We here at the bookstore are very excited about this book and I have been eager to tell you about it.

As always you can click on our button below to link to our secure order form page where you can order this on sale, or any other title you may want. Just tell us what your looking for and we’ll get back to you and confirm everything. Anything mentioned here is 20% off, too.

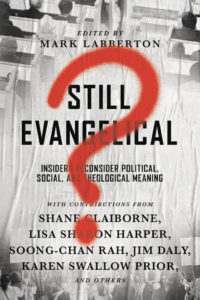

It is called Still Evangelical? Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning and is edited by Mark Labberton (IVP) regularly $17.00; our sale price = $13.60.)

It is called Still Evangelical? Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning and is edited by Mark Labberton (IVP) regularly $17.00; our sale price = $13.60.)

It seems to me that here are five audiences for this important book, five kinds of readers for whom I want to recommend it.

After an opening admittedly wordy rumination that I hope is helpful, I’ll quickly list the five kinds of readers who I think should order this book. And I am asking you to order it from us right away.

I’ll admit it is difficult to widely promote a book called Still Evangelical? I’m afraid half our readers won’t give it a chance so I’m asking you to hang in there with me. Some of you won’t like the question mark and others don’t like the word “evangelical.”

It’s tricky, too, because many don’t even know what the word means (including many in the religious media, and in many churches, too.) Many young adults raised in independent, non-denominational, evangelical churches don’t know that they themselves are “evangelicals” and don’t know that other churches are theologically and liturgically different. It’s weird, but I’m amazed at how mainline folks don’t know much about evangelical congregations and that evangelical folk have rarely experienced worship in a mainline church. So a book on this particular sub-culture is hard to explain (even though it is by far the largest sub-section within the Protestant church and doubtlessly the most important faith community within the North American religious landscape.) So I’ll try to explain a few things at the outset.

Maybe you are a theological progressive or fairly standard mainline church member – Lutheran, Episcopalian, UCC, United Methodist, PCUSA, RCA, and the like – and don’t think this book matters to you. I will suggest you are wrong, this book is urgent for you, too, and I’m sure you find it helpful.

Whether you are unfamiliar with the phrase or disinterested in it, I want to make the case that everyone should read this book. Roman Catholics, too, for that matter.

If you are a North American evangelical, whether you were born again at a non-denominational evangelistic rally or were led to Christ through Young Life, Youth for Christ, Cru, or CCO, or have had your heart strangely warmed at a United Methodist church camp or have come to affirm the classic, historic doctrines of theologically conservative denominations like the PCA or E Free or Southern Baptists, or maybe you attend one of the ubiquitous non-denominational community congregations or multi-site simulcast seeker churches, you most likely know who you are.

You most likely appreciate Max Lucado and Beth Moore and maybe R.C. Sproul or Ravi Zacheras; before he got too controversial, you liked Tony Campolo – man, could that guy preach. You have been involved in a small group Bible study you know about MOPS and maybe AWANA and your church uses the NIV or the ESV. Maybe you worry about the orthodoxy of outliers like Rachel Held Evans and Brian McLaren; you maybe know you are supposed to like C.S. Lewis but maybe haven’t read much of him; you like your daily devotional reading to be practical and lively and your terms of endearment with your Savior roll off your tongue easily. Your church is comfortable with talking about how God is real to you (and you might even call it “testimony.”) You desire to talk to your neighbor about Jesus and you know that His free, saving grace is the core of faith and gratitude for that can lead to passionate worship, whether in old hymns or contemporary praise and worship. You want to cling to the cross and you don’t mind saying so. You like it when sports stars give the credit to God and when movie stars give a shout out to their family values and to God’s blessings. You know people who send their kids to Christian day schools and you know people who go to Christian colleges. I’ll bet you’ve had a Compassion child, and you support any number of self-supporting missionaries; it’s what we do. You can’t imagine why anybody would mind the evangelism of Billy Graham or mind some of the good shows on Christian radio and you believe that walking with God day by day is the key to finding joy; again, you are eager to  share your own story of awakening to that truth. Maybe you don’t talk about getting “saved by the blood” but that’s really how you see it, just like in that song “The Wondrous Cross.” Once you were blind, but now you see.

share your own story of awakening to that truth. Maybe you don’t talk about getting “saved by the blood” but that’s really how you see it, just like in that song “The Wondrous Cross.” Once you were blind, but now you see.

Of course, more seriously, there are a lot of different sorts of evangelicalism and just like within other movements or denominations or ideologies, there are vigorous discussions and debates about what counts as true evangelicalism. One good debate back and forth is in the “Counterpoint” series and is called Four Views on The Spectrum of Evangelicalism edited by Andrew David Naselli and Collin Hansen (Zondervan; $16.99.)

For a look at a formerly evangelical theologian, ethicists and leader who has come to a Biblically-based social vision that is not conservative, and who has slowly left his own identity and self-identification as an evangelical, see the very moving memoir by my friend David Gushee. It’s called Still Christian: Following Jesus Out of Evangelicalism (Westminster/John Knox; $16.00) and is a very good read if you want a tender, moving religious memoir of a faith journey, and particularly if you want a glimpse of these sorts of issues and what one person came to believe about leaving his former affiliation (including his relationships with well known Southern Baptist conservatives) and taking up a new sense as a small church pastor and a professor at Mercer University.

For a look at a formerly evangelical theologian, ethicists and leader who has come to a Biblically-based social vision that is not conservative, and who has slowly left his own identity and self-identification as an evangelical, see the very moving memoir by my friend David Gushee. It’s called Still Christian: Following Jesus Out of Evangelicalism (Westminster/John Knox; $16.00) and is a very good read if you want a tender, moving religious memoir of a faith journey, and particularly if you want a glimpse of these sorts of issues and what one person came to believe about leaving his former affiliation (including his relationships with well known Southern Baptist conservatives) and taking up a new sense as a small church pastor and a professor at Mercer University.

EVANGELICALISM IS NOT THE SAME AS FUNDAMENTALISM

Evangelicalism in America is not the same as fundamentalism, though, and this is important, very important.

The God Hates Fags guy is not an evangelical, and neither are the name-it-and-claim-it Pentecostal prosperity preachers nor the “Jesus Only” heretics.

Many evangelicals are not tied to a literal six-day creation story and would rather talk about faith at Disney World than the oddball Creation Science museum in Kentucky. Evangelicalism was, in its earliest days, called neo-fundamentalism because they took the historic fundamentals seriously, but was a new thing, rejecting the sectarianism, literalism, anti-intellectualism, and right-wing nuttiness (“Kill a commie for Christ” Carl McIntyre used to say, and no hand-holding on campus, let alone inter-racial dating, Bob Jones used to say) that plagued those who proudly called themselves the “Fightin’ Fundies.”

Especially in the US South, I understand, the lines sort of blur between fundamentalists and evangelicals, but it is important that, by definition, evangelicalism is a movement and subculture that broke away from the anti-intellectualism and bigotry of fundamentalists.

Billy Graham helped pioneer that movement in the middle of the 20th century and it is helpful to recall that he was routinely protested by fundamentalists (they thought he was theologically too liberal and too willing to work with mainline churches and, yes, he stood quietly for racial integration. King himself appreciated Billy’s concerns and encouraged him to keep doing what he was doing, preaching the gospel to all, holding his inter-racial rallies.)

Yes it’s true: fundamentalists didn’t like Billy Graham because he was too liberal.

Billy was one of the founders of the flagship magazine of evangelicalism, Christianity Today, still what I’d say is the most important religious magazine in America.

Although CT has become much more politically and culturally progressive than it once was – they editorialized against Trump more profoundly that the mainline organ, The Christian Century, by the way – they remain mostly true to their theologically conservative and conventional founding vision. They encouraged social networks of likeminded missional types and started para-church ministries and publishing houses and Bible study programs and radio ministries and global relief organizations and rescue missions and church planting efforts and developed uniquely Christian scholarship at Christian colleges, energized by zeal learned from old-school preachers.

While in the middle and last half of the 20th century mainline church seminaries used books by authors like Rudolf Bultmann (who denied every key tenant of historic faith) and Paul Tillich (who called God the “ground of Being” and an “ultimate concern”) and Harvey Cox (who called us to embrace “the secular city”) and often faddish scholars who so critiqued the authority of the Bible that Biblical illiteracy and skepticism became a given in even the most successful Protestant churches, evangelicals were busy teaching Calvin and Luther and Wesley and heady scholars like Jonathan Edwards and Charles Hodge, alongside popular writers like C.S. Lewis and John Stott and Francis Schaeffer, preparing to figure out how to speak truth and grace into the rumblings of a postmodern culture coming apart at the seams. It is much more complicated than this, of course (as writers like Diana Butler Bass have documented) but it is generally true that mainline churches declined precipitously and evangelical churches took off almost everywhere.

From evangelicalism’s post-World War founders like Billy Graham and the socially engaged, moderate, Carl F.H. Henry, and the Presbyterian Harold Ockenga we ended up in 1976 with what Time magazine called “The Year of the Evangelical.” We had thoughtful, evangelical stars from Southern Baptist Sunday school teacher Jimmy Carter to the redeemed Chuck Colson working for prison reform to the racial-reconciliation leader John Perkins (himself with a third grade education, tortured by white cops, converted at an evangelical’s churches children’s ministry program, becoming a more evangelically-vivid civil rights leader) and a young quadriplegic best seller simply named Joni, who has gone on to be an inspiration, advocate for the disabled, and a thoughtful theological popularizer in her own right. Soon, we had intellectually respected scholars becoming better known, from world-renowned philosopher Alvin Plantinga to world-class geneticist Frances Collins to award-winning historian Mark Noll. From the (sadly now-defunct) Books & Culture to the brilliant Mars Hill Audio by former NPR correspondent Ken Meyers, we can see that evangelicalism is a faith tradition much more serious and thoughtful than the impression some have. With mostly men up front, and mostly white spokespeople, still, evangelicalism at its best has nonetheless been a thoughtful, middle ground between fundamentalists on the right who seemed disinterested in contextualizing the gospel in any way to the contemporary culture and modernist, liberal theology on the left that was largely accommodated to the increasingly secularized vales of the West.

ASIDE: (This is another story, but there are those that don’t fit the narrative of theologically conventional evangelicals who preached personal salvation and the inerrancy of the Bible vs mainline liberals who drifted from talk of personal salvation and fudged their view of the Bible. For instance, Mennonites and others in the Anabaptist tradition take the Bible and personal piety very, very seriously, but not in a way that was exactly evangelical. Latino and black gospel churches, Pentecostalism within established denominations like the Assembly of God, not to mention charismatic renewal happening within liturgical churches, and the Dutch neo-Calvinists in the reformational Kuyper tradition are all examples of those who were not theologically liberal, but were never quite at home in the Billy-Graham-Christian Today-National Religious Broadcasters/Christian Booksellers Association epicenter that shifted from the Wheaton College mid-West area to Colorado Springs.)

Evangelicalism gave rise to some of the most thoughtful, creative, and energetic para-church ministries we’ve seen in our lifetime, from the likes of the large and extraordinary World Vision International and Compassion International and the micro-financers Hope International to a network of fantastic liberal arts colleges like Calvin, Westmont, Eastern, Messiah, Seattle Pacific, Taylor, Gordon, Geneva, Asbury, Azusa Pacific and the like. Progressive theological pundits and secular media folks are just wrong to put, oh, say, Hope College or Kings in New York or Eastern University or Pepperdine University in the same category as fundamentalist Bible colleges. Again, evangelicalism is diverse and less odd and generally much more interesting than many know.

Evangelicals are behind profession-specific ministries like the intellectually fascinating Christian Legal Society and the aesthetically creative CIVA (Christians in the Visual Arts) and a host of think-tanks and work-world ministries like New York’s Center for Faith and Work or the Pittsburgh Leadership Foundation and remarkable scientific groups like BioLogos or The Colossians Forum. This energetic evangelical movement has given rise to the world’s leading voice against sexual trafficking (International Justice Mission) and a little conference in Pittsburgh that has in some ways connected with many of the above organizations called Jubilee.

Evangelicals use of mass media in the 20th century was second to none and their missionary impulse was historic, to put it mildly. Their great passion for sharing the gospel and reaching the nations compelled them to excel in communications, Bible translations, missionary endeavors, literature distribution, educational outreaches, including camps and camp meetings, and more disciple-making programs than you can count. It is no surprise that there was a huge rise in Christian publishing and mostly conservative evangelical bookstores in the last decades of the 20th century. Our ecumenicism was confusing to many in our early years because evangelical faith so clearly dominated the religious publishing world; it confuses folks today, still, as liturgical and mainline Protestant stores have one by one by one closed their doors.

When one thinks of evangelicalism we can think of altar calls and Focus on the Family and Amy Grant being criticized for “crossing over” to mainstream music. We know about bad inspirational art and cheap inspirational romances novels with happy conversion stories always included and cheesy rapture bumper stickers. And — the context for Still Evangelical? Insiders Reconsider, of course — eventually evangelical faith in some quarters got mixed up with right wing politics and, now, with alt-right politics and Trumpism. That story has been told elsewhere, but now, one year after the Trump inauguration, this is a huge factor in the perception of the credibility of evangelicalism as a movement and the gospel itself.

But despite the right wing take-over (or the perception of such a take-over, which I think is over-stated) we should also think of the important history of how 19th century evangelists signed people up for the abolitionist cause, how evangelical colleges were among the first to enroll women, about the lively evangelical faith that caused many to give their lives to the poor and the destitute, including revivalists like D.L. Moody. We can think of Young Life volunteers leading lost kids – from suburban high schools and inner city ghettos – to know Jesus in their zany meetings and fabulously fun camps.

We should think of a number of important women like Dr. Shirley Mullen and Dr. Kim Phipps, to name just two, who are Presidents of evangelical colleges who are mentoring a new generation of women leaders who are firm in historic faith and stepping into roles of Christian leadership all over the land. Some evangelicals have been advancing Biblical feminism for years.

And we should consider Christian converts like Mako Fujimura, who is now one of the esteemed abstract artists of our time and young author Michael Ware who was one of the youngest staffers to have worked in the White House (and who wrote the fascinating Reclaiming Hope: Lessons Learned in the Obama White House About the Future of Faith in America.) We can think of modern sociologist Os Guinness talking about civility when he worked at The Brookings Institution and how one of the best known contemporary evangelicals, PCA pastor Timothy Keller, is hosting Pulitzer Prize novelist and public intellectual Marilyn Robinson in Manhattan next month. As I said here a few weeks ago, it is the decidedly evangelical InterVarsity Press that has published the most faith-based books on racism in the last 40 years, and the evangelical Christian Community Development Association (CCDA) is by far the most energetic and wide-spread faith-based community development organization working today, who have been for decades nurturing a generation of savvy urban activists that can organize like ACORN and preach like the most fiery of old-school evangelists.

The very best theological discourse in some urban centers is led by people of color who identify as evangelical. The “Fellows” program is nurturing sophisticated next-generation leadership for the common good in most major cities in the US, reading together curriculum as diverse as Wendell Berry and John Stott, Tim Keller and Steve Garber along with poetry by Luci Shaw and the hip hop poetry by Grammy-award winning rapper Lecrae and the brilliant spoken word artist Propaganda. Neighborhood Bible studies and work-world prayer meetings and one-on-one mentoring to make disciples have influenced literally millions of folks who can talk with clarity about their own personal faith in God, the relevance of the Bible for their own daily discipleship, and how their church (or para-church ministry) has helped them learn how to live a vibrant Christian life. Even though this is sometimes seen as a bit simplistic or clichéd, there is no doubt that evangelical ministries have had a wonderfully life-giving and transformative influence that has born beautiful fruit in a way that no other church movement has in our time.

RAPPROCHMENT

In our generation we have seen an interesting rapprochement between evangelicals who have become more open and engaged in mainline institutions and churches and (on the other hand) mainline folks who have become more appreciative of evangelical piety. (It used to be that in many denominations if one graduated from an evangelical seminary – such as Gordon Conwell, that by nearly all accounts is more rigorous than their nearby consortium members Harvard Divinity School, say – it was very hard to get a ministerial call, as mainliners distrusted evangelicals as pastors, but that is changing.)

Young evangelicals are now teaching at mainline seminaries; until his death of cancer, former IVCF leader Dr. Stephen Hayner was the President of PCUSA Columbia Theological Seminary in Decatur, Georgia and places like Gordon Conwell and Fuller Theological Seminary routinely read UCC scholar Walter Brueggemann; one of his recent books, Journey to the Common Good, were lectures delivered at Regent College in British Columbia, a place where Puritan scholar J. I. Packer taught.

Some evangelicals for thoughtful reasons are classic conservatives and identify with the religious right and some, like, say, Ron Sider, and, I suspect, Tim Keller, are Democrats or Independents. Most evangelicals cheer for the balanced leadership on social issues offered by the clearly gospel-centered and non-partisan Russell Moore within the Southern Baptists (illustrated in his book Onward: Engaging the Culture without Losing the Gospel) and many mainline denominational leaders draw on the evangelically-influenced spiritual direction training of Richard Foster’s Renovare or the well-loved Transforming Center run by former Willow Creek spiritual director Ruth Haley Barton.

It was evangelical Richard Foster, after all, who introduced many Protestants to the medieval mystics and the monastic practices of meditation and lectio devina. I swear there are more evangelicals doing Ignatian spiritual examen these days then Jesuits! Mainline liberals, especially, love the contemplative Richard Rohr who, as most know, found his own faith deeply impacted in the 1970s by the evangelically-influenced charismatic renewal. All of this is to suggest that the old days of liberals and evangelicals disavowing each other are waning.

DON’T BUY IT

So, I say: when the media talks about how many white evangelicals are far-right Trump nuts, don’t buy it. Maybe a lot of fundamentalists and unusual Pentecostals supported him, but few in the mainstream evangelical world resonate with his message or style. Evangelicalism – centered around evangelistic ministries like Youth for Christ or The Salvation Army or Christian Colleges like Wheaton or magazines like CT or World and church renewal networks like The Gospel Coalition or Alpha and prayer ministries and disciple-making agencies and the huge Urbana Missions Conference or Passion conferences or Q Ideas gatherings – do not see themselves working to Make America Great Again.

Evangelicals, by definition, are people who grew up singing “To God Be The Glory” and “Shine Jesus Shine” and asking “What Would Jesus Do?” Sure many have watched the horrid “Left Behind” movies, but many roll their eyes, and are drawn to the likes of Amazing Grace the powerfully evangelical film about William Wilberforce and his campaign to stop slavery in England. There is a renewed interested in recent years in Dietrich Bonhoeffer, even, because of Eric Metaxas’s telling of Bonheoffer’s deeply religious transformation as he was inspired by the gospel preaching and singing at a black church during his time in New York.

As Jim Daly – who became the theological and culturally conservative head of Focus on the Family after Dr. Dobson left – shares in Still Evangelical? he felt compelled to reach out to one of the leading LGTBQ activists, despite their disagreements about sexual ethics and public policy, and was delighted that this understandably wary gay leader responded in what became a friendship based on a search for common ground. Granted, Daly lost some supporters and friends over this outreach, but it’s a new day within evangelicalism when that kind of conversation happens and those kinds of friendships form.

Q Ideas leader Gabe Lyon, author of The Next Christians and, more recently, co-author of Good Faith (who hosted the two gentleman in one of his Q Ideas conferences, by the way) sees this stuff all the time, fresh and creative projects initiated by evangelicals building partnerships with others in ways that wouldn’t have happen a few decades ago.

Still, despite all this, and my own insistence that evangelicalism does not equal fundamentalism, the media has widely, widely reported that the disastrous rise of the alt-right and the Trump administration has been significantly supported by the majority of evangelicals.

Which has caused a flurry of introspection and bunches of folks saying they are done with evangelical Christianity. Some have said they can no longer stomach the Christian faith at all. The gospel message as undoubtedly been confused and comprised these past few years and evangelicalism has, at best, a PR problem.

So.

All of that to say that if you think you have evangelicals pegged as right-wing fundamentalists like Falwell or heretics like Pat Robertson or the duped ladies campaigning for Roy Moore with their garish God Bless America outfits, you need to read this book.

Still Evangelical? Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning shows the theological, ethnic, and wide cultural variety of evangelical thought leaders – from pacifist urban activist and Red Letter Christian Shane Claiborne to Focus on the Family’s Jim Daly, from evangelical seminary profs like Mark Young of Denver Seminary to CT editor and ordained PCUSA pastor Mark Galli, from evangelical Christian college profs like Allen Yeh from Biola University to literary figure, writer and professor Karen Swallow Prior, who teaches at Falwell’s Liberty University.

Still Evangelical? Insiders Reconsider Political, Social, and Theological Meaning shows the theological, ethnic, and wide cultural variety of evangelical thought leaders – from pacifist urban activist and Red Letter Christian Shane Claiborne to Focus on the Family’s Jim Daly, from evangelical seminary profs like Mark Young of Denver Seminary to CT editor and ordained PCUSA pastor Mark Galli, from evangelical Christian college profs like Allen Yeh from Biola University to literary figure, writer and professor Karen Swallow Prior, who teaches at Falwell’s Liberty University.

Karen’s wonderful chapter is quintessentially evangelical – it is very thoughtful, very well written, and a lovely blend of personal narrative (giving testimony is in the DNA of any true evangelical) and social analysis. It is strong on theological essentials and attentive to the nuances and diversity of how others see things. Fundamentalists of various sorts – of the right or the left, I might add – are dogmatic and often stern. Karen’s story and contribution to Still Evangelical? is upbeat about the gospel, clear about her own story, and eager to ruminate helpfully about the strengths and weakness of her own inherited faith tradition. Can we save evangelicalism? Should we? How does she navigate her own evangelical commitments in a place like Liberty? Her chapter “Why I Am An Evangelical” is simply must reading for those that want a delightful glimpse into the best of evangelical writers these days.

Another quintessential narrative that I really, really enjoyed is the piece by Lisa Sharon Harper, in her chapter called “Will Evangelicalism Surrender?” This chapter is very strong and in some ways it is the most clear about the experience of growing up within evangelicalism. Lisa tells of her heart-felt and tear-stained walk down a sawdust trail at a camp meeting where she received Christ as her Savior and found herself, as a black girl, involved in the mostly white evangelical sub-culture in rural South Jersey. Those that know Sharon know of her journey as a woman leader within the evangelical campus ministry IVCF and her fight for an evangelical vision for racial justice and social righteousness. (She contributed the “left” part of the helpful back-and-forth book Left, Right, and Christ: Evangelical Faith in Politics co-written with Orthodox Presbyterian pastor and thinker D.C. Innes.)

It made sense that Ms Harper ended up at the ecumenical Sojourners that, although appreciated by mainline liberal activists and social-justice-minded nuns is still animated by an evangelical zeal from their earliest days when they were kicked out of Trinity Evangelical Divinity School for organizing campus anti-Viet Nam protests. Jim Wallis, their founder, was part of the Plymouth Brethren denomination, a classic evangelical denomination with a strict, holiness ethos and serious Bible teaching and he still preaches in the style of an evangelical.

I cannot imagine how Sharon emotionally holds up as a self-professed evangelical, since she is also a vivacious, radical activist – she’s been arrested in anti-poverty sit-ins, travelled in the third world with African liberationists, preached on the streets at anti-war marches, and fasted in front of the Capitol for immigrants, and counseled young Black Lives Matters activists; she captures and embodies the early vibe and lifestyles of mid-70s Jim Wallis and Sojourners more than anybody I’ve seen in decades. Like Shane Claiborne, Lisa Sharon Harper is a new century version of the folks described in the University of Pennsylvania Press volume, Moral Minority The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism by David Swartz combining heart-felt evangelical piety and Bible teaching with this radical social vision. She loves telling her story of what Jesus means to her, she loves talking about his amazing grace and the power of the Bible to point us to the Kingdom of God where we can know forgiveness and meaning and be restored and reconciled to God, self, others, and the land itself. Her book The Very Good Gospel: How Everything Wrong Can Be Made Right (published by evangelical publisher Waterbook Press) explores this stuff well, giving the phrase “gospel centered” a very socially-relevant meaning and embodied expression. Again, her chapter here in Still Evangelical? is well worth pondering. It is hard hitting but tells her story nicely. Kudos!

So, if one wants to know a bit about evangelicalism, these sorts of testimonials are a good place to start.

Other chapters in this book do a very good job in telling the historical/sociological story that I only quickly rushed through above. (Admittedly, too, I told it a certain way, to accentuate my concern that we don’t conflate all religious conservatives together into one big bunch.) Several of the other chapters in this nice volume are wonderful overviews of the missional distinctives of evangelicalism and how that has or hasn’t (re)shaped evangelicals engagement in the world. I loved these brief, historical/sociological essays and appreciated their insight in connecting stuff of the past with stuff going on today. I think it’s a great window into understanding not only our work here at Hearts & Minds but much of what has gone on in the broader religious communities in recent decades.

FIVE SORT OF READERS

I will be brief in naming five sorts of readers who should study this.

First, again, it is for anyone who wants to know what we mean by evangelicalism. There are other more scholarly explorations of what this often-mentioned religious movement in the US is, and what the word means, but these chapters get at it wonderfully, and it’s a great intro to the largest Protestant movement in the country. I really, really hope that Episcopalians and Lutherans and UCC and Catholic and Methodist friends buy this book and study it together in their parishes. It’s that good.

Secondly, this is a must-read for evangelicals themselves, especially anyone in leadership or who is older. It is essential to own and study Still Evangelical? if one is on the more conservative end of the spectrum; reading and pondering this mix of authors asking how to navigate the changing world and how to hold true to our deepest convictions – keeping the first things first, as we sometimes put it – is vital. If you wonder what the fuss is about, if you don’t quite understand why younger folks, especially, are leaving evangelical churches, or why many aren’t so sure they want to use this phrase about themselves any more, then you have to get this book right away. If you have any desire to keep conservative theological views alive and well and keep our beloved evangelical tradition healthy, we have to grapple with this stuff within our own circles. Just for instance, Soong-Chan Rah’s piece on “Evangelical Futures” is a lively, short summary of his major work and it might inspire you to read his other vital books. It’s important for all of us, but especially conventional evangelicals who are fretting about the changes spinning around them.

Thirdly, if you are a social activist of any sort, you know that many of the people on the streets are motivated by faith, even if they feel a bit exiled from their old churches. Those resisting Trump’s draconian immigration attitudes or racist tweets or his cavalier attitude about sexual abuse or his dishonesty on economics or his despicable policies rolling back stewardly care for creation or his frightening nonsense about the size of his nuclear button, are often former evangelicals or somehow motivated by values learned in Sunday school. Some say they are “spiritual but not religious” and some say they are “recovering evangelicals” and some aren’t Christ-followers but they can quote Martin Luther King and Desmond Tutu and other Christians. I think this book might be a life-line to those who have drifted away from church, or are tempted to jettison clear-headed, Biblically-solid, theologically-sound, spiritually-faithful sorts of faith.

There are other books that link evangelical faith and progressive social action, and there are books that tend to abandon evangelicalism for more progressive but still robust sorts of faith, so there are no shortage of resources to build bridges with activists who need reminded of God’s call and the significance of church life, but this up-front conversation about what we can reasonably expect of evangelicalism might be just interesting enough to reach some, to help engage them in good conversations. (See, I’m an evangelical myself so I think in terms of “reaching” people groups, like, in this case, left-wing, anti-Trump activists who have soured on church because they think that evangelicalism is bigoted and retrograde, not worthy of deep consideration.) These good, balanced, chapters in Still Evangelical? while not firstly apologetics, could be helpful witnesses to a faith tradition that they have mostly not given up on. I’d love to see it shared with some of those we learned about in the Barna research that became the book by Barna guy David Kinnaman, You Lost Me: Why Young Christians Are Leaving Church . . . and Rethinking Faith. Or for those who are so vividly portrayed in the book Rescuing Jesus: How People of Color, Women, and Queer Christians Are Reclaiming Evangelicalism reported vividly by former evangelical Deborah Jian Lee. I firmly believe that some who are most critical of evangelicalism need to listen in to this self-aware and candid conversation among evangelical insiders; it isn’t as self-critical or radical as it might be as these authors really are mostly very invested in the evangelical sub-culture and have a palpable love for Christ and his good news. It just might restore their faith or at least remove some of the cynicism and bitterness if they give it a chance. Maybe you know somebody you could give it to.

Fourthly, I think this is a great book for anyone who likes to keep an open mind by pondering what different people think, holding together reasonable insights that sometimes might be in tension. You could obviously pick other books on other topics to learn about this process of good learning, of dialogue and conversation, but this one is as hot as any in religious circles, even among non-Christians, as we consider the way in which religion has played a role in our national politics.

Still Evangelical? Ten Insiders Reconsider… would be even more useful if there was some push-back and responses from each of the authors back and forth rather than just being a collection of random essays, but, still, the fact that this includes authors representing “right, left, and center” within broad evangelicalism is itself just a great example of a somewhat diverse conversation. There are fairly young evangelicals and older ones and a good number of people of color, women and men, those who are more on the fringe of classic evangelicalism and those who – like Jim Daly, of Focus on the Family — are at the very center of it. That the President of the large InterVarsity Christian Fellowship college ministry (Tom Lin) is here talking about the next generation of Christ followers (and his hope that they remain firmly evangelical) is notable.

It is great that the book was envisioned and edited by Mark Labberton, the President of the world’s most multi-ethnic and multi-national seminary (Fuller Theological Seminary) who is both a PCUSA clergyman and a respected evangelical who has written about worship and evangelism and justice and discipleship. I would have wished for Reformed thinker Richard Mouw’s wise and civil voice in here – his wonderful memoir published a year ago is called Adventures in Evangelical Civility: A Lifelong Quest for Common Ground and it is utterly germane. I’d have also wished for a non-evangelical like a liberal Lutheran or progressive United Methodist or standard Episcopalian reply to all of this. Still, it’s got a lot of different views and some varying answers to this question.

Should we retain the name, or re-brand ourselves? Can we remain faithful to Jesus and the gospel and be affiliated with this odd movement which seems to have been co-opted by a unethical religiosity in support of a terrible man with disturbing political plans? These evangelical leaders and “insiders” have varying levels of concern and different sorts of answers to this provocative question and it is urgent to answer this question, as I’ve suggested, but it is also just good to see how good people can disagree somewhat. I don’t think anyone can disagree that the religious right’s support of the playboy Trump is odd at best. What we should do about the PR crisis this has created and the faith-crisis that is growing in our evangelical ranks is a live question, so it’s good to see a bunch of different folks weighing in.

This isn’t a book about conflict resolution or civility, but it’s good to have such reasonable, thoughtful voices in the same book. Why not read it, gentle readers, just to be reminded of the practice of listening well and keeping an open mind. In our deeply polarized age, this is a breath of fresh air.

Fifth. This is simple, and I am sincere in saying this. Regardless of your theological and denominational affiliations, it is refreshing (and, more — vital) to be reminded just what we should be about. I guess I think that at our very best, we all agree on this stuff – we are all trying to respond well to God’s love that is seen in the person of Jesus. We all want to recall the grace and goodness of the gospel, right? We all want to build churches and ministries and communities that embody God’s goodness, as best we can, don’t we? We want to live a better story. Most of the writers in this book – even though they differ considerably – agree that no matter what we call ourselves or in what ways social, religious, and media forces confuse theological terms and meanings before the watching world, we are to focus on the truest truths about what matters most.

As Mark Young puts it in his good chapter “Recapturing Evangelical Identity and Mission”,

To the degree that evangelicalism continues to define itself by anything other than the gospel, answering my friends question [about why I am an evangelical] will remain problematic for those of us who care about how the broader culture hears the gospel. If we are not radically and persistently intentional about defining evangelicalism in terms of the gospel, I see no reason to continue to use a label that now misrepresents our true identity and it counterproductive to our calling…

Or, as Mark Labberton himself puts it in his lengthy introduction, after surveying everything from the recent waning of denominational loyalties to the crisis of rural and Rust Belt congregations to the plight of those in the LGBTQ communities, and more, when he clarifies what’s finally at stake:

Evangelical has value only if it names our commitment to seek and to demonstrate the heart and mind of God in Jesus Christ, who is the evangel. To be evangelical is to respond to God’s call to deeper faith and greater humility…. the only evangelicalism worthy of its name must be one that both faithfully points to and mirrors Jesus Christ.

Labberton quips that maybe the question isn’t “still evangelical?” but “yet evangelical?”

This is the question for all of us, isn’t it? This book will remind us of this large looming question. I highly recommend it.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% Off

order here

this takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown PA 17313

read@heartsandmindsbooks.com

717-246-3333