All of these books are on sale and can be ordered through our secure website. Just click on the order link at the end of this column. We will be sure to confirm everthing with a personal reply.

After a hard look at hard stuff during Holy Week, we are lead through the hell of Holy Saturday and, abruptly, into the joy and hope of Easter. I think the apostle Paul and countless apologists are right in saying everything hinges on the truth of the empty tomb. We must believe deeply in the resurrection of Jesus and, then, to use Wendell Berry’s famous poetic line, in the call to “practice resurrection.”

But what does it look like to be a practicing resurrectionary? And how do we bring light and goodness, victory and life, gospel grace and Kingdom power to the still broken world in which we live?

What does it mean to live well in a complicated Monday after a joyous Sunday?

A.J. Swoboda, who has written well in A Glorious Dark about the three days of Christ’s death, what is sometimes called The Triduum, gives us a hint in his major 2018 book, Subversive Sabbath: The Surprising Power of Rest in a Nonstop World; there he reminds us that keeping Sabbath, habits of rest and celebration epitomized in holidays like Easter, ends up subverting the dysfunctional ways of the world. Can holidays, and Christian practices connected to the resurrection really be subversive? Does faithful resurrectionary living present an alternative to the reigning status quo?

Our church (and maybe yours) gladly proclaimed the joy of new life in Christ, celebrating Jesus’ victory over the grave, the forgiveness of sin, but also teased out some of the implications of this newness that breaks in to human history. We confessed our sins, admitted our fears, came to grips with the foibles and failures of life East of Eden. And we were called to be transformed, through faith, by grace, to become people of the Kingdom, missional agents of God’s love in the world. I’m not sure our preacher used the word, but it was deeply subversive, if we realize what it means to “practice resurrection.” We proclaim “all things new,” after all.

Which necessarily leads us back into what is sometimes called “the real world.” To that popular verse in 1 Chronicles 12:32 about “sons of Issachar” who “understood the times and knew what God’s people should do.” After Easter, can we become sons and daughters of Issachar?

That is just what our books are designed to help you with.

Which, like it or not, necessarily leads back to big stories such as the release of the Mueller Report*, our President’s tweets, our local economies, our foreign affairs, the brokenness in which we are implicated, the “groaning of creation” itself (Romans 8: 19-22), and all the rest that might be considered current affairs.

*yes, you can pre-order it from us.

We are sent into the world and we simply cannot be “above the fray” of our contested politics.

I think it was Jim Wallis who I first heard say that Christian faith is “personal, but never private.” Like Abraham Kuyper said, Christ claims “every square inch” of the entire creation.

The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend our God-Blessed, God-Forsake Land David Dark (Westminster John Knox) $17.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $13.60

The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend our God-Blessed, God-Forsake Land David Dark (Westminster John Knox) $17.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $13.60

One of the most stimulating, thoughtful, remarkably-written, and provocative books I’ve read about the state of our times and the state of our union in these times is The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend our God-Blessed, God-Forsake Land written by my friend David Dark.

David is a lover of words, a lover of truth, a lover of what some call common grace – gladly thanking God for the signs of life that pop up in even a secularized culture, offered up even by those who seem not to be religious. (Ahh, there’s an interesting idea: is anybody really not religious? Don’t we all live by and for something? That’s the theme of Dark’s fabulous book called Life’s Too Short To Pretend You’re Not Religious [IVP; $18.00.] What a fascinating book!)

Discerning the signs of life or signals of transcendence in common grace gifts of popular culture is the theme of his only slightly dated first book Everyday Apocalypse: The Sacred Revealed in Radiohead, the Simpsons, and Other Pop Culture Icons (Brazos; $20.00.) He has for many years been helping us understand how to understand the culture, how to see the good and the bad, the sacred and the profane. (Or, should I say, the sacred in the profane. And vice versa.)

In a way, this new one about America is a continuation of that project, finding how deeply wise and transformative insights show up in the best of our American dream, from our politics to our classic landscapes, our shaping documents to our best literature and song. I joked to somebody in the shop that he should have called this Everyday American Apocalypse.

The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend our God-Blessed, God-Forsake Land is actually a considerable re-working and expanded edition of his 2005 book, The Gospel According to America: A Meditation on a Christ-haunted, God-blessed Idea. It is, for those who are familiar with that stimulating, much-discussed book, different enough that it demanded a new title; it is not just a “revised” edition. There’s so much new content in The Possibility of America that it earned a new title; not only is there considerable re-working and new content, the overall tone is a bit different. Understandably.

The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend our God-Blessed, God-Forsake Land is actually a considerable re-working and expanded edition of his 2005 book, The Gospel According to America: A Meditation on a Christ-haunted, God-blessed Idea. It is, for those who are familiar with that stimulating, much-discussed book, different enough that it demanded a new title; it is not just a “revised” edition. There’s so much new content in The Possibility of America that it earned a new title; not only is there considerable re-working and new content, the overall tone is a bit different. Understandably.

It seems to me that the very title indicates a change in the panic level of professor Dark, mirroring the anxiety many of us feel in these contested, Trumpian times. It was a bit easier (not that much, really, for those paying attention, but a bit) to see “the gospel” within America a decade ago. As the subtitle of that first book put it, we were in a “Christ-haunted” land. Now, with a vain sex offender known for his rude impetuousness and shameless dishonesty in our highest office, supported loudly by religious leaders who take pictures of themselves with him with photos of Playboy on the nearby wall, who say firmly, as Jerry Falwell, Jr. did, that he does not take his political cues from Jesus, who have actually affirmed inhumane treatment of immigrant families — tearing children from their parents – we are in, shall we say, a different position then we were before. These are awful times for the US of A, and it seems that anyone in touch with the Bible and the current political ethos simply has to wish things were otherwise.

Enter David Dark, who once was a bit less outraged and a bit less consumed by the dark antics of our leaders, and who has deepened his long standing passion for Biblical justice and relating prophetic truth to current realities.

Enter David Dark, who once was a bit less outraged and a bit less consumed by the dark antics of our leaders, and who has deepened his long standing passion for Biblical justice and relating prophetic truth to current realities.

Relating faith to popular culture and current events, by the way, is not new to him. In a weighty introduction called “Notes on the New Seriousness” he talks nicely about his father, a father for whom “the Bible was always in the back of his mind.” He tells us:

In his lifelong enthusiasm for candor, fair play, and the well-chosen word, freewheeling Bible study as a space in which everything could be talked about (war, celebrity, R-rated films, a living wage) was among my father’s favorite jams. Karl Barth’s dictum concerning life lived with a Bible in one hand and The New York Times in the other was an imperative he took up with glee.

He continues on about lessons learn from his father in this regard; I’m sure many of us envy being raised by a parent who, “as a conversation partner, treated words with an amused affection and reverence… “ Who offered a vibe of “conscience and candor.”

Dark describes his father, a lawyer, as one who understood how we fool ourselves, how we can use our virtue signaling for power, how we “can create or undo the impression of order and control through our use of language.” (Did his father read Derrida, or maybe just Amos and Jeremiah?) Dark talks about “disturbing the fixed scripts of the powerful.” And that “reverence and obsession are to one another near allied.” “For better or worse,” David says, “I am a child of his obsessions.”

No wonder he wrote a fascinating, stimulating book a few years ago called The Sacredness of Questioning Everything (Zondervan; $15.99.) (I might add, although it doesn’t add much, that I am honored to have a back-cover blurb on that one, sharing endorsement space with the late Eugene Peterson, who notes that Dark finds Jesus in surprising places and “he is also a reliable lie detector. And there isn’t a dull sentence in the book.”)

Dark is not only obsessed with lie detecting, with principles and words and “of who said what and how generalizing statements hide specific atrocities.” He is also obsessed – although it seems to come naturally to him – to say things in creative ways, putting side by side words that are not often combined, phrases that raise the eyebrow, that sometimes are jarring, sometimes amusing. (His sneaky little dropping of pop culture allusions, lines from rap songs or phrases from criticism or novels may go unnoticed by most – how many such “Easter eggs” did I miss, I wonder?) Which is just to say he’s a good, colorful, playful, if at times intense writer.

For instance, in that same serious introduction he describes his role as a teacher as the common good of attempted truthfulness. The paragraph-long explication of that sacred space is nearly worth the price of the book. “It could be the most insanely presumptuous task undertaken by any member of our species,” he writes. “I actually attempt to help people with their own thinking.”

I sit in classrooms with women and men in prisons and college campuses, and, together, we make assertions, put questions to one another, tell stories, read poems aloud, and wonder of our own words. They write sentences, I write sentences next to their sentences. And we get a conversation going somehow. We attempt truthfulness together. For some students, I sometimes have the feeling that this might be the first time someone’s calmly and respectfully urged them to think twice.

And, teacher that he is, obsessed with weighing in, he writes, furiously at times, hoping to help us think twice. Perhaps we need to see more clearly the shape we’re in, in this “God-forsaken” land. Or, perhaps, perhaps, we need to see the “possibility.” This book is his love letter to us all, even if it is more troubled and troubling than his first go at it in The Gospel According to America more than a decade ago.

The Possibility of America, as you can tell from the title, is still not without hope. Dark believes in the resurrection of Jesus, after all, and he loves our land. He loves our land passionately, concretely, especially as many Southerners do. Although his writing is at times dense and loaded with metaphor and allusion, he is not, finally, an abstract writer. He’s a deep and colorful thinker, but his writing is full of specificity, of place and details, of vim and vigor, as we used to say, salt and vinegar, maybe even fire and brimstone. And empathy and love and the occasional dose of self-deprecation and honest humility. He speaks his mind, tells stories, explores American writers and singers and films, and helps us see what kind of deep patriotic wells we might draw from in order to become more Christ-like and more earnest in our civic lives. In this, he seems to be nearly a postmodern, 21st century Will Campbell. Campbell, you might know, was a wordsmithy himself, published a theological journal, was a bit cantankerous, a Southern Baptist preacher who was a civil rights activist (the only white person at the founding of the SCLC) and yet friends with several Klansman. (“Jesus died for bigots, too,” he famously said.) It comes as no surprise that Dark cites Campbell’s classic memoir Brother to a Dragonfly.

Did I mention he draws on great America literature? Oh my, he starts with James Baldwin, and June Jordon, a hefty sign of where this might be going. He quotes public intellectuals, from Lincoln to Thoreau, from Octavia Butler to Wendell Berry. He loves American lit, and explains Faulkner (a lot of Faulkner), Cormac McCarthy, Melville (and more Melville), Whitman, on to contemporaries Thomas Pynchon, Kurt Vonnegut, Philip Dick, Ursula Le Guin, and Toni Morrison, among others. Who else these days recalls the televised conversation about poetry (and the detached judgment of analysis) between howling Allen Ginsburg and mumbling straight-man William F. Buckley?

If you know David (or read his Everyday Apocalypse) you know he’s going to cite Bob Dylan, and he does. Alongside Patti Smith, Chance the Rapper, and the lovely young alt-folkie Julien Baker.

David is a very creative writer and some may find him an acquired taste. This is a grand compliment – I regularly say it about two authors I adore, Calvin Seerveld and Daniel Berrigan (and, I suppose, James Joyce, although I haven’t acquired a taste for that kind of weirdness, yet.) It is interesting that David is a student of (saying a “fan of” would trivialize the matter) the poet, priest, and prophet, the late Daniel Berrigan. He thinks like him, it seems to me; he sounds like him. Maybe soon, David will end up in jail, like Father Berrigan — who knows? Civil disobedience, after all, is a very American custom and Biblical thing to do.

Berrigan (for those who weren’t taught it in school) was until his death last year a radical Catholic priest known for speaking truth to power by way of symbolic gestures of civil disobedience, disrupting state events, exposing the ludicrous idolatry of nuclear weapons (among other shameful atrocities, from torture to abortion to our neglect of the ill.) His poetry and Biblical commentary were held in great esteem among a rag-tag group of followers, many who joined him in non-violent civil disobedience and symbolic actions to dramatize the Bible’s call to repent from social injustice, such as throwing their blood on the pillars of the Pentagon, or chaining the doors shut of multi-national corporations profiteering from cluster bombs which knowingly target little children. The Berrigan Brothers (as he and his brother Philip were sometimes called) stood in an old tradition informed by the likes of Martin of Tours and Saint Francis and Tolstoy and Menno Simons and Franz Jägerstätter and Gandhi.

Importantly, they knew Martin Luther King and American resistors such as Howard Thurman and AJ Muste, were mentored by Thomas Merton, befriended by Dorothy Day. These are American icons that Dark is attuned to and to bring their witness into conversations with Faulkner and Stanley Kubric and Americana folk music and Star Trek and The Twilight Zone and rapper Kenrick Lamar is nearly genius; it’s a gumbo mix of high octane social theory, old school American literature, pop culture, and Biblical study yielding a prophetic public theology that could (please God!) lead us closer to Beloved Community.

I note that David is influenced by the Berrigans and writes in a verbose, eccentric style that is somewhat akin to poet Daniel. (Philip Berrigan was, by the way, stark and blunt, terse and no-nonsense. Of the two, who both wrote prodigiously, only Daniel would do a Bible commentary on the minor prophet called, with some sort of wink, Daniel.) It might be safer for David Dark of Nashville holding affiliations with an evangelical college to get at the foibles and possibilities of the deep American religious traditions by drawing on famously punchy and dark Flannery O’Connor (and he does, somewhat.) But it is brave, and even a bit unexpected, for him, in 2019, to release a book so deeply influenced in the witness of Dan Berrigan.

To wit: see also the great chapter by Mr. Dark on Father Berrigan in the wonderfully grand Eerdmans collection called Can I Get a Witness: Thirteen Peacemakers, Community Builders, and Agitators for Faith & Justice (Eerdmans) $26.99. OUR SALE PRICE = $21.59 I described this very sturdy and nicely bound hardback previously at BookNotes, exclaiming how profound this collection is, how needed. Edited by Charles Marsh, Shea Tuttle, & Daniel Rhodes, there are a baker’s dozen chapters by 13 deeply caring authors. Each good author tells about a certain American saint who lived out faith in robust and often-controversial ways, who took a stand, spoke out, paid up. The research for the book came out of a several year project overseen by Charles Marsh at the Project for Lived Theology housed at the University of Virginia.

To wit: see also the great chapter by Mr. Dark on Father Berrigan in the wonderfully grand Eerdmans collection called Can I Get a Witness: Thirteen Peacemakers, Community Builders, and Agitators for Faith & Justice (Eerdmans) $26.99. OUR SALE PRICE = $21.59 I described this very sturdy and nicely bound hardback previously at BookNotes, exclaiming how profound this collection is, how needed. Edited by Charles Marsh, Shea Tuttle, & Daniel Rhodes, there are a baker’s dozen chapters by 13 deeply caring authors. Each good author tells about a certain American saint who lived out faith in robust and often-controversial ways, who took a stand, spoke out, paid up. The research for the book came out of a several year project overseen by Charles Marsh at the Project for Lived Theology housed at the University of Virginia.

This Center has released other work exploring how theology and spirituality can be embodied and lived out and (more precisely) how lived experience (which includes social location) influences the doing of theology. They do oral histories, maintain various workgroups, and publish papers, reports, and a few scholarly books. Can I Get a Witness is their most important work yet, holding up major figures about which we simply ought to know more, all who can help nurture a “public conversation about civic responsibility and social progress.” There are chapters on famous thinkers and activists such as Cesar Chavez and Mahalia Jackson; they represent a variety of faith traditions such as Roman Catholic convert Dorothy Day, Native theologian, evangelical Richard Twiss, and ordained Baptist mystic and scholar Howard Thurman.

I have to admit I read David’s chapter on Daniel Berrigan first, even though there are other great chapters I couldn’t wait to explore. I knew he was re-working and re-issuing the expanded version of Gospel According to America, and thought it would be good to read David on Berrigan before taking in Possibility…

As I trust I’ve made clear, he has written about a variety of aspects of American culture and politics, if in a tone of “new seriousness.” The stern Berrigan-esque insight is prevalent but America is not just a nay-saying screed. He truly enjoys thinking about this stuff – one can tell, in part by the way his fertile mind jumps from this author to that, this episode of an old TV show to that, from a memory of being frustrated with a scene in Patch Adams to teaching us the importance of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury or riffing on the message of folk singer John Prine’s song “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get Your into Heaven Anymore,” or how one of his conversation partners (a student, perhaps?) put Wendell Berry in his pantheon of elders, “right up there with Tupac Shakur and Ursula K. Le Guin.”

As I trust I’ve made clear, he has written about a variety of aspects of American culture and politics, if in a tone of “new seriousness.” The stern Berrigan-esque insight is prevalent but America is not just a nay-saying screed. He truly enjoys thinking about this stuff – one can tell, in part by the way his fertile mind jumps from this author to that, this episode of an old TV show to that, from a memory of being frustrated with a scene in Patch Adams to teaching us the importance of Faulkner’s The Sound and the Fury or riffing on the message of folk singer John Prine’s song “Your Flag Decal Won’t Get Your into Heaven Anymore,” or how one of his conversation partners (a student, perhaps?) put Wendell Berry in his pantheon of elders, “right up there with Tupac Shakur and Ursula K. Le Guin.”

Or, in another vital paragraph, how he shows a quick genealogy of civil rights ideas that lead us to Beloved Community – “beginning with Moses telling the leaders of his world, ‘Let me people go,’ moving through the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom in August of 1963, and eventually arriving (but not stopping) at the day Beyonce’s Lemonade dropped…” He cites, then, a bunch of books of the Bible, leading to a reflection on the “Magna Carta of Christian liberty,” Paul’s letter to the Galatians. What a blast!

I love what Ohio poet and rock critic Hanif Aburraquib, author of They Can’t Kill Us Until They Kill Us says:

“It is an honor to watch his conflicts and curiosities bear themselves out on the page.”

You may need to think a bit more deeply about our current social situation, about our nation. You may not know where to start. I think this could help. Many others are raving about The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend Our God-Blessed, God-Forsaken Land, so consider these accolades:

“If I prayed, I would pray for all the David Darks—all the smart, funny, thoughtful, quirky, tough-minded, well-read, culturally-engaged Christians in America—to arise and speak up. Because I know that the crabbed, mean, unthinking forms of political Christianity that I see portrayed in the media are not the whole story.”

—Kurt Andersen, author of Fantasyland

“This revised edition of The Gospel according to America makes this prescient tome that much more salient. Dark regards America—real and imagined, secular and abidingly faithful, horrible and glorious—with a holistic gaze that holds these truths and contradictions together and examines the culture that comes from it in order to better understand just how we got here.”

—Jessica Hopper, author of The First Collection of Criticism by a Living Female Rock Critic

“This is a book built on the understanding that there is a civic imagination that imagines us into a better way of being human together. Taking Twitter, literature, poetry, music lyrics, film, television, cartoons and conversations as sacred texts, David Dark looks at the things that are held up by language: power, fear, and hatred. Dark’s work holds the hope that love is a muscle we can exercise in public—and he holds us to account for how we practice.”

—Pádraig Ó Tuama, Irish poet and theologian of reconciliation of the Corrymeela Community

FIVE OTHER BOOKS TO HELP US GLIMPSE THE POSSIBILITIES OF AMERICA

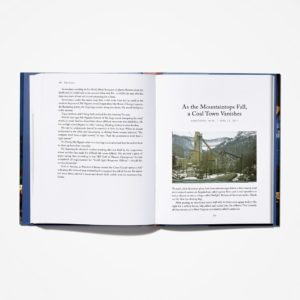

This Land: America, Lost and Found Dan Barry (Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers) $29.99 OUR SALE PRCE = $23.99 I came to respect Dan Barry as a extraordinary writer and dogged investigator and great storyteller when I read one of the most gripping books of creative nonfiction I’ve ever read, Boys in the Bunkhouse: Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland. (Enter it in quotations in our “search” box at the Hearts & Minds bookstore website and you can find my comments about it in December of 2016 or again when I awarded it Best Book award at the end of that year.) That award-winning expose moved me so that I explored his personal memoir, Pull Me Up, and then his great baseball book Bottom of the 33rd.

This Land: America, Lost and Found Dan Barry (Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers) $29.99 OUR SALE PRCE = $23.99 I came to respect Dan Barry as a extraordinary writer and dogged investigator and great storyteller when I read one of the most gripping books of creative nonfiction I’ve ever read, Boys in the Bunkhouse: Servitude and Salvation in the Heartland. (Enter it in quotations in our “search” box at the Hearts & Minds bookstore website and you can find my comments about it in December of 2016 or again when I awarded it Best Book award at the end of that year.) That award-winning expose moved me so that I explored his personal memoir, Pull Me Up, and then his great baseball book Bottom of the 33rd.

This beautiful and inspiring recent book is a collection of years worth of commissioned pieces that Barry was filing with The New York Times in his acclaimed “This Land” column. As he explains in the preface, they trusted him enough to send him wherever he wanted to go along with their finest photographers, to visit, to hang out, to snoop around, to catch the drift, and tell the stories of towns large and small, stories momentous and quiet. It is fabulously entertaining and, often, very deeply moving. We highly recommended it.

If David Dark is a literary and pop culture maven, if he’s an engaged theological thinker, if he has an agenda of learning from our God-haunted writers and critics and reformers so that we might be redemptive in stewarding the possibilities of a better nation, this book by journalist Dan Barry seems to have a more singular agenda: go places, meet people, tell their stories. Yet, this is not mere entertainment (a la Bill Bryson, say) but carries a goal of helping us to see and understand our fellow citizens, care about our country’s places, to be better neighbors and members of our commonwealth. It is truly top rate journalism written by a person of character and virtue, with the hopes of illuminating, too, the pains and the possibilities.

This handsome volume is illuminated with full color photographs from award-winning photojournalists, on thicker paper, making it nearly a keepsake volume. I agree with those who have said it is nearly a historic look at American life, from sea to shining sea. (There is even a chapter on Lancaster, PA.) This Land truly is a magnificent book and it would make a fabulous gift for anyone who cares about our place or enjoys reading short form creative nonfiction.

This handsome volume is illuminated with full color photographs from award-winning photojournalists, on thicker paper, making it nearly a keepsake volume. I agree with those who have said it is nearly a historic look at American life, from sea to shining sea. (There is even a chapter on Lancaster, PA.) This Land truly is a magnificent book and it would make a fabulous gift for anyone who cares about our place or enjoys reading short form creative nonfiction.

The compelling, enjoyable essays are grouped in categories; the dozen or so several-page pieces under each section have their own allusive and alluring titles, but room doesn’t not permit me to show them all. I’ll list the themed chapters, though, to give you a glimpse:

- Part One: Change – After the Ball is Over, After the Break of Dawn

- Part Two: Hope – Meet Me Tonight in Dreamland

- Part Three: Misdeeds – Here You Have Your Morning Papers, All About the Crimes

- Part Four: Intolerance – I’m Always Chasing Rainbows

- Part Five: Hard Times – Hard Times, Hard Times, Come Again No More

- Part Six: Nature – The Beautiful, the Beautiful River

- Part Seven: Grace – Ah! Sweet Mystery of Life

- Part Eight: The Ever-Present Past – Shine Little Glow Worm, Glimmer

- Epilogue: In the Middle of Nowhere, A Nation’s Center

Check out these wonderful endorsing blurbs. They are so intelligent and thoughtful and, we think, spot on.

Dan Barry is an American treasure, and This Land is a beautifully conceived, essential book on American lives and places. His understanding and love of the American experience — small towns, fractured lives, beauty, suffering, and the physical landscape — is unparalleled. I’m grateful to him, and for him, for chronicling our lives, honoring our history and recognizing our connection to each other. Rosanne Cash

Dan Barry gives dignity even to the darkest corners of the American experience. He is the closest thing we have to a contemporary Steinbeck. Colum McCann

This Land reminds us that the greatest strength of the American character is America’s characters: men and women who are resilient, gracious, eccentric, world-weary, bright-eyed, funny, complex, tragic, surly and yes, even, kind. Dan Barry proves once again that in his intelligent company, attention paid is its own reward. He assures us, too, that eloquence, wit, and compassion — all the virtues we need now — have not been purged from American discourse and are alive and well in these pages. Alice McDermott

What I Found in a Thousand Towns: A Traveling Musicians Guide to Rebuilding America’s Communities – One Coffee Shop, Dog Run, and Open-Mike Night at a Time Dar Williams (Basic Books) $27.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $21.60 We’ve carried the great Dar Williams’ music for years – yes, we still stock CDs – and when we heard she had a book coming out, I was excited. She is articulate, has a good eye for that curious detail, and is known as an environmental spokesperson. She cares about things that matter and has sung beautiful about life in our hurting world. (The New York Times review said this book was more a report from the Green party than the green room. Nice!)

What I Found in a Thousand Towns: A Traveling Musicians Guide to Rebuilding America’s Communities – One Coffee Shop, Dog Run, and Open-Mike Night at a Time Dar Williams (Basic Books) $27.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $21.60 We’ve carried the great Dar Williams’ music for years – yes, we still stock CDs – and when we heard she had a book coming out, I was excited. She is articulate, has a good eye for that curious detail, and is known as an environmental spokesperson. She cares about things that matter and has sung beautiful about life in our hurting world. (The New York Times review said this book was more a report from the Green party than the green room. Nice!)

And then, when we heard she was hanging around with new urbanists, talking about small towns, buying local, channeling Jane Jacobs (more than one review said that) we were even more eager to stock it. She has, after all, made her living – as she puts it – “not in stadiums but touring America’s small towns.”

Alas, she oddly – I’d say hypocritically – has only one link to sell her book at her website, and that’s to faceless, anti-small towners at greed-driven Amazon. Not even the customary “wherever fine books are sold” or “at your favorite bookseller.” No IndieBound link, nothing. Sigh.

Still, it’s a book some of our customers might enjoy and it reports on local communities in way that would compliment David Dark’s righteous possibility project:

What I Found in a Thousand Towns is a thoughtful and passionately explored journey of how American towns can revitalize and come to life through their art, food, history, mom-and-pop business, and community bridge building. Dar Williams gives us hope and vision for the possibilities of human connection. Emily Saliers, Indigo Girls

Dar Williams channels the soul and spirit of Jane Jacobs. With a songwriter’s eye for detail and an urbanist’s nose for what makes cities and towns work, she provides stunning portraits of America’s great small towns. What I Found in a Thousand Towns will open your eyes to the key things that makes communities succeed and thrive even when the deck is stacked against them. I love this book: You will too. Richard Florida, The New Urban Crisis

The Hard Way on Purpose: Essays and Dispatches from the Rust Belt David Giffels (Scribner Book Company) $16.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $12.80 Perhaps you recall that we named as one of my favorite books this past year the fabulously interesting, engaging memoir Furnishing Eternity: A Father, a Son, a Coffin, and a Measure of Life, a memoir about a guy in Akron, Ohio, who is a writer, community college teacher, and who is a bit of a wood-worker – he had written a previous memoir about fixing up his old house called All the Way Home: Building a Family in a Falling-Down House – who is making a casket with his engineer/ woodworking father. It is a book about small towns, about rock and roll, about father-son stuff, the lost arts of working with your hands, and a lot about the grief he experiences as he loses his best friend and beloved mother. It was a near prefect book for me – a memoir of a middle-aged guy with rock sensibilities, an irreverent streak, and a colorful, religious family. Building a coffin. What a great book!

The Hard Way on Purpose: Essays and Dispatches from the Rust Belt David Giffels (Scribner Book Company) $16.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $12.80 Perhaps you recall that we named as one of my favorite books this past year the fabulously interesting, engaging memoir Furnishing Eternity: A Father, a Son, a Coffin, and a Measure of Life, a memoir about a guy in Akron, Ohio, who is a writer, community college teacher, and who is a bit of a wood-worker – he had written a previous memoir about fixing up his old house called All the Way Home: Building a Family in a Falling-Down House – who is making a casket with his engineer/ woodworking father. It is a book about small towns, about rock and roll, about father-son stuff, the lost arts of working with your hands, and a lot about the grief he experiences as he loses his best friend and beloved mother. It was a near prefect book for me – a memoir of a middle-aged guy with rock sensibilities, an irreverent streak, and a colorful, religious family. Building a coffin. What a great book!

And so, I find he’s written a previous collection of pieces about rustbelt troubles and it strikes me to say that he is the real deal. These essays – which he describes as “wry and irreverent” — are about basketball (he grew up near LaBron James) and the auto industry (Akron was, after all, the rubber capitol of the world; so many people there worked for Firestone), rock and roll (there’s a blurb by a guy from The Black Keys, another Akron icon, not to mention Devo) and what it means to stay in a town most people leave.

These “dispatches” are about identity and place, about Ohio and the great Midwest. His publisher describes the book like this:

…David Giffels was born in Akron in the 1960s, as the golden age was ending, and has lived there ever since. Now he plumbs the touchstones and idiosyncrasies of a region where industry has fallen, bowling is a legitimate profession, extreme weather is the norm, thrift store culture dominates, and sports is heartbreak in a rarely told story of a unique American generation whose deep regional pride was born of economic failure and hardship. The Hard Way on Purpose is the story from the inside, written by someone who never left, about the life that goes on there and what it means. Intelligent, humorous, and warm, Giffels’s collection of linked essays is about coming of age in the Midwest, and the stubborn, optimistic, proud, and resourceful people who thrive there.

I mention this because it is a fun read, because we’ve got friends in that part of Ohio, because the writing is good, and because, somehow, his evoking of hope among underdogs seems to capture something, in a different tone and style, close to what David Dark is exploring. Can we draw upon our better angles? I doubt if Giffels would put it that way, but if you want a book to help you ponder the state of our union, this is a good, fun, way in.

The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life David Brooks (Random House) $28.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $22.40 We received a somewhat early edition of this and have been working through it bit by bit. I am a huge David Brooks fan, and appreciate his lucid and eloquent speaking and writing. I know those who are serious progressives distrust him since he is often pitched as the conservative voice on NPR or PBS. Conversely, some of my conservative friends roll their eyes when they think of David as a conservative, since they think he is way too liberal. In this regard he seems akin to another favorite pundit, The Washington Post’s Michael Gerson.

The Second Mountain: The Quest for a Moral Life David Brooks (Random House) $28.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $22.40 We received a somewhat early edition of this and have been working through it bit by bit. I am a huge David Brooks fan, and appreciate his lucid and eloquent speaking and writing. I know those who are serious progressives distrust him since he is often pitched as the conservative voice on NPR or PBS. Conversely, some of my conservative friends roll their eyes when they think of David as a conservative, since they think he is way too liberal. In this regard he seems akin to another favorite pundit, The Washington Post’s Michael Gerson.

Too liberal for the right, too conservative for the left?

Too intellectual for the populists, too much a popularizer for the elite scholars?

And, recently, as word of his embrace of Christianity has gotten out – one could see it coming in his previous The Road to Character – and as he has been befriended over the last decade by smart evangelicals, I wonder if he is now too religious for the secular mainstream and yet too open-minded for the religionists?

Maybe, even give that The Second Mountain is somewhat about his own religious pilgrimage, is he too Jewish for the Christians and too Christian to be a Jew?

Is he too widely read and none-dogmatic for the rigid evangelicals and yet too obviously religious for those who prefer their questing to be general, philosophical, spiritual, maybe, but not churchy?

Can people embrace a serious, public intellectual who says he is “a wandering Jew and a confused Christian”?

This remarkable just-released book deserves pages and pages of careful review, and I cannot do that yet. I mentioned it now, though, here, as it is very much related to the fundamental project of David Dark and his book on the possibilities of America – it starts with the exploration of the theme that we are happiest when we are living for something beyond ourselves. Which connects us to cares and causes societal and communal. In a way, this is a thought example of (or at least a prelude to) public theology.

As Mr. Brooks began to explore in his previous book, The Road to Character (Random House; $18.00) there is this huge question of how to live for something other than one’s self when we live in a self-centered culture? Where does that virtue come from, and how does one possibly sustain it? The first two chapters are called “Moral Ecologies” and “The Instagram Life.” What social pressures must we resist and how can we trust something other than our own shallow and finally unreliable selves?

One can immediately see the fingerprints of cultural critic and philosopher Charles Taylor and the evangelical Presbyterian pastor Timothy Keller. It may be surprising that Brooks – again, like David Dark – is fascinated with Dorothy Day. Day’s striking conversion from a secular worldview to historic, traditional Catholicism, and her subsequent piety linked to a passion for the poor (and her desire to overthrow what she called “this filthy, rotten system”) intrigues the conservative pundit. The Second Mountain is full of stories of people like Day whose lives were transformed by causes bigger than themselves and who found their way to religious faith as a key to their transforming vision.

I loved Brooks’ early books like the essential Bobos in Paradise and the fantastic one about suburban fascination with yards, On Paradise Drive. Of course we stock them both, not to mention The Social Animal and The Road to Character. But this new one is truly extraordinary, catapulting Brooks, I would think, into the major ranks of being a thoughtful, accessible, public intellectual rooted in the Christian tradition.

I loved Brooks’ early books like the essential Bobos in Paradise and the fantastic one about suburban fascination with yards, On Paradise Drive. Of course we stock them both, not to mention The Social Animal and The Road to Character. But this new one is truly extraordinary, catapulting Brooks, I would think, into the major ranks of being a thoughtful, accessible, public intellectual rooted in the Christian tradition.

That he has spoken at Q, has been on stage conversing (at Trinity Forum) with James K.A. Smith, has appeared with Miroslov Volf, and has sequestered himself with scholars at Wheaton College, is nothing short of remarkable for a public figure of his caliber and social situation.

As with his other marvelous books, he is astute in his critique of the American upper and middle classes, even has he seems to have considerable heart for a just social order that values the underclass and helps shape the common good. He is searching for that deeply moral life, emerging from his interest in character, and is candid about his own longing for meaning, purpose, joy, and what we too often too glibly call “a life well lived.” What intellectual and religious commitments are viable? He is trying to ask what causes human flourishing, what sustains it, and what kind of society can help provide the social architecture where it is more likely to occur?

Indeed, in a very important chapter after what seems to me to be the penultimate one about conversion (“A Most Unexpected Turn of Events”), there are several impressive chapters offering a study of community. Again, I cannot now quote the many good lines in this rich section, but he appreciates that we cannot do this stuff alone, that relationships matter.)

Brooks presents, as you might guess, good data and analysis and stories about those who make serious, life-enhancing moral commitments. That’s the “second mountain” – fashioning behaviors that bolster one’s commitments, supremely to family and vocation and community.

That fact Brooks’s own marriage ended (and he has since married a younger woman) has caused many to say he is hypocritical; it is, I suppose, an ironic elephant in the room (although he does mention it in the book.) You will have to decide if a book of astute moral persuasion about keeping family commitments and finding faith from a person from an admittedly broken family is acceptable. That he has been spoken of harshly and the book dismissed because of his frailty is, I think, disappointing. Regardless of what you think of the man and his personal situation, the book is one well worth reading.

Political Visions & Illusions: A Survey & Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies (2ND Edition) David Koyzis (foreword by Richard Mouw) (IVP Academic) $33.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $26.40 I have maintained since the first edition of this learned and exceptional book came out in 2003 that it is nothing short of essential for those wishing to think deeply and Christianly about faith and political life. In my first BookNotes review of it, I summoned Bible texts about the mind of Christ, about not being “taken captive” by worldy ideologies, about being “non-conformed” to the ways of this world through having a “renewed mind.” I hope you know those texts. The Bible is clear that we are to “take every thought captive” and as Al Wolters first taught me, the Greek word in Colossians 2:8 (similarly to 2 Corinthians 10:5) does not mean merely any bad thoughts – like take captive our propensity to lust or anger or envy, but theories. That is, we shouldn’t be taken captive by theories or ideas that are not themselves consistent with a Biblical view of reality.

Political Visions & Illusions: A Survey & Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies (2ND Edition) David Koyzis (foreword by Richard Mouw) (IVP Academic) $33.00 OUR SALE PRICE = $26.40 I have maintained since the first edition of this learned and exceptional book came out in 2003 that it is nothing short of essential for those wishing to think deeply and Christianly about faith and political life. In my first BookNotes review of it, I summoned Bible texts about the mind of Christ, about not being “taken captive” by worldy ideologies, about being “non-conformed” to the ways of this world through having a “renewed mind.” I hope you know those texts. The Bible is clear that we are to “take every thought captive” and as Al Wolters first taught me, the Greek word in Colossians 2:8 (similarly to 2 Corinthians 10:5) does not mean merely any bad thoughts – like take captive our propensity to lust or anger or envy, but theories. That is, we shouldn’t be taken captive by theories or ideas that are not themselves consistent with a Biblical view of reality.

Just a week or two ago I was having a pleasant conversation – a bit of a philosophical debate — with a man much more learned than myself; he has authored Christian books, in fact. He is esteemed in his field and I enjoyed our conversation very much. At one point, I said something about his particular field and areas of expertise and said I just didn’t think his view comported with what the Bible says. What does that have to do with it? he retorted.

I wish I had the time to remind him of 2 Corinthians 10:5 and Colossians 2:8 or Romans 12: 1-2 or other Biblical instructions about having a renewed mind, about not being accommodated to pagan notions, not even in our intellectual architecture. This is why we sell books, actually – to help cultivate a consensus among readers that we should, in fact, love God with all our minds, thinking in ways that are consistent with what God has revealed to be true. We all must be on guard against syncretism, an undiscerning mixing of Biblical views and ideas that have deep roots in non-Christan ways of seeing life. Both the left and the right have elements of this, and it won’t due to merely point fingers at the problems with the side we don’t like. We’ve all got work to do to be more faithful, wise, Biblical people in our views about our jobs, our politics, our economics, our public loyalties.

(This is not the time or place to write an essay about the dangers of wooden Biblicism. One doesn’t go to the Bible for scientific or economic or aesthetic or engineering theories or political policies as such. We study God’s world – reality! – but always in light of God’s Word. As the Bible says itself, it is a “light before our path” but not a direct manual for tax policy or law codes or art theories and whatnot.)

And so, we come to this new, considerably updated, seriously revised, important new edition of the best book that explores the implications of this call to not be taken captive by wrong-headed, unsound, theories and ideologies that are not consistent with God’s Word in the realm of political viewpoints.

Koyzis deserves a rigorous, rigorous review as he is an important scholar, a deep and widely-read thinker, and I don’t have the ability to do that, now (although I did discuss the first edition at length when it first came out; that old review can be found at our Booknotes archives.) But I will summarize it by saying that — to put it more simply than it deserves – critiques both the ideological left and right, liberals and conservatives, showing how their intellectual roots are deeply grounded in the soil of the French Revolution and, more broadly, the secularizing forces of the Enlightenment.

And in so doing, he shows us how, surprisingly, they have much more in common than we might first guess.

Dr. Koyzis, who has taught political theory at Redeemer University in Ancaster, Ontario (and writes at his Byzantine-Rite Calvinist blog and in journals such as First Things and Comment) is, besides being an astute political theorist and good teacher, a student of the big picture, the genealogy of ideas, discerning not just the zeitgeist like a son of Issachar, but the DNA of the ancestors of the zeitgeist. Dylan maybe said you “don’t need a weatherman to know which way the wind blows” but you sure need some schooling (and maybe Holy Spirit guidance) to know where it’s coming from. And why.

Those following King Jesus should be neither left nor right, I sometimes say, and, I will admit, it is a slogan verging on a cliché. Yet, for Dr. Koyzis, it is a very, very deep notion, rooted from  his own immersion in the profoundly Biblical political science of the likes of Groen van Prinsterer, the brilliant and feisty anti-French Revolutionary social theorist who framed much of the Christian political party that eventually came to be led by Prime Minister Abraham Kuyper in early 20th century Holland. That is, van Prinsterer (we have the new edition of his classic Unbelief and Revolution newly translated by Harry Van Dyke and re-issued by Lexham Press; $15.99) was the main intellectual leader behind Kuyper’s movement.

his own immersion in the profoundly Biblical political science of the likes of Groen van Prinsterer, the brilliant and feisty anti-French Revolutionary social theorist who framed much of the Christian political party that eventually came to be led by Prime Minister Abraham Kuyper in early 20th century Holland. That is, van Prinsterer (we have the new edition of his classic Unbelief and Revolution newly translated by Harry Van Dyke and re-issued by Lexham Press; $15.99) was the main intellectual leader behind Kuyper’s movement.

So. Political Visions & Illusions: A Survey & Christian Critique of Contemporary Ideologies is just what it says. Although erudite and astute, it is a broad and big survey of modern visions and ideologies and the principle (religious-like) presuppositions behind them. Dig a bit under the surface of liberals and progressives and conservatives and nationalists and populists, we find certain constellations of ideas which, when held up to the light of God’s Word, are simply found wanting. Indeed, they serve as such controlling ideas they become for their adherents, idols.

Koyyzis is more philosophically minded and profound than this, but let me use an example (not from his book, exactly) but merely as a simple illustration of our quandary and why this book is so important if people of serious faith are going to be more faithful in their citizenship. Many on the religious right believe, as a matter of deep, religious-like certainty, that Jefferson was right that “the government that governs best, governs least.” Big government is considered anathema. Now as a matter of pretty obvious common sense, in many ways this is a wise, prudent concern. (Although, to save me, I don’t know how a small government can regulate international airports or sustain interstate highways or monitor the safety of food and medicines.) But I get that big bureaucracies can be inefficient and stupid.

However, the question on the table is if Jefferson and the Republican adage is correct: does the Bible teach that? Does a Biblically-inspired sort of social theory yield such an idea? Does a Scripturally-directed Christian political theorist believe such a thing? I am not going to try to summarize Koyzis’s complex and nuanced critique of the left and the right and their respective views of the role and task of the State, Christianly conceived. But I will say this: I do not think one can make a case (short of emphasizing maybe a single verse) for a negative view of government, or any assumption that government should be small. (Or, for that matter, that taxes should be low, but, I digress.) If we are trying to honor God by developing a uniquely and distinctively Christian approach to our civic lives and our party involvements, we have to ask this kind of a question: are truisms and slogans and assumptions about government Biblically faithful? Without crude proof-texting, what do we think about basic notions of political  science, Koyzis is a help in this for those interested enough in working through a major book like this. Certainly anyone in public office or working for campaigns or interested in public affairs needs this sort of resource. It is less sprawling than Suicide of the West, the best seller by Jonah Goldberg (who makes no pretenses of trying to nurture a Christian perspective), but if one has interest in this sort of thing, Political Dreams and Illusions is your book.

science, Koyzis is a help in this for those interested enough in working through a major book like this. Certainly anyone in public office or working for campaigns or interested in public affairs needs this sort of resource. It is less sprawling than Suicide of the West, the best seller by Jonah Goldberg (who makes no pretenses of trying to nurture a Christian perspective), but if one has interest in this sort of thing, Political Dreams and Illusions is your book.

Listen to James Skillen, one of my favorite mentors in this area. He wrote, among other things, a major book on how different faith leaders down through church history understood the task, role, and limits of the state, The Good of Government. Until his retirement, Jim ran the non-partisan Center for Public Justice. Skillen writes:

This second edition of David’s great book is a gem. The brighter light he now shines on his assessment of modern ideologies comes from an in-depth assessment of the story each tells and the idolatry exhibited in each one. This also pushes Christians to examine the extent to which we may be compromising our dedication to God by bowing (even unconsciously) to other gods for political guidance. In this day of heightening nationalism, racism, terrorism, and sheer ignorance, the message of this book could not be more urgent or important. Read and discuss it carefully even if it takes weeks to do so. The multiple forces at work in our homelands and around the world will not be thwarted or redirected by one election or one major event. Christian love of God and neighbor demands responsible civic service and that requires the kind of understanding provided by Political Visions and Illusions.

Here is another of many endorsing blurbs from many sharp thinkers, public theologians, citizen activists, church leaders, and others from across North America. Mary Stewart Van Leeuwen is professor emerita of psychology and philosophy at Eastern University. She has long been engaged in public affairs, and she brings a thoughtful social science approach to her (evangelical feminist) citizenship advocacy. She writes,

David Koyzis introduces readers to the range of political theories that have emerged and competed for dominance since classical times. He carefully and respectfully separates wheat from chaff in each of them in terms of a Christian worldview, and in a style that is clear, irenic, and persuasive. The second edition helpfully updates the first in terms of major political events of the past two decades. In an increasingly polarized world, this kind of book is essential reading for concerned citizens of all political and religious leanings.

BookNotes

SPECIAL

DISCOUNT

20% OFF

ANY BOOK MENTIONED

+++

order here

this takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown PA 17313

read@heartsandmindsbooks.com

717-246-3333