The new book by my friend Jamie Smith has arrived, and we couldn’t be happier. The endorsements on the cover of the nice hardback are stellar. It is doubtlessly one of the best books of the year. Read on.

The new book by my friend Jamie Smith has arrived, and we couldn’t be happier. The endorsements on the cover of the nice hardback are stellar. It is doubtlessly one of the best books of the year. Read on.

Please notice the handy order link at the bottom of this BookNotes column that takes you to our certified secure order form page. We hope you value the reviews we offer and we trust that if you want to buy the books you will send the order our way. Thank you, warmly.

I hope you enjoyed my long essay about what I called the backstory of James K.A. Smith’s spectacular new book, You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit, that we offered in a BookNotes post a week ago. I named authors who have been significant for me, that influenced us to open Hearts & Minds, and for the development of the CCO’s Jubilee conference I talk so much about. Some of these, in fact, were also significant influences, friends, conversation partners, and teachers of James K.A. Smith. Every one of the books I mentioned is important to his project and I hope you paid attention.

That long rumination mostly went like this: influenced by Dutch neo-Calvinists — old-time theologians and civic leaders like Herman Bavinck, Abraham Kuyper and serious philosophers like Herman Dooyeweerd (and, to a lesser extent, Francis Schaeffer) — The Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto influenced in the 1970s both Reformed and evangelical folks, including some of us in Pittsburgh who caught their “wide as life” vision of redemption, that understood salvation as “creation regained” and challenged the church’s anti-intellectualism and cultural

That long rumination mostly went like this: influenced by Dutch neo-Calvinists — old-time theologians and civic leaders like Herman Bavinck, Abraham Kuyper and serious philosophers like Herman Dooyeweerd (and, to a lesser extent, Francis Schaeffer) — The Institute for Christian Studies in Toronto influenced in the 1970s both Reformed and evangelical folks, including some of us in Pittsburgh who caught their “wide as life” vision of redemption, that understood salvation as “creation regained” and challenged the church’s anti-intellectualism and cultural  laziness. This shifted the tone of our faith conversations and our understanding of discipleship towards a more culturally engaged and wholistic vision, a transforming vision. We started using the phrase world-and-life-view, shortened it to worldview and regularly explained how bad ideas (like the pagan Greek notion adopted from Plato by the early church of a big divide between the so-called secular and sacred and the subsequent general disregard for culture, work, the arts and sciences) could deform our discipleship and harm our witness in the world. 3D glasses picture from FEVA Ministries

laziness. This shifted the tone of our faith conversations and our understanding of discipleship towards a more culturally engaged and wholistic vision, a transforming vision. We started using the phrase world-and-life-view, shortened it to worldview and regularly explained how bad ideas (like the pagan Greek notion adopted from Plato by the early church of a big divide between the so-called secular and sacred and the subsequent general disregard for culture, work, the arts and sciences) could deform our discipleship and harm our witness in the world. 3D glasses picture from FEVA Ministries

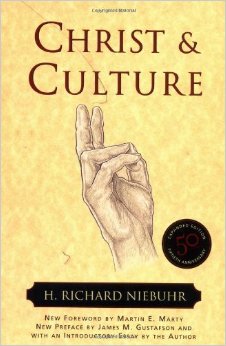

We resonated with the critique offer by Richard Neibuhr in his classic Christ and Culture and we

ran with that taxonomy – dualists of the right were fundamentalists who despised culture; their faith often opposed Christian social concern, while more liberal dualists accommodated themselves to culture; the Reformed “Christ transforming culture” option gave us the most helpful posture: in but not of the world, eager to make a difference with holy relevance. As a book by Richard Mouw put it in those years we were “called to holy worldliness” and as another by Robert Webber put it we were to be “secular saints.” Some of my very best friends in the CCO wrote a book (now long out of print) called, simply, All of Life Redeemed.

ran with that taxonomy – dualists of the right were fundamentalists who despised culture; their faith often opposed Christian social concern, while more liberal dualists accommodated themselves to culture; the Reformed “Christ transforming culture” option gave us the most helpful posture: in but not of the world, eager to make a difference with holy relevance. As a book by Richard Mouw put it in those years we were “called to holy worldliness” and as another by Robert Webber put it we were to be “secular saints.” Some of my very best friends in the CCO wrote a book (now long out of print) called, simply, All of Life Redeemed.

THE WORD WORLDVIEW

Alas – and it is a lot more complicated than I am putting it here, and more complicated than I described in that BookNotes – other folks started using the word worldview, too, sometimes hitching it to a far-right (dominionist) agenda, and usually using it to merely categorize the wrong ideas of others about the nature of the world. The notion of a worldview was in some places reduced to mere ideas – good ones or bad ones – and some seemed to think that if we could only get people to believe the better ideas (dualism is wrong, God loves the creation, humans are made as God’s image-bearers so we are called to vocations and work and history-making, Christ is Lord of all of life, Christians are to denounce the idols of the culture, the Kingdom of God is more than just the gathered church on Sundays) then they would be able to become true agents of God’s Kingdom, culture-makers, ambassadors, restorers. God’s Kingdom could come if we just thought harder and better, usually by reading the right books and got our “worldview glasses” polished up correctly.

(For the record, although beyond the scope of my overview of and run-up to Smith’s new book, I think this telling is somewhat overstated. Some odd-ball right-wing dominionists and some interested in evidentialist apologetics started using worldview language, but many who used it – from James Sire to Nancy Pearcey, Al Wolters to Sylvia Keesmaat, Mark Bertrand to NT Wright – mostly did not reduce the notion of a deeply held, often subconscious heart perspective, shaping how we “lean into life” as Sire put it, to mere ideas. Suggesting this is, in my view, a small mis-step made by Andy Crouch in his splendid Culture Making and it is a trope in Smith (especially in Desiring the Kingdom) that ought to be clarified somewhere along the line. In recent years, James Sire attempted to clarify the notion of worldview as a concept in a book called Naming the Elephant, which is worth reading. I’ve already cited in that previous BookNotes the collection about all this called After Worldview published by Dordt College Press. In any event, there is a huge difference between, say, James Olthius (and his 1985 Christian Scholars Review article “On Worldviews” citing Clifford Geertz and Michael Polanyi and Kierkegaard and David Tracy) and any number of far-right televangelists who started using the word promiscuously without much understanding of its best usage. But I digress. )

(For the record, although beyond the scope of my overview of and run-up to Smith’s new book, I think this telling is somewhat overstated. Some odd-ball right-wing dominionists and some interested in evidentialist apologetics started using worldview language, but many who used it – from James Sire to Nancy Pearcey, Al Wolters to Sylvia Keesmaat, Mark Bertrand to NT Wright – mostly did not reduce the notion of a deeply held, often subconscious heart perspective, shaping how we “lean into life” as Sire put it, to mere ideas. Suggesting this is, in my view, a small mis-step made by Andy Crouch in his splendid Culture Making and it is a trope in Smith (especially in Desiring the Kingdom) that ought to be clarified somewhere along the line. In recent years, James Sire attempted to clarify the notion of worldview as a concept in a book called Naming the Elephant, which is worth reading. I’ve already cited in that previous BookNotes the collection about all this called After Worldview published by Dordt College Press. In any event, there is a huge difference between, say, James Olthius (and his 1985 Christian Scholars Review article “On Worldviews” citing Clifford Geertz and Michael Polanyi and Kierkegaard and David Tracy) and any number of far-right televangelists who started using the word promiscuously without much understanding of its best usage. But I digress. )

THE POSTMODERN TURN AWAY FROM RATIONALISM

In that BookNotes the other day I not only explained the influence of the Dutch worldviewish authors from ICS that influenced CCO and Jubilee in the 70s and 80s but named a second sort of influence within some of those same circles (my circles, the friends and conversations that shaped the founding of Hearts & Minds.) Call it worldview 2.0 or the second (postmodern) wave. I explained a few reasons why a new way of talking about worldview developed and a few books in which some like Brian Walsh and Jamie Smith made a bit of a postmodern turn and came to realize the limits of overemphasizing the role of thinking, the notion of the Christian mind being developed mostly by depositing new ideas into our brains. (The aforementioned, little-known book published a few years back by Dordt College Press, After Worldview, edited by Matt Bonzo and Michael Stevens, documents the papers presented at a  heavy conference – bracing, contested, important — on this very matter and a whole academic book was edited in 2008 by Neal DeRoo and Brian Lightbody dedicated to Smith’s views, The Logic of Incarnation: James K.A. Smith’s Critique of Postmodern Religion.) Walsh, Midddleton and Smith were not the only ones in evangelicalism to write favorably of postmodernism, but they were pioneering and prescient. They started to write more about the role of the heart and the imaginative stories that conscript us into visions of the good life. Perhaps we should talk more about stories and visions, and less about worldviews and ideas.

heavy conference – bracing, contested, important — on this very matter and a whole academic book was edited in 2008 by Neal DeRoo and Brian Lightbody dedicated to Smith’s views, The Logic of Incarnation: James K.A. Smith’s Critique of Postmodern Religion.) Walsh, Midddleton and Smith were not the only ones in evangelicalism to write favorably of postmodernism, but they were pioneering and prescient. They started to write more about the role of the heart and the imaginative stories that conscript us into visions of the good life. Perhaps we should talk more about stories and visions, and less about worldviews and ideas.

Maybe, as Saint Augustine said, we are not primarily creatures who firstly think, but creatures who primarily love. The decisive question is not so much what we believe, but what we love.

As Smith puts it in the splendid preface to this new book: Jesus asks us “what do you want?”

I wrote that last BookNotes column so you can see, again, a bit of our backstory, our own journey, the ideas and visions that excite me and that inspired Beth and I to start our bookstore nearly 34 years ago. And because I think some of that backstory and naming of titles illumines the great passion and urgency with which James K.A. Smith now writes, seen in books such as his good collections of pointed, shorter essays like The Devil Reads Derrida and Other Essays on the University, the Church, Politics, and the Arts and Discipleship in the Present Tense: Reflections on Faith and Culture, or his deep and exceptionally thoughtful Desiring the Kingdom: Worship, Worldview, and Cultural Formation (2009) and Imagining the Kingdom: How Worship Works (2013), and the brand new, much-anticipated, very accessible You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit.

SO VERY NICELY WRITTEN, A TRUE PLEASURE TO READ

You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit is an amazingly rich book, and it explains Smith’s thesis in many ways, using lots of analogies, illustrations, and teacherly examples. Throughout the book he switches the words around, rephrasing his basic points so often that one is not only learning these new ideas about the role of habits that shape our loves, but we are acquiring new ways to talk about these things, ways to describe our faith, our discipleship, our worldviews, and our worship with language that seem to now carry fuller, richer meaning. He talks about “curating your heart” and “calibrating your desire” and “refining your yearnings.” He drops great little lines, over and over, such as “love is both a habit and hunger.” He notes how liturgies “govern our rhythms” and asserts that “the church is the place where God invites us to renew our loves, reorient our desires, and retrain our appetites.”

You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit is an amazingly rich book, and it explains Smith’s thesis in many ways, using lots of analogies, illustrations, and teacherly examples. Throughout the book he switches the words around, rephrasing his basic points so often that one is not only learning these new ideas about the role of habits that shape our loves, but we are acquiring new ways to talk about these things, ways to describe our faith, our discipleship, our worldviews, and our worship with language that seem to now carry fuller, richer meaning. He talks about “curating your heart” and “calibrating your desire” and “refining your yearnings.” He drops great little lines, over and over, such as “love is both a habit and hunger.” He notes how liturgies “govern our rhythms” and asserts that “the church is the place where God invites us to renew our loves, reorient our desires, and retrain our appetites.”

YAWYL is exceptionally quotable – I have more sentences underlined in my copy than not. I promise you, reading this book — just over 200 pages – you get your money’s worth!

Smith’s writing at times just sparkles, and there are fabulously generative and sensible sentences like this, where he is summarizing some very good pages about the relationship of daily Christian life in the home and the story arc rehearsed in serious Christian worship among the gathered people of God:

When we situate our households in the wider household of God and extend the liturgies of worship to shape the ethos of our homes, we re-situate even the mundane. When we frame our workaday lives by the worship of Christ, then even the quotidian is charged with eternal significance. Our “thin” practices take on thicker significance when nested in a wider web of kingdom-oriented liturgies.

THE BOOK ACTUALLY WORKS — INFORMING THE MIND, ENLARGING THE HEART. YES!

I am not trying to be cute, but I think this book works as an old-school text (we really do learn a lot) but also as an influence of this deeper, formative process – by immersing ourselves in this story, Smith’s winsome, teacherly ways, his pop culture and literary examples, his love for church and worship, his creative use of phrases, his new rhetoric, we are ourselves transformed. Our affections are stirred and our hearts enlarged. We are carried into a better story, inspired to feel differently about church and worship, life and times. This truly is a book for hearts and minds.

Is this itself a contradiction, saying that a book can get to us like this? If Smith is saying that our worldviews, our practices of daily discipleship, our truest desires, are shaped more by rituals of worship and habits that are less didactic and more imaginative, can a non-fiction book about all that be effective and truly transformative? Maybe we need an interactive mime troupe or a play about this, at least, or maybe, if he’s really right, we should just skip the book and attend Episcopal liturgies each day, practicing worship rituals over and over. Ha, that’s part of the seeming irony of this, and a hint that, at times, Smith verges on overstating his insights. Books about big ideas really can be formational and our whole-hearted engagement with them – maybe doing something like lectio divino, processing the content — can be transforming. (Especially if it is read and processed together, in community.) Smith doesn’t disagree, of course, and says so in several clear pages in the first chapter. He is a professor and writer of non-fiction books, after all.

THE FIRST MAJOR PREMISE OF THE BOOK: A GAME-CHANGER

I should like to explain the overview of Professor Smith’s project and describe a bit of how he says what he says. You can be assured that You Are What You Love is a thrilling book to read, substantive and stimulating, but it is not so academically rigorous to be tedious or inaccessible. It is much, much more than an abridged and simplified version of the admittedly complex Imagining the Kingdom and Desiring the Kingdom although I suppose that is one way to describe it: accessible summaries of the gist of those two exceptional works. Educated, ordinary readers will find YAWYL a pleasurable read and will enjoy it with ease; I am sure many will be moved deeply by some of it. I am confident that its inviting, clear style will make it widely used and a game-changer for many.

NOT UNLIKE LEARNING RACISM, NOT UNLIKE SHEDDING ONE’S SKIN

I started my overview in the “Part One” review in last week’s BookNotes by citing a memoir I recently read (highly, highly recommended, as well) written by Jim Grimsley, called How I Shed  My Skin: Unlearning the Racist Lessons of a Southern Childhood. Grimsley grew up in rural North Carolina, one of the students at one of the schools in the late 60s that were the first to become racially integrated. Without excessive flourish Grimsley described how he was born and bred to be a racist, by otherwise good people in his small, religious town. While most frowned on the public usage of the “n-word” (it was considered “course”) and several of the Klansman his parents knew were disrespected for their excessive violence, he, nonetheless, was unknowingly conscripted into a culture of white supremacy. The goal of his captivating memoir was to ponder how he, over time, “shed the skin” with which he was raised. How does one’s heart become taken with bigotry and how does one unlearn such disordered prejudices? Although the book is not heavy-handed, it seemed to me a spot-on parallel to one of Mr. Smith’s central arguments, namely, that we are not primarily or firstly “thinking things” and therefore, “thinking-thingism” (one of the very few clumsy phrases in the book) will not do if we desire to deepen our discipleship and live more consistently Christian lives.

My Skin: Unlearning the Racist Lessons of a Southern Childhood. Grimsley grew up in rural North Carolina, one of the students at one of the schools in the late 60s that were the first to become racially integrated. Without excessive flourish Grimsley described how he was born and bred to be a racist, by otherwise good people in his small, religious town. While most frowned on the public usage of the “n-word” (it was considered “course”) and several of the Klansman his parents knew were disrespected for their excessive violence, he, nonetheless, was unknowingly conscripted into a culture of white supremacy. The goal of his captivating memoir was to ponder how he, over time, “shed the skin” with which he was raised. How does one’s heart become taken with bigotry and how does one unlearn such disordered prejudices? Although the book is not heavy-handed, it seemed to me a spot-on parallel to one of Mr. Smith’s central arguments, namely, that we are not primarily or firstly “thinking things” and therefore, “thinking-thingism” (one of the very few clumsy phrases in the book) will not do if we desire to deepen our discipleship and live more consistently Christian lives.

Bad orientations/views/ ideas/practices (like Mr. Grimsley’s racism) are absorbed and developed and embodied into bad habits largely not by overt or didactic teaching but via bad liturgies – civic rituals that form us and shape us. Such (dis)ordering character (mis)formation must be countered by other sorts of better rituals and more powerful liturgies which embody and cultivate within us other sorts of habits of heart that will, in turn, shape and form our sense of what story we are a part of, re-indexing our desires in more wholesome ways. Character and virtue and life’s orientations are shaped pre-theoretically (a word we learned from ICS in the 70s, mind you), Smith insists, and this is exactly what Grimsley describes in his poignant memoir.

Grimsley tells of reciting children’s playground doggerel, rhymes and rituals to determine who was “it” in a game of tag, that used the n-word — thoughtless, but toxic nonetheless. (Add to this the background wallpaper of overt racism in the Jim Crow south, separate but not equal, and one can easily see just how toxic such seemingly innocent childhood play could become.) As Mr. Grimsley narrates his own life, we see ourselves, if we have eyes to see, that common habits, small phrases, typical customs, rituals and games and stories and social forces shape us deeply, encoding in us ways of seeing and ways of being. It is brave of him to tell his own story, and it illustrates much of what Smith is getting at in the first portion of You Are What You Love.

So that is the major project of the first part of You Are What You Love. We may be overtly taught things as true but we might end up caring for what may even be the opposite when our desires are conscripted into another story; if our hearts are calibrated to the tunes of other value systems or ways of orienting ourselves to the world, we will learn to love those things, regardless of what we’ve been taught or even what we claim we believe. Our ways of being are influenced by how we come to see life – in Smith’s explanation, what we come to desire – and our desires are usually caught, absorbed, breathed into the subconscious, snuck into our imaginations.

WHEN A BAD VISION OF HOME BETRAYS THE BIBLE VERSE DÉCOR

As Smith explains, in an example I myself have used for years, it matters little if one has plaques of Bible verses in one’s home if the family assumes wrong things about itself or is oriented around an non-Christian vision of family, home, or life: if dad is a brute or mom is a social climber or the kids are considered mere mechanisms for the parents to re-live their own dreams of eternal youth. If the values of the American Dream (individualism, upward mobility) have captured the heart of the family in one bad way or another, slapping a few Bible verses around the fiefdom isn’t going to sanctify it. The same can be said about a business, a counseling center, an art gallery, a school, or a church. Saying it is Christian, even loudly, doesn’t make it so, and what is imagined is more formative then what is asserted.

AN EXAMPLE FROM ROCK CONCERT WORSHIP

Smith has analyzed things like this in helpful ways for quite some time and at the risk of redundancy allow me to point you to the excellent chapter written as an open letter to modern praise bands and worship leaders in his anthology Discipleship in the Present Tense where he wonders if the forms of modern entertainment (the rock concert) have subtly influenced how contemporary worship is structured and perceived and experienced. He is not opposing contemporary worship as such, but asking in pastoral ways what other baggage comes along uninvited when  an (appropriate) structure/form from one arena (my pun intended) is inappropriately imported into another. That is, it is little wonder that those who grew up with “worship leaders” rocking out with lights and amps performing with cool affectations aping what they learned from rock stars for our consumption in worship experiences end up leaving a church if the musical stylings change or their favorite worship leader moves on. They’ve been taught – without any words but by the structures and forms and ethos and unspoken narratives, rituals, symbols – that worship is for me and an expression of my own heart and is to be taken in the same way I consume the experience of a big rock show. The “lessons” about what worship is and what it is about and how to participate have been “caught” no matter what is really taught. Even if a pastor or church school teacher verbally instructs more nuanced and proper views of worship, the ritual of how worship is experienced trumps. Smith’s dear letter in that book is much clearer and better written than my quick summary here and I commend it. It’s important for what it explores, but I mention it here as another example of the sorts of things that matter to him and that inspired YAWYL. We are not “brains on a stick” and our understandings of life usually are captured by stories and myths and values that are embedded in rituals, habit-forming liturgies.

an (appropriate) structure/form from one arena (my pun intended) is inappropriately imported into another. That is, it is little wonder that those who grew up with “worship leaders” rocking out with lights and amps performing with cool affectations aping what they learned from rock stars for our consumption in worship experiences end up leaving a church if the musical stylings change or their favorite worship leader moves on. They’ve been taught – without any words but by the structures and forms and ethos and unspoken narratives, rituals, symbols – that worship is for me and an expression of my own heart and is to be taken in the same way I consume the experience of a big rock show. The “lessons” about what worship is and what it is about and how to participate have been “caught” no matter what is really taught. Even if a pastor or church school teacher verbally instructs more nuanced and proper views of worship, the ritual of how worship is experienced trumps. Smith’s dear letter in that book is much clearer and better written than my quick summary here and I commend it. It’s important for what it explores, but I mention it here as another example of the sorts of things that matter to him and that inspired YAWYL. We are not “brains on a stick” and our understandings of life usually are captured by stories and myths and values that are embedded in rituals, habit-forming liturgies.

So, from James Grimsley learning to shed his (racist) skin in his recent memoir to Smith’s many helpful illustrations throughout this new book, we learn that rituals and habits matter, that most of what captures our heart and imagination and forms our deepest hungers and yearnings do not come from didactic teaching, but is picked up, caught, like the flu. Stuff is in the air, and unless our disciple-making programs and faith formation groups and spiritual direction sessions are rooted in robust, intentional, thick rituals of Christian worship, it is most likely that those programs and groups and sessions will be merely messing around the edges of people’s deepest lives. Their hearts will have already been captured by ways of seeing and serious dreams that were subconsciously absorbed from the secular liturgies in which they have participated.

Here is how Smith puts it, more eloquently and helpfully then my descriptions. In talking about healthy, historic forms of worship in contrast to the ubiquitous seeker-sensitive services, he writes,

The problem, of course, is that these “forms” are not just neutral containers or discardable conduits for a message. As we’ve seen already, what are embraced as merely fresh forms are, in fact, practices that are already oriented to a certain telos, a tacit vision of the good life. Indeed, I’ve tried to show that these cultural practices are liturgies in their own right precisely because they are oriented to a telos and are bent on shaping my loves and longings. The forms themselves are pedagogies of desire that teach us to construe and relate to the world in a loaded way. So when we distill the gospel message and embed it in the form of the mall, while we might think we are finding a fresh way for people to encounter Christ, in fact the very form of the practice is already loaded with a way of construing the world.

As he has explained in a previous chapter about the “liturgical” construction of the mall and the way a mere stroll through these “temples of consumerism” seduce and form us, he continues in his astute critique of mixing the subliminal messages of the mall and food court with church and worship,

The liturgy of the mall is a heart-level education in consumerism that construes everything as a commodity available to make me happy. When I encounter “Jesus” in such a liturgy, rather than encountering the living Lord of history, I am implicitly being taught that Jesus is one more commodity available to make me happy. And while I might want to add him to my shelf of stuff, we shouldn’t confuse this appropriation with discipleship.

BE AWARE. BE VIGILANTE. AND TELL A BETTER STORY THAT CAPTURES THE IMAGINATION

So, whether we are absorbing assumptions, which lead to disordered desires, from our habits of taking in secular liturgies, or absorbing those same bad assumptions by their being imported unwittingly by how we do church, we need to be vigilante. But we can’t just suppose that this is a matter of offering intellectual critique of bad ideas and replacing them with better points or principles. We need character and worldview formation of the deepest sort which include must deconstructing the influence of our secular liturgies and being intentional about how our imaginations might be sanctified by more appropriate, truly Christian liturgies, in church and in all of life.

Yes, we need to be on guard, and discerning out the habit-forming, love-directing, heart-capturing impact of modern life. But, mostly, we need to very wholistically and liturgically enter a better story.

There is really very little in print that opens all of this up so richly, and I want to suggest this book is nearly singular in its clarity and wisdom and importance. But that isn’t exactly right. At the very least, we should name a pair of other books that are in a similar ball park, by gifted authors who appreciate Smith’s work, and who Smith surely would commend: the spectacular volume Reordered Love, Reordered Lives: Learning the Deep Meaning of Happiness by David Naugle (Eerdmans; $18.00) and the beautifully-written reflection Teach Us to Want: Longing, Ambition & the Life of Faith by Jen Pollock Michel (IVP; $16.00.) If you liked those, you will love You Are… And if you are a Smith fan, you must know those two.

James Smith cites, more than once, a lovely bit of counsel from Antoine de Saint-Exupery, the author of The Little Prince that summarizes and captures much of the point. De Saint-Exupery writes,

James Smith cites, more than once, a lovely bit of counsel from Antoine de Saint-Exupery, the author of The Little Prince that summarizes and captures much of the point. De Saint-Exupery writes,

If you want to build a ship, don’t drum up people to collect wood and don’t assign them tasks and work, but rather teach them to long for the endless immensity of the sea.

You see (as Jamie explains),

To be human is to animated and oriented by some vision of the good life, some picture of what we think counts as “flourishing.” And we want that. We crave it. We desire it. This is why our most fundamental mode of orientation to the world is love. We are oriented by our longings, directed by our desires. We adopt ways of life that are indexed to such visions of the good life, not usually because we “think through” our options but rather because some picture captures our imagination.

WORSHIP RESTORES BY RE-STORYING US

And, for people of historic Christian faith, this “picture that captures our imagination” comes to us, most powerfully, in worship. As he puts it in one clever section, “worship restor(i)es us.”

Perhaps you can see why Smith dedicated this book to two of our most important writers and activists for worship renewal in our time, John Witvliet (founder of the highly regarded, exceptionally ecumenical, Calvin Institute on Christian Worship) and the late, great Robert Webber. He calls Witvliet a co-conspirator, and of Webber Smith writes,

Robert Webber’s work had a significant impact on me at a crucial phase of my life, and in many ways I’m simply writing in his wake. This little book is a dingy bobbing along behind the ship of Webber’s “ancient-future” corpus. If I can help a few people board the mother ship, my work here is done.

Robert Webber’s work had a significant impact on me at a crucial phase of my life, and in many ways I’m simply writing in his wake. This little book is a dingy bobbing along behind the ship of Webber’s “ancient-future” corpus. If I can help a few people board the mother ship, my work here is done.

I did not know Webber well at all; I was with him on two occasions, including once at a long and leisurely dinner that lead to a serious late-night conversation. I was surprised how much this Wheaton College worship scholar knew about my own unique journey – central Pennsylvania EUB boy whose imagination was captured by Kuyper et al and yet kept a foot in both mainline Protestantism and progressive evangelicalism, had done a stint at the radical Thomas Merton Center, and passionate about campus ministry and the CCO’s Jubilee conference. I was very grateful for our conversations. I think I understand why Jamie Smith found Robert Webber’s work so appealing and instructive for his own current project. Webber had a way of helping us “long for the endless immensity of the sea.”

SO MUCH MORE TO LEARN, TO APPRECIATE

You Are What You Love helps call us to a profound and embodied whole-life discipleship grounded in a deep Christian worldview – all of life redeemed, all creation ablaze with the presence of God, all followers of Christ equally called to vocation in the world – and helps us realize that this sort of truly transforming vision must grow deep in our lives not just by reading books about it or taking in podcasts or classes about it (betraying our assumptions that we are primarily “thinking things”) but, rather, our hearts and loves and desires must be converted and sanctified (indexed or curated, he might say) so that we are (re) oriented to the Christian story, not the American Dream. We need to appreciate “the spiritual power of habit” as the sub-title puts it and he explains how that happens, for ill (in the often very power secular liturgies) and sometimes for better (as we are shaped by thoughtful, intentionally crafted deep liturgies of historic Christian worship.)

Smith then does two major things in the remaining rich chapters.

WORSHIP AND HOW IT WORKS

First he writes wonderfully and wisely about worship.

In Chapter 3 he offers an excellent overview of “historic worship for a postmodern age.” It is excellent.

Then in chapter 4 – entitled “What Story Are You In? The Narrative Arc of Formative Christian Worship” – Smith offers what I take to be just about the best stuff I’ve ever read on worship. I have almost every sentence of every paragraph underlined and thought of many friends (mostly professional clergy or others involved in church work) would love it.

If just some of our pastors and worship leaders across the denominations could articulate this stuff in the way Smith does, or would articulate it, I think more and more folks would hunger for worshiping well, and would more deeply appreciate renewed forms and styles and aspects of worship renewal. (Heck, pastors, get your flocks yearning for more conversation and deeper appreciation of this stuff and they might free up more monies from the budget to send you to something like the annual Symposium on Worship of the Calvin Institute on Worship from which Smith has learned much of his insight about healthy, robust worship.) I respect so many pastors, including my own, and have been drawn to deeper worship by so many good liturgists, preachers, and worship leaders, that I do not want to be misunderstood. I am not trying to sound critical and certainly not cynical. But it is notable to me how little of this kind of stuff I have heard spoken out loud in our churches, in worship classes or adult forums. I really wish pastors and elders and worship planners would read this book, at least chapters 4.

A CONUNDRUM, A PARADOX, AN IRONY: THINKING ABOUT THE PRE-THEORETICAL

Ahh, I know, I know: if you are tracking with this you will see that I am still somewhat tied to a “thinking thing” view, that if only pastors would read this book, adopt these ideas, learn to explain this perspective, things would change. Yep, there it is, a basic irony of this book – it is a book demanding to be read and discussed by thinkers and explained, even taught, in churches. The role of the mind in all of this (which Smith affirms clearly on pages 6 and 7) is a bit of a mystery, but dare not be minimized (even if Smith perhaps unwittingly nearly does so throughout the book.)

It is my own contention that rituals (in this case, the habits and practices of deep Christian worship) might have a more powerful effect upon us if we understands what they are supposed to do to us. Not unlike other multi-faceted activities that are not primarily intellectual exercises — eating, making love, watching movies, say — by reading and learning about those those topics and understanding how they work in God’s good work, those experiences can then be fully engaged with the whole self, experienced better if one is aware or has some insight about what is going on. (We have a section in our bookstore called “books about books” for this very reason.) Perhaps it is a bit of a cycle — we are shaped by the pre-theoretical power of habits and liturgies, but those can impact us more fruitfully when we understand something about them. (I never knew that “passing the peace” in church was more than a time to greet one’s fellow pew-sitters with a hearty good morning, but was a freighted, liturgical act, a practice in hospitality and peacemaking. I hope that once I embraced a thicker account of what that part of the worship service was really about, what it was to be doing among us, that it could then make me a better peacemaker, and not just a guy who’s cheery as a greeter.) I assume Smith agrees that learning about how this gut-level stuff works is key, since he wrote such an impassioned and informative book for us to think about. Duh. Hearts and minds, after all; hearts and minds and bodies.

So, I believe it should be obvious that we can come to appreciate non-cognitive, pre-theoretical, imaginative influences and embrace their formative impact, even realizing they come to us most potently through ritual and story and habit-forming “liturgies” when we study and learn about it. Again, this may be a tad ironic but it isn’t contradictory. Of course we learn stuff by reading and thinking (it is what Smith is paid the big bucks to do, after all. ) His astute philosophical considerations (such as the embrace of a Dooyeweerdian view of worldview rooted in the human heart which set the stage for his embrace of the postmodern turn which rejected Cartesian dualism and the idol of autonomous rationalism) led him quite naturally to this realization that humans whom God has made as lovers are shaped also by — perhaps he is correct to say primarily by — dreams and visions, habits and rituals, rather than mere ideas deposited in the noggin. But that surely (surely!) doesn’t diminish the need for intellectual development, for thinking, talking, arguing, discerning the truth of his claims here, and the ways we might teach them in our faith communities and reform our practices. Even if he is only somewhat correct, we’ve got work to do.

So, ironic or not, I say again: this chapter on the “narrative arc of formative worship” is splendid, some of the best writing I’ve ever encountered on worship, short and sweet, radical and wise, useful and commendable. We need to learn this stuff. If your pastor or worship leaders don’t say these kinds of things from time to time, buy them this book, ASAP. Start a book club, even if it is just on the worship chapter, ready by your own worship planners or pastors, for starters. Implore them to explain this to the worshipers in your congregation. Help the ritual aspect of worshipful practices be more effective by helping the people of God understand.

AND THEN, LIVING IT OUT, DAY BY DAY BY DAY…

The last three chapters of You Are What You Love are worth their weight in gold.

The last three chapters of You Are What You Love are worth their weight in gold.

(What kind of metaphor is that, and why is “gold” so appealing to us? Ha! Maybe I should watch what I write, question what values are implicit even in how we talk, eh? Yeah, you can take that to the bank! Wink, wink.)

Seriously, one doesn’t have to be a linguist to observe that words we use shape how we think about things. The aforementioned Jim Grimsley writes passionately about how he came to value “whiteness” over “blackness” by the constant way our vocabulary affirms one as good and clean and the other as bad and scary. I don’t think Smith mentions the habits of speech and how they might subtly conscript us into ways of thinking and caring and acting…. one little piece of the puzzle he leaves unaddressed. (Although he has written a whole book somewhat about that, a heavy philosophy work published by Routledge called Speech and Theology.)

Chapter 5 of YAWYL is called “Guard Your Heart: Liturgies of the Home” and Chapter 6 is called “Teach Your Children Well: Learning By Heart.” Oh my, this is rich, good, stuff. Jamie is transparent about his own life, a bit, at least, and credits his wife, Deanna, for helping shape their own family’s desires and rhythms and home ethos, much of it learned at the kitchen table. She has a big heart and a lot of skills in home economics, hospitality seems to come natural to them, and she slowly got Jamie interested in eating more wholesome food and appreciating the finer tastes of a more normative diet.

This is shared in a lovely, helpful way, and he had already written nicely about his own need to change his diet, exercise and – of course – learn to want to do this. Knowing in his head proper stuff about food and nutrition, about health and stewardship, about global justice and sustainable agriculture, about feasting and fasting, wasn’t enough: one cannot think one’s way to new tastes. So his wife gets a whole lot of credit as helping guide the Smith household in Grand Rapids into new flavors, new tastes, new hungers, new lifestyles.

(Aside: you won’t want to miss a couple of pages about Smith learning to care more deeply about these things, and, literally, reading a Wendell Berry book eating a bad hotdog in the stupid food court at the big box, cost-cutting, mega-store, Costco. After making this rather humbling revelation he writes, “There are so many things wrong with that sentence I don’t know where to begin.” Kudos, Jamie, for sharing such a hilariously warped episode. “Reading Wendell Berry in Costco” is one of the great contemporary parables of our time, and a fabulous, fabulous few pages. It is fun and helps makes the point remarkably well.)

CULTURE-MAKERS, WORLD-CHANGERS, ORDINARY DISCIPLES IN LOVE WITH THE WORLD

As you might expect, as much as I loved the chapters on worship and agree with Smith’s insistence that intentional consideration of the significance of church life and Christian worship is essential, I really loved these chapters about how we worship God in all of life, see Christ’s redemption of all creation, and find ourselves in a story of the renewal of all creation. His last chapter on making a life called “You Make What You Want: Vocational Liturgies” almost made me cry. Oh, how I long for this kind of thing to be better known, to be in the bones and on the lips of my fellow Christians and the church leaders we know. Smith isn’t saying stuff that is that different or unusual or rare, really, yet his way of phrasing things, his vision of inviting people into a deeper, more meaningful sort of Christian discipleship, seems to me – and I suspect it will to you, too – nearly revolutionary in its freshness, its appeal, its implications. You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit is one of the most interesting, visionary, important books I’ve read in years.

As you might expect, as much as I loved the chapters on worship and agree with Smith’s insistence that intentional consideration of the significance of church life and Christian worship is essential, I really loved these chapters about how we worship God in all of life, see Christ’s redemption of all creation, and find ourselves in a story of the renewal of all creation. His last chapter on making a life called “You Make What You Want: Vocational Liturgies” almost made me cry. Oh, how I long for this kind of thing to be better known, to be in the bones and on the lips of my fellow Christians and the church leaders we know. Smith isn’t saying stuff that is that different or unusual or rare, really, yet his way of phrasing things, his vision of inviting people into a deeper, more meaningful sort of Christian discipleship, seems to me – and I suspect it will to you, too – nearly revolutionary in its freshness, its appeal, its implications. You Are What You Love: The Spiritual Power of Habit is one of the most interesting, visionary, important books I’ve read in years.

For instance, in a section called “Tradition for Innovation” he offers remarkable and rare wisdom (that is neither conservative nor liberal, traditionalist nor progressive.) He is grateful that many younger evangelicals are beginning to affirm an “expansive sense of mission and a more holistic theology of creation that affirms not only the Great Commission but also the cultural mandate.” But, on the other hand, he notes that evangelicalism continues to be a hotbed of almost unfettered religious innovation, ever confident of its ability to compete in the shifting marketplace of contemporary spirituality.

His concern is succinct and incisive:

The entrepreneurial independence of evangelical spirituality (which is as old as the American colonies) leaves room for all kinds of congregational start-ups that need little if any institutional support. Catering to more specialized niches, these start-ups are not beholden to liturgical forms or institutional legacies. Indeed, many of them confidently announce their desire to “reinvent church.”

These are, I want to suggest, competing trajectories. For we cannot hope to restore the world if we are constantly reinventing the church.

(An aside to those few who might care: does this conversation echo concerns of Nevin and Schaff of the 18th century Mercersburg Theology movement from German Reformed folks in Pennsylvania? That spiffy innovation and spirit of entrepreneurialism that marks passionate revivalism, while honorable for missional intensity, may be its own worst enemy? And isn’t this what Os Guinness predicted in his allegorical novel The Gravedigger File, now available as The Last Christian On Earth?)

Smith continues,

The cultural labor of restoration certainly requires imaginative innovation. Good culture-making requires that we imagine the world otherwise – which means seeing through the status-quo stories we’re told and instead envisioning kingdom come. We need new energy, new strategies, new initiates, new organizations, even new institutions. If we hope to put the world to rights, we need to think differently and act differently and build institutions that foster such action.

BUT GET THIS: HOW DO WE KNOW WHAT IT MEANS TO RESTORE?

But if our cultural work is going to be restorative – if it is going to put the world to rights – then we need imaginations that have absorbed a vision for how things ought to be. Our innovation and invention and creativity will need to be bathed in an eschatological vision of what the world is made for, what it’s called to be – what the prophets often described as shalom. Innovation for justice and shalom requires that we be regularly immersed in the story of God reconciling all things to himself.

And that happens in worship, and not just any kind of worship. So we are back to the interplay and relationship of the local church and our public faith, good worship and the good life.

As Smith puts it here, we need to be immersed “in intentional, historic, liturgical forms that carry the Story in ways that sink into our bones and seep into our unconscious.”

I cannot tell you how much I loved these last chapters of You Are What You Love, how I long to talk about them with others, to hear what you and your friends and fellowships make of it all. This book is one I want to promote, want to encourage you to buy and study and talk about and – please Lord! – maybe it will make a difference in how we worship and how we live.

VERY APROPOS THESE DAYS, A NECESSARY BOOK FOR OUR TIME

It will be a truly great read for those who are interested in cultural engagement and social action but wonder what kind of people we need to be to take up those vocations with lasting faith. In this regard, I might suggest it would appeal to those who were taken with the profoundity and eloquence of Steve Garber’s Fabric of Faithfulness: Weaving Together Belief and Behavior or Visions of Vocation: Common Grace for the Common Good or the fine work of Andy Crouch or any number of recent books or websites or local action groups helping us get involved in social action. If you were one of the many who viewed the Acton DVDs For the Life of the World, you really need to follow it up with a book just like this. If you appreciated Scot McNight’s call to root our public theology and Kingdom language in the local church (Kingdom Conspiracy: Returning to the Radical Mission of the Local Church) you will really appreciate You Are What You Love.

FOR ORDINARY CLERGY TOO

However, more conventional pastors of more ordinary churches will find much about this that will remind them of why they do what they do, how the language and symbols and rituals of the gathering, worshiping body are so very, very important. (Does anybody recall the important work decades ago of John Westerhof? Or does anybody use Godly Play curriculum? Or even appreciate the way some anti-hunger activists have rooted their local activism in the open celebration of the Lord’s Supper? That is, I think those who work with most common place stuff that goes on in typical churches will find in YAWYL a solace and a proverbial shot in the arm. I hope it is read among young and old, evangelicals and mainliners, those drawn to simple church and those from more high liturgical traditions. There is something here for everyone. I mean that with all my heart.

At the end of this fascinating journey, Smith offers to us a lovely blessing and a closing short piece he calls “Benediction.” It starts with the famous lines from T.S. Eliot’s “Little Gidding” about how after our exploring we come back to where we started “and know the place for the first time.” He then offers a lengthy quote from Russian Orthodox priest and theologian Alexander Schmemann , who wrote a very rich work called For the Life of the World which inspired the great DVDs by the same name. There, Schmemann reminds us of the significance of the word “Amen.” It’s quite profound.

Smith’s benediction?

“May you say ‘Amen’ to everything you love.”

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

10% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333