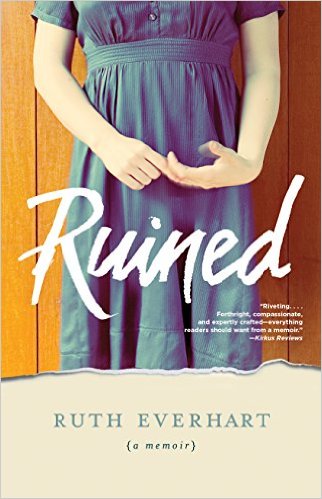

Ruined: A Memoir by Ruth Everhart (Tyndale House Publishers; $14.99.) Our sale price = $13.49

Ruined: A Memoir by Ruth Everhart (Tyndale House Publishers; $14.99.) Our sale price = $13.49

Our last Hearts & Minds BookNotes newsletter was well received and we are grateful for those who cared about the lovely, interesting, thoughtful work by Katelynn Beaty, A Woman’s Place. It is a rare sort of book that offers insight and stories, sprightly told, about not only the role of women in our culture – leaning in and daring greatly and all that – but does so within a nicely worked out view of vocation and calling. By bringing together these two topics, based on lots of interviews and astute observations about gender and work, Beaty, a gifted journalist, offers us a very great gift. It is highly recommended for men and women.

Ms. Beatty attended Calvin College in Grand Rapids Michigan. That she learned much about gender justice and the doctrine of Christ’s Lordship over all of life, lived out within the context of conversations about the imago dei, culture-making, and vocations in the work-world, while at that respected liberal arts college run by the Christian Reformed Church is notable; perhaps it is an indication of some things that have changed there in the last generations. It is true that their world-and-life view (as they used to call it, drawing from their heritage in the culturally-engaged public theology of Abraham Kuyper) has long emphasized forming the Christian mind for all-of-life-redeemed service for the common good, but, not that long ago, women were not central to that project. Like at most Christian colleges, the last decades have seen more women scholars with PhDs, more female students taking up philosophy or science or engineering, and a much more lively conversation on campus about gender, date rape, the problems with purity culture, and the like.

It was not always so.

I did not plan it this way, but the book I am eager to tell you about today begins at Calvin College, starting in one horrific weekend in early November 1978, when two young men from Grand Rapids raped four female students living together in an off campus house. As the riveting, occasionally gruesome, first 50 pages of Ruined: A Memoir describes, the young women were tied together, taken to the cellar floor, back again to their bedrooms, and terribly violated. Two of the women were raped twice, two only once, while another housemate was oddly spared.

I did not plan it this way, but the book I am eager to tell you about today begins at Calvin College, starting in one horrific weekend in early November 1978, when two young men from Grand Rapids raped four female students living together in an off campus house. As the riveting, occasionally gruesome, first 50 pages of Ruined: A Memoir describes, the young women were tied together, taken to the cellar floor, back again to their bedrooms, and terribly violated. Two of the women were raped twice, two only once, while another housemate was oddly spared.

Given the statistics of how many women are molested, raped, or abused in our society, it is nearly a certainty that you, as you are reading this, know women who have been assaulted; I feel a knot in my gut even as I type this, knowing this is true in my own circles. Even in our little Christian bookstore the small cards from a local rape crisis center offering assistance, which we have in the restroom, are routinely taken.

I am a bit surprised, actually, that we don’t sell more books about this topic. Like the upbeat Beaty book on work, Everhart’s Ruined is another book that I want to promote widely and press into the hands of many. It is illuminating about so very much, and a captivating story; hard as it is on several different levels, it is, truly, a good read. (The prestigious Kirkus Review said it has “everything readers should want from memoir.”) The crime, the aftermath, and the trial are the narrative center of the memoir, but it is – as most coming of age stories and spiritual memoirs – about so much more. At times I wanted to cheer, and at times I wiped away tears from my eyes.

Everhart is herself a respected Presbyterian (USA) pastor and a good writer. (We loved her previous book, a story of her travels through the Middle East, called Chasing the Divine in the Holy Land.) Her style is not flamboyant and her prose is sensible, solid, not at all purple, for which I was grateful. The book carries us along not on sheer brilliance of the dazzling language, but on the strength and integrity of the story.

And what a story it is. Any narrative of such horror and the quest to bring the perpetrators to justice is bound to be suspenseful and gripping, but what is also quite moving is her telling of her story of doubt, the struggle about God’s presence in the middle of the evil perpetrated, and her honest, logical rejection of simplistic language of God’s blessing. There is an understated scene that captures this: in their fear during the hours-long episodes they recited the Lord’s Prayer and the Twenty-third Psalm. Yeah though I walk through the shadow… Of course they cried out to God for protection. Weeks later in the school coffee shop where the victims gathered daily for support and to nurse their fears and anger, Ruth heard the roommate who was not sexually violated say that she was thankful God her heard prayers. Can you see how weird this kind of talk is: does that mean God did not hear the prayers of the other girls? Did God choose to spare the one but inflicted the evil upon the others, cowering in fear on the floor? Is God playing some game with human lives, doling out suffering here, helping some, hurting others? It’s a fair question.

(By the way, coming of age spiritual memoirs written by those trying to make sense of their lives are useful for all of us to read and sometimes useful to share with others, as a friend or road map or guide to the journey. I think of Faith and Other Flat Tires: Searching for God on the Rough Road of Doubt by the very fine writer Andrea Palpant Dilley which I reviewed a few years ago, also set on a conservative college campus, just for instance.)

(By the way, coming of age spiritual memoirs written by those trying to make sense of their lives are useful for all of us to read and sometimes useful to share with others, as a friend or road map or guide to the journey. I think of Faith and Other Flat Tires: Searching for God on the Rough Road of Doubt by the very fine writer Andrea Palpant Dilley which I reviewed a few years ago, also set on a conservative college campus, just for instance.)

This is the quandary of the ages, but it was particularly vexing for Ruth and the others there in Grand Rapids in the middle of the 20th century; God’s electing sovereignty is prominent in all Reformed theology but is perfected to a staggeringly systematic cornerstone among her branch of Dutch Calvinists – more so than in the writings of the famous Reformer himself, Ruth later suggests. But this was apparently the heart of the Sunday school and catechism and formation within the CRC and the girls had absorbed clichéd truism after clichéd truism with their mother’s milk: I have been a good girl, so things like this won’t happen to me. If God allows – sends? – such trouble, am I to be glad that He (always a He) is chastising me? Am I being punished? Are we to rejoice in all things No Matter What? Do not question these things.

Oh, how these toxic clichés hurt, oh how majestic and grand theological notions can be hardened into Slogans and Truths that do not match our lives lived East of Eden. Oh how selective some of our faith traditions (and some of our most vocal leaders) can be, citing this text, but not that one, telling this Bible story, but ignoring that one. Such theology becomes simple and firm and, while helpful to a few, necessarily unhelpful to most tender hearts or inquisitive minds. One major theme of Ruined is how this dogma from her CRC past was ruined for her. Bad advice, cheap slogans, failure to listen, refusal to host pain and doubt and lament, all plagued her (or at least this is how she tells the story.) The college was less than helpful – I am positive they handle such matters very differently now – and the Student Affairs staff and the chaplain himself were not helpful, let alone comforting and

wise.

Ruined tells well the story of the criminal investigation, the trial, the delays in the trial, how each victim – it took a while and some doses of empowering feminist theology to help them learn to describe themselves as survivors – responded to the publicity and the eventual indictments. Still, although this reads at times like a true crime story, it is mostly a faith journey. How does a young woman steeped in conservative evangelical and Reformed theology cope with a worldview crisis, when the things she assumed she believed no longer seemed to work? How do young women in the evangelical world remain in a denomination that (at that time) refused ordination to women? What social classes and associations and friendships can help a young woman come into her own? What kind of insights and churches allow such daughters of Sarah to flourish in the bosom of Abraham?

Another part of the story is explored carefully (although I would have wished for just a bit more, although it may not be my place to make such wishes known as it is her story to tell) is her struggle, in post-traumatic stress fashion, to be fair to African American men. Even though her assailants where a certain age and build, Ruth’s visceral response to black men was informed by what we now call triggers. At one point her rapist wiped a tear away from her cheek, showing even in the dark the pink of his palm. How does one untangle the maleness and the blackness of her assailants? She could not, she understood, hate all men. She could not, she also understood, hate all blacks. Her father, interestingly, worked as a principle of a very urban, multi-ethnic Christian school, so she grew up comfortable around folks of various socio-economic status and diverse races. Her coping with what felt to her like racist instincts after the attack as she continued to live in racially mixed neighborhoods is candid, raw, remarkable. (“My capacity for hatred bothered me,” she tersely writes. “I hadn’t known I was capable of such a thing. But I was.”) There were times nearer the end of the book that I had to put the book down just to ponder her experiences, rejoice in her honesty, glad for her desire for growth, wholeness, healing, justice.

Yet another part of this tremendous book is how Ruth’s faith journey led her to a new friend and an inner city Lutheran church community that indeed offered a safe place to grapple with theodicy, with questions about the role of women in society and church, to explore her love for philosophy and theology, kindled in spurts with good professors at Calvin. She attends an upstart seminary in a ramshackle building in Minneapolis, learning more about more mainline denominational voices, women’s theology, liberation theology, and more. She develops a sense of call into ordained ministry, blending her evangelical and Reformed heritage, her experiences in charismatic renewal, and her newly discovered contemporary theological skills with a keen pastoral sense. I needn’t tell you the rest, but it is always a delight, I think, to lean over the shoulder of one who is discerning a call, trying honestly (through a glass darkly, even, at times) to hear the voice of God and to pursue discipleship in a way that is coherent and faithful.

Yet another part of this tremendous book is how Ruth’s faith journey led her to a new friend and an inner city Lutheran church community that indeed offered a safe place to grapple with theodicy, with questions about the role of women in society and church, to explore her love for philosophy and theology, kindled in spurts with good professors at Calvin. She attends an upstart seminary in a ramshackle building in Minneapolis, learning more about more mainline denominational voices, women’s theology, liberation theology, and more. She develops a sense of call into ordained ministry, blending her evangelical and Reformed heritage, her experiences in charismatic renewal, and her newly discovered contemporary theological skills with a keen pastoral sense. I needn’t tell you the rest, but it is always a delight, I think, to lean over the shoulder of one who is discerning a call, trying honestly (through a glass darkly, even, at times) to hear the voice of God and to pursue discipleship in a way that is coherent and faithful.

I loved Everhart’s story at this point, even details about how she shared these new directions with her parents and extended Dutch family. These were painful days for the CRC and anyone whose faith has moved in somewhat different ways than one’s own beloved family will relate to her telling of her family dynamics.

How much of Everhart’s theological views of “divine mysteries” and sense of calling into the ministry came about because of the awful rape and the less than admirable response among many in her conservative Calvinist setting? Can this story that begins with an unspeakable act of violence – as the promo copy for the book says – “end with tremendous healing and profound spiritual insights about faith, forgiveness and the will of God”?

Yes, this is a story of coping with the aftermath of a rape. It is the story of struggling with the perennial questions “where is God when it hurts?” and “why is God silent?” and “why does God allow evil?” and “will I ever be whole again?” It is the story of doing theology, live, in real time, trying to make sense of one’s assumptions about faith, about what the Bible does and doesn’t say, about how to articulate in helpful ways stuff about faith, life, suffering, gender, justice and God’s will. This is a memoir about faith and about life.

And, I might say rather gladly for some of us, it is a snapshot into life in the decades of the 1970s and 80s. She mentions her fashion choices, and little details – bean bag chairs, listening to Gordon Lightfoot, the names of cars she drove, the phone booth wire coiled in steel – made me smile. That she mentions hangout spots in Grand Rapids was fun (we have good friends there, and a daughter who lived in Eastown where some of the book is set.) Her moving around the country – including a beautifully crafted episode of canoeing on Lake Superior where she meets (spoiler alert) her husband – rings true as she navigates her transition after college.

There is an epilogue to the book, set off in italics, that, even though only a few pages, have haunted me and touched me.

There is an epilogue to the book, set off in italics, that, even though only a few pages, have haunted me and touched me.

These pages are an open letter written to her daughters, one in college, one in high school. The girls apparently didn’t know that their mother was raped and their own response to this awful discovery was complicated. Her letter to them about being loved, about God’s grace, about possible hurt and trauma in life, was beautiful and poignant and powerful, the words incredibly moving. God will, she testifies, bring something new and beautiful out of the pain. You are loved no matter what. They are words I wish every parent could say to every child.

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

10% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333