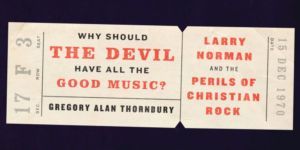

SPECIAL OFFER – ONE FREE MARK HEARD CD WITH PURCHASE OF Why Should the Devil Have All the God Music? Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock regularly $26.00 – BookNotes special 20% OFF (our price $20.80) + free Mark Heard CD while supplies last, limited time only.

FREE CD OFFER ENDS SUNDAY MARCH 24, 2018

or until supplies run out

I am going to try to keep this relatively brief, in part because I don’t want to get overly emotional in reporting about this new book that means so much to me that streets today, a careful, thoughtful, and detailed biography of the “father of Christian rock” Larry Norman written by Gregory Alan Thornbury. But it will be hard as there’s so much that reading this book reminded me of and so many reasons to enjoy reading it. We are thrilled to be selling it now, as it releases today.

Why Should the Devil Have All the God Music? Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock is a fabulously interesting book and, like the best rock and roll biographies – among my personal favorites include Testimony by Robbie Robertson of The Band and the splendid Fire and Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY, and the Lost Story of 1970 and the must-read Beatle’s study by Larry Norman’s friend, Steve Turner, called Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year – it includes lots of stuff about music and song lyrics and production of albums and rock tour stories, but also fair amount of fun celebrity gossip and, thank goodness, some social and cultural and religious commentary. How can one reflect on an artist who hung out with The Jefferson Airplane and opened for Jimi Hendrix and chatted with Paul McCartney and sang about racism and poverty and against the rootlessness of a materialistic generation not explain a bit about the ethos of the 1960s? Norman came of age, and gave voice to Christian faith amidst the California counter-culture; his art was a loud and often-controversial critique of bad religion and boring church and it stood (at least in the early days) as part of the broader zeitgeist which critiqued the bankrupt values of the American dream and the sins of the American empire.

Why Should the Devil Have All the God Music? Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock is a fabulously interesting book and, like the best rock and roll biographies – among my personal favorites include Testimony by Robbie Robertson of The Band and the splendid Fire and Rain: The Beatles, Simon & Garfunkel, James Taylor, CSNY, and the Lost Story of 1970 and the must-read Beatle’s study by Larry Norman’s friend, Steve Turner, called Beatles ’66: The Revolutionary Year – it includes lots of stuff about music and song lyrics and production of albums and rock tour stories, but also fair amount of fun celebrity gossip and, thank goodness, some social and cultural and religious commentary. How can one reflect on an artist who hung out with The Jefferson Airplane and opened for Jimi Hendrix and chatted with Paul McCartney and sang about racism and poverty and against the rootlessness of a materialistic generation not explain a bit about the ethos of the 1960s? Norman came of age, and gave voice to Christian faith amidst the California counter-culture; his art was a loud and often-controversial critique of bad religion and boring church and it stood (at least in the early days) as part of the broader zeitgeist which critiqued the bankrupt values of the American dream and the sins of the American empire.

The talented and very interesting Dr. Thronbury is well suited to this big task and he does it well. I do not think Dr. Thornbury – a young, bow-tied scholar (and an obviously thoughtful and appreciative Norman fan) – spent enough time in the otherwise excellent book reflecting deeply on this early era, and it may be because he wasn’t there and couldn’t conjure enough of the pathos and dislocations of those days. Those of us who remember the day King was killed,  who feared the riots and the KKK and the guns of the Panthers and the Symbionese Liberation Army, those of us who participated in early Earth Day activities, who marched against the war, who wept at the napalm used in Viet Nam, who grew cynical from Watergate and wondered why our churches seemed less interested in these hugely ethical and spiritual matters in our culture than they should have been, found in Larry’s music a Christian who seemed to understand us. Yes, those of us who listened to Dylan and Simon and Garfunkle and yelled out the chorus of “Four Dead in Ohio” as a lament, we needed the Jesus-drenched lines of Norman, too, and I wished the deep, deep pathos of that longing for relevant Jesus rock came through more in this book. In those days, Larry was the closest thing we had and thinking about it still conjures for me dread and joy and passion and frustration and hope.

who feared the riots and the KKK and the guns of the Panthers and the Symbionese Liberation Army, those of us who participated in early Earth Day activities, who marched against the war, who wept at the napalm used in Viet Nam, who grew cynical from Watergate and wondered why our churches seemed less interested in these hugely ethical and spiritual matters in our culture than they should have been, found in Larry’s music a Christian who seemed to understand us. Yes, those of us who listened to Dylan and Simon and Garfunkle and yelled out the chorus of “Four Dead in Ohio” as a lament, we needed the Jesus-drenched lines of Norman, too, and I wished the deep, deep pathos of that longing for relevant Jesus rock came through more in this book. In those days, Larry was the closest thing we had and thinking about it still conjures for me dread and joy and passion and frustration and hope.

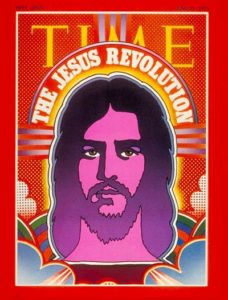

But, still, Why Should the Devil… gives us the very best study yet of the odd Christian folkie-rocker and One Way leader and it is nothing short of a must-read for anyone interested in rock music of the 60s & 70s and onward, how the Jesus Movement emerged from the hippy counter-culture, and how this gave rise, oddly – yep, this is true — to the rise of the Christian right in the 1980s and 90s. If you care about issues of “Christ and culture” as we say, this is an important report from the backstory. In that sense, as we try to figure out these odd religious days, this is an important part of the puzzle.

Less grandiose and perhaps more fun, if you’ve ever enjoyed cool Christian rock – think Mark Heard or Keaggy or Charlie Peacock or the 77s or Sam Phillips or the best work of Amy Grant or VOL or POD or Gungor or Lecrae or Switchfoot or Sara Groves or Jennifer Knapp or Crowder – you know that you owe it to yourself to learn a bit more about the grand-daddy of all this.

Less grandiose and perhaps more fun, if you’ve ever enjoyed cool Christian rock – think Mark Heard or Keaggy or Charlie Peacock or the 77s or Sam Phillips or the best work of Amy Grant or VOL or POD or Gungor or Lecrae or Switchfoot or Sara Groves or Jennifer Knapp or Crowder – you know that you owe it to yourself to learn a bit more about the grand-daddy of all this.

And, if you’ve ever lamented the cheesy and shallow end of Christian rock, from bad album covers to goofy lyrics to sub-par production to crass commercialization, well, Norman was both an alternative to that (with his manifestos about art, his admiration of Francis Schaeffer, his hopes for artist collectives, and the hope of making mainstream, artful witness in the real entertainment world) and, yes, also, in many ironic ways helped set into place the industry that caused so much dumbing down and commercialization of the CCM subculture. That Thornbury’s book has the subtitle Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock is, in part, a very big nod to this very big quandary.

It is a true biography and less a study of the movement that Larry Norman was a part of, but it explores and reflects on much that is important, that was generative and influential; I believe it would have been an even stronger book if Thornbury had cited seminal works about the way in which rock music had within it the tensions of art and commercialism. If he had explored and reflected more on the meaning and social implications of the details he shares – fascinating ones like how Pat Boone funded early Norman records and how Norman protégé Randy Stonehill had legal battles with producers in England and why agents and DJs and critics – not to mention fans – loved Norman but his record sales were marginal and why we ended up with Christian bookstores that carried gospel music in a way Tower Records didn’t, and so forth. And why-oh-why Christian followers, especially, were confused (and some, outraged) by his less overtly religious recordings (see the great chapter on So Long Ago in the Garden, for instance.) The promo for the book notes that this previously untold story is set “at the dawn of the culture wars” and that is a helpful reminder of the big picture this is about.

It is a true biography and less a study of the movement that Larry Norman was a part of, but it explores and reflects on much that is important, that was generative and influential; I believe it would have been an even stronger book if Thornbury had cited seminal works about the way in which rock music had within it the tensions of art and commercialism. If he had explored and reflected more on the meaning and social implications of the details he shares – fascinating ones like how Pat Boone funded early Norman records and how Norman protégé Randy Stonehill had legal battles with producers in England and why agents and DJs and critics – not to mention fans – loved Norman but his record sales were marginal and why we ended up with Christian bookstores that carried gospel music in a way Tower Records didn’t, and so forth. And why-oh-why Christian followers, especially, were confused (and some, outraged) by his less overtly religious recordings (see the great chapter on So Long Ago in the Garden, for instance.) The promo for the book notes that this previously untold story is set “at the dawn of the culture wars” and that is a helpful reminder of the big picture this is about.

Thornbury doesn’t preach, and allows the story to develop, but I still wished for a bit more of his scholarly expertise. For starters, then, I commend two must-reads: the serious Christian scholarship of Pop Culture Wars: Religion & the Role of Entertainment in American Life by William David Romanowski (Wipf & Stock; $45.00) and the rowdy, must-read The Day Alternative Music Died: Dylan, Zeppelin, Punk, Glam, Alt, Majors, Indies, and the Struggle Between Art and Money for the Soul of Rock by Adam Caress (New Troy Books; $16.99.)

Larry Norman’s good friend Steve Turner, the rock critic from England, is helpful, too, while we’re at it, in framing a larger picture of Christians engaged in the arts and popular culture – see his very nicely done Imagine: A Vision for Christians in the Arts (IVP; $19.00) or, for those engaged in contemporary performance art, see the soon-to-be-released brilliant anthology It Was Good: Performance Art to the Glory of God edited by Ned Bustard (Square Halo Books.; $19.99.)

Fortunately, geeky Greg Thornbury (now serving at the New York Academy of Art) is very aware of these aesthetic and cultural concerns and has spent years ruminating and writing on them – what does it mean to be “in the world but not of it”? How do Christians serve as “salt and light” within the arts and popular culture? What is the role of God’s people to shape and influence cultural trends? How should we think about these things well? Although I may have wished for a bit more direct comment about all this, it is there between the lines, and in some of the footnotes, making Thornbury a very, very appropriate and helpful teller of this big tale. And what a tale it is.

Fortunately, geeky Greg Thornbury (now serving at the New York Academy of Art) is very aware of these aesthetic and cultural concerns and has spent years ruminating and writing on them – what does it mean to be “in the world but not of it”? How do Christians serve as “salt and light” within the arts and popular culture? What is the role of God’s people to shape and influence cultural trends? How should we think about these things well? Although I may have wished for a bit more direct comment about all this, it is there between the lines, and in some of the footnotes, making Thornbury a very, very appropriate and helpful teller of this big tale. And what a tale it is.

Larry Norman was conflicted, odd, artful, beautiful, serious, funny, perhaps dishonest, perhaps narcissistic, and more. Why Should The Devil doesn’t shy away from explaining his multi-dimensional and complicated personality, his brokenness, his genius. Many who knew him both loved and hated him, and those that like his music – or at least many of us – hold him in high regard, but still wished for more from him. He was a genius, but operating, some think, within the constraints of a conservative church and a quirky theology and at the nexus of the counterculture and the emergence of the new youthful, rock and rock culture. That his huge project of being a Christian in but not of that sub-culture became in many ways exactly opposite – of but not in the world – is a supreme irony. (Read that sentence again.)

This vivid new biography is an important telling of the story of this remarkable character and his remarkable life but it is also a chronicle of so much that has happened for many of us.

This stuff means a lot to me and I trust it means much to many of our readers. I myself tried to learn a few Norman songs on a clunky old acoustic I once had – one of my huge embarrassments is trying to play “Why Don’t You Look Into Jesus” at an Easter Seal Society camp where I worked – and I’ve been moved and inspired by some of his beauties. I’ve also railed plenty against some of the contradictions in his work. (He wrote more overtly about social justice than any similar CCM artist but yet sang wrong-headed rapture songs such as “I Wished We All Were Ready.” It has been featured recently in hit TV show The Leftovers and it still makes me cringe for its Biblical error and it’s anti-cultural legacy.) Since we here at the shop used to have one of the largest and certainly most interesting selections of Christian pop music on the East Coast, we’ve had lots of conversations about the strengths and weaknesses of many an artist, and often conversations circle back to Larry Norman. Before his death we carried all his old and rare stuff in our CD selection here at the shop so often talked with his dad, who ran his business (I learned from the book that Joe was not at all supportive for years) and even talked to Larry once on the phone. This book is personal for me, and I bet it is in many ways for many of you.

In case you wonder, I’m not making this up about how important he was and how much his artful life signified just because I’m a fan. Frankly, I have not been that much of a true fan, and although we happily sold (and continue to sell) his albums in our store, I was more taken with what he stood for and his impact than his actual records, some of which I thought were over-rated. But still, he was something.

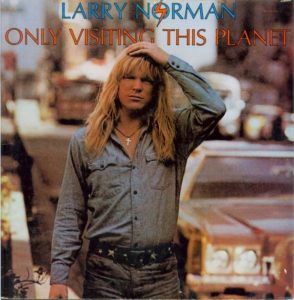

And he was, indeed, important, as Thornbury helps us appreciate. Billboard called Norman “the most important songwriter since Paul Simon.” The Huffington Post published an article dubbing him “The Most Amazing Artist You’ve Never Heard Of.” The Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry has honored his album Only Visiting This Planet as a “cultural, artistic, and/or historical treasure.”

And he was, indeed, important, as Thornbury helps us appreciate. Billboard called Norman “the most important songwriter since Paul Simon.” The Huffington Post published an article dubbing him “The Most Amazing Artist You’ve Never Heard Of.” The Library of Congress’ National Recording Registry has honored his album Only Visiting This Planet as a “cultural, artistic, and/or historical treasure.”

When he died, NPR feted him. Thornbury cites The London Times and notes the good reviews in Rolling Stone, and quotes The New York Times about him. Spin magazine did a back page tribute when he died, Thornbury tells us, again making the case that this colorful maverick ended up being a major influence in the culture of our times. Even Dylan liked him, and there’s a tender story to prove it.

Although it isn’t in the (too short) photo section of the book, I own a picture of Larry and Bono; when Bono went to Nashville to recruit CCM stars to his anti-poverty ONE campaign, his first question was “Will Larry Norman be there?” This is not insignificant.

I could explain more about this well-researched book; it covers his earliest days (his early  band People! played at the first big Be-In in Haight Asbury with Janis Joplin and the Dead and the beat poet Alan Ginsberg) and nicely notes some of the stars he hung out with and perhaps influenced – some say that The Who’s Tommy was somewhat inspired by Norman’s own work in developing rock operas, even as he crossed paths with the guy who played Jesus in Jesus Christ Superstar. He chatted with Neil Young and Stephen Stills in their Buffalo Springfield days; years later he played on the White House lawn for Jimmy Carter.

band People! played at the first big Be-In in Haight Asbury with Janis Joplin and the Dead and the beat poet Alan Ginsberg) and nicely notes some of the stars he hung out with and perhaps influenced – some say that The Who’s Tommy was somewhat inspired by Norman’s own work in developing rock operas, even as he crossed paths with the guy who played Jesus in Jesus Christ Superstar. He chatted with Neil Young and Stephen Stills in their Buffalo Springfield days; years later he played on the White House lawn for Jimmy Carter.

There is plenty about the rise and mediocrity of much of the CCM industry. There’s a bit about the business side of things; how could there not be? And some unpleasant stuff about his relationships, his failures.

And there is plenty about his controversy – with good lines like “Larry Norman entered the 1980s like a fugitive on the run from the Christian image police.”

More importantly, as a Jesus person who helped shaped the lingo and theology of the Jesus movement who despised the hypocrisy of the church and distrusted propaganda – especially religious propaganda – his influence was beyond the rock stars he shared the gospel with  and the fans that did or didn’t like him. I think much of the tone and texture of casual, non-fundamentalist, but still fiery evangelical outreach among youth in the 70s helped shape the nature of evangelicalism today. Of course some of his songs were in the influential Young Life songbooks that so many used at church camps and youth ministry events and the rise of para-church ministries (even like the CCO) took shape with long-hair and bell bottoms and Good News Bibles and Bible studies while sitting in circles on the lawn like hippies. That there is a sizable non-fundamentalist, culturally-savvy, socially relevant, and yet deeply orthodox Christian movement among baby boomers and their offspring comes in some ways from this legacy of the Jesus Movement days.

and the fans that did or didn’t like him. I think much of the tone and texture of casual, non-fundamentalist, but still fiery evangelical outreach among youth in the 70s helped shape the nature of evangelicalism today. Of course some of his songs were in the influential Young Life songbooks that so many used at church camps and youth ministry events and the rise of para-church ministries (even like the CCO) took shape with long-hair and bell bottoms and Good News Bibles and Bible studies while sitting in circles on the lawn like hippies. That there is a sizable non-fundamentalist, culturally-savvy, socially relevant, and yet deeply orthodox Christian movement among baby boomers and their offspring comes in some ways from this legacy of the Jesus Movement days.

There are academic books about all this, and I think they are on to something: whether you liked Norman’s music or not, whether you’ve even heard of Larry Norman or not, the size and zest and non-fundamentalist tone of the local community non-denominational church comes, in many ways, from those who grew up listening to bands like The Second Chapter of Acts and Larry Norman and Randy Stonehill and Daniel Amos and soft-rock Maranatha Praise music. That Bob Dylan added harmonica to a Keith Green album and artists as diverse as Eric Clapton (who was reading Francis Schaeffer) or Barry (“Eve of Destruction”) McGuire or Noel Paul Stookey or Alice Cooper or Earth Wind and Fire’s Philip Bailey were reading theology and talking about Jesus was no small thing. That a generation amidst the sexual and drug experimentation of the 70s was also connecting to evangelical faith in fresh ways with their own vocabulary and soundtrack helped shaped the social landscape of our culture today.

Here are some endorsements that might help illustrate how others are seeing the importance of this book:

“A mind-blowing portrait of evangelical Christianity’s one, and only, rock n’ roll wild child, a high-wire act of daring, revelation and empathy, as original as Larry Norman himself.”

–Charles Marsh, Professor of Religion and Society, University of Virginia, and author of Strange Glory: A Life of Dietrich Bonhoeffer

“If there truly was a great crossroads where the devil traded souls for music, then Larry Norman must have made his own visit. If it’s true that no musical genre can thrive if it does not own its roots, then this book is required reading for artists who have waded into the faith-based genre without tracing its origins back to where it first sprang from the earth.”

–Dan Haseltine, songwriter and producer, Jars of Clay and The Hawk in Paris

“In an American Idol world where trading on the name of Christ and unholy alliances with professional God-talkers can win you the White House, Gregory Alan Thornbury places before us a beautifully complicated Larry Norman, that enigmatic, trickster figure at the heart of the Jesus Movement. By doing so, he invites us to consider again the prophetic genius, the untamable poetic justice of Jesus of Nazareth, to whom Norman remained committed in spite of the dizzyingly false witness and geopolitical catastrophe conducted, even now, in his name. Hear Norman again, and have your senses restored.”

–David Dark, author of Life’s Too Short to Pretend You’re Not Religious

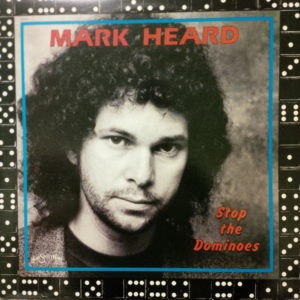

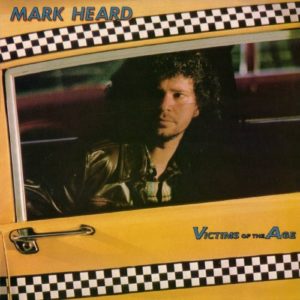

Besides the big legacy of helping to create, for better or worse, the multi-million dollar gospel music industry and subsequent subculture that gave us CCM, and the impact of that on a rising generation, the particular part of the CCM world Larry Norman specifically helped nurture was significant, too, giving us artists like Randy Stonehill (fans know about the on-again, off-again friendship of these two) and, significantly, Mark Heard, considered by some to be one of the great songsmiths of our time. I am glad that there is a bit about Mark Heard in Why Should the Devil including some lines from Larry spoken after Mark’s heart attack while performing at the Cornerstone Festival in August of 1992.

Mark had moved out of the CCM sub-culture for the most part, playing with folks like Buddy Miller and Bruce Cockburn, but for those of us who followed his work from the start, he will always be connected to Larry Norman.

SALE PRICE AND A FREE CD

And so, for a limited time – while supplies last – we will give you a free Mark Heard CD with a purchase of Why Should the Devil Have All The Good Music: Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock by Gregory Alan Thornbury. The book is 20% off and you get a free CD.

After Sunday March 25th the book will remain on sale, but the CD offer will be over.

It’s a long story but we have copies of two important, rowdy Mark Heard albums from the early 1980s, Stop the Dominoes and Victims of the Age. Tell us which one you want, absolutely free. You can listen to it while reading Why Should the Devil Have All the God Music? Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock by Gregory Alan Thornbury.

It’s a long story but we have copies of two important, rowdy Mark Heard albums from the early 1980s, Stop the Dominoes and Victims of the Age. Tell us which one you want, absolutely free. You can listen to it while reading Why Should the Devil Have All the God Music? Larry Norman and the Perils of Christian Rock by Gregory Alan Thornbury.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% Off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313

read@heartsandmindsbooks.com

717-246-3333