Please feel free to order these from us — we will deduct a complimentary 10% off discount on any item mentioned — by using our secure order form page. Just click on the link at the bottom. Happy reading.

What a season it has been for excellent, important, passionate interesting books.

A BookNotes post I did a week ago reviewed four (and mentioned more) very new books about public justice, an example of the shift these days where evangelical Christian thinkers and activists are doing some of the best books about living out faith in a broken and needy world. Look at that post and see if something tugs at your heart — they are important resources for your journey. And let’s affirm those publishers for doing these kinds of books, by making sure they are shared and promoted.

In our last Hearts & Minds post I described (for those who may not know) Os Guinness, a writer that I think is simply a “must read” – serious, mature, elegant and eloquent – who brings warning and insight and analysis and hope about our changing times. I described a few of the books he did the last few years, and described as best I could the brand new Impossible People: Christian Courage and the Struggle for the Soul of Civilization. It is published by InterVarsity Press (regularly priced at $20.00, but on sale from us for our BookNotes freinds.)

In our last Hearts & Minds post I described (for those who may not know) Os Guinness, a writer that I think is simply a “must read” – serious, mature, elegant and eloquent – who brings warning and insight and analysis and hope about our changing times. I described a few of the books he did the last few years, and described as best I could the brand new Impossible People: Christian Courage and the Struggle for the Soul of Civilization. It is published by InterVarsity Press (regularly priced at $20.00, but on sale from us for our BookNotes freinds.)

Since it is so important, and timely, here’s quick review of my review, for those that didn’t get to it:

After explaining how important Os has been to me personally, and how I admire his many books, I noted that those who know the book (or even know about the book) by James K.A. Smith entitled How (Not) to be Secular: Reading Charles Taylor will find Guinness’s Impossible People an inspiring read. Smith guides us through the dense word of world-class philosopher Charles Taylor to understand not so much what is lost in our secular age, but what has been added, a new way of being in the world and different ways of determining meaning. It is the same Taylor-esque lens, by the way, through which Robert Joustra and Alissa Wilkinson interpret the dystopian, end-of-the-world (or after-the-end-of-the-world-as-we-know-it) shows so popular these days, from the Walking Dead to Game of Thrones to Mad Men, in their extraordinary book How to Survive the Apocalypse.

Without citing Taylor, or even Smith, let alone zombies or sci-fi cylons, Guinness teaches us much about the forces of modernity, the pressure points and stresses — sometime intellectual/ ideological, but always material, including technologies, trends, customs, social arrangements, shopping patterns, laws, mores, media, entertainment, attitudes and postures, all which form habits that become what De Tocqueville called “habits of the heart.” If we think debating atheists or fighting rulings in the courts is the primary way to recovery greater good for our fraying society, if we think that faith is primarily lived out as a culture war, then we are fooling ourselves. Guinness gives us quite a bit more than Sociology 101, but this new book could serve as an overview of why mere anti-atheist apologetics or why mere “cultural engagement” or why just doing “social justice” work isn’t enough, although he is fully committed to each of those aspects of faithful discipleship and has spoken articulately about them all. Obviously, the truth of historic, orthodox faith must be nurtured in our churches as the Word of God is proclaimed with authority and relevance. As he so beautifully wrote in Renaissance (a companion volume to Impossible People) we can be people of hope as we do God’s work in God’s ways and learn to trust that Christ’s Kingdom comes less through our cultural machinations but through the mysterious work of the Spirit.

In this, Os — although terse in his rebuke of thoroughly revisionist Christian writers, pastors and church leaders who have severed ties with historic, classic orthodoxy — is hopeful and properly ecumenical. Many in various denominations and faith traditions are united in broad hope for church revitalization of the sort that leads by God’s grace to authentic cultural renewal and he is gladly appreciative of Christians of various persuasions and denominations who desire to live boldly for Christ.

Still, we have to be more savvy about how not to capitulate to the ways of living swallowing us up, almost without notice, by the forces of modernity and late modern capitalism. We have to be on guard that our enjoyment of choice and change in our shopping or on-line entertainment, for instance, doesn’t somehow color historic theological truths and spiritual practices, as if we are just shopping for beliefs that suit our wishes that day. (The customer is always right, you know, and how does thinking of ourselves continually as “consumers” effect our self image and our tendencies even as we think about our religion?) Inevitably, though, resistant as we may be, our imaginations are often too-easily captured by the ways of the world, which is why Romans 12:1-2 calls for radical non-conformity and the renewal of the mind, lived out in our real-world bodies; life as worship. Without directly linking his call in Impossible People to these texts, it is essentially a guide for living out their thrilling vision. If you count those two verses among your favorite, you need this book. If you don’t know those two pivotal verses, perhaps you really need this book!

Again, it is interesting to compare Impossible People: Christian Courage and the Struggle for the Soul of Civilization and how it pushes us (with a different style and approach) to take seriously what Jamie Smith teaches in his cultural liturgies project (the serious, meaty Desiring the Kingdom and Imagining the Kingdom and the much-discussed, nicely done You Are What You Love.) If you are reading James K.A. Smith, I think you’d benefit from Dr. Os Guinness. If you intend to read Guinness, you will surely want to add in some Jamie Smith.

Once we learn, or reconsider the urgency of resisting cultural accommodation, even gaining guidance on how to more spiritually discern the impact of the principalities and powers — Guinness cautiously draws on the work of Walter Wink (Naming the Powers, Unmasking the Powers, Engaging the Powers) to remind us of what is at stake in resisting evil’s thrust — we will have to double down in humble submission to the ways of God, learn to be people of trust and obedience, of prayer and spiritual strength. We simply must be clear about the first things of the gospel. We must become more Christ-like and courageous, humble but principled, working hard to become people who are so deeply committed that we become the impossible ones of the book’s title. We will be the sort who are unable to be bought off, not concerned with fashion or status, power or privilege. We cannot be beaten down — “unclubbable” is an old fashioned word the vivid writer George Orwell used to describe those who live with such firm resolve. Guinness’s insights are truly striking, his knowledge tremendous, his concerns important, his writing exceptional, and his new book, even when it is stern, is a blessing. It is one of the most important titles of the year.

Sorry to repeat some of what I said last time. I summarized that last BookNotes post here because I’m told some people missed it last week, and I certainly would be sad if you didn’t consider it – I worked hard to explain it all, earnestly trying to let folks know that Guinness’s book is an important work. I do hope you read my review, long as it was.

But I also review it now because it in some ways sets the table, or offers some sort of framework, for the exceptional importance of the two books I want to tell you about now.

Oh my, this is going to be fun.

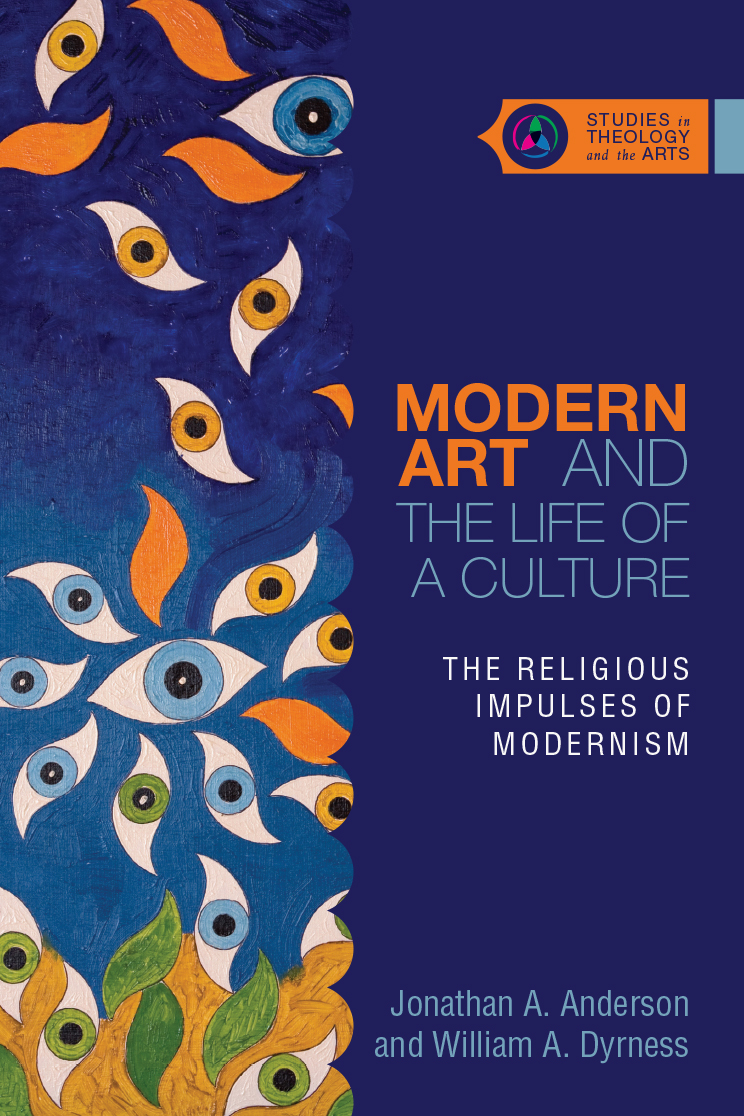

One is a long, serious, study, admittedly not for everyone, but truly a major contribution to the development of a Christian view of modern history – art history, to be precise. It is called Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism by Jonathan Anderson & William Dyrness (IVP Academic; $24.00) and I hope you enjoy my remarks about it; I am sure you will see the connections to the big picture overview of modernity that Dr. Guinness sketches for us. I will describe it for you shortly.

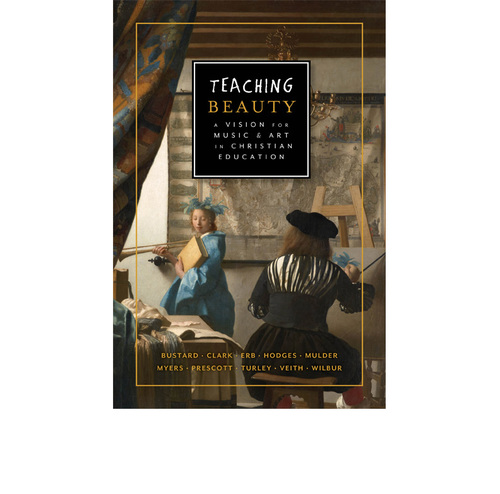

The other brand new book is relatively short (159 pages) published from a small set of talks that were given at a conference reflecting on how teachers (in Christian schools) can be more wise and faithful in teaching the fine arts. I loved reading this and am convinced it should be read beyond the obvious audience of teachers. Teaching Beauty: A Vision for Music & Art in Christian Education was edited by G. Tyler Fischer & Ned Bustard (Square Halo Books; $24.99) and is a wonderfully enjoyable book, a book that almost anyone can appreciate and which many will want to discuss, debate, and pass on to anyone who has any influence over the education of our children (including, I’d think, parents and youth workers.) It is not well known, but I hope we can change that — it deserves to be known!

The two books are both excellent in their own way, yet both very different. It seems right to mention them together.

Teaching Beauty: A Vision for Music & Art in Christian Education edited by G. Tyler Fischer & Ned Bustard (Square Halo Books) $24.99

Teaching Beauty: A Vision for Music & Art in Christian Education edited by G. Tyler Fischer & Ned Bustard (Square Halo Books) $24.99

Like all of the best books, there is a bit of a story behind Teaching Beauty. For what it is worth, these chapters were delivered live in March of 2010 – a few have a lively, chatty tone, while a few were more formal academic papers, complete with great footnotes – at a small conference hosted by the Veritas Academy, a classical Christian school in Lancaster PA. The event from which these chapters were drawn was called The Veritas Academy Fine Arts Symposium and they are great for anyone who likes to think about serious Christian cultural engagement, who enjoys books about the arts, or who likes to hear about renewal happening in educational reforms. I found myself wanting to underline sentence after sentence (and found myself provoked to think, too – why did this or that section annoy me so?) so that I didn’t want to put it down, chapter by chapter drawing me on, reading it almost in two straight sittings. It is an ideal book for many of us as it isn’t too academic or weighty (although it certainly isn’t light-weight) nor too extensive, although one surely gets one’s money’s worth with 11 chapters and a handful of useful appendices. The chapters are quite motivational and none are too long. Published by a small, craft publisher who cares deeply about all of this, I hope you’d appreciate the indie feel and purchase it soon. Who knows, maybe there is somebody you could bless by giving it away once you’ve read it.

Some of the contributors to Teaching Beauty are educators themselves and they are all well-schooled in history, philosophy, theology, the flow of ideas, the importance of virtue, and the way the gospel invites us to a nearly sacramental worldview. Classical educators are nothing if not really smart. What a great gathering of women and men this was with slightly differing views, but in agreement that the Earth is the Lord’s and we can take delight in its bounty. To a person, they value the arts as God’s good gift for God’s good world, and several cite one of my all-time favorite books, Rainbows for a Fallen World, a study of aesthetics by Calvin Seerveld.

After a very fine introductory chapter opening with a line from Dante, written by Veritas Academy Headmaster Ty Fischer (“Art as a Guide to the Sacred”) the next two chapters of Teaching Beauty are spectacular – kudos to Square Halo for bringing these essays to us. And what a treat it all is.

The first chapter is by Ken Myers. Maybe you know Ken Myers who offers the subscription  audio magazine called The Mars Hill Audio Journal. If you read Ken’s pieces that sometimes appear at his fabulous website, or listen to his ruminations with his guests – the show is produced like a set of NPR features, although a bit more intellectual than most – you will know he is very, very interested in the same concerns Os Guinness raises in the above mentioned Impossible People book; that is, how do the forms and styles and habits of a modern consumer society influence our social imaginaries? What does it mean to be “in the world but not of it” as we consider the subtle influences of our 21st century society and up-the-the-minute zeitgeist we breath in? Ken Myers knows well the work of Jamie Smith – not just his introduction to Charles Taylor (again, named above), but his vibrant You Are What You Love and “cultural liturgies” project – so many of our customers will love that about him. He appreciates the localism of Wendell Berry; again, this is thoughtful, wise, interesting stuff that I would think many of our customers would enjoy.

audio magazine called The Mars Hill Audio Journal. If you read Ken’s pieces that sometimes appear at his fabulous website, or listen to his ruminations with his guests – the show is produced like a set of NPR features, although a bit more intellectual than most – you will know he is very, very interested in the same concerns Os Guinness raises in the above mentioned Impossible People book; that is, how do the forms and styles and habits of a modern consumer society influence our social imaginaries? What does it mean to be “in the world but not of it” as we consider the subtle influences of our 21st century society and up-the-the-minute zeitgeist we breath in? Ken Myers knows well the work of Jamie Smith – not just his introduction to Charles Taylor (again, named above), but his vibrant You Are What You Love and “cultural liturgies” project – so many of our customers will love that about him. He appreciates the localism of Wendell Berry; again, this is thoughtful, wise, interesting stuff that I would think many of our customers would enjoy.

Myers is very concerned about how a tradition of practices is transmitted, and how the power of that is eroded in a self-centered (de-centered?) modern culture. So, his chapter on “Sustaining a Fine Arts Education in a Consumer Society” is astute and very, very important. How can we teach youngsters to submit to a way of learning and a body of wisdom that has come before if they are cut off from all notions of the past, and from any mediating structures that help them experience such embeddedness? His story tracing who studied under who – starting with an influential high school music teacher he met in his own youth all the way back to Bach!! – was thrilling, and made his point well.

Such a hard-hitting critique of consumerism isn’t what one often hears on the conservative side of evangelicalism, although his profound analysis of capitalism’s dangers aren’t the sort usually spoken by most social justice advocates, either. You see, Myers does much more than lament our materialism, our shopping, as such. He’s exploring what Marx meant when he said that “everything solid melts into air” and what Guinness exposes when he explores the impact of choice and change upon traditions and values. Ken Myers’s overview of how to inform and develop a desire for the good and the beautiful and how doing so is a counter-cultural practice (given our disinterest in history and our fast-paced embrace of the moment) is brilliant. It is important, I’d say, not just for art and music educators, but for all of us, living as we do in these times. It certainly sets the table well for the feast of papers that follows.

Myers isn’t too heady, but he is intellectually stimulating. His (brief) critique of Kant’s influence in the high-Enlightenment era – causing us to now think of aesthetics in purely subjective terms – is essential for this whole project and is a painless way to get up to speed on this topic. But he (like Guinness, and one of Guinness’s intellectual mentors, Peter Berger) knows that merely analyzing the influence of bad ideas isn’t an adequate way to analysis our current malaise (in culture, or in arts education, generally.) Myers not only exposes relativism (from Kant) but how social experience influences us less consciously. He goes after consumerism, like this:

The consumer worldview perceives the world as raw material, not a sacred trust requiring sacrificial stewardship. The consumer worldview regards culture as a series of autonomously selected commodities, not a valuable inheritance. The consumer worldview is an orientation toward creation and toward culture that promotes the modern ideal of the sovereign self.

To see culture as an inheritance which we must steward and contribute to is very different, and offers a different starting point to think about enjoyment of the arts and music, and certainly to think about arts education. Art is not fundamentally about self-expression, a view of the artistic endeavor tied up with Enlightenment views of the autonomous self, and which usually sees emotive expression as a counter to the elevation of reason in the philosophy of Rationalism.

Myers (like several other authors in the book) does a little philosophical archeology here, but he shows just how important it is by drawing on Christian Smith’s important study of what older teens believe these days, Souls in Transition: The Religious and Spiritual Lives of Emerging Adults (popularized in Kenda Creasy Dean’s Oxford University Press hardback, Almost Christian: What the Faith of Our Teenagers Is Telling the American Church.) Smith and Dean tell us about how older teens, even those involved in churches, are so thoroughly modern, with little language to talk about truth or goodness or beauty (or even God, for that matter.) Our faith communities have, almost across the board of denominations, their research shows, failed our youth by not successfully transmitting to them giving strong foundations for thinking about and talking about faith and life. The erosion of generation to generation traditions is painfully obvious, and it matters.

It is an arrogant assumption to think that history doesn’t matter, that old stuff can’t be right, the boundaries offered by Biblical truth represses kids, that classic formulations are hindrances to self expression, as if that is the key to the happy, good life. Cue Frank Sinatra’s “I Did It My Way” or his pal Sammy Davis Jr’s “I Gotta Be Me” right about here, or for that matters, John Lennon’s rocking “Whatever Gets You Through the Night” or any number of hits playing on the radio this very week.

But this is the way young adults have developed their view of God and culture and purpose and meaning, drifting feebly because for whatever reasons, even good churches haven’t been able to give them strong words to convey a vision of God and the good life other than what Smith calls “moralistic therapeutic deism” or strong enough practices to deeply shape the desires of their hearts.

Ken Myers moves from a succinct but profound critique of secularizing modernity to a vivid Christian vision where creation is a gratuitous epiphany, and submission to the real leads us away from individualism and gnosticism and shallow, feel-good religiosity; his great chapter in Teaching Beauty shows how learning the very forms and structures and ways of ordering life inspired by music and art can enliven us as humans and, of course, deepen us as Christians.

Ken’s reading is wide and sophisticated and his comments so blessedly well-informed that it is almost worth the price of the book to read this one chapter. He moves adeptly from the Canadian philosopher George Grant to Jesuit poet Gerard Manley Hopkins, from Reformed theologian Peter Leithart to the former Archbishop of Canterbury Rowan Williams, from the Orthodox historian Jaroslav Pelikan to Orthodox scholar David Bentley Hart, from the lively cultural historian Jackson Lears to the dense, dense, Colin Gunton.

Here Myers cites and tells about Josef Pieper, to help us get at a way of seeing, even a way of knowing, that is deeply human and more than rationalistic. (That he has had Esther Meek and Steve Garber on his audio journal talking about this covenantal way of knowing and appreciates the work of philosopher of science Michael Polanyi doesn’t hurt, either. He’s so good at this…)

The Catholic philosopher Josef Pieper has a little book of essays called Only the Lover Sings: Art and Contemplation, in which he observes that “to contemplate means first of all to see – and not to think.” This kind of seeing is receptive and open, not just accurate; as practiced by artists, it is not unlike the tradition of contemplative prayer, and is thus another link between worship and the arts.

Despite this amazingly rich way of thinking about knowing and seeing and the task of the artist, I have to say, for what it is worth, that Ken may not be as resistant to the influences of modernity as he thinks he is, and his assumptions about aesthetics might be refined, made more deeply Christian, by adopting the ways in which authors like Calvin Seerveld and Nicholas Wolterstorff, have critiqued the conventional notion of beauty.

(Okay, I’m on a roll, so might I  suggest, if you are seriously thinking and teaching about all this — like every author in this book, that is — you should at least read some of the key pieces in Calvin Seerveld’s Normative Aesthetics [Dordt College Press; $21.00.]) I would read Ken Myers regardless, but besides his seemingly unreformed adaptation of “beauty” as a norm for the arts, there is something that some might call elitist hovering around all this. I guess the classical schools educators might think this a cheap shot, and I don’t mean it as such.

suggest, if you are seriously thinking and teaching about all this — like every author in this book, that is — you should at least read some of the key pieces in Calvin Seerveld’s Normative Aesthetics [Dordt College Press; $21.00.]) I would read Ken Myers regardless, but besides his seemingly unreformed adaptation of “beauty” as a norm for the arts, there is something that some might call elitist hovering around all this. I guess the classical schools educators might think this a cheap shot, and I don’t mean it as such.

Such anti-modern assumptions, and the talk about the virtue of “the beautiful” leading to elitist (or, at least, high-culture) approaches, are, in my view, a nearly fatal flaw of the entire classical education movement, no matter how fastidious they are about Reformed theology and proper doctrine; they are too religiously loyal to (pagan) Greek thought — the essays here (many of which share this assumption about the value of “the good, the true and the beautiful” as a faithful umbrella under which to do the Lord’s work) are anti-modernist, happily, but seem nonplussed by their own accommodation to sources and ways of thinking that are, in others ways, perhaps also anti-Biblical.

For instance, I think there is much value in John Mason Hodge’s piece (“Beauty in Music: Inspiration and Excellence”) and commend it to you. I would be glad for anyone saying this sort of thing in any school, Christian or otherwise, as it is so remarkably thoughtful and interesting and important, to raise the stakes of why we should think about music in our culture. Further he is not only a respected scholar but is an experienced symphonic conductor and an esteemed classical musician. Having said that, I still fretted about his drawing on Plato as much as he did, affirming Greek notions of order and harmony – where is that in the Bible, really? – and drawing on peculiar thinkers like Pythagoras and “the music of the spheres.” There’s nothing wrong with studying “The Greek Muses” although it is odd that an evangelical would cite Exodus 31:2 in perfunctory passing, but spend much more energy singing the praises of Calloipe, Clio, Erato, Euterpe and the other offspring of the evil Zeus. What’s going on here? Why does he simply assert the necessity of “unity and diversity” in any good art piece? I actually really like where Hodges ended up with his chapter – writing about a sacramental worldview and the purpose of music (even if I disapprove of his wanting to “relate” matter and spirit, a huge concession to pagan thought which ought to be denounced.) Read with critical discernment, this stuff is stimulating and well worth pondering.

(And, an important aside: as we think about the very commonly assumed distinctions between high and low culture, I’d suggest a careful study of the groundbreaking, historically informed and deeply insightful Pop Culture Wars: Religion and the Role of Entertainment in American Life by William D. Romanowski of Calvin College [Wipf & Stock; $45.00.])

Ken Myers himself isn’t involved in the “classical education” movement, and says so, and it is to their credit that this group of classical school teachers brought him to Lancaster to kick off their days of reflection. Still, he’s got this fascinating (and not unimportant) interest in how the harmony and orderedness of art and music reflects the nature of God, a line of thinking that has been rejected by many reformational philosophers of aesthetics.

For instance, Myers’s cites David Bentley Hart, writing beautifully about the infinite love experienced by the members of the Trinity. Myers writes,

Hart goes on to suggest that the relationships among the members of the Trinity are not only beautiful, they are beautiful in a way that has analogies with our experience of music…. If Hart is right, then the presence of music in our worship and in our lives is witness to a deep reality of difference and unity in Creation, which itself has its sources in the inner life of the Triune God.

I’m not sure seeing art as pointing us to the attributes of God, rather than the creation itself, is the most faithful way to think about the human calling of doing art or the point of experiencing it. But that’s an in-house debate about aesthetic theory and I suppose above my own pay grade. But the practical upshot, for Myers is right on:

Art provides us with ways of perceiving reality aright, although not all art does this, or does it well. And not all of us have allowed our imaginations to be disciplined to encourage that perception.

And that is a major theme of this great little Square Halo book. In almost all of the essays we have ideas about how schooling can discipline us to perceive reality aright, of how to help shape desire, bending it towards the good, hints of how education can inform and inspire and transform us, how our dispositions can be reformed (what Jamie Smith calls “the recalibration of the heart”) so that we have new tastes, not just more data, more wisdom, not just more information. Indeed, one great chapter is on the “aesthetics of classical education” by Stephen Richard Turley is called “Redeeming the Senses.” Dr. Turley is a teacher of Theology, Greek, and Rhetoric at Tall Oaks Classical School in Delaware and a professor of Fine Arts at Eastern University. Wow.

So here is what I think: even if I don’t quite appreciate all of the classical fetish with Greco-Roman ways (even when they dress it up with Calvin and Chesterton and quote The Abolition of Man and their Patron Saint Dorothy Sayers and her trivium and love for Latin) and even though I think they are woefully wrong in not adequately seeing “common grace” in the popular culture of rock and pop and rap, they are mostly right in insisting that there is much, much work to be done in thinking faithfully about serious arts education In our schools; they are right in grounding that project not in Romantic self-expression, but in submitting to good traditions and virtuous insights of the past. I cannot say how glad I am that this Veritas Symposium’s reflections are now available for all of us, maybe especially those of us not connected to the classical schooling movement, who might otherwise not get to read this kind of stuff very often. As I regularly say, agree or not with every sentence, I heartily commend this book.

The blessedness of this (radical?) way of thinking about good art and teaching it well (and how different it is from more commonly used approaches by too hip art teachers trying their best, untrained in aesthetics, or even art history, as they are) was illustrated in a story told in Gene Edward Veith’s fantastic chapter (another chapter that, even if I quibble a tiny bit, was worth reading twice!)

Veith tells of a Lutheran school in Casper Wyoming where five years olds were being shown and taught about great art. (Of course, most art programs just give little ones paste and crayons and allow them to mess around, which is lovely and fun and valuable in many ways, but a far cry from serious arts education.) During a field trip to the local art museum, the children were appalled by the museum’s children’s exhibit, that – in some goofy effort to make art appealing to kids – had the Mona Lisa with a cowboy hat. The Lutheran kids were indignant. “She wasn’t a cowgirl!” they exclaimed to the docent. “She was painted by Leonard da Vinci during the Renaissance!”

Veith continued,

Throughout the tour, the children were picking up the styles and genres they were seeing: “That’s impressionism!” “Look at that landscape!”

The docent was astonished at the level of artistic sophistication she saw in these five-year olds. She concluded that since she was not that conversant with art history, being a product of progressive education, some of these little kids knew more about art than she did.

Amazing.

The manager of Square Halo Books, Ned Bustard, has a chapter in here that is fantastic. With a lighter, clever tone, Ned reminded the conference participants that as they help children and youth come to a deeper appreciate of art and music in God’s world, it could lead to trouble; that is, it is hard to make a living as an artist in our culture, and if even a few respond to a holy sense of vocation, being called into the world of the arts, they must be prepared to be perceived as not as serious as those with more “useful” careers. It is legendary how the arts are viewed as a waste (professionally speaking a least) and yet, Bustard playfully twists that a bit, asking if maybe it is so: there really is a gratuitous, wastefulness to art – it doesn’t do – anything, really. He draws on Seerveld and tells about interviews with artists and quotes those who have written in books he has edited such as It Was Good: Making Art to the Glory of God and It Was Good: Making Music to the Glory of God. Who knew that Ned started out as a business major and that Francis Schaeffer (Art and the Bible) and Madeline L’Engle (Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art) “saved not just my art, but also my soul. Art and the Bible gave me a theology that made room for art and Walking on Water filled that room near to bursting.” Indeed, there are many wastes we cherish.

The manager of Square Halo Books, Ned Bustard, has a chapter in here that is fantastic. With a lighter, clever tone, Ned reminded the conference participants that as they help children and youth come to a deeper appreciate of art and music in God’s world, it could lead to trouble; that is, it is hard to make a living as an artist in our culture, and if even a few respond to a holy sense of vocation, being called into the world of the arts, they must be prepared to be perceived as not as serious as those with more “useful” careers. It is legendary how the arts are viewed as a waste (professionally speaking a least) and yet, Bustard playfully twists that a bit, asking if maybe it is so: there really is a gratuitous, wastefulness to art – it doesn’t do – anything, really. He draws on Seerveld and tells about interviews with artists and quotes those who have written in books he has edited such as It Was Good: Making Art to the Glory of God and It Was Good: Making Music to the Glory of God. Who knew that Ned started out as a business major and that Francis Schaeffer (Art and the Bible) and Madeline L’Engle (Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art) “saved not just my art, but also my soul. Art and the Bible gave me a theology that made room for art and Walking on Water filled that room near to bursting.” Indeed, there are many wastes we cherish.

I love how Ned weaves together his personal story, his friendship with art historian James Romaine and tells how he has strolled through museums (with his children in tow) with esteemed artists such as Ed Knippers or Mako Fujimura. And, how he cites N.T. Wright, from Simply Christian,

The arts are not pretty but irrelevant bits around the border of reality. There are highways into the center of a reality that cannot be glimpsed, let alone grasped, any other way. The present world is good, but broken and in any case incomplete; art of all kinds enables us to understand that paradox in its many dimensions.

Ned’s chapter not only makes a delightful case for “knowing beauty” and “art and the kingdom” but he shares the “poetic underpinnings” of their own homeschooling efforts, bringing an awareness of aesthetics and the arts to their own educational work. (Ned, you should know, has recently created for Veritas Press a major art curriculum for children, which we will be reviewing more thoroughly soon.) You will love his call to “put beauty into practice” and his honest report of how he and Leslie did the best they could with the resources they had. Taking time to pursue these things sometimes seems (again) less productive, but after reading this chapter, you, too, will want to evaluate how you can deepen your experience with the aesthetic dimension of daily life, and how you can allow art to play a more intentional part of your life. His practical pointers will make the task seem approachable, and fun.

Bustard’s isn’t the only practical chapter, even if all are framed by a very thoughtful vision of deeper things. I loved Karen Mulder’s broad and brilliant chapter, “Balancing Binaries: Teaching Appreciation in the Visual Arts” which named many authors and books indicating her remarkably fluent familiarity with the best of Christian considerations, Catholic, Protestant, evangelical and beyond. Her visionary manifesto was practical in that it invited us to continue the conversation, join professional associations, find a cohort, and nurture others wisely to deepen the general movement of serious Christians in the real world of arts. My hat is off to her! David Erb, whose own Master’s was from the Westminster College Choir at Princeton,and whose PhD is in Choral Conducting from the University of Wisconsin, is now involved in the choral community in a university town, has a piece called “Sing with Understanding, Play Skillfully: Musical Literacy for All the Saints.” Speaking of practical, there’s a useful appendix called “How to Hire a Fine Arts Teacher” (one pointer: have him or her make a pledge to be friends with the math teacher) and a set of charts offering curricular objectives for various ages. What a great little resource for or parents or teachers or church educators.

But, again, I hope I am clear in saying this is not just a book for those working in classical Christian schools, or even for those who are working in Christian schools. In fact, it’s not even just for those who are in schools. Parents, choir-directors, church school teachers, Christian ed professionals all will all be informed and aided in their efforts to think well about shaping the lives of those God has given them to influence. Anybody who wants to learn more – maybe not having been schooled in aesthetics all (which, as they document, maybe include even art teachers and many with MFA degrees! – will benefit from listening in to these thinkers and educators about how to teach music and art within a context of learning to love goodness, truth, and beauty.

I truly respect Ken Meyers, and am so excited to see his chapter here. I mentioned that I read Gene Veith’s chapter twice, and it is great. I loved Ned’s chapter – a lot, actually – and I have admired Karen Mulder for years and her piece is exceptionally helpful, a great primer.

I think, though, the chapter that thrilled me most was by Theodore Prescott, a legendary artist and art educator, the former head of the excellent art department at nearby Messiah College. Ted became a Christian as a college age student and a very young artist. He has thought as deeply as almost anyone I know about aesthetics and creativity and art and beauty, but he has done so as a working artist and a college teacher and mentor. He has been a significant leader of CIVA (Christians in the Visual Arts) and has produced much good art, good scholarship, and born fruit in releasing many serious young artists and art teachers into the world. I have enjoyed hearing him speak on occasion and respect him immensely.

His chapter cuts to the chase: “Jerusalem, Athens, and the Education of Young Artists.” I hope you get his allusion to the early church leader, Tertullian, who, even then, pondered deeply the relationship between the Judeo-Christian community (Jerusalem) and the pagan centers of thought, power, and culture (Athens.) This is the question for those of us in mainline denominational circles who seem easily accommodated to the ways of the status quo society in which they are so established. It is the question for the emerging church folks, who seem quite eager to accommodate themselves (albeit missionally) to the hip trends of the postmodern counterculture. It is also the question for the classical educators who seem so unashamed to root their thinking so uncritically in the school of Athens.

But that is my own sense of why Ted’s piece is important – it invites us to ask how to navigate all these complex waters. His presentation at the conference must have been inspiring; the chapter isn’t all that philosophical and not at all pedantic. Ted is a deeply Christian educator and offers great, mature insight from years of experience helping church kids learn to think more deeply about their calling into the vocation of the arts. It is as concise a manifesto for developing a Christian view of the arts as I’ve seen, and it is a marvelous, deep, joy to be able to commend it to you.

The last, short, chapter of Teaching Beauty: A Vision for Music and Art in Christian Education is plain and remarkable and needs to be read and discussed. Matthew L. Clark is a woodcutter and printmaker and his chapter is called “Art and Charity.” It is a very helpful call to be more generous in our appreciation of art and artists (especially modern art.) He even uses the Bible word “submission” as a principle which contrasts with what some literary authors have called the cynical “hermeneutic of suspicion.” Matt is a very good musician and a very talent artist himself; I value his contribution here and the Symposium and the book editors for arranging it. This consideration is a good way to end, on a note not of criticism or concern, or even of zealous cultural transformation, but simply on openness and kindness.

It is charitable to believe the best about someone and something they have made until you have reasons to believe otherwise. Some artwork is difficult and perhaps it is not immediately accessible. That should not be an insurmountable barrier to appreciation. Many good things are, at first, inaccessible to us. It takes time to develop a taste and to understand why a thing is held in such high regard by so many. It may turn out that many people are simply wrong. Of course, it may turn out that your initial reaction is the one that needs reconsideration.

There is more here. There is a document offered as an appendix which they have called the Lancaster Declaration on Classical Christian Education and the Arts. That their small central Pennsylvania symposium in 2010 drafted this statement may not strike you as all that important, or interesting. (What even is classical education, you may be asking?) But I want to sound my bookseller’s/educator’s note again: this is a very rich and stimulating, generative document, curious as it may be. It would be a fun thing to talk about if you are an art or music major in college (or if you are a campus minister serving students in art or music educational programs.) It would be a fabulous to talk about it with friends over coffee. Pastors, youth leaders, anyone wanting to influence others to think about the good, the true, and the beautiful, need to (re)visit these themes from time to time, and this Declaration offers it succinctly. This bold set of assertion and guidelines for practices would be a great resource to use to generate on-going conversation in your family, fellowship, or church community. And certainly, if you are connected to a religious school, it is simply a must.

There is more here. There is a document offered as an appendix which they have called the Lancaster Declaration on Classical Christian Education and the Arts. That their small central Pennsylvania symposium in 2010 drafted this statement may not strike you as all that important, or interesting. (What even is classical education, you may be asking?) But I want to sound my bookseller’s/educator’s note again: this is a very rich and stimulating, generative document, curious as it may be. It would be a fun thing to talk about if you are an art or music major in college (or if you are a campus minister serving students in art or music educational programs.) It would be a fabulous to talk about it with friends over coffee. Pastors, youth leaders, anyone wanting to influence others to think about the good, the true, and the beautiful, need to (re)visit these themes from time to time, and this Declaration offers it succinctly. This bold set of assertion and guidelines for practices would be a great resource to use to generate on-going conversation in your family, fellowship, or church community. And certainly, if you are connected to a religious school, it is simply a must.

Thanks be to God for these dedicated folks who put these papers together and called this gathering. Thanks be to God for Square Halo, for investing their own finances in order to publish a limited number of this great little book, Teaching Beauty: A Vision for Music and Art in Christian Education. Order it today!

Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism by Jonathan Anderson & William Dyrness (IVP Academic; $24.00) is nothing short of magisterial, a work years in the making, and I am thrilled to tell you about it, even if I realize not everyone will buy it.

Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism by Jonathan Anderson & William Dyrness (IVP Academic; $24.00) is nothing short of magisterial, a work years in the making, and I am thrilled to tell you about it, even if I realize not everyone will buy it.

Interestingly, there is a connection to the aforementioned Os Guinness. Modern Art and the Life… begins with a fabulous, fabulous chapter in tribute to Dr. Hans Rookmaaker, a person who I believe was a friend of Os Guinness. Rookmaaker was a Dutch art historian (who came to Christian faith in a Nazi concentration camp, by the way, led to salvation by a fellow prisoner, a Dutch philosopher.) His impact at L’Abri and elsewhere — offering lectures on American blues and jazz, knowing much about modern art, offering the reformational philosophy of Herman Dooyeweerd to other scholars — is legendary. His small book Art Needs No Justification is in print again, and is a vital example of his impact among aspiring Christian artists at the end of the 20th century. Professor Rookmaaker had a certain pessimistic view of the Enlightenment and consequently a certain critique of modernity (drawing significantly from Abraham Kuyper, who was seriously opposed to the French Revolution) and it informed his particular interpretation of our the story of the West that retains much, much insight.

Grounded in that profound, critical assessment of the eroding forces of the Enlightenment, and the intellectual idolatry pervasive to secular rationalism — think only for yourself said Kant, smash the infamous (Christian church), said Voltaire, tip your hat to no man, Whitman later  preached — Rookmaaker then told the story about his own love for the arts, even the very contemporary arts of his mid-twentieth century world. His book Modern Art and the Death of a Culture remains a very important work for many, many of my peers and heroes. I do recall, before understanding much of it (and understanding how much of it was misunderstood!) a college pal startling me by throwing it across the room. (You know who you are!) Alas, it ends up that Rookmaaker was a cultural and intellectual genius and a tireless encourager to those who wanted to “engage culture” before that was a phrase, but he failed in some critical points in his analysis of the spirit of much modern art.

preached — Rookmaaker then told the story about his own love for the arts, even the very contemporary arts of his mid-twentieth century world. His book Modern Art and the Death of a Culture remains a very important work for many, many of my peers and heroes. I do recall, before understanding much of it (and understanding how much of it was misunderstood!) a college pal startling me by throwing it across the room. (You know who you are!) Alas, it ends up that Rookmaaker was a cultural and intellectual genius and a tireless encourager to those who wanted to “engage culture” before that was a phrase, but he failed in some critical points in his analysis of the spirit of much modern art.

See the difference in the title, his, and the new one? This newly released Modern Art and the Life of a Culture changes one word and it means by that to offer a fully different interpretive approach, shaped by a very different story and different sorts of research that has been done in the nearly fifty years since Rookmaaker first wrote. Bill Dyrness means no disrespect; he studied under Rookmaaker, in fact, and loved the man. But this is a book that needed to be written, in part so that a new generation of thoughtful Christian artists could grapple with the stuff Rookmaaker brought to us, and so that all of us could move past his errors or mis-readings.

To spell it out in detail would take me longer than you most likely would have patience for, here, but the oversimplified version is that Rookmaaker, as much as he loved modern art, jazz, and more, thought that contemporary art forms in the spirit of modernism were, perhaps trickling down from Romanticism, which reacted to Rationalism, basically were portraying a world bereft of meaning. He was understandably pessimistic about the “line of despair” as Schaeffer put it. Were the painters such as Bacon and the traumatized scream that was on the cover portraying wisely (through tears, even as his friend Francis Schaeffer put it) the loss of meaning in our existential time of crisis? Or were they evangelizing for that world, promoting a worldview that was nihilistic and ultimately harmful? Was it coincidence that a number of modern artists (Jackson Pollack?) took their own lives? How did atonal John Cage fit into that world? Does art reflect or shape culture? Is it fruitful to even explore the “ideas” or “message” of a painting or sculpture?

H. R. Rookmaaker wasn’t simplistically against modern art — it would be almost intentionally dishonest for anyone to say that — nor did he reduce art to merely conduits of ideas, but he exposed what he thought was the ethos of that world, the spirit of the times, captured in full color by Rothko and Dali and Warhol and Kandinsky and Hopper and Picasso.

For the record, one should know a bit about the assumptions and methodologies of Rookmaaker’s approach, the orbit in which he traveled, and the legacy of some of his students. There is a very impressive example of such found in the spectacular, lavish anthology, Art as Spiritual Perception: Essays in Honor of E. John Walford, edited by James Romaine, with a foreword by Hans Rookmaaker’s active, art historian daughter, Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker (Crossway; $40.00, which I reviewed here.) For a similarly impressive approach, drawing on similar Dutch philosophical roots, see this breathtaking collection of art history essays and articles by

For the record, one should know a bit about the assumptions and methodologies of Rookmaaker’s approach, the orbit in which he traveled, and the legacy of some of his students. There is a very impressive example of such found in the spectacular, lavish anthology, Art as Spiritual Perception: Essays in Honor of E. John Walford, edited by James Romaine, with a foreword by Hans Rookmaaker’s active, art historian daughter, Marleen Hengelaar-Rookmaaker (Crossway; $40.00, which I reviewed here.) For a similarly impressive approach, drawing on similar Dutch philosophical roots, see this breathtaking collection of art history essays and articles by  Calvin Seerveld, Art History Revisited (Dordt College Press; $20.00, which I announced, here.)

Calvin Seerveld, Art History Revisited (Dordt College Press; $20.00, which I announced, here.)

For a more accessible introduction to the life and work of Rookmaaker himself, see Art and the Christian Mind: The Life and Work of H.R. Rookmaaker by Laurel Gasque (Crossway; $16.99.)

We, by the way, have several of the major hardbacks in the Complete Works of Hans Rookmaaker left in stock. Write to us if you want to know more!

Despite the value of his evaluative approach, despite his prophetic warning about the loss of meaning amidst a secularizing modernity — is this were Guinness gets some of his fire for his cultural critique? — maybe something else is going on, and maybe Mr. Rookmaaker’s art historical method lead him somewhat astray. I think that many in this important world of Christian art historians, and those of us who read them, and the artists who take courage and inspiration from them will agree, it is time for a major reconsideration.

As Nicholas Wolterstorff puts it,

This is a book we have needed for a long time. The standard story of modern art is that it is the art of secularism and pervaded by nihilism. Anderson and Dyrness tell a very different story. Only those who refuse to read it can ever again think of modern art in the old way.

I await better reviews by those more qualified than myself; there have been other scholars and faith-based artists working on this for years, so I know there are others who will be taking this book very seriously. Dan Siedell has written importantly on this theme, offering his own critique of Rookmaaker and his heirs. See his very important God in the Gallery: A Christian Embrace of Modern Art (Baker; $25.00) and his 2015 collection of essays Who’s Afraid of Modern Art? (Cascade; $23.00.) Siedell wrote an afterword to Modern Art and the Life of a Culture called “So What?” which I actually read right away. Nicely done!

I await better reviews by those more qualified than myself; there have been other scholars and faith-based artists working on this for years, so I know there are others who will be taking this book very seriously. Dan Siedell has written importantly on this theme, offering his own critique of Rookmaaker and his heirs. See his very important God in the Gallery: A Christian Embrace of Modern Art (Baker; $25.00) and his 2015 collection of essays Who’s Afraid of Modern Art? (Cascade; $23.00.) Siedell wrote an afterword to Modern Art and the Life of a Culture called “So What?” which I actually read right away. Nicely done!

I am glad for much of the tone and approach of this book, as much as I’ve gleaned so far, at least. As associate professor of faith and culture at Trinity International University Taylor Worley says this is “more than a response to the original, Modern Art and the Life of a Culture is an invaluable companion to Rookmaaker.” It pushes back, yes, but it builds upon the major contribution that controversial 1970 volume made.

I also like that while Dyrness is a theologian and philosopher of culture (he has written widely in the arts) his co-author Jonathan Anderson is a practicing artist.

The introduction called “Religion and the Discourse of Modernism.” is remarkably interesting — a philosophically astute overview of many of the things many of us care deeply about currently — secularity and modernity, meaning and the common good, cultural engagement and more. Excellent.

The next major chapter is worth the price of the book to get a bit of the Rookmaaker bio, a survey of his most famous book and its strengths and weaknesses. I think anyone interested in the faith and art conversation these days needs to read it, and I am glad for their balance and grace throughout.

The rest of the book traces the history of modern art in the following chapters, under the rubric of “geographies, histories and encounters.” And there are encounters aplenty – even full color artwork:

Chapter 3 – France, Britain and the Sacramental Image

Chapter 4 – Germany, Holland and Northern Romantic Theology

Chapter 5 – Russian Icons, Dada Liturgies and Rumors of Nihilism

Chapter 6 – North America and the Expressive Image

Chapter 7 – North America in the Age of Mass-Media

This is a book that should be taken seriously. Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism is the first major release in highly anticipated new series by IVP Academic, “Studies in Theology and the Arts.

This is a book that should be taken seriously. Modern Art and the Life of a Culture: The Religious Impulses of Modernism is the first major release in highly anticipated new series by IVP Academic, “Studies in Theology and the Arts.

Their advisory board is a who’s who in this field, with the likes of Jeremy Begbie, Nic Wolterstorff, Linda Stratford, Judith Wolfe, Makoto Fujimura, Ben Quash and others.

The second volume is due in the Fall of 2016, entitled The Faithful Artist by Cameron J. Anderson, the current President of CIVA. You can pre-order it from us, also, of course, at a discounted price. Just use the secure order form link below.

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

10% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333