At the intense N.T. Wright lectures earlier this week there were so many brilliant lines, so many echoes of inter-textual Biblical connections, and so many fresh insights into the bigger Biblical narrative unfolding and pointing towards Christ’s redemptive project of launching a new exodus into a new creation. He cited his important book How Christ Became King (HarperOne; $24.99) and we particularly showed off his latest book, The Paul Debate: Critical Questions for Understanding the Apostle (Baylor University Press; $34.95.) Those that know Tom Wright know that his work is appreciated by

At the intense N.T. Wright lectures earlier this week there were so many brilliant lines, so many echoes of inter-textual Biblical connections, and so many fresh insights into the bigger Biblical narrative unfolding and pointing towards Christ’s redemptive project of launching a new exodus into a new creation. He cited his important book How Christ Became King (HarperOne; $24.99) and we particularly showed off his latest book, The Paul Debate: Critical Questions for Understanding the Apostle (Baylor University Press; $34.95.) Those that know Tom Wright know that his work is appreciated by  diverse corners of the church – liberal mainline Protestant denominational folks sat next to Roman Catholics who were chatting with nondenominational evangelicals and conservative, confessional Reformed folk. The diversity of races, ethnic backgrounds, theological viewpoints and faith traditions was heartening to say the least.

diverse corners of the church – liberal mainline Protestant denominational folks sat next to Roman Catholics who were chatting with nondenominational evangelicals and conservative, confessional Reformed folk. The diversity of races, ethnic backgrounds, theological viewpoints and faith traditions was heartening to say the least.

And then, perhaps not even recalling how fraught with racial tension his host city of Baltimore is these days, he reminded us that one of the grand themes of Paul’s explication of the work of the cross is that those “far away become near” and that the centrality of the new community forged in Christ between first century Jews and Gentiles (underscored, by the way, in Wright’s studies of Romans) might help us even teach children of the church about racial reconciliation and how to navigate in faith the complexities of racial injustice. Of course we should proclaim that we should just love everyone, but the Bible – including the teachings around topics of Christ’s death, the atonement, and such – offers thick resources, sturdy ideas and fruitful directions for moving deeper into the questions of how to be agents of reconciliation within our pluralistic and multi-ethnic (and often unjust) society.

Baltimore is the hometown, by the way, of writer Ta-Nehisi Coates who has just won the prestigious National Book Award for his extraordinary, exceptionally passionate book Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau; $24.00.) The title itself is a phrase from Richard Wright, which should hint that Coates is an intellectual rooted in the broad, classic canon of African American literature. He grew up in the 1980s and ’90s inner city Baltimore, raised by parents who were militantly Afro-centric; his father was a former leader in the Black Panthers, became a librarian (specializing in rare writings by blacks, intellectual stuff written centuries ago and nearly lost to modern readers) at Howard University. His father started a small and very eccentric publishing house – we ordered from them years ago! – In Baltimore, and Ta-Nehisi grew up reading, reading, reading, everything from Richard Wright and James Baldwin and Malcolm to authors with exotic sounding names who wrote books like Black Egypt and Her Negro Pharaohs.

Baltimore is the hometown, by the way, of writer Ta-Nehisi Coates who has just won the prestigious National Book Award for his extraordinary, exceptionally passionate book Between the World and Me (Spiegel & Grau; $24.00.) The title itself is a phrase from Richard Wright, which should hint that Coates is an intellectual rooted in the broad, classic canon of African American literature. He grew up in the 1980s and ’90s inner city Baltimore, raised by parents who were militantly Afro-centric; his father was a former leader in the Black Panthers, became a librarian (specializing in rare writings by blacks, intellectual stuff written centuries ago and nearly lost to modern readers) at Howard University. His father started a small and very eccentric publishing house – we ordered from them years ago! – In Baltimore, and Ta-Nehisi grew up reading, reading, reading, everything from Richard Wright and James Baldwin and Malcolm to authors with exotic sounding names who wrote books like Black Egypt and Her Negro Pharaohs.

Coates tells of his growing up (“coming up” as he puts it) in Baltimore – the awful gangs and robberies, the drugs, the rise of hip hop, the violent and seemingly pointless urban schools, the rough and racist cops, and more – in a thrilling 2008 coming of age memoir called The Beautiful Struggle. I read this first to prepare myself for the New York Times best seller Between the World and Me. I knew Between the World… was going to be hard-hitting, painful, perhaps (it is written as an extended letter to his own 15-year-old son, advice and ruminations offered in an age of Trayvon and Ferguson) and having read his own coming-of-age story before tackling Between the World was good.

Coates tells of his growing up (“coming up” as he puts it) in Baltimore – the awful gangs and robberies, the drugs, the rise of hip hop, the violent and seemingly pointless urban schools, the rough and racist cops, and more – in a thrilling 2008 coming of age memoir called The Beautiful Struggle. I read this first to prepare myself for the New York Times best seller Between the World and Me. I knew Between the World… was going to be hard-hitting, painful, perhaps (it is written as an extended letter to his own 15-year-old son, advice and ruminations offered in an age of Trayvon and Ferguson) and having read his own coming-of-age story before tackling Between the World was good.

I simply could not put down The Beautiful Struggle, and I highly recommend it for those who are interested in memoir, in allusive, creative writing (he has been compared to James Joyce) and certainly for anyone interested in the stories and experiences of fellow Americans who grew up in almost exclusively black neighborhoods and schools. I’ve read a bit of this kind of literature and I must say I was still utterly drawn in, my own heart pounding in fear of gangs and guns, angry at dumb schools and cops, moved by the sub-plot about his parents, anxious about his teenage confusion – would he go to Howard, which his father called The Mecca and at which he worked in order for his children to be able to afford to attend? His timid efforts at dating, his discovery of African drumming, his feelings as his parents moved from his ‘hood — all of this rang so very true to me and I was sad for the story to end.

I have to admit, though, I kept an urban slang dictionary app open on my phone as I read because I simply didn’t know many of phrases or even the pop culture references (gansta rappers, video game characters, basketball stars.) The prose is high-octane, spectacular, moving from heartbreak to hilarity, from anger to rage, from sweetness to immense, profound sadness. It’s a wild ride, both the setting and the prose, and it was an incredible one to take.

There is a reason it was so esteemed and the raves were so substantial – you should see the fantastic endorsements by the likes of James McBride, Eric Dyson, Natalie Y. Moore, Michael Chabon, and Walter Mosley, and was widely reviewed in journalistic outlets from Essence to Entertainment Weekly to Kirkus Review.

The year’s award-winning Between the World and Me is equally passionate, in some ways more so, and includes many anecdotes from his earlier life as he passes on his wisdom, such as it is, about living in a racially unjust world, to his teen-aged son. Mr. Coates has honed his writing craft and his style a little less flamboyant (he now is a staff writer for The Atlantic and lives in Manhattan) and some would say the new book is more mature and deeper than his earlier memoir. Both touched me deeply, and I appreciated both. The new one is certainly more polemical as he explains to his son what it means to inhabit a black body in these days. He is in teaching mode, here, not just meandering through his past for the joy of it all, and he brings some of the fire of his father to bear on what his son must know.

And, of course, what it means and what he must know is often awful, with a constant realization of the gross ugliness of chattel slavery – the truth that the great, great grandmothers of those with black bodies were raped with impunity, the great, great, grandfathers sold and beaten and lynched. This is, like it or not, one of the inevitable realities of our culture; even our most beloved founding fathers were in league with great evil on this matter, and Coates reminds his son, and his readers, of why this matters yet today. It is powerful stuff, and vital.

(Jim Wallis of Sojourners has a book coming out early in the new year about race and racism which many have for years encouraged him to write, named America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America (Brazos Press; $21.99) which you can pre-order from us for 20% off. There will be a foreword by Bryan Stevenson, which itself I’m sure will be good. I don’t know if Jim will dwell on this as Coates does, but it is gruesome truth that such stuff happened in our land, not that long ago.)

(Jim Wallis of Sojourners has a book coming out early in the new year about race and racism which many have for years encouraged him to write, named America’s Original Sin: Racism, White Privilege, and the Bridge to a New America (Brazos Press; $21.99) which you can pre-order from us for 20% off. There will be a foreword by Bryan Stevenson, which itself I’m sure will be good. I don’t know if Jim will dwell on this as Coates does, but it is gruesome truth that such stuff happened in our land, not that long ago.)

I cannot now do an extended review of Between the World and Me which deserves consideration and critique, I think, but I will say just two things: firstly, Mr. Coates’s materialistic atheism – this stuff and this life is all there is – seems to have been merely inherited from the nearly Maoist worldview of his father, a rare father who loved him (few of his friends had father’s present in their lives) and sternly abused him, and who was devoutly anti-Christian. One would think that such a thoughtful person, in a polemical letter to his own son, would have invited him – yea, challenged him! – to think for himself, even on this matter of what is true about the most basic things. We get little self-doubt about that, and no encouragement to think the options through.

It seemed to me that Mr. Coates’s philosophical views are asserted but not always argued, and for an esteemed thought-leader and rising public intellectual to be so unforthcoming about the illogic of his Ivy League disinterest in religion (not to mention his glib dismissal of King and his religious nonviolence) was frustrating to me. I can appreciate a hard-won, intellectually substantive journey towards disbelief, or even a visceral antagonism to the repressive and toxic implications of conventional religion. But to fail to grapple with foundational questions about first things, in such an otherwise astute and eloquent and thoughtful work inviting his son to be principled, hopeful, humane and fully human, was disappointing. Perhaps Coates’s son will rebel a bit, as Ta-Nehisis did against his own father’s blind spots, and reconsider the philosophical assumptions and (seemingly) unexamined secularism which significantly shapes much of the discourse in Between the World and Me.

Secondly, although this book offers a radical – some would say extreme – view of race relations, there are moments here that are self-revelatory about Coates’s own foibles and fears. (His telling of his own fear of visiting Paris, and his love of the City of Lights once he went was just beautiful.) His description of falling in love with the classmate who became his wife is lovely.

Secondly, although this book offers a radical – some would say extreme – view of race relations, there are moments here that are self-revelatory about Coates’s own foibles and fears. (His telling of his own fear of visiting Paris, and his love of the City of Lights once he went was just beautiful.) His description of falling in love with the classmate who became his wife is lovely.

Many white readers, I can only suppose, will be shocked by some of the angers expressed here and a few might be shocked by the recounting of gross racial profiling and police abuse, even in Prince George’s County, outside of DC, where Coates was working as a reporter after leaving The Mecca. But no reader can be left unmoved — certainly not by one of the centerpieces of the book, the murder by police of a kind and gentle Christian college friend — and no father will close it failing to think about what he might say to his own son, of any race or any age, about the weight of history upon us. Yes, it is an outspoken critique of racism, mass incarceration, and the hardships faced by people of color and other minorities in our culture. But it is also a story, more than a cautionary tale, some hint of a ritual rite of passage for the day mentoring his son, a meditation on parenting, and at times a very poignant, if complicated, one.

An incident of his endangering his young son by seriously escalating a volatile argument with a white woman in a crowded mall was told frankly, examining the political and the personal, so to speak, with Coates saying what he regretted and what he did not about the scene. In many ways, he is his father’s son, righteously outraged, remembering much and refusing to allow us to forget what most blacks know in their bones. Black lives matter, indeed. But he lives a more affluent kind of life then his parents did, his own neighborhood and workplace are more diverse, and his own kind and playful spirit shines through. Yes, this is a hard book to read, but it will be seen by many, as Toni Morrison notes, as “beautifully redemptive.” She continues, “its examination of the hazards and hopes of black male life is as profound as it is revelatory.”

Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God Kelly Brown Douglas (Orbis) $24.00 I mentioned Baltimore. This author is herself a scholar near there (she teaches religion at Goucher College) and as a black woman (and Episcopal priest) has thought long about racial injustice. More to the point, as a mom of a black son she was profoundly shook by the Trayvon Martin case. Out of moral, prophetic outrage and person angst as an understandably worried mother, she set herself to study the history of the “Stand Your Ground” common law that was used as a defense for situations such as George Zimmerman’s shooting of Trayvon Martin. As Baltimore burned last year, Orbis Books, known for its liberation theology and social-justice minded resources (they published James Cone’s must-read The Cross and the Lynching Tree), rushed this book to press even as the author was speaking out and offering leadership to the faith-based racial justice movement.

Stand Your Ground: Black Bodies and the Justice of God Kelly Brown Douglas (Orbis) $24.00 I mentioned Baltimore. This author is herself a scholar near there (she teaches religion at Goucher College) and as a black woman (and Episcopal priest) has thought long about racial injustice. More to the point, as a mom of a black son she was profoundly shook by the Trayvon Martin case. Out of moral, prophetic outrage and person angst as an understandably worried mother, she set herself to study the history of the “Stand Your Ground” common law that was used as a defense for situations such as George Zimmerman’s shooting of Trayvon Martin. As Baltimore burned last year, Orbis Books, known for its liberation theology and social-justice minded resources (they published James Cone’s must-read The Cross and the Lynching Tree), rushed this book to press even as the author was speaking out and offering leadership to the faith-based racial justice movement.

I wish I had time to review this more substantially, but will at least explain this much: this book is an uncompromising study – very academic at times, laden with cultural studies lingo betraying her privileged place as a liberal religious studies professor – of the history of racial injustice in America, by studying the ways in which property and violence were construed by the formative thinkers that shaped the founding fathers. (That would be the often slave-holding, violent founding fathers, let us not forget!)

You will be surprised that a book about the justice campaigns developing after Trayvon and Michael Brown, Ferguson and Baltimore, begins with Roman legal thinker Tacitus talking about the Germanic peoples of the Black Forests. The racial feature of these pale skinned, red-haired people were described in ancient Rome, and the trajectory towards racial purity and eugenics and vile racism begins. Anglo-Saxon views of property and power developed – think John Locke, etcetera – undergirding certain assumptions about law and justice, and soon enough, well, you know. There is a connection between the old German woods, English philosophy of law, and slavery. It is, as the Declaration puts it, “self-evident.” What these white men saw as natural law — yes, she also explains Aquinas, and how the Reformers and Puritans later used such medieval notions theologically and politically — became codified in laws and common law, in civic culture and politics. The evil slave sales and mass rapes and lynchings and Jim Crow laws and mass incarceration culture are not accidents of history, but are shaped and authorized by political ideals and philosophical assumptions.

Stand Your Ground is a passionate, provocative, tireless expose of all this, from American exceptionalism to Manifest Destiny to the large and looming question of where God is found in all of this. Do black lives matter? Can the black church tradition offer particular insights for us all to move forward in our stand-your-ground culture with justice and honesty? It is not particularly nuanced or even fair, but it is a cry of the heart, a voice to hear. There are some historical connections here that I have not considered, at least not lately, and I am glad for this heavy, serious work.

A thought: one can disagree with some of this, with much of it, even, and still find it a valuable read. Her evaluations of how black bodies – given the Anglo-Saxon myths and narrative of (white) American exceptionalism – are always seen as guilty seems to me to be overstated, and I am distressed saying this, thinking she would merely say this proves her point. Is Douglas right that the question of whether black victims of police brutality are at all responsible, even in part, for the unjust crimes waged against them, is nearly irrelevant – that we always blame the victim, even in their graves? And if so, what are the implications of this for the common good? (Does she really mean to move from “blacks are always guilty” to “blacks are not ever guilty”?) What does it mean in a racially-charged culture to insist on fair trails for all? Does it matter at all that in some of the recent horrific shootings the victims did, in fact, use violence before they were shot? I do not mean to suggest in any way that this justifies police shootings; to imply, however, as Dr. Douglas does, that to mention this is inappropriate strikes me as unhelpful.

Further, I found some of her judgments lacking in charity; in one instance a white child, the child of family friends, said something obviously racist, and she opined that while the family surely did not teach their child these prejudicial attitudes “they clearly did nothing to prevent them.” What an odd thing to say – it is certainly not clear, since we have no way of knowing what these parents did or didn’t do to teach their child proper attitudes and facts about race relations. And what parent doesn’t know that kids blurt out embarrassing things in direct opposition to the values the parents tried valiantly to impart? I was just astonished that an editor would let such an unfair statement go unchecked – suggesting this was a clear matter, and the fault of the white parents – and sad that a person of faith harbored such thoughts about a woman she said was a friend.

Still, this was one important book, heavy and serious, documenting relentlessly the intellectual and cultural convictions that have shaped the mess we’re in. It is strong in intellectual history, but it also does close evaluations of contemporary media coverage (and not just the far-right talk shows, but respected guys like Matt Lauer and his interviews with the parents of Trayvon Martin, which Douglas shows as terribly unfair.) As H.H. Kortright Davis of Howard University School of Divinity says, “No one reading this well-researched and eloquent scholarly testimony will ever be the same again.” Let us hope this is so.

Ferguson & Faith: Sparking Leadership & Awakening Community Leah Gunning Francis (Chalice Press) $19.99 We all know how the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, reignited a movement there, and elsewhere, for racial justice, police reform, and urban renewal. In places like Ferguson young activists and older clergy marched side-by-side, forging a new alliance, a new civil rights movement. Last year in Missouri, many St. Louis area clergy stepped up to support the emerging young leaders, and Leah Gunning Francis (of Eden Theological Seminary in St. Louis) documented it all. She is a board member of the Religious Education Association and has provided pastoral leadership for several congregations, but her she is found interviewing folks on the street, literally. Some of these stories you may have heard, but I suspect most you have not. How interesting and good it is to read story after story of real pastors and Christian leaders and what they did in the protests and on-going campaigns for justice in that place. This really is a behind the scenes story!

Ferguson & Faith: Sparking Leadership & Awakening Community Leah Gunning Francis (Chalice Press) $19.99 We all know how the shooting death of Michael Brown in Ferguson, Missouri, reignited a movement there, and elsewhere, for racial justice, police reform, and urban renewal. In places like Ferguson young activists and older clergy marched side-by-side, forging a new alliance, a new civil rights movement. Last year in Missouri, many St. Louis area clergy stepped up to support the emerging young leaders, and Leah Gunning Francis (of Eden Theological Seminary in St. Louis) documented it all. She is a board member of the Religious Education Association and has provided pastoral leadership for several congregations, but her she is found interviewing folks on the street, literally. Some of these stories you may have heard, but I suspect most you have not. How interesting and good it is to read story after story of real pastors and Christian leaders and what they did in the protests and on-going campaigns for justice in that place. This really is a behind the scenes story!

Yep, this thrilling book is really a collection of stories – testimonials and reports – of activists and church folk and religious leaders who worked long hours in the streets during the uprisings in Ferguson. It offers the anecdotes and perspectives of the people who were directly involved. As Shane Claiborne put it, “Leah Gunning Francis has penned a theological memoir of a movement.”

I think it is valuable for us all to realize how some people of faith, of some sorts of churches, got out of the pews and into the streets, and what that was like for them. In a way, this is a guide for any of us, in any town, on nearly any issue, imagining how we might become more missional and engaged in local activism. Granted, this is a particularly dramatic situation, in a particularly urgent setting, with a specific crisis in view, but the bigger question of how to be involved in this kind of work is important.

(As is, by the way, the less dramatic, on-going work of “unleashing opportunity” for the poor and abused, pursued by engaged citizens and good neighbors, combining proposals for both volunteerism and political solutions. See the exceptionally helpful little book I’ve named before in this column, Unleashing Opportunity: Why Escaping Poverty Requires a Shared Vision of Justice by Michael Gerson, Stephanie Summers & Katie Thompson [Falls City Press; $11.99.])

(As is, by the way, the less dramatic, on-going work of “unleashing opportunity” for the poor and abused, pursued by engaged citizens and good neighbors, combining proposals for both volunteerism and political solutions. See the exceptionally helpful little book I’ve named before in this column, Unleashing Opportunity: Why Escaping Poverty Requires a Shared Vision of Justice by Michael Gerson, Stephanie Summers & Katie Thompson [Falls City Press; $11.99.])

And so, I invite you to read Ferguson & Faith, no matter if you live in a tense urban center or not, whether your congregation has been activist oriented or not. Listen to another religious educator – Evelyn Parker of Perkins School of Theology – who writes that “This book is required reading for clergypersons serving in congregations and social agencies regardless of their social location, as well as required reading for seminary students preparing for leadership in faith-based communities.” I’d expand that not just to clergy or seminarians, but anyone wanting to see how Christian faith can be lived out in this dramatic way. As Congressman Emanuel Cleaver, a U.S. Representative from Missouri writes, of those whose stories are told in this book: “They embodied the best of the human spirit that resonated with many around the globe and challenged this nation to live up to its ideal of liberty and justice for all.”

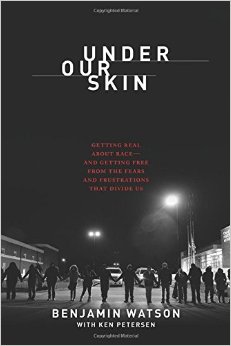

Under Our Skin: Getting Real About Race – And Getting Free From the Fears and Frustrations That Divide Us Benjamin Watson (Tyndale Momentum) $22.99 As you can tell from the other books listed, I think that there are serious, challenging, and hard-hitting voices that we need to hear. Coates rejects any semblance of a Christian worldview, but writes with heavy passion and award-winning eloquence. Rev. Brown is just as hard-hitting, or more so, as she shows the complicity of many theological systems and social philosophies that have authorized and motivated racial violence and white supremacy in the dominant culture. The Leah Gunning Francis book is less polemical, but tells the story of on-the-street and often in-your-face activists, insisting on reform and justice. These voices are not moderate, and I recommend them for just this reason. The cries are so urgent and anguished and those of us who are less aware of these issues really could benefit from immersing our selves with – being schooled, if you will – by those who see themselves as outspoken voices for change.

Under Our Skin: Getting Real About Race – And Getting Free From the Fears and Frustrations That Divide Us Benjamin Watson (Tyndale Momentum) $22.99 As you can tell from the other books listed, I think that there are serious, challenging, and hard-hitting voices that we need to hear. Coates rejects any semblance of a Christian worldview, but writes with heavy passion and award-winning eloquence. Rev. Brown is just as hard-hitting, or more so, as she shows the complicity of many theological systems and social philosophies that have authorized and motivated racial violence and white supremacy in the dominant culture. The Leah Gunning Francis book is less polemical, but tells the story of on-the-street and often in-your-face activists, insisting on reform and justice. These voices are not moderate, and I recommend them for just this reason. The cries are so urgent and anguished and those of us who are less aware of these issues really could benefit from immersing our selves with – being schooled, if you will – by those who see themselves as outspoken voices for change.

Benjamin Watson, an African American professional football player (tight end for the New Orleans Saints) is not exactly one of these hard-edged and prophetic voices. He speaks his mind as a black man who has seen discrimination up close and who knows what every black family knows, that it is not unlikely that his children will be followed by police, feared by strangers, treated poorly by the ignorant. He is not casual about this and he has spoken out.

But yet, as an evangelical Christian he is convinced that – as he put it in a Facebook post that went viral after the Michael Brown trial – we have a “sin problem not a skin problem.” In this, Watson spoke for many who wanted to admit that there are deep and tragic problems in our culture, including racism and police brutality, but that the deepest answers to these complex matters simply must deal with the sin of the human heart, and bring a gospel-centered response to the brokenness.

And that the ideological answers of the far left and the conservative right are both inadequate. We need nuance, balance, human-scale honesty and lots and lots of grace.

In a matter of days, Watson was an Internet sensation and was invited on national television. It was only a matter of time, I suppose, that he was invited to write a book.

I have some misgivings about how this works – crafting even a good Facebook post, even one that goes viral, does not necessarily mean the writer has a book in them. Too often publishers jump on the “next big star” who has thousands of twitter followers and a big platform. I hope you don’t think I am cynical for suggesting that a big platform does necessarily mean that one will speak with needed Christian wisdom and it does not authorize one to speak for, or even to, the Body of Christ.

In this case, I am happy to report, we have a thoughtful Christian leader who brings a great reputation and the ability to speak sensibly and thoughtfully into this very touchy and hard topic. I am very, very happy to recommend Under Our Skin: Getting Real About Race… for anyone wanting basic Christian insight offered plainly and clearly.

In this case, I am happy to report, we have a thoughtful Christian leader who brings a great reputation and the ability to speak sensibly and thoughtfully into this very touchy and hard topic. I am very, very happy to recommend Under Our Skin: Getting Real About Race… for anyone wanting basic Christian insight offered plainly and clearly.

Here’s a quick note: some (mostly white and mostly conservative) folks appreciated the football player’s passionate post because they thought it dismissed the radicals and their protesting. “It’s a heart problem, after all, spiritual, you know,” they thought. “Here’s a guy who gets that and knows that protesting doesn’t help. Jesus is the answer.” They might be surprised to see his further explications of his moving Facebook post that, while gentle in tone and Christ-focused throughout, are honest about naming social sin, describing the dangers and sad consequences of racism, and renouncing those who want to merely sweep it all under the rug. I think it will prove very valuable to educate and raise the consciousness of those evangelicals who might not realize just how pervasive racial tensions are, and how the gospel can addresses them, as such. That Watson is a known sports star doesn’t hurt either. He speaks for many a-political middle American’s, or so it seems to me.

Others, though, I think, (mostly considered liberal, I suppose, on this issue, at least) feared that Watson was doing an end run around the hard facts on the ground. Of course this is a skin problem – we are humans of different hues, actually, and some people think that those of lighter hues are better than others, and that those with darker skin are not to be trusted. It is sinful, of course, but to not name the sin what it is — racial injustice and white privilege — allows us to be so vague and general in our concern as to avoid denouncing the specific sin and thereby not owning up to it and the work that needs to be done. I admit I was concerned about this, given the title of his first Facebook post: he needs a dose of Race Matters by Cornel West, I thought. Is the brother Gnostic, pretending we don’t live in real skin, in a real world of real injustice? Again, these readers will be surprised to see that Mr. Watson doesn’t back away from talking about race, and doesn’t overlook the details of this racial crisis in our country. As Holly and Rodney Peete have written, “Under Our Skin is unflinchingly honest, strong and authentic. You won’t be able to put it down, and it will surprise, challenge, and inspire you in ways you never expected.”

To say he is “balanced” isn’t quite right, since that sounds so moderate, even-keeled, dispassionate, and this is not that. It is not ideological, it isn’t partisan, it holds out no easy answers. In this, it is profoundly Christian, I think, honoring the depth of the hard stuff, and yet still holding out hope, a hope based in the work of Christ and His redemptive purposes.

I am glad that so many folks are recommending this book. Tony Dungy says, “Benjamin Watson is one of the most intelligent and thoughtful men I have ever met, inside or outside of football… I know you will benefit from his insights into race and religion in the United States today.”

Barry Black Chaplain of the U.S. Senate, writes, “Packed with germane insights, this eye-opening book challenges current trends in American race relations, providing an important context for conversations about finding roads to racial unity.”

I hope knowing of these recent titles is somehow helpful. Perhaps you or your book club might tackle one of them, or you might commit yourself to reading on this topic, or leading conversations in your church or group. What do you think?

* * * *

Not long ago a customer asked what books I’d recommend for a reading plan exploring a Christian vision for concern about racial reconciliation. My reply to her wasn’t comprehensive, of course, but it did offer a nice selection of some of our favorites with which to start. Here is a slightly edited version of the reply I sent to her. I hope your know at least some of these. Happy reading!

Living in Color: Embracing God’s Passion for Ethnic Diversity by Randy Woodley (IVP) $18.00 This is one of our most-often recommended books in this field. Mr. Woodley is a deeply evangelical Native American, and so brings a healthy insight that our need for racial unity isn’t just about resolving “black vs. white” tensions, but must be increasingly multi-ethnic. Still, as a First Nation’s person of color, he is also deeply aware of the agonies of abuse, the legacy of slavery, Jim Crow and such. So he doesn’t gloss over the hard stuff. Still, it really is a lovely, solid book and very inspiring. I think this is really a great one to start with.

Many Colors: Cultural Intelligence for a Changing Church Soong-Chan Rah (Moody Press) $14.99 This is just a little more mature than some may whish, an excellent sociological study of the changing face of American culture and the Christian community. With the country’s demographics changing the conversations about race must be more than only about black and white tensions. Obviously are many Hispanic and Latino and Asian Americans of various sorts whose lives are different then many in the conventional white communities. Soong-Chan is a great and important voice lamenting the homogeneity in the white church and inviting us to move towards great diversity and sensitivity.

Divided by Faith: Evangelical Religion and the Problem of Race in America Michael Emerson & Christian Smith (Oxford University Press) $19.99 This is a very important little book, compiled by competent and respected social scientists, determining the exact details of racial segregation among evangelical Christians. The stories here are poignant, the data significant, the evaluation astute. Based on hundreds of interviews, Divided by Faith documents a lot of important findings, notably that there is a huge gap between what most white folks think about the prevalence and urgency of racism and what most African American’s perceive. In fact, at least according to their research, most white evangelicals see no systematic discrimination against blacks. The authors ponder how the individualism of most American evangelicals hinders their awareness of how things really are in our society. Fascinating!

More Than Equals: Racial Healing for the Sake of the Gospel Spencer Perkins & Chris Rice (IVP) $20.00 One of the very important books in this field, a best seller for years, nearly a contemporary classic in the field. It looks honestly at racism and why we simply must speak out — for the sake of the gospel! — but also about how hard it really is once we get beyond the nice rhetoric and good intentions. The late Spencer Perkins was the son of the legendary racial reconciliation leader John Perkins, raised in the inter-racial Voice of Calvary community in Mendenhall, Mississippi. (I hope you know his work and the amazing array of important books on this topic which he has written. It might be said that John Perkins was one of the most important evangelicals of the later part of the 20th century and helped put racial reconciliation and social justice “on the map” of 1970s evangelicalism after their complicity and silence during the historic civil rights struggles. His own autobiography is pretty widely respected, considered one of the important books of 20th century evangelicalism, Let Justice Roll Down. (And, sorry if I sound like I’m bragging a bit, be he offered a chapter in the book I edited, Serious Dreams: Bold Ideas for the Rest of Your Life. What an honor it was to have him involved!)

Welcoming Justice: God’s Movement Towards Beloved Community Charles Marsh & John M. Perkins (IVP) $16.00 This is one of John Perkin’s more recent books, a survey of the ways in which the gospel calls us all to struggle for social justice, economic unity, racial diversity and more. His co-author is a scholar of the civil rights movement (and a Bonhoeffer biographer, by the way) from the University of VA, and John, of course, is an evangelist and activist. Together they are a great combo, working together to tell the story and bring the message. This is, by the way, part of the excellent series of books on reconciliation produced by the Duke Center for Reconciliation. The first in that series is a must-read: Reconciling All Things: A Christian Vision for Justice, Peace and Healing by Emmanuel Katongole & Chris Rice (IVP; $16.00.)

Race Matters Cornell

West (Vintage) $14.95 This is one of the many by the outspoken black

intellectual, and is one of the most important books on this topic

written in recent decades. I highly recommend it, even though he, while

clearly a person of deep, articulate faith, grounded in both the

historic black church, the black liberation thinking of James Cone, and

the sophisticated social ethics of the likes of Reinhold Niebuhr, isn’t

quite an evangelical. Interestingly, it seems that he wrote this

important book somewhat in response to a book by Shelby Steele called The Content of Our Character. Steele

is a fascinating and eloquent conservative African American who thinks

much of the talk about racism is overdrawn and the best thing we can do

is stop talking about it. He thinks most of the ways we talk about race

is designed to help white liberals with their guilt which is the topic

of his more recent books. In The Content of Our Character Steele takes that one line from King’s famous “I Have a Dream Speech” and (without noting the rest of King’s work) says that not

commenting on skin color is what it is all about: that is, being color

blind. Basically he is saying that race doesn’t matter. Dr. West didn’t

cite Steele, but his passionate book later that year fired back “race

matters!” Both are important.

Forgive Us: Confessions of a Compromised Faith Mae Cannon, Lisa Sharon Harper, Troy Jackson, Soong-Chan Rah (Zondervan) $22.95 I actually have an endorsing blurb on this, raving about its importance. (One of my little claims to fame — ha!) I like the diversity of this team, all who are acquaintances — Mae is a deeply spiritual white woman, Lisa is a leader in social justice minded evangelicalism (and a black woman), Troy is a white pastor, now community activist, and Martin Luther King scholar, and Soong-Chan is of course Asian American. In this collection they lament the ways in which the church has been complicit in various injustices, against women and people of color and immigrants and the Earth itself. It invites us to confess our sins by at least knowing this history well and realizing the ways in which the reputation of Christ has been damaged by the ways in which the church has too often not been passionate about inclusion and care for those who have been oppressed. It is a powerful, important read, essential for moving forward, I’d say…

Just Mercy: A Story of Justice and Redemption Bryan Stevenson (Spiegel & Grau) $16.00 This is one of the most moving books I have ever read, and have described it often at our website. Maybe you know his passionate and articulate TED talk about injustices in prison sentencing, especially around the issue of children in prison. The whole movement against mass incarceration, what some called (inspired by Michelle Alexander’s book by this title) “The New Jim Crow” is about how many people of color, when arrested, get worse sentencing and worse treatment then their white counterparts who have the exact same crime. The institutional racism is undeniable, and Bryan’s work defending the poor and the needy, usually people of color, who are mistreated by the criminal justice system is simply a must read for anyone who wants to know about the reasons blacks often feel assaulted in our culture. Bryan spoke at our Jubilee conference years ago – he graduated from Eastern University, then went to Harvard Law School, and is a Christian hero of our times.

I’m probably giving you more than you need at this point, but I’m so grateful for your interest, that I’ll point you to this set of book reviews I did at our BookNotes blog a few years ago. We still stock these, so would be glad to have you order some! Thanks again for asking for our suggestions, and thanks for your support of our bookstore. We are grateful.

https://www.heartsandmindsbooks.com/booknotes/books_on_multicultural_reconci/

OR, more recently, this:

https://www.heartsandmindsbooks.com/booknotes/in_booknotes_a_few_days/

BookNotes

DISCOUNT

ANY ITEM MENTIONED

20% off

order here

takes you to the secure Hearts & Minds order form page

just tell us what you want

inquire here

if you have questions or need more information

just ask us what you want to know

Hearts & Minds 234 East Main Street Dallastown, PA 17313 717-246-3333