourse and stability in the public square. His pair of meaty books A Free People’s Suicide and The Global Public Square reflected, respectively, on the threats to religious freedom in North America, and globally. Dr. Guinness has even addressed United Nations diplomats on this topic of religious freedom, inviting them to help “make the world safe for  diversity.” A major book, Unspeakable: Facing Up to the Challenge of Evil, attempted to enter the conversation about theodicy, not so much to answer the big question of “why” but to offer a framework for thinking about large evils such as genocide or sexual trafficking. It is a hugely under-utilized book, and I cannot recommend it enough.

diversity.” A major book, Unspeakable: Facing Up to the Challenge of Evil, attempted to enter the conversation about theodicy, not so much to answer the big question of “why” but to offer a framework for thinking about large evils such as genocide or sexual trafficking. It is a hugely under-utilized book, and I cannot recommend it enough.

Fools Talk: Recovering the Art of Christian Persuasion is a book that has been nearly a life-time in the making. Guinness tells us that he made a promise to himself, and to the Lord, that he would not write about evangelism or apologetics (the art of defending the faith and making a persuasive case for the truth claims of the Christian worldview) until he had significant experience doing so. I cannot judge, I really can’t, but I have a sneaking suspicion that some who write  books about evangelism have rarely actually led another to lasting faith and some who write about apologetics like to think about the logic of faith, but, again, may not have had much experience actually befriending skeptics and relating well to those who are hostile to Christian conviction. Although Guinness surely knows the benefit of scholars and thinkers and writers — he cites philosophers and scholarly authors on every page! — he is right that bookish guidance about doing this kind of work simply must be field tested and refined by real conversations, with real people, knowing real failures, sometimes through heartache and tears, even. The topic demands real pages written after years of experience and genuine concern. Guinness writes that he has waited 40 years to write this book.

books about evangelism have rarely actually led another to lasting faith and some who write about apologetics like to think about the logic of faith, but, again, may not have had much experience actually befriending skeptics and relating well to those who are hostile to Christian conviction. Although Guinness surely knows the benefit of scholars and thinkers and writers — he cites philosophers and scholarly authors on every page! — he is right that bookish guidance about doing this kind of work simply must be field tested and refined by real conversations, with real people, knowing real failures, sometimes through heartache and tears, even. The topic demands real pages written after years of experience and genuine concern. Guinness writes that he has waited 40 years to write this book.

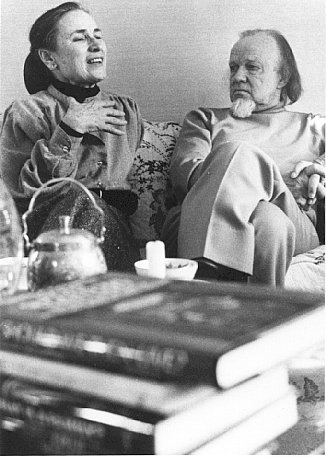

Fools Talk is in a sense everything he learned about the topic from three larger than life influences and mentors: C.S. Lewis, Francis Schaeffer, and Peter Berger (to whom the book is dedicated.)

If this book was Guinness’s guide to either one of these three giants of thoughtful and humane Christian apologetics it would be worth every penny. That he draws on and in some ways brings together all three is remarkable, even extraordinary. I suspect you have not read a book like this, ever.

Guinness, you may know, was on staff at Schaeffer’s L’Abri in Switzerland, and remains a friend of the L’Abri movement. It could be surmised that he may be one of a very small handful of none-family members who knew Schaeffer best. As was mentioned, Guinness earned his PhD at Oxford University in sociology on the esteemed Peter Berger, a renowned sociologist, author, and Lutheran lay leader. Again, he knows the man well.

On occasion Guinness will share an anecdote about one of these three characters, sometimes telling a personal story of his own conversations with them. He writes,

C.S. Lewis, Francis Schaeffer and Peter Berger did not know each other, and they might not even have liked each other, and they might have heartily disagreed with what I have done with their ideas. But the creative clash of their three quite different ways of understanding has set off a nuclear explosion whose energy has fired by thinking. Indeed, I have worked for years in the light of their ideas, and my gratitude to each one of them is unfathomable.

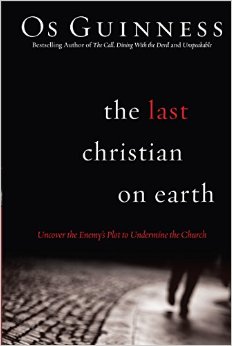

Indeed, he has worked for years in their light. In the early 1980s Guinness tried his hand at a novel, a much-discussed, greatly appreciated story written as a creative set of memos from a spy working for the Enemy (think of a mash-up between John Le Carre and Screwtape) called The Gravedigger Files. This book brought a bit of Lewis, a bit of Schaeffer, and a lot of Peter Berger’s “sociology of knowledge” approach to worldview studies, helping us – via this very creative genre – appreciate the cultural  assumptions in the late modern West and the need of the church to be newly faithful. This was, if I might, the How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor [by James K.A. Smith] of the 1980s, prescient and profound, clever as it was. Looking back, playfully, it could have almost been called “How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Peter Berger.” It was edited, expanded and re-issued in 2010 under the title The Last Christian On Earth: Uncovering the Enemy’s Plot to Undermine the Church (Baker; $17.00.) We found it hard to describe and hard to sell, but it is – I’m not kidding! – a wonderfully thoughtful read, a bit of parable, a bit of cultural exegesis, a playful example of some of what Guinness explores in this new Fools Talk: the need to deeply understand the cultural forces that shape how people think and see and understand and live in this culture, and the need to use humor, satire, and “turning the tables” as a form of apologetics. In Gravedigger cum The Last Christian On Earth Guinness does just that.

assumptions in the late modern West and the need of the church to be newly faithful. This was, if I might, the How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor [by James K.A. Smith] of the 1980s, prescient and profound, clever as it was. Looking back, playfully, it could have almost been called “How (Not) To Be Secular: Reading Peter Berger.” It was edited, expanded and re-issued in 2010 under the title The Last Christian On Earth: Uncovering the Enemy’s Plot to Undermine the Church (Baker; $17.00.) We found it hard to describe and hard to sell, but it is – I’m not kidding! – a wonderfully thoughtful read, a bit of parable, a bit of cultural exegesis, a playful example of some of what Guinness explores in this new Fools Talk: the need to deeply understand the cultural forces that shape how people think and see and understand and live in this culture, and the need to use humor, satire, and “turning the tables” as a form of apologetics. In Gravedigger cum The Last Christian On Earth Guinness does just that.

Which brings us to the very substantial, weighty, examination of the art of persuasion found in this tour de force, Guinness’s 270 page masterwork, inspired by images of the jester, the fool, and what the Apostle Paul called “the foolishness to Greeks.”

In the first few chapters, Guinness is again in his critical mode, exposing the significant failures of apologetics in our day. Even in the introduction he offers an incisive exploration of the impact of digital technologies – many of us, almost subliminally are about self marketing in this age of tweets and selfies – and the doubled-edges of the sword that this is: people are increasingly open and in communication but yet are therefore increasingly wary, weary, even. Who can deny the growing suspicions and cynicism many carry in part due to relentless 24/7 advertising and ubiquitous propaganda? And who can deny that there is much cultural anger against the public face of Christianity, much self-inflicted by the harsher corners of the Christian community? And we all know that there are those who specialize in argument and so-called apologetics but whose loud polemics are simply an embarrassment in contrast to the beauty and grace and richness of the gospel.

Some BookNotes readers will recall our promotion of a book called Slow Church which critiqued the idols of efficiency, technique and speed, and I must say that I thought of that good work by Chris Smith and John Pattison as I followed Guinness’s cultural criticisms. While Smith & Pattison made the case that church should be slowed down, more relational, patient, local, human-scale, Guinness makes parallel recommendations for how we bear witness to the truth of the gospel. We must slow it down, showing more patience, relating well to even our antagonistic conversation partners. We must be aware of the “devil’s bait” of technique and methods, and resist any formulaic, pre-packaged, quick-fix answers. I suspect some of Os’s emphasis on this comes from hanging around

Some BookNotes readers will recall our promotion of a book called Slow Church which critiqued the idols of efficiency, technique and speed, and I must say that I thought of that good work by Chris Smith and John Pattison as I followed Guinness’s cultural criticisms. While Smith & Pattison made the case that church should be slowed down, more relational, patient, local, human-scale, Guinness makes parallel recommendations for how we bear witness to the truth of the gospel. We must slow it down, showing more patience, relating well to even our antagonistic conversation partners. We must be aware of the “devil’s bait” of technique and methods, and resist any formulaic, pre-packaged, quick-fix answers. I suspect some of Os’s emphasis on this comes from hanging around  Francis and Edith Schaeffer who were renowned for the great care and individualized pastoral and apologetic counsel offered in the context of welcoming hospitality that they would give to each and every person they encountered. Guinness is adamant about this and while is seems so obvious that it hardly needs saying, it does need saying. And he says it strongly, even denouncing the “imperialism of technique” and “McTheories.”

Francis and Edith Schaeffer who were renowned for the great care and individualized pastoral and apologetic counsel offered in the context of welcoming hospitality that they would give to each and every person they encountered. Guinness is adamant about this and while is seems so obvious that it hardly needs saying, it does need saying. And he says it strongly, even denouncing the “imperialism of technique” and “McTheories.”

He puts it nicely, saying,

The good news of Jesus is the best news ever, God’s foolishness that is God’s Grand Reversal, which subverts the wisdom of the world to show true wisdom and display real power. Recovering the lost art of persuasion is urgent, timely, and supremely practical, but it is always an art and not a science, and it is not for cheap sales-people but for genuine lovers of Jesus and lovers of truth, beauty, and a knowledge that is more than facts and information.

Way too many training sessions and books and workshops and manuals are provided – for those who even care enough to do such things these days – offering pat answers and tricky strategies for answering the expected questions that people have. Guinness will have none of it, insisting that our friendships with seekers and skeptics must be honest, real, true, and that our replies to their views must be unique, thought-through, and always appropriate for the uniqueness of that particular person and his or her needs, issues, questions, at whatever stage they are on in their spiritual journey.

(An aside, which is more than as aside, I guess, as Guinness mentions it: there are those who no longer care about apologetics at all, and this is regrettable. Some seem to think there is something magically powerful about sheer proclamation, and do not emphasize explanation or argument; others have long come to disdain apologetics because they don’t even think it is important to do evangelism. Sad but true. How glad I was, by the way, that at our local PC-USA Presbytery meeting this week there was a workshop on evangelism!)

Consequently, many of the chapters of Fools Talk are about helping us learn the art of what might be called, in this context, spiritual discernment. (I do not recall that Os uses that phrase, actually, but he advises us to size up the situation and gives us pointers for discerning the stage a person may be on in her journey.) Guinness invites to listen well, to ascertain the deepest issues driving the seeker, and learning the art of attending and responding well to these matters.

To help us, Guinness does some heavy lifting for us, reminding us of Biblical stories and explicit teaching about the duplicitous deviousness of the human heart. We surely must know that, apart from God, many are, frankly, not seekers. People are spiritually dubious, tentative at best. Folks hold presuppositions and idols and false hopes. (Lewis cleverly joked about his own religious disinterest as the absurdity of the “mouse stalking the cat.”) Therefore, we must help people deconstruct their own  deconstructions (one complex chapter is called “turning the tables”) and with wit and kindness but sometimes also hard words spoken well, help skeptics doubt their doubts. (Timothy Keller writes about this clearly in his important and useful Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism.) Guinness uses examples from Lewis, Schaeffer and Berger about doing just this — it is thoughtful, provocative, and finally practical. I love, for instance, his guidance about moving our discernment about the journey of our conversation partners from a meeting point to a pressure point to a danger point, where they are inevitably forced to wrestle with deep things about their deepest convictions and concerns, and realize the consequences of their ideas and beliefs, or lack thereof.

deconstructions (one complex chapter is called “turning the tables”) and with wit and kindness but sometimes also hard words spoken well, help skeptics doubt their doubts. (Timothy Keller writes about this clearly in his important and useful Reason for God: Belief in an Age of Skepticism.) Guinness uses examples from Lewis, Schaeffer and Berger about doing just this — it is thoughtful, provocative, and finally practical. I love, for instance, his guidance about moving our discernment about the journey of our conversation partners from a meeting point to a pressure point to a danger point, where they are inevitably forced to wrestle with deep things about their deepest convictions and concerns, and realize the consequences of their ideas and beliefs, or lack thereof.

The Bible study Guinness does here is curiously intriguing. He draws some important truths from stories – including some that may be lesser known. (Occasionally I thought this was a bit tedious, and then – bam! – he’d offer a line of insight or a take-away point that I had not seen coming, or that I had never considered.) Not only does he draw on great Bible stories but he tells great stories from history. In one section he may tell of a Greek battle or pivotal moment in the Roman Empire and documents the character formation or self-awareness of the ancient leaders and then he will recount the remarkable Christian conversions of serious thinkers such as W.H. Auden or Pascal; on another page he will bring us into an illuminating episode of existential dilemmas from novels like The Plague or the literary reflections of Kierkegaard or Dostoevsky. Or, he will tell about his own long journey home.

Guinness knows the best literature and writings of some of the smartest people in the Western world. I do not want to scare you away, but he cites episodes from the profound reflections of some of the most remarkable thinkers — often to illustrate why great thinkers have rejected the faith, and even if this is slow going for some readers, it is valuable, and you will be rewarded.

Questions are important to Guinness and he commends to us the art and science of asking good questions, questions that are “spring loaded” with other questions.

The human heart and mind must be approached wholistically, so doing proper apologetics is – and this is central to the book – not only about logic and reasons and evidences. Truth is known deeply, in ways that are more than merely intellectual, and we appeal to people with their deepest heart-level questions and fears and issues. Thinkers must think well, but even thinking well is more than a matter of the brain.

(

( You may know how Steve Garber has ruminated on this, first in his significant Fabric of Faithfulness and again in the exceptional and profound Visions of Vocation; or how philosopher Esther Meeks has appropriated the work of Nobel Prize winning scientist Michael Polanyi in her Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People or her Little Manuel of Knowing or her massive Loving to Know: Covenantal Epistemology. Guinness does not reference Garber or Meeks, but he might have.)

You may know how Steve Garber has ruminated on this, first in his significant Fabric of Faithfulness and again in the exceptional and profound Visions of Vocation; or how philosopher Esther Meeks has appropriated the work of Nobel Prize winning scientist Michael Polanyi in her Longing to Know: The Philosophy of Knowledge for Ordinary People or her Little Manuel of Knowing or her massive Loving to Know: Covenantal Epistemology. Guinness does not reference Garber or Meeks, but he might have.)

He even suggests that many moderns have been educated in only the data-oriented left brain, and miss imagination, nuance, analogy, creativity and the like. So our persuasion dare not be reduced to winning intellectual arguments or merely refuting the claims of the atheists.

Guinness knows all this very well, and helps us appreciate the complexity of the apologetic task by quoting or retelling writers, artists, or philosophers who have penned their memoirs or philosophical reflections about their own rejection of faith, their own sense of knowing what they know, and what they came to trust or not trust. We must understand how the human soul works, and listening in on the likes of Arthur Koestler or Schopenhauer or Nietzsche or Jung or Irtega y Gasset or Ronald Dworkin helps us, especially as Guinness gives us background and uses their quotes so effectively. Guinness has done the heavy lifting for us, bringing us these reports from the greatest minds that have written about these things, and we would do well to ponder them carefully. His framing them, explaining what we can learn from the nature of their unbelief is nothing short of brilliant.

Of course, he tells more than the useful stories that expose the anatomy of unbelief. He examines the thoughtful conversion narratives of great writes such as Augustine – you really have to know more of his story! – and C.E.M. Joad and Chesterton and Pascal and, of course, C.S. Lewis. Whether you know these names or not, it is good, intriguing storytelling, offering great, witty lines.

Allow me to say this, however: you may, like me, regret that most of these citations and stories are from great intellectuals of the West, and the novels and plays he cites are decades old, at best. I do not know if today’s thinkers – young or old – care much about Plato or Milton, Yeats or Kafka, Ibsen or even Iris Murdoch or Agatha Christy. I wish Os would cite contemporary films or more recent scholars or at least a few contemporary lyrics from indie rock artists or a stand up comedian or TV drama. I know that Dorothy Sayers and her once-popular mysteries provide great illustrations and certainly most of us need schooled in the writings of Erasmus and Chesterton, say, but it is nearly ironic that in a book so insightful about attending to one’s conversation partner, being a good listener and aware of the audience and her social location and cultural context, Guinness (and his editors?) seem unwilling to offer on-ramps to these significant, older authors. (Don’t you hate it when an author says somebody “famously” says something and it is a person you’ve never heard of, saying something you’ve never heard of?) Again, it is not bad that Guinness cites Lucretius rather than Ludicrous (your welcome for that wordplay there) or Alberto Giacometti rather than Paul Giamatti (again, your welcome) but it might have been a more reader-friendly book if only…

Another major section of Fool’s Talk comes in chapters that warn about the dangers of our own foibles, and the huge challenges they create in the minds of the unchurched, obstacle for our Christian advocacy. Useful, must-read books like UnChristian (Gabe Lyons & David Kinnaman), You Lost Me (David Kinnaman) or James Emery White’s The Rise of the Nones are excellent entries to these concerns, but Guinness, naturally, brings a deeper understanding and more profound response.

Another major section of Fool’s Talk comes in chapters that warn about the dangers of our own foibles, and the huge challenges they create in the minds of the unchurched, obstacle for our Christian advocacy. Useful, must-read books like UnChristian (Gabe Lyons & David Kinnaman), You Lost Me (David Kinnaman) or James Emery White’s The Rise of the Nones are excellent entries to these concerns, but Guinness, naturally, brings a deeper understanding and more profound response.

For instance, in a chapter on hypocrisy (“Beware the Boomerang”) he offers six steps to pursue in responding to charges of hypocrisy; this is truly valuable since such accusations are common and, frankly, a legitimate critique of Christian faith — but it is not simplistic. It is rich, good stuff. Similarly, in a chapter called “The Art of Always Being Right?” Guinness explains the dangers of arrogance and pride and too much confidence in dogmatic, pat answers. His approving citation of Albert Camus’ brave intent, “To tell the truth without ceasing to be generous” is a good reminder. His call to “gentleness ” and “respect” (see I Peter 3:15) is lovely, and his quoting St Augustine who was “honest facing up to the temptation of using words as power” is fabulous. His stuff about asking good questions is brilliant.

Guinness observes, “…all too often the urge to win and to win at all costs breaks through in Christian speech, whether in showy exhibitionist rhetoric or ruthless steamrollering.” Ain’t that so true?

He lifts up famous Christians who showed a better way, from ancients like Gregory of Nazianzus and Ambrose to Chesterton’s decency in his famous debates with George Bernard Shaw, to the (contemporary) “humility and humor of Professor John Lennox of Oxford University in his recent debates with new atheists.” Nice!

Again – to underscore the point of this book which is a guide to learning how to persuade, not just scold or proclaim or badger or win arguments about religion – Guinness in this chapter explores some of the parables of Jesus and how they were so remarkably able to unsettle and expose and invite the hearers to repentance and a realization of grace. He worries that in all our efforts to win debates (at least those of us who enter into religious conversations, having perhaps read books on how to argue well) we sometimes make a winning argument, taking the battle, so to speak, but losing the war, as it were. The goal of our conversations, he repeats, is not to win debates or look good in our sophisticated arguments, but to touch lives, inviting people to faith through grace. We want people to care about truth so they might come to trust the God who loves them so. He writes,

The false art of always being right is a deadly trap for Christian advocates. Conversely, it is a high privilege to use the art of persuasion to bring people to where they know in their heart of hearts that they are wrong, that God’s offer of grace is free. Little wonder that such a privilege and such an art can only be pursued with humility and with an overwhelming sense of God’s grace to us, too. Again, the art of truth leads back to the incarnation, the cross and the Holy Spirit, and the life of faith continues as it began.

This reminder is the theme of the beautiful Epilogue, called “The Way of the Open Hand.” He explains that this symbol points us to

the positive side of apologetics that uses the highest strengths of human creativity in defense of truth. Expressing the love and compassion of Jesus, and using eloquence, creativity, imagination, humor and irony, open-hand apologetics has the task of helping pry open hearts and minds that, for a thousand reasons, have long grown resistant to God’s great grace…

You will notice, in this good quote from the last page, that Os mentions the imagination, humor and irony. These are actually explored in great detail – rather humorlessly, I might note – as Guinness teaches us from Peter Berger, who wrote (in the 1960s) profound work on what we might call the sociology and spirituality of humor. The chapter called “spring loaded dynamics” is perhaps the most challenging in the book and yet may be the most important. Here, Guinness’s debt to Berger and Schaeffer and Lewis are evident, and it is nothing short of brilliant. Yet, dense and brilliant as it is, it must be read in light of a previous chapter – one that has Berger’s fingerprints all over it – called “Triggering the Signals.”

You may have heard the phrase (coined by Berger, I gather) “signals of transcendence.” Lewis himself explained how this reality was key in his own conversion (“surprised by joy”) and Os develops it clearly.

Shifting from Lewis to Berger, he writes,

Berger’s rich discussion of other signals of transcendence are a goldmine for the Christian advocate. It covers such typical human experiences as hope, play, humor, order, and judgement. His discussion is fresh and invigorating, but we should see it as a brilliant rediscovery rather than as radically new, for this was a powerful theme in the early church. In the third century, for example, Gregory of Nyssa built on the Greek notion of desire and developed it in a biblical direction.

Guinness is fantastic here, swiftly reminding us of Gregory’s profound teaching, shifting to Augustine, noting that “the same understanding of desire blazes in St Augustine, fanned by his own experience of passionately searching for God” and then on to, for instance, the telling of the story of Le Chambon (the famous town in France that hid Jews from Nazism’s reach) and how author Philip Hallie (Lest Innocent Blood Be Shed) was drawn to “how goodness happened there.”

Of course, when a seeker realizes that there must be some Giver if there are gifts, some Signaler if there are signals, some Meaning-giver if there is any meaning, he or she can still say “yes,” “no” or “not  yet” to the invitation to understand that Meaning-giver as the God of the Bible, incarnate in Jesus the Christ. People may “fall on their knees or turn on their heels.” Like in his wonderfully rich book for seekers called The Long Journey Home: A Guide to Your Search for the Meaning of Life (WaterBrook; $18.99) Guinness helps us chart the journey of our conversation partners, helping them do some ruthlessly honest self appraisal, realizing that signals of transcendence may not immediately draw skeptics to faith. (That is why we need “spring loaded” dynamics, asking probing questions, and the tools of wit and irony and even the ploys of good drama to push and pull our friends to deeper questions and new plausibilities and finally new answers.)

yet” to the invitation to understand that Meaning-giver as the God of the Bible, incarnate in Jesus the Christ. People may “fall on their knees or turn on their heels.” Like in his wonderfully rich book for seekers called The Long Journey Home: A Guide to Your Search for the Meaning of Life (WaterBrook; $18.99) Guinness helps us chart the journey of our conversation partners, helping them do some ruthlessly honest self appraisal, realizing that signals of transcendence may not immediately draw skeptics to faith. (That is why we need “spring loaded” dynamics, asking probing questions, and the tools of wit and irony and even the ploys of good drama to push and pull our friends to deeper questions and new plausibilities and finally new answers.)

You see, all of this is complex and serious, demanding that we unlearn and relearn how to persuade, not just win arguments or, worse, meanly moan about the atheists and unchurched and nones. We need fresh, thoughtful evangelism, and that will mean learning this discerning art and taking up with fresh energy the call to be persuasive. Of course we only do this in concert with the Holy Spirit of God, whose job it is to call and convert and transform. Yet, we have our part to play.

And here is a large point: we may seem like fools to the watching world to press hard to give a fulsome witness to faith – no matter how creatively and winsomely and passionately we argue. Are we willing to seem like “fools for Christ?”

And is there some sense in which our foolishness is just what is needed?

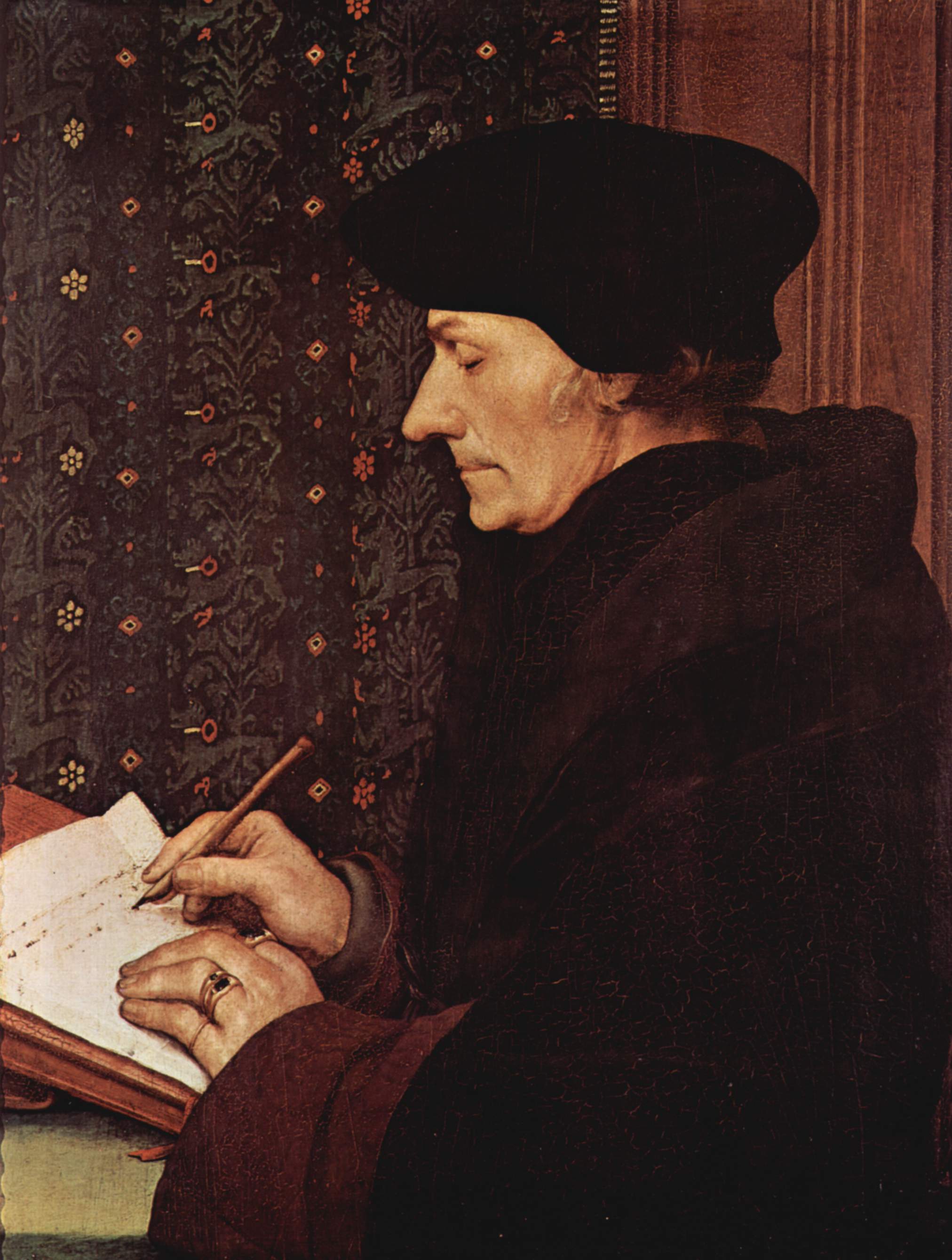

Guinness thinks that is exactly right and he has talked about this often in older lectures and has hinted at it in more than one book. His chapter “The Way of the Third Fool” that clarifies what he means by being a fool, based on his astute reading of the notion of foolishness in the Bible, is very important, and I don’t think I’ve seen anything like it anywhere. You will have to ponder it a bit, but it is quite intriguing. Just for instance, at one point, he draws on the notion of a book by Desiderius Erasmus, published in Rotterdam in the early 1500s called The Praise of Folly.

Guinness thinks that is exactly right and he has talked about this often in older lectures and has hinted at it in more than one book. His chapter “The Way of the Third Fool” that clarifies what he means by being a fool, based on his astute reading of the notion of foolishness in the Bible, is very important, and I don’t think I’ve seen anything like it anywhere. You will have to ponder it a bit, but it is quite intriguing. Just for instance, at one point, he draws on the notion of a book by Desiderius Erasmus, published in Rotterdam in the early 1500s called The Praise of Folly.

This is tricky business, though, and we need Guinness’s good guidance to get it right, I think. Of Erasmus’s satirical project, he writes,

Needless to say, not everyone understood Erasmus’s point. On the one hand, some people failed to understand his fool-making style and interpreted him woodenly. One stolid reviewer, a fellow cleric, wrote that now that Erasmus had written his brilliant book The Praise of Folly, he should consider writing a second book, The Praise of Wisdom. Poor man. Earnest, wooden and literalistic, he had missed the point. Erasmus had written The Praise of Wisdom but he had written it upside down and inside out in order to be more persuasive to those who were resistant to being challenged.

One of the things I appreciate about Fools Talk is how Guinness himself sometimes helps us from misunderstanding. In a section talking about the use of the arts to help us in this process of “turning the tables” and offering “spring loaded” questions, he tells of an artist who objected, wondering if this intentional nuancefulness was demeaning the arts themselves, recruiting them for some subversive task that had this apologetic goal. Os’s response, although brief, is clear and helpful. Throughout, just when things are piling up, quotes and ideas and points and theological polemics, he offers a story, an example, often from his own life. From conversing with atheist philosopher A.J. Ayer during a train ride to his own experience pondering life’s meaning when a possible brain tumor threatened his well being, Guinness brings this all home. He is a scholar and learned writer, but he is not a dry intellectual. I learned years ago that he does not view that epithet as a compliment.

One of the things I appreciate about Fools Talk is how Guinness himself sometimes helps us from misunderstanding. In a section talking about the use of the arts to help us in this process of “turning the tables” and offering “spring loaded” questions, he tells of an artist who objected, wondering if this intentional nuancefulness was demeaning the arts themselves, recruiting them for some subversive task that had this apologetic goal. Os’s response, although brief, is clear and helpful. Throughout, just when things are piling up, quotes and ideas and points and theological polemics, he offers a story, an example, often from his own life. From conversing with atheist philosopher A.J. Ayer during a train ride to his own experience pondering life’s meaning when a possible brain tumor threatened his well being, Guinness brings this all home. He is a scholar and learned writer, but he is not a dry intellectual. I learned years ago that he does not view that epithet as a compliment.

Well. Readers can tell this work comes from a life time of thinking and doing.

The wait was worth it.

This is a book that combines great learning, passion for God’s glory and Biblical truth, and a great array of experience with life, with friendships, with conversations with world-class thought leaders as well as with ordinary people, from militant atheists to disillusioned church goers, older and younger, well-educated and less so. The writing is not simplistic, as this is no simple matter. Lives are at stake and while the destiny of each soul and the health of our post-Christian culture finally is in the hands of the God of heaven and Earth — remember his previous book Renaissance — we have to be attentive to serious matters in these serious times. Dr. Guinness has thought hard, read widely, listened well, and is always the teacher, inviting us to consider things not only in a new light, but in a deeper hue. I respect his work, and commend it to you. I especially recommend this brand new Fools Take: Recovering the Art of Christian Persuasion.

***

So here I am, trying my best to describe this book, to pique your interest, but, perhaps I am not being persuasive. What an irony!! Please, please, forgive me for my lack of clarity or for not making this sound compelling. I invite you to ponder your own needs and interests, and invite you to work through this book, perhaps with another. I think it will be illuminating, helpful, and, for some, even if you may not agree with every bit, it will be a paradigm-shifting, transforming experience.

So here I am, trying my best to describe this book, to pique your interest, but, perhaps I am not being persuasive. What an irony!! Please, please, forgive me for my lack of clarity or for not making this sound compelling. I invite you to ponder your own needs and interests, and invite you to work through this book, perhaps with another. I think it will be illuminating, helpful, and, for some, even if you may not agree with every bit, it will be a paradigm-shifting, transforming experience.

Fools Talk is, in the words of Jerry Root (himself a Lewis scholar) “necessary and vitally important.”

Michael Ramsden of the Oxford Centre for Christian Apologetics says it is “a remarkable book… I whole-heartedly recommend it.”

Or, if I may dare marshal evidence, our friend and professor of these very topics, William Edgar, writes, interestingly,

There is no doubt about it, Christian apologetics is having a renaissance. Oddly though, precious little of it addresses the art of persuasion. Who better to redress this lacuna than the preeminent apologist of our times, Os Guinness. Among the many virtues of Fool’s Talk is the presentation of a robust Christian faith that is not predictable. Many people are so sure they know what Christians are going to say that they don’t actually listen. Guinness keeps them off-balance, much in the way Jesus’ parables caught his audiences off-guard. Faced with a plethora of modern challenges, from technology to globalization to political sales talk to moral relativism, we are tempted to develop a single, safe, reactionary method–ten steps to the punch line. Guinness does the opposite. Like G. K. Chesterton in an earlier age, Guinness reminds us that truth is quite unlikely, that is, dubious to unaided reason. He advocates a broad range of arguments, all of them imaginative, but all of them pointing to the surprising truth, the unpredictable love of God.”

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333