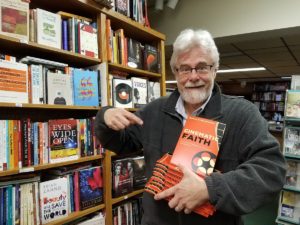

In this week’s BookNotes I will review a new book that we think is very good, a lot of fun, and even, I would say, important. It’s important for ordinary folks as well as for those who study this particular field professionally. Its retro cover matches the topic: Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective on Movies and Meaning by Calvin College film studies professor (and excitable film buff) William D. Romanowski (Baker Academic) $22.99. Our 20% OFF ON SALE discount makes it just $18.39.

In this week’s BookNotes I will review a new book that we think is very good, a lot of fun, and even, I would say, important. It’s important for ordinary folks as well as for those who study this particular field professionally. Its retro cover matches the topic: Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective on Movies and Meaning by Calvin College film studies professor (and excitable film buff) William D. Romanowski (Baker Academic) $22.99. Our 20% OFF ON SALE discount makes it just $18.39.

There are a plenty of things I want to tell you about this interesting new book but I’d like you to indulge me a bit with a bunch of other comments first.

You can just jump right to it by scrolling down to the review itself if you’d rather. You can even just skip to the bottom and easily click on the “order here” tab at end of this column to be taken to our secure order form page if you just want to order it now. We’re ready to send ‘em out.

But first, this.

WE’VE BEEN ON THE ROAD AT SEVERAL CHURCH-RELATED EVENTS

We’ve been on the road a lot this season and we want to thank those who hosted us at big gigs across the mid-Atlantic. Our on-line/mail order business friends say they enjoy hearing about our escapades here and there, so I want to ruminate just a bit on selling books at church events.

I have a particular observation that might sting just a little, but I’m surely not intending to diss our good friends in Lutheran, UCC, Episcopal and Presbyterian (USA) circles; we love doing this off site gigs. My observation will be a segue to telling you more about Dr. Romanowski’s great new book about the movies.

We are tired but yet exhilarated by our work at this recent string of clergy and church events. We loudly thank all those who helped us lug and unload or lug and reload our vans in recent weeks. We couldn’t do this work without the help of friends with strong backs. Thanks to friends old and new.

Over just the last few weeks we’ve gotten to set up big book displays for several great church events. We’ve put miles on the vans and lugged boards and shelves and supplies and boxes and boxes (and more boxes) of books to an Episcopalian retreat with The Rev. Fleming Rutledge (a hero of ours – you should read her many books! Her most significant work is The Crucifixion: Understanding the Death of Jesus Christ although, The Battle for Middle Earth, her

major work on Tolkien’s “divine design” is majestic) to a church education conference with PC(USA) Presbyterian congregational educators, to a UCC clergy convocation (with Sarah Griffith Lund leading as a vibrant speaker whose book Blessed Are the Crazy: Breaking the Silence about Mental Illness, Family and Church explores hard mental health issues in typical churches), to a small academic theology conference about Mercersburg Theology (where we launched a brand new and quite lovely introduction to that 19th century movement by Erskine professor William Evans called A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology in the “Cascade Companions series) to a large central Pennsylvania ELCA Synod Gathering where they re-

major work on Tolkien’s “divine design” is majestic) to a church education conference with PC(USA) Presbyterian congregational educators, to a UCC clergy convocation (with Sarah Griffith Lund leading as a vibrant speaker whose book Blessed Are the Crazy: Breaking the Silence about Mental Illness, Family and Church explores hard mental health issues in typical churches), to a small academic theology conference about Mercersburg Theology (where we launched a brand new and quite lovely introduction to that 19th century movement by Erskine professor William Evans called A Companion to the Mercersburg Theology in the “Cascade Companions series) to a large central Pennsylvania ELCA Synod Gathering where they re- elected their current very good Bishop.

elected their current very good Bishop.

We are glad to report that our biggest seller at that big gig was the most recent book by our friend Wes Granberg-Michaelson called Future Faith: Ten Challenges Reshaping Christianity in the 21st Cenutury (Fortress; $18.99.) Thanks to Bishop James Dunlap from teaching from it.

We often smile about and enjoy the theological diversity in these groups; around the spacious book displays we discuss the theological wisdom of popular authors like Richard Rohr or Diana Butler Bass or Tom Wright or Barbara Brown Taylor and debate the usefulness of words like evangelical or progressive, liturgical or Reformed. I often (unsuccessfully, I might add) try to sell them books like Evangelical, Sacramental, Pentecostal: Why the Church Should Be All Three by Gordon Smith (IVP; $18.00) or Rich Mouw’s wonderful Restless Faith: Holding Evangelical Beliefs in a World of Contested Labels (Brazos Press; $19.99.) I always takes books about ecumenicity and Christian unity such as Costly Love: The Way to True Unity for All the Followers of Jesus by John Armstrong (New City Press; $15.95.)

With these folks we celebrate their vibrant churches and share the anxiety about the numerical and financial decline of mainline congregations. We delight in the vision and energy of young, creative (and often quite theologically aware) clergy and mourn the loss of aging pastors that we’ve known for years who are no longer in ministry. We are glad when we hear about how the gospel is being proclaimed and people being served in and through congregations large and small, in cities and towns and rural areas. What a privilege!

We are told over and over that our books make a difference, that our presence matters at these denominational events. Historically, mom and pop Christian bookstores have been part often simplistic pietistic and fundamentalist traditions and have sometimes not been very serious-minded about theology; they have often eschewed working with mainline congregations. When large evangelical chains won’t even carry certain Bible translations or the work of certain publishers, there is good reason for animosity towards Christian booksellers among mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics. We have been graced by those in mainline circles who have welcomed us, knowing that we are a mom and pop, small town, Christian bookstore whose most core convictions remain orthodox. And we are grateful for

We are told over and over that our books make a difference, that our presence matters at these denominational events. Historically, mom and pop Christian bookstores have been part often simplistic pietistic and fundamentalist traditions and have sometimes not been very serious-minded about theology; they have often eschewed working with mainline congregations. When large evangelical chains won’t even carry certain Bible translations or the work of certain publishers, there is good reason for animosity towards Christian booksellers among mainline Protestants and Roman Catholics. We have been graced by those in mainline circles who have welcomed us, knowing that we are a mom and pop, small town, Christian bookstore whose most core convictions remain orthodox. And we are grateful for  those who have trusted us.

those who have trusted us.

We do have good resources for local congregations seeking congregational revitalization, for those doing strategic planning, missional discernment, for those starting spiritual formation groups, revisiting mission statements, searching for a pastor and the like. Whether you want to explore more creative worship planning or are doing appreciative inquiry, or are hoping to move your congregation towards social justice advocacy, we have books to suggest. We have oodles of books on congregational stewardship, on church conflict, on pastoral integrity,

on leadership development, youth ministry, and Christian education. Some rather evangelical books can be wisely used by mainline folks and we have tons of books from more liturgical, mainline traditions. We take books like The Art of Transformation: Three Things Churches Do That Change Everything by Paul Fromberg, one of the priests at St. Gregory of Nyssa (Church Publishing; $18.95) or Becoming a Just Church: Cultivating Communities of God’s Shalom by Adam Gustine (IVP; $17.00.) or the new one by the remarkable Peter Steinke, Uproar:Calm Leadership in Anxious Times (Rowman & Littlefield; $19.95) and dozens and dozens more.

on leadership development, youth ministry, and Christian education. Some rather evangelical books can be wisely used by mainline folks and we have tons of books from more liturgical, mainline traditions. We take books like The Art of Transformation: Three Things Churches Do That Change Everything by Paul Fromberg, one of the priests at St. Gregory of Nyssa (Church Publishing; $18.95) or Becoming a Just Church: Cultivating Communities of God’s Shalom by Adam Gustine (IVP; $17.00.) or the new one by the remarkable Peter Steinke, Uproar:Calm Leadership in Anxious Times (Rowman & Littlefield; $19.95) and dozens and dozens more.

Many folks at these mainline denominational events, clergy and congregants alike, it seems are not very aware of the often very thoughtful resources that are out there. From Eerdmans to IVP, from the defunct Alban Institute (whose books are still available!) to broad-minded evangelical presses like Zondervan and Baker, there are tons of resources for congregational health. I wish more church leaders – elders, vestry members, council members, deacons, vicars, and the like – reached out to us and sought out resources to help them with their vows of service to the local church. There’s literally something for everyone. We can help.

A CURIOUS THING WE OFTEN HEAR FROM FOLKS AT THESE EVENTS

But here is what we often notice – and this is the long-in-coming segue to my book review this week: people especially love the books that we bring that are a bit surprising, books that are not about the church, but about the arts or science, creation-care or nurturing a sense of vocation that allows people to serve God in the work-world. One doesn’t need to read  Abraham Kuyper who used that great phrase about Christ being Lord of “every square inch” of His creation to understand that God cares about more than our churches. (Although it wouldn’t hurt to get it from the proverbial horses mouth – the third Pro Rege: Living Under Christ’s Kingship volume in the massive Kuyper translation project was just released (Lexham Press; $49.99) offering remarkable insight about cultural engagement from the early 20th century Dutch theologian and statesman.)

Abraham Kuyper who used that great phrase about Christ being Lord of “every square inch” of His creation to understand that God cares about more than our churches. (Although it wouldn’t hurt to get it from the proverbial horses mouth – the third Pro Rege: Living Under Christ’s Kingship volume in the massive Kuyper translation project was just released (Lexham Press; $49.99) offering remarkable insight about cultural engagement from the early 20th century Dutch theologian and statesman.)

People seemed surprised so see that we feature books that remind us that God cares about Monday as much as Sunday. That all of us who follow Jesus are called to obey God by helping serve the common good. That this somehow means being in but not of the world, in civil society, the arts, education, recreation, politics, and more.

(Do please read last week’s BookNotes review of Jake Meador’s new book In Search of the Common Good: Christian Fidelity in a Fractured World and note the great chapters about how simple practices of going to church can help equip us to become better civic-minded public servants and good neighbors. As I explained, his study of culture is astute and his call to be active in the local church is so helpful, even though it’s a book about repairing society, healing the world, and seeking the common good.)

(Do please read last week’s BookNotes review of Jake Meador’s new book In Search of the Common Good: Christian Fidelity in a Fractured World and note the great chapters about how simple practices of going to church can help equip us to become better civic-minded public servants and good neighbors. As I explained, his study of culture is astute and his call to be active in the local church is so helpful, even though it’s a book about repairing society, healing the world, and seeking the common good.)

(And then back up and read my big review Romans Disarmed and Walsh & Keesmaat’s radical call to be a subversive community that stands with the hurting, even in an age of imperial injustice. There’s so much to be found in their amazing book Romans Disarmed: Resisting Empire/Demanding Justice and even my wordy review doesn’t tell it all. Both books show that a Biblically-grounded sort of socially engaged gospel depends upon a quality of congregational life that nurtures a lifestyle of stewardship, compassion, and activism.)

(And then back up and read my big review Romans Disarmed and Walsh & Keesmaat’s radical call to be a subversive community that stands with the hurting, even in an age of imperial injustice. There’s so much to be found in their amazing book Romans Disarmed: Resisting Empire/Demanding Justice and even my wordy review doesn’t tell it all. Both books show that a Biblically-grounded sort of socially engaged gospel depends upon a quality of congregational life that nurtures a lifestyle of stewardship, compassion, and activism.)

As much as mainline church seminary profs like to dabble in edgy and often eccentric theologies that are supposed to be empowering and relevant, most mainline churches are way behind the best evangelicals in fostering conversations around the intersection of faith and science, art, business, work, even racial reconciliation. Few mainline churches (judging from what we hear at these events, at least) are doing much in their churches about relating faith to stuff other than churchy or missionary things. When at mainline denominational events for church folk we display books about art or culture or work or science, there is almost always a bit of surprise. Folks are overjoyed to see Madeline L’Engle’s Walking on Water: Reflections on Faith and Art or The Language of God and Science by pioneering researcher of the human genome, Francis Collins or Josh Larsen’s excellent Movies Are Prayers: How Films Voice our Deepest Longings but you can tell that many have never seen books like that before. People do a double take when they see books about the doctrine of vocation, or books like Os Guinness’s The Call next to books about work and the marketplace. They seem to think that sensing God’s call only means being called to church life or religious things.(Curiously, in many more traditionally evangelical events, it is almost expected that we’ll have books on work and race and art and technology and civic life.) In our recent string of events everybody was delighted when they saw that we had, say, Wendell Berry’s agrarian books or David Brooks’ social criticism or Makoto Fujimura’s artful study of Endo’s novel Silence (in Mako’s wonderful Silence and Beauty: Hidden Faith Born of Suffering) or Sherry Turkle’s critique of digital culture or Andy Crouch’s wonderful Tech-Wise Family or Robert Capon’s “culinary reflection” Supper of the Lamb or books about sports and recreation. But mainline denominational folks tend not to buy them. They notice — books about faith and food, faith and popular music, books about hiking? But it seems surprising to them. And the pastors, usually, skip right over those things as if faithful reflection about real life doesn’t interest them much.

I don’t know if the surprise is that evangelical booksellers like us are savvy about life in the real world (do they think I’m a little hobbit sitting in a cave reading theology all day?) or that there even is such a thing as a Christian perspective on seemingly secular things like advertising or sports or neuroscience or work or film. This observation vexes me a bit.

BEING ECUMENICAL, YES

Almost everywhere we go we like to display books that honor our deep commitment to ecumenicity. As a matter of principle we like to offer both evangelical and progressive stuff; we always have Roman Catholic authors mixed in with Protestant books. We carry Chesterton and Nouwen and Alexander Schmemmann; Joan Chittister, John Stott and Walter Brueggemann; we feature Bible books by the late Rachel Held Evans and conservatively Reformed Bible teacher Nancy Guthrie. We have books on sexuality by Wes Hill and Matthew Vine and Austen Hartke side by side. Mainline folks rarely buy C.S. Lewis, but we take his stuff and put him near Rowan Williams and Marcus Borg. Maybe it was only to amuse myself, but in a recent display I put John Piper’s little Why I Love the Apostle Paul: 30 Reasons next to our stack of Romans Disarmed: Resisting Empire/Demanding Justice.

But being ecumenical is only one of our passions.

A BROAD VISION OF THE WIDE SCOPE OF REDEMPTION

As you can guess, we are passionate about this wholistic vision – learned mostly from the likes of Francis Schaeffer and Abraham Kuyper and in books like Creation Regained: Biblical Basis for a Reformational Worldview by Al Wolters and Heaven Is Not My Home: Living in the Now of God’s Creation by Paul Marshall and Engaging God’s World: A Christian Vision of Faith, Learning, and Living by Cornelius Plantinga – about how we can find God in the ordinary stuff of life and how we are called by God to be faithfully attentive about how to think and live in all spheres of life; no arena of culture or aspect of society or corner of your life is off limits to the saving power of Christ and the renewing power of the Spirit. It hardly needs saying – but yet, in religious circles, it does – life in God’s creation is multi-dimensional. We think and feel, work and play, vote and shop. Theorists of all sorts get at this when they talk about two hemispheres of the brain or when educators talk about multiple intelligences or even when we hear about personality types (like with the recent interest in the Enneagram. As multi-faceted people made in God’s image, we are more than bodies and souls. Which is why the church must proclaim a big gospel of all sides of life and why faith-based booksellers must carry resources for living in every sector of life and culture.

As you can guess, we are passionate about this wholistic vision – learned mostly from the likes of Francis Schaeffer and Abraham Kuyper and in books like Creation Regained: Biblical Basis for a Reformational Worldview by Al Wolters and Heaven Is Not My Home: Living in the Now of God’s Creation by Paul Marshall and Engaging God’s World: A Christian Vision of Faith, Learning, and Living by Cornelius Plantinga – about how we can find God in the ordinary stuff of life and how we are called by God to be faithfully attentive about how to think and live in all spheres of life; no arena of culture or aspect of society or corner of your life is off limits to the saving power of Christ and the renewing power of the Spirit. It hardly needs saying – but yet, in religious circles, it does – life in God’s creation is multi-dimensional. We think and feel, work and play, vote and shop. Theorists of all sorts get at this when they talk about two hemispheres of the brain or when educators talk about multiple intelligences or even when we hear about personality types (like with the recent interest in the Enneagram. As multi-faceted people made in God’s image, we are more than bodies and souls. Which is why the church must proclaim a big gospel of all sides of life and why faith-based booksellers must carry resources for living in every sector of life and culture.

We are not just “brains on a stick” to use Jamie Smith’s colorful phrase or disembodied souls, like some mystics imply. From sex to science, from law to leisure, God’s creation is the “theatre of God” (to quote John Calvin) so all human endeavor is irreducibly religious. That is, all of life is lived – like it or not – corem deo; before God. We are in God’s world, living before the gracious Holy One, 24/7. As one recent book title by an Anglican leader, Win Mott, puts it, The Earth Is the Lords: There Is No Secular. We may live in a cultural era which is called “the secular age” but that is about the ethos of our time. We can live as if there is no God and our our cultural landscape can be arranged without reference to Christ’s reign, but we our hearts are still committed to some story, something religion-like. What we really trust can be misguided and our religion can be an idolatrous one, making an idol of our sense of self or some other ideology, but worship we do.

From a Christian perspective, all of life is at once good and bad; blessed, cursed, damaged, and being redeemed and healed by the resurrection power of the Ascended King. We can serve that God of the Bible with all we’ve got or we can allow our hearts desires to move us in another direction with all we’ve got. It’s really pretty simple: as that old hymn puts it, “This Is Our Father’s World” and (as Richard Mouw unpacks in a book title taken from that same hymn) “He shines in all that’s fair.” God is pleased when we do what the Apostle says in 1 Corinthians 10:31: “Whether you eat or drink, do all to the glory of God.”

So folks walk into the book room at a conference or, more so, into our Dallastown bricks and mortar store, and see books on Van Gogh and cooking and nursing and engineering – books written often by wise authors calling for reform in the profession or industry — and if they look carefully they will realize that the authors may be people of deep Biblical faith, writing some of these books, integrating, if you will, their Sunday beliefs and their Monday world. From school  teaching to lawyering, from math to aesthetics, from farming to journalism, there are Christian authors offering up their workspaces as holy ground, as mission fields. There are people that get what my friend John Van Sloten says in his clever book title (and very excellent book) Every Job a Parable: What Walmart Greet, Nurses and Astronauts Tell us About God. Such folks may not be church leaders but they are trying to be salt and light, leaven in the loaf, blooming right where they are planted in the factory floor or work cubicle or sculpting studio or kindergarten classroom.

teaching to lawyering, from math to aesthetics, from farming to journalism, there are Christian authors offering up their workspaces as holy ground, as mission fields. There are people that get what my friend John Van Sloten says in his clever book title (and very excellent book) Every Job a Parable: What Walmart Greet, Nurses and Astronauts Tell us About God. Such folks may not be church leaders but they are trying to be salt and light, leaven in the loaf, blooming right where they are planted in the factory floor or work cubicle or sculpting studio or kindergarten classroom.

It is why we often recommend the great collection of Christian graduation speeches about taking up our  callings to serve God in professions and careers that I compiled, Serious Dreams: Bold Ideas for the Rest of Your Life (Square Halo Books; $13.99) and why I’m sad when people think that even young adults wouldn’t be interesting in such a thing. It is unfortunate, I think, of how few churches honor their college grads. Maybe if we all read Serious Dreams it might help.

callings to serve God in professions and careers that I compiled, Serious Dreams: Bold Ideas for the Rest of Your Life (Square Halo Books; $13.99) and why I’m sad when people think that even young adults wouldn’t be interesting in such a thing. It is unfortunate, I think, of how few churches honor their college grads. Maybe if we all read Serious Dreams it might help.

One would think one would be delighted to see books about real life in the real world that might make you say, and mean it, “Thank God It’s Monday!” But, as I say, people smile and seem surprised, and maybe a tad confused.

I GIVE THIS SPIEL BECAUSE OFTEN PEOPLE ARE SURPRISED

I give this little spiel often at our book display at conferences. It seems that I have to explain these kinds of books to most church folks at a church conference when they see – often with delight – that we’ve got books like Watching TV Religiously or Game Day for the Glory of God: A Guide for Athletes, Fans, & Wannabes or Craig Detweiler’s iGods: How Technology Shapes our Spiritual or Social Lives or Robert Benson’s spiritual meditation on his backyard called Digging In or that great Square Halo Book release edited by Gregory Thornbury on Doctor Who, Bigger on the Inside: Christianity and Doctor Who. If they look at the table of contents, we are sure to have a little conversation about something in Steve Turner’s book Popcultured: Thinking Christianly About Style, Media and Entertainment. Who knew there were Christian insights about fashion and video games and comedy?

I was dismayed that a book that is getting rave reviews in places like Christianity Today called Seculosity: How Career, Parenting, Technology, Food, Politics, and Romance Became Our New Religion and What to Do about It by Dave Zahl didn’t sell at our recent mainline gigs, even though Fleming Rutledge (an Episcopalian) had a great blurb on the back, and it is published by the ELCA-related Fortress Press. It is an interesting, playful, grace-filled, feisty study of our culture – the sort of things he does at his exceptional website and podcast Mockingbird.

I was dismayed that a book that is getting rave reviews in places like Christianity Today called Seculosity: How Career, Parenting, Technology, Food, Politics, and Romance Became Our New Religion and What to Do about It by Dave Zahl didn’t sell at our recent mainline gigs, even though Fleming Rutledge (an Episcopalian) had a great blurb on the back, and it is published by the ELCA-related Fortress Press. It is an interesting, playful, grace-filled, feisty study of our culture – the sort of things he does at his exceptional website and podcast Mockingbird.

Maybe people are surprised to see these kinds of books because their pastors don’t talk about all this; their adult ed forums during the education hour at church don’t tackle these sorts of things in principled ways. Or maybe it is because (at least the last time I formally investigated this, admittedly years ago) there simply weren’t many Christian bookstores that stocked faith-based books about helping us be whole-life disciples across the whole of life and culture. For a few years I’d call the new winner of the “Best Christian Bookstore” award and ask if they had books on, say, art, or if they had a political science department, or any books about urban planning. Or even books about racial reconciliation. Often the clerk was baffled. We’re a Christian bookstore one dear frontline staffer replied, as if that settled things. Of course God Almighty doesn’t care about art or science or public policy. And these are the best CBA stores!

EYES WIDE OPEN

One book we always take out with us to events is Eyes Wide Open: Looking for God in Popular Culture (Brazos Press; $24.00.) It is a personal favorite written by an old college pal, author of the brand new Cinematic Faith, William D. Romanowski. Decades ago in those critical years, under the influence of older mentors in the CCO, we talked about this “all of life redeemed” vision, learned the deeper meaning of worldviews and social imaginaries as we read Dutch philosophers and colorful Christian thinkers like Bible scholar, art historian, and aesthetician, Calvin Seerveld. Bill nearly memorized most of Cal’s seminal Rainbows for the Fallen World (Toronto Tuppence Press; $35.00) and to this day laughs about helping scholarly, artful Cal learn a bit about popular entertainments. Soon, Bill felt the call to do PhD work in the study of popular culture; these were the days when MTV was a new thing, when film was starting to use rock music in soundtracks (the topic, in fact, of his first co-authored book.) He prepared to make a contribution to the burgeoning field of pop culture studies by getting his PhD at Bowling Green (then the epicenter of much of this academic study, using a bit of critical theory and other new ways to discern what is really going on in popular entertainment and cultural proclivities and social practices. His Pop

One book we always take out with us to events is Eyes Wide Open: Looking for God in Popular Culture (Brazos Press; $24.00.) It is a personal favorite written by an old college pal, author of the brand new Cinematic Faith, William D. Romanowski. Decades ago in those critical years, under the influence of older mentors in the CCO, we talked about this “all of life redeemed” vision, learned the deeper meaning of worldviews and social imaginaries as we read Dutch philosophers and colorful Christian thinkers like Bible scholar, art historian, and aesthetician, Calvin Seerveld. Bill nearly memorized most of Cal’s seminal Rainbows for the Fallen World (Toronto Tuppence Press; $35.00) and to this day laughs about helping scholarly, artful Cal learn a bit about popular entertainments. Soon, Bill felt the call to do PhD work in the study of popular culture; these were the days when MTV was a new thing, when film was starting to use rock music in soundtracks (the topic, in fact, of his first co-authored book.) He prepared to make a contribution to the burgeoning field of pop culture studies by getting his PhD at Bowling Green (then the epicenter of much of this academic study, using a bit of critical theory and other new ways to discern what is really going on in popular entertainment and cultural proclivities and social practices. His Pop  Culture Wars: Religion & the Role of Entertainment in American Life (Wipf & Stock; $45.00) remains a major work – critiquing, by the way, the very way we assume that there is a difference between high art (that we should study and learn from) and low art, or pop culture (which, well, is just amusement, after all, or so many assume.) That the original cover had a picture of Rocky Balboa and William Shakespeare and Bruce Cockburn made a nice point. Bill was a lit major in college, was a performing artist himself, had worked in campus ministry with emerging adults (through the CCO) and soon became perhaps the leading voice in the early 1990s discussions about evangelical faith and popular culture. He was speaking widely and doing research and meeting important voices in the entertainment industry. (The picture above, by the way, is with the legendary Jack Valenti, the late President of the Motion Picture Association — you know, the institution that runs the Academy Awards and gives out the Oscars.

Culture Wars: Religion & the Role of Entertainment in American Life (Wipf & Stock; $45.00) remains a major work – critiquing, by the way, the very way we assume that there is a difference between high art (that we should study and learn from) and low art, or pop culture (which, well, is just amusement, after all, or so many assume.) That the original cover had a picture of Rocky Balboa and William Shakespeare and Bruce Cockburn made a nice point. Bill was a lit major in college, was a performing artist himself, had worked in campus ministry with emerging adults (through the CCO) and soon became perhaps the leading voice in the early 1990s discussions about evangelical faith and popular culture. He was speaking widely and doing research and meeting important voices in the entertainment industry. (The picture above, by the way, is with the legendary Jack Valenti, the late President of the Motion Picture Association — you know, the institution that runs the Academy Awards and gives out the Oscars.

As you may recall from our BookNotes review, in 2012 he released a major scholarly work, published by Oxford University Press entitled Reforming Hollywood: How American Protestants Fought for Freedom at the Movies. It remains a standard study in the history of film, and especially Protestant engagement, about which little has been written. Romanowski had remarkable access to important archives and did interview with older Hollywood producers, including some ground breaking research into the role religion or didn’t play in the formation of the now famous MPAA rating system.

As you may recall from our BookNotes review, in 2012 he released a major scholarly work, published by Oxford University Press entitled Reforming Hollywood: How American Protestants Fought for Freedom at the Movies. It remains a standard study in the history of film, and especially Protestant engagement, about which little has been written. Romanowski had remarkable access to important archives and did interview with older Hollywood producers, including some ground breaking research into the role religion or didn’t play in the formation of the now famous MPAA rating system.

LOOKING FOR GOD IN POPULAR CULTURE

Eyes Wide Open: Looking for God in Popular Culture (in an expanded second edition) was his first popular level book and it became a perennial best seller. It is still one of the very best books to offer a broad and thoughtful Christian worldview as a lens to help us be faithful and discerning in engaging modern entertainment. From video games to televised sports, from advertising to rock shows, Eyes Wide Open helps us understand how pop culture works, how it both reflects the dominant culture’s values and shapes them. And how it can – from varying viewpoints and perspectives – help us criticize and even be motivated to reform society. (Erin Brockovich, anyone? The Big Short? Dallas Buyers Club? Selma?)

Anyway, Eyes Wide Open is a fine and thoughtful book, only a bit dated, now, and still my favorite resource for thinking in foundational ways about the joys and challenges of watching movies and listening to music and such. If you don’t have it, you should. If you were with us at any of the aforementioned church conferences you probably saw it. Maybe you were intrigued. I know we didn’t sell any.

(By the way, another vital favorite, which we also take everywhere we go – with a more allusive writing style, and a bit more punchy evaluation of important popular culture works – is David Dark’s amazing Everyday Apocalypse: The Sacred Revealed in Radiohead, The Simpsons, and Other Pop Culture Icons (Brazos Press; $20.00.) Don’t you love the cool, old-school juke box on the cover design?

(By the way, another vital favorite, which we also take everywhere we go – with a more allusive writing style, and a bit more punchy evaluation of important popular culture works – is David Dark’s amazing Everyday Apocalypse: The Sacred Revealed in Radiohead, The Simpsons, and Other Pop Culture Icons (Brazos Press; $20.00.) Don’t you love the cool, old-school juke box on the cover design?

David is the one who wrote The Possibility of America: How the Gospel Can Mend our God-Blessed, God-Forsaken Land that I reviewed at length at BookNotes a month or so ago. Why are some folks surprised that a Christian bookstore stocks and promotes these kinds of books?

And can you help us fix this problem by promoting in your circles books about culture, the arts, society, science, work, citizenship, play, education, health care technology, food, farming and more?

Maybe, at least, you could invite them to subscribe to our free BookNotes so they learn about these kinds of books… we’d appreciate it and it would serve to advance the cause of thoughtful Christian literature.

ANNOUNCING: CINEMATIC FAITH A CHRISTIAN PERSPECTIVE ON MOVIES AND MEANING

Years in the making, we are very, very glad to get to announce a brand new book by professor Romanowski. As we’ve said, it’s called Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective on Movies and Meaning (Baker Academic; $22.99 – OUR SALE PRICE = $18.39) and I’m reading through it happily for the second time. For anyone who likes going to the movies or can’t wait for the next NetFlex DVD to show up (please don’t tell me you watch films on your little phone!) this big book will be an education and a joy. It isn’t preachy and it isn’t simplistic but it isn’t overly academic. If you love movies, you need this book.

Years in the making, we are very, very glad to get to announce a brand new book by professor Romanowski. As we’ve said, it’s called Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective on Movies and Meaning (Baker Academic; $22.99 – OUR SALE PRICE = $18.39) and I’m reading through it happily for the second time. For anyone who likes going to the movies or can’t wait for the next NetFlex DVD to show up (please don’t tell me you watch films on your little phone!) this big book will be an education and a joy. It isn’t preachy and it isn’t simplistic but it isn’t overly academic. If you love movies, you need this book.

READING DOESN’T HINDER OUR PLEASURE

Let me get this off my chest right away: reading books about various aspects of our Christian discipleship — work, play, voting, shopping, being a parent, being a choir member, considering schooling or health care or gardening, or vacationing, watching movies, whatever – isn’t going to dull our enjoyment of these good spaces where we live out our lives.

No! Unlike the beloved but confused chorus that says when we turn our eyes to Jesus “the things of earth will grow strangely dim,” the Bible says the opposite: Jesus is the Light of the world. In Him we are given light to see (the Bible is, after all, a light before our path!) So knowing God more deeply and deepening our faith and catching a vision of how it connects to various spheres of society and sides of life allows Christ to shine in all of life – we don’t want our marriages or work or our voting or our church life or our entertainment life to grow dim. We are to let our light shine! John 10:10 promises an abundant life, not a dim life.

READING ENHANCES OUR FAITHFUL ENJOYMENT

However, to really shine, to see God’s common grace in ordinary things, knowing something about those ordinary things is essential. Our enjoyment of making and eating good food is enhanced when we read a thoughtful cookbook! Our enjoyment of sports is better when we know some of the nuances of the game. We can even enjoy politics (Lord help us) when we know something about what we’re voting on and why we get passionate about it. Dare I say that some of us might enjoy sex a bit more if we read a book or two about Godly married life. Reading rock criticism or film studies or a book about the nature of digital culture and the like allows us do what the Bible says: attend to and listen to God’s will revealed in reality. (Psalm 19 says the heavens speak to us; Job says to “listen to the fish” and Isaiah 28 compliments a farmer for learning the science of soil and seed. This is basic to life: wisdom and joy come from knowing where we are and learning something about what we’re doing — whatever it may be. Systematic theology and inner spiritual formation and hearty worship cannot replace the need to pay attention to what Matthew Crawford calls “the world outside your head.” Biblical wisdom always is down-to-Earth, often quite literally. Reading and study is necessary and it can truly help us life in fidelity to God’s good ways. It’s as simple as that.

Books help us see and appreciate and develop the creation God has given us. To use the language of Andy Crouch’s essential text, we become Culture Makers who “recovery our creative calling” and can then, as Romanowski puts it, “find God in popular culture.” (By the way, we take Crouch’s Culture Making everywhere we go, too – it’s such a very, very helpful book to help us find meaning and purpose in our day to day lives.)

Books help us see and appreciate and develop the creation God has given us. To use the language of Andy Crouch’s essential text, we become Culture Makers who “recovery our creative calling” and can then, as Romanowski puts it, “find God in popular culture.” (By the way, we take Crouch’s Culture Making everywhere we go, too – it’s such a very, very helpful book to help us find meaning and purpose in our day to day lives.)

Who doesn’t want to understand what it means that we are made in God’s image and therefore called to be creative, involved in culture? Who doesn’t long for more God sightings in daily life? Who doesn’t want all of life to be worship – including, in this case, taking in goofball comedies, romance flicks, or action adventure films? Books like this will help you have more fun at the movies. And, trust me on this: Bill has very eclectic tastes and has a lot of fun at the movies.

(A fun little fact: Bill was led to Christian faith and discipled mostly by a guy who became not only a mentor but one of his life-long best friends. This guy, Dr. Terry Thomas of Geneva College, was himself raised working in a Pittsburgh-area movie theatre that his father managed. Nobody has more fun at the movies than Terry, who Bill mentions in his book. Terry’s love of film, including comedy, is infectious, and Bill learned well.)

MOVIE MUSINGS

One of the great delights of Cinematic Faith are a handful of (sometimes lengthy) “Movie Musing” sidebars where to illustrate his point in a given chapter, Romanowski explores some detail or theme in popular films.

From the “married life” sequence in Up to looking at “Dramatizing Drone Warfare in Eye in the Sky” to a brilliant analysis of history in the movie Lincoln to a fun interpretation of “time loop fiction” by way of a study of (what else?) Groundhog Day to one called “Boy Meets Girl in La La Land” these are all fascinating (even if you haven’t seen the film under consideration.)

Bill has spent considerable scholarly energy studying melodrama (and, for example, Titanic) and he loves Rocky (which, in a “Movie Musing” he calls “A Classical Hollywood Film.”) He offers musings on Blade Runner and The Imitation Game as metaphors, “art and ethics” in  Rear Window, and a great piece called “Narrative, Character and Perspective in The Blind Side” – you’ve got to read that if you enjoyed this movie as much as we have. Through all of these excursions, you can tell that his tastes are not overly high-brow. (Remember his central thesis of Pop Culture Wars that all film and pop artifacts are religiously/philosophically laden and artfully serious, and his central thesis of Eyes Wide Open

Rear Window, and a great piece called “Narrative, Character and Perspective in The Blind Side” – you’ve got to read that if you enjoyed this movie as much as we have. Through all of these excursions, you can tell that his tastes are not overly high-brow. (Remember his central thesis of Pop Culture Wars that all film and pop artifacts are religiously/philosophically laden and artfully serious, and his central thesis of Eyes Wide Open  that we can find signs of life and Godly insight from even pagan popular culture.) Cinematic Faith is hoping to enhance your viewing experiences and help you get more out of your entertainment dollar, not bore you with academic discourse or shame you for enjoying the movies you enjoy. Please know, this isn’t highbrow scholarly theory for snooty cineastes but a thoughtful tool for all of us, whether you like The Kings Speech or the X-Men series or Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War.

that we can find signs of life and Godly insight from even pagan popular culture.) Cinematic Faith is hoping to enhance your viewing experiences and help you get more out of your entertainment dollar, not bore you with academic discourse or shame you for enjoying the movies you enjoy. Please know, this isn’t highbrow scholarly theory for snooty cineastes but a thoughtful tool for all of us, whether you like The Kings Speech or the X-Men series or Marvel’s Captain America: Civil War.

READING WIDELY, VIEWING WIDELY

We loved, by the way, having literary scholar and teacher Karen Swallow Prior in our store last fall helping launch her marvelous book about virtue and literature On Reading Well: Finding the Good Life Through Great Books. She started her talk, as she does in the book, with the advice of old John Milton, who advised that we “read promiscuously.” The word didn’t have quite the immoral overtones in his 1600s that it does nowadays, but even then, the advice struck some as dangerous. Like Prior and her love of a wide range of reading, Romanowski is convinced that watching a lot of movies of different sorts is a good thing. Unlike literature, where reading widely is mostly admired, though, we tend to dismiss a thoughtful, spiritually aware engagement with our popular amusements.

Some think we shouldn’t watch many movies at all and others think it’s all fine, but don’t want to think about it much — who wants to think much, after all, let alone about God’s Kingdom or our moral formation, when we’re vegging out? Anyway, what’s the point of entertainment, after all?

TO ENTERTAIN OR ENLIGHTEN?

Romanowski addresses this a bit in a section called “To Entertain or Enlighten: That Is the Question.” You’ll have to read his answer, but, again: nothing is secular, so we are always being formed, one way or the other, and all moments in life can be avenues for construing meaning and growing as a person made in God’s likeness. Of course, we don’t have to have a steady diet of Schindler’s List and socially conscious documentaries. Remember, the first “Movie Musing” in this book is on Groundhog Day. And did I mention he likes Rocky?

So. What makes Cinematic Faith an important book, besides being a bit of a sequel to the important and popular Eyes Wide Open? We have literally a dozen recent books on faith and film that have come out in recent years. A genre that was once rather provocative and cutting edge has, it seems to me, become almost commonplace. And we don’t sell them as much as we used to.

Movies and digital entertainment (here in a new golden age of TV) are more popular than ever, taking up more of our time than ever before. (Indeed, we just got a new book by Dan Strange called Plugged In: Connecting Your Faith with Everything You Watch, Read, and Play that carries rave reviews by the likes of Bill Edgar and Tim Keller.)

Still, most Christian people, I’d guess, have never read anything about the relationship of faith and entertainment, have never studied any of the many books we stock on this. We really should, you know; like work or relationships or eating or voting, God wants us to take pleasure in this part of our discipleship, but in a fallen world, things can be distorted and depressing. We have to study up, learn more, deeper our curiosity so we can grow in to maturity in these aspects of life.

But what makes this book on film that urgent? Besides my personal loyalty to my old friend and the reputation of his well-respected work at Calvin College, why Cinematic Faith?

SEVERAL GOOD THINGS

I will name several good things that make this a very important contribution, not only for anyone serious about developing a uniquely and inherently Christian way of approaching film, but for ordinary folks who enjoy a good movie night from time to time.

I will name several good things that make this a very important contribution, not only for anyone serious about developing a uniquely and inherently Christian way of approaching film, but for ordinary folks who enjoy a good movie night from time to time.

First, as I’ve already suggested, the good professor is, in fact, a good professor. He is clear and teacherly about critical approaches — theories or ways of thinking about film. He explains how different schools of thought about film can enhance our own viewing. However, again, this isn’t abstract scholarship for insiders; he specifically says that a good approach should be practical and can “provide reliable insights, and sharpen our judgments.”

He is clear and informative and this will be helpful for you. As he puts it, “appreciating what makes movies artistically interesting and effective can make us better viewers and more creative storytellers.”

So: it is practical and helpful. Who couldn’t use a bit of help in knowing better what makes a film good? With this small investment of twenty bucks and time – okay, a bit longer than it takes to watch a movie – you’ll benefit by enjoying movies more. You can even eat popcorn as you turn the pages and nobody will shush your crunching.

Secondly, Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective on Movies and Meaning is valuable because of the author’s main assumptions; that are potent and wise. Again, the primary framework for Romanowski’s work, as we’ve noted, is that there is an insightful, Biblically-informed way to think about film as a cultural artifact, as art. I mentioned (significantly) that he  has been informed by the aesthetic theories of Calvin Seerveld (Rainbows for a Fallen World, Bearing Fresh Olive Leaves, Normative Aesthetics, Redemptive Art in Society) and more, including study and conversations with other philosophers of the arts such as philosophers such as Nicholas Wolterstorff and Lambert Zuidervaart as well as pop journalists like the great Steve Turner whose Imagine: A Vision for Christians in the Arts is a great book for anyone wanting to dip into an integrated Christian perspective on art and culture and whose Popcultured I already mentioned.) This means that Bill has worked very hard at a deep level to wonder what it means to take up theories and mindsets that inform dispositions and practices that are not only coherent and consistent from a Christian perspective but that are deeply integral. In this, he doesn’t get all preachy nor does he particularly wear his faith on his sleeve, but he is a reliable, faithful guide. Faith, in his scholarship, is not an afterthought nor is his sense of quality and value in a film based on cheap inspiration. I suppose we don’t have to say it here, but a novel or movie can tell a profoundly immoral story and be brilliantly made and wise; similarly an overtly Christian movie may have a lively religious message but be poorly made. Such films and books can even be dishonest about the way faith works in real life. Some of the most theologically sane movies have be made by deeply troubled filmmakers and some of our worst films are made by otherwise Godly people trying to use the art form for evangelistic purposes.

has been informed by the aesthetic theories of Calvin Seerveld (Rainbows for a Fallen World, Bearing Fresh Olive Leaves, Normative Aesthetics, Redemptive Art in Society) and more, including study and conversations with other philosophers of the arts such as philosophers such as Nicholas Wolterstorff and Lambert Zuidervaart as well as pop journalists like the great Steve Turner whose Imagine: A Vision for Christians in the Arts is a great book for anyone wanting to dip into an integrated Christian perspective on art and culture and whose Popcultured I already mentioned.) This means that Bill has worked very hard at a deep level to wonder what it means to take up theories and mindsets that inform dispositions and practices that are not only coherent and consistent from a Christian perspective but that are deeply integral. In this, he doesn’t get all preachy nor does he particularly wear his faith on his sleeve, but he is a reliable, faithful guide. Faith, in his scholarship, is not an afterthought nor is his sense of quality and value in a film based on cheap inspiration. I suppose we don’t have to say it here, but a novel or movie can tell a profoundly immoral story and be brilliantly made and wise; similarly an overtly Christian movie may have a lively religious message but be poorly made. Such films and books can even be dishonest about the way faith works in real life. Some of the most theologically sane movies have be made by deeply troubled filmmakers and some of our worst films are made by otherwise Godly people trying to use the art form for evangelistic purposes.

Art – visual art, multi-media art, literature or pop music – must not be propaganda. In fact, if a piece traffics in cheap clichés and/or pushy messages, it most likely isn’t very good art, which, by definition, must be allusive and imaginative. I’ve already counseled young Christian rock musicians to lay down their guitars and find a pulpit since they seem to think their calling is not to be an artist but to be a preacher. Preaching is a noble (and, at its best, also an artful) calling. But art – and in this case, movies – aren’t mere vehicles of didactic content. Art must, to cite Emily Dickinson, “tell it slant.” For a film, to work well, it must firstly be a good film; that is, good art, imaginatively telling a story.

We all know when a movie or TV show has been ham-fisted, and we feel like we’ve been manipulated or pummeled with a message. Marxists and progressives tend to do this a lot; evangelical Christians too often, too. Even if we tend to agree with the message, it hasn’t been a particularly edifying few hours of entertainment, has it? A good message is usually diluted by bad form or a propagandistic ethos. Conversely, an artistically nuanced and allusively subtle vision can be quietly powerful.

This insight – which is pretty basic, I suppose – has formed in Bill a professional passion (and, after watching a zillion films over a lifetime, a finely tuned craft) for understanding film not merely in its content, but it its style. And this is what makes Cinematic Faith a major contribution to and somewhat unique within contemporary Christian film studies.

It seems to me that most of our best Christian thinkers in film studies (many published by the same good publishing house as Cinematic Faith who over the last 15 years or so have served up a bounty of faith-based scholarship about culture and review of modern movies) have fallen somewhat for this inadequate perspective of how to evaluate film. That is, they spend a whole lot of time and effort to discern the worldviews of the filmmakers, or doing narrative criticism, exploring the story and the content and the message as if every movie has a moral. As Bill himself notes, this is natural—when telling a friend about a movie you’ve enjoyed or when considering with a date what film to see, we ask, “What’s it about?” Nobody first asks what stylistic vision the cinematographer has and to what effect their film-editor worked, as she spliced scenes with the soundtrack? But you know what? Maybe we should ask that sort of question about form and function, about aesthetics and craft. Because, after all, for a film to work it not only needs a good story but that story is told by artists with a point of view that is embodied in their craft, their form, their filmic skills.

“The critical approach presented in this book,” Romanowski writes, “is anchored in the film itself and its unique capabilities as an audiovisual medium.”

He continues:

Even professional film reviewers tend to rely on, “a heavy dose of plot synopsis,” New York Times critic Manohla Dargis concedes. They pay very little if any attention to the specifics of the medium, to how film makes meaning with images – with framing, editing, mise en scene, with the way an actor moves his body in front of the camera.”

He sets up our expectations for the book reminding us that:

This book does not propose to replace an emphasis on content with an emphasis on form but rather to treat film as both an aesthetic object and an experience – one that can be exciting, pleasurable, boring, disagreeable, or mind blowing.

This is really important stuff that I don’t see enough about in other such books.

ANOTHER GOOD THING: UNDERSTANDING INTERPRETATION

Further, Romanowski also writes about the interplay of production and reception; that is, our response to a movie is a dance with the filmmakers and her skills and perspective. Our “interpretive stance” comes into interaction with the worldviewish perspective of the filmmaker and the way in which they tell their story, which, I’d suppose, is itself embedded with all kinds of cultural baggage; the same story can be told from a variety of viewpoints from varying ideologies and perspectives, and different viewers will find meaning in different ways in this whole arty mess. No wonder the evaluations at Rotten Tomatoes sometimes vary so very vividly that conversations about favorite (or hated) films can be explosive.

Again, in Romanowski’s clear-headed prose, he reviews a major point:

The main concern is with the essential relationship between form (the patterns and techniques used to tell stories), content (the film’s subject), style (the filmmakers distinctive use of patterns and techniques), and perspective (the film or filmmaker’s point of view.)

And, oh my, how he later peels layer after layer of different sorts of interpretation – the surface meaning, and the directors deeper meaning and our own interpretive meanings. In this modern entertainment that blends art and outlook, through film-making style and vision, we somehow come out either enlightened in ways that are consistent with God’s Kingdom or we are recruited to other stories, conscripted (to use James K.A. Smith’s word) into false ways of being in the world. That Bill cites his colleague Jamie will be a touchstone to many who have read Smith’s extraordinary three volume cultural liturgies project (or the one-volume summary version, You Are What You Love.) Interpretation matters as we thereby can be more intentional about what movies shape us and in what way.

FOUR BIBLICAL PRINCIPLES

In the second chapter Romanowski offers in a no-nonsense manner four basic Biblical principles to serve as a guide for a productive engagement with cinema. In a few pages he packs extraordinary insight; for some, they might be new insight, or intuitions articulated in sensible ways.

The first of these ruminations is on the role of the arts (which “enriches by subtle disclosure rather than instant clarity.”) These few paragraphs are not to be missed.

Secondly, he offers a rare insight about the sense of the divine that Christian Scripture tells us everyone has, making, therefore, everyone somehow religious, and every film some sort of tribute to the filmmakers or directors “ultimate concerns.” No one is neutral or somehow not making meaning or framing life by some lights; all movies have this avoidable religious/ideological commitment to something.

Thirdly, Romo writes about how faith encompasses all of life and therefore “we should expect movies to deal with our full humanity.” Faith, in this approach, is the context for thinking about all films, not a topic that is only treated in some “religious” films. Our Christian convictions are like a lens through which we see all of life and can help us evaluate all films – that is, we aren’t just interested in overtly religious messages.

Lastly in this short section he explains what the Reformed tradition, at least, calls “common grace” – which carries the reminder that even if we always have a critical, aware, posture, we must never “lose sight of the fact that all people have the capacity for creativity and truthfulness.” Oh was a generous and important insight, especially in these days of deep polarization.

THE GOLDEN RULE FOR FILM CRITICISM

And then, Mr. Romanowski gives us The Golden Rule for Film Critique:

Together these four principles lay the groundwork for a two pronged approach that is both discerning and exploratory, characterized by encounter and dialogue. With this approach comes a certain attitude. This way of doing film analysis recognizes and values diverse perspectives, while also maintaining the importance of one’s own perspective in thinking critically about cinema.

The next few pages are, again, worth the price of the book, reminding us of the ups and downs of this process and posture. We must understand the value system of the film. Yet, we must be open to how other people (made in God’s image) experience and interpret life. Movies change us, and this isn’t altogether a bad thing.

Read this great little excerpt:

How can we critically engage film in imaginative ways that are mindful of and consistent with a faith perspective while also respecting the filmmakers vision and artistic expression? Or, to give it a slightly different twist, how are we to engage movies that are artistically praiseworthy and culturally significant but contain ideals and assumptions that might run against the grain of our own? Becoming impartial critics — fair and just in our judgments, and rising above our own prejudices – is easier said than done. Who would deny adhering to one’s own agenda when thinking about a film? The risk, of course, is that we might fail to refuse to give a filmmakers viewpoint a fair appraisal, or we might find it difficult to even appreciate an honest artistic effort.

Cinematic Faith advises us to engage a film on its own terms, “to resist the temptation to unfairly impose your own point of view, which adhering to your own vantage point as a place of reference to understand and think critically about the film. This calls for,” the author continues, “an approach that plays itself out along the border between conviction and humility.”

And with this, we’re really off to the movies!

MOVIEMAKING MAGIC

Chapter three is called “Moviemaking Magic” and here Romanowski unpacks“poetic portals and the power of perspective.” He starts with a splendid reminder of the Scorsese film Hugo, which is adapted from the great children’s book The Invention of Hugo Cabret – a spectacular YA story about a turn of the twentieth century French filmmaker. This is a great chapter reminding us about how stories really work, how filmmakers interpret reality and how we viewers then bring our own deeply felt value judgments to the experience of the film. He cites some other film scholars who talk about “imaginative orderings of experience” and a few other heady notions but this is really important and very interesting.

FORM AND CONTENT

He moves then into a chapter that might be considered a key one for Cinematic Faith, working more on what makes this book particularly special – the matters of style and craft and film-making (and not only content or message.) This part is called “Creating an Illusion of Reality: Film Form and Content.” Here we get into the weeds a bit, but it’s really fascinating. His first discussion as he teaches us about this is of 1995’s witty coming-of-age film set in Beverly Hills high school, Clueless. (Did you know it is loosely based on Jane Austen’s Emma and critics said it had a “razor sharp script”?) Professor R names a dozen other movies in as many pages exploring this dual emphasis of style and content, of medium and message, if you will. I am no expert on this, so I learned a lot and I am convinced it is important.

I recall decades ago Francis Schaeffer saying that, just for instance, a movie about nihilism, say, couldn’t be well told if it was lighthearted; form somehow is related to function, right? Bill used to give talks about this stuff when we worked in campus ministry and I recall him speaking about how a beautiful/joyous concept can’t be captured in ugly forms; different styles of songs are suited for different settings – from a wedding night, say, or to a tragic funeral. One can’t express the heart-wrenching sadness of a tragic death in a peppy little disco tune, right? Good cheer and gravitas have their places, and aesthetic form carries much of the weight of these human emotions, in music and TV and dance and other art forms. And so it is in film, perhaps even with style trumping content, sometimes. Ideally, Romanowski says, “form and content are essential and mutually dependent aspects of a film — two sides of the same coin, so to speak.”

So, naturally, we should know a bit about cinematic tools such as narrative, cinematography, production design, sound, acting, and editing. Under his helpful tutelage we learn not just what happens in a film, but the way it happens.

And – bam! pow! — he sure gives us lots of examples of just what he’s talking about. From the special effects team in Harry Potter and the Half-Blood Prince showing the Death Eaters flying to some sexy opening shots in Top Gun that places gender in the center of the story, to great, if brief, comments about the much-awarded cinematography of Emmanuel Lubezki (who, Romanowski reminds us, won an Oscar three years in a row for Gravity (2013), Birdman(2014), and in 2015 for The Revenant) this section is chock full of quick examples and fun illustrations and even movie stills.

On and on we go through this book, covering all sorts of things that are fun to learn, helpful to realize, wise reminders and fresh formulations. This book could serve as a good read for a film-going group or a college class or a book club. Again, you’ll enjoy movies more and be more faithful (Christian) viewers if you learn a bit. It shows how filmmakers connect the dots by exploring further the relationship between “style and meaning.”

Romanowski opens this good chapter by highlighting a debate in Commonweal about a Catholic film critic who appreciated a fundamental moral center to movies like Pulp Fiction. In answering the popular critics who thought he went too far in affirming the goodness of a violent film, reviewer Richard Alleva replies, “I will persist in recognizing the morality in art by exploring the art in art.” What an interesting line; Romanowski jumps from there into the insights we can get when we have enough awareness of these things to relate a film’s form and content and style – especially when the film itself is artful enough to harmonize these features.

EVALUATION & CRITICISM

This notion that we can be redemptively Christian in our interpretations (by being savvy about film style and enjoying a movie as an artfully constructed story) has long been part of Bill’s strong repertoire. But his scholarship over the years (in academic film studies journals and papers presented at mainstream academic conferences) has been on the “American style” redemption that movies often present us (and how those often violent myths are a different sort of redemption than that offered by Christ and the Christian gospel.)

Others have written about this as well, but I appreciate Romanowski’s take – in one chapter he looks at Titanic “a consummate Hollywood blockbuster film” (which explores melodrama) and in another chapter (“The Yellow Brick Road to Self Realization”) he looks at classical Hollywood cinema and the tropes and values inherent in this sort of storytelling. You’ll be surprised to see how he weaves together comments about Oz and Casablanca, The Big Short and (get this) Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing.

Even those not interested in action adventure movies will appreciate the chapter called “A Man’s Gotta Do What a Man’s Gotta Do” in which he offers his seriously Christian worldview and faith-based guidelines to explore a whole host of important issues in this popular genre. From stuff about gender and violence and heroism he brings new insights to films that he sees connect to this particularly American mythology. He has a “Movie Musing” here on 2014’s Noah – “a big-budget Hollywood epic drama conceived as a variation of sorts on the American mono-myth.” That was a surprising (and compelling) take on what I supposed was just a nod to the religious market by doing a Bible story.

And then he goes from he assessment of the conventional American myths to a full-on study of gender in mainstream Hollywood. As a guy with long-standing sensitivity to the critiques of machismo, a critique he has himself been making for decades, this chapter, called “Stop Taking My Hand!” (which is a line from Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens), looks at “gendered cultural patterns” about the ideal man or woman. Do these images reflect our values and assumptions or shape them? What might the recent interest in strong female characters bode for film and storytelling? With explorations of Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games) to Hilary Swank’s awarded winning Maggie Fitzgerald being trained in boxing by Clint Eastwood’s character in Million Dollar Baby, Romanowski brings fascinating and I think wise insight to questions of gender and sexuality and relationships.

And then he goes from he assessment of the conventional American myths to a full-on study of gender in mainstream Hollywood. As a guy with long-standing sensitivity to the critiques of machismo, a critique he has himself been making for decades, this chapter, called “Stop Taking My Hand!” (which is a line from Rey in Star Wars: The Force Awakens), looks at “gendered cultural patterns” about the ideal man or woman. Do these images reflect our values and assumptions or shape them? What might the recent interest in strong female characters bode for film and storytelling? With explorations of Katniss Everdeen (The Hunger Games) to Hilary Swank’s awarded winning Maggie Fitzgerald being trained in boxing by Clint Eastwood’s character in Million Dollar Baby, Romanowski brings fascinating and I think wise insight to questions of gender and sexuality and relationships.

He does not particularly address films about LGBTQ characters, by the way, but his framework about being critical of American mythologies of traditional gender assumptions (he reads the Bible as offering a trajectory towards egalitarian justice) could provide tools for a positive Christian engagement with all sorts of films around those themes, as well. There are a host of other topics and issues in contemporary culture that his film studies approach will prove generative for us as we seek to “find God in popular culture.” His gift to us, besides lots of musings on lots of specific movies, is a deeper framework and wise orientation to film interpretation, appreciation, and evaluation.

There’s plenty more in Cinematic Faith, from a strong reminder that the routine vision of American individualistic self salvation in many films is a far cry from the core tenant of being save by God’s grace, to a unique study of The Blind Side, to a wonderful epilogue that draws on Shrek. For those with eyes to see, all films can and do express meaning and “communicate life perspectives.” They can help us see and they can help us care.

Can knowing a bit about how they are made and how they work on us and how to critically engage them help us discern those that “resonate with a biblical outlook and so deepen our awareness of the ways that humans bear God’s image and flourish through acts of love, forgiveness, and generosity?” This book insists yes. We can truly enjoy movies and be challenged and grow through their artful style – especially if we know something about it all.

Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective on Movies and Meaning stands out as a large gift to anyone that who enjoys movies and film and certainly anyone who is attempt to be intentionally faithful in “finding God in popular culture.”

FILM AND THEOLOGY?

A final comment about why on some occasions, it seems, church folk (almost all of whom surely watch TV and movies) seem surprised when we have books displayed at their events like Cinematic Faith: A Christian Perspective…

I think it is because some religionists and many common people in the pew seem to think that all God cares about is church and maybe the study of theology.

And, you see, technically speaking, Romanowski’s book is not about theology (proper) or even “in dialogue with” theology or church leaders. It is deeply Christian, particularly standing in this reformational tradition, that doesn’t favor theology over other areas of study. He teaches at a Christian college, but he isn’t a theologian. He attends his church, but isn’t primarily a churchman. He’s a (Christian) film professor and a movie-watcher. He wants to offer us a faith-based, Christian perspective on film making and film viewing, for film makers and film viewers whether they do theology or church work, or not.

He wants to equip us to live our ordinary faith before God with intentionality in ways that are distinctive to this side of life – leisure, entertainment, the arts. That is, he isn’t pretending to do theology and he isn’t particularly asking theologians to chime in. And I think that is as it should be.

And yet, that is an approach that is so popular (also in the sciences, it seems) that it’s nearly a school of thought, with many books that invite us to listen in on a conversation between film buffs and theologians. Can you see how that is a bit different that what Romanowski’s project is? He doesn’t privilege theologians and the book isn’t about theology: it’s about movies and entertainment and those moments of allusion and imagination and nuance and artfulness we experience went we enter into a creatively told story. It is for artists and those of us eager to open up our aesthetic side of life, even in our entertainments, our play, our going to the movies. The recent movement of conversations between film-makers and theologians is fascinating, and many books with that approach have chapters that are nothing short of brilliant. But most are doing this rather arcane project – uniting Christian movie lovers with Christian theological scholars. Romanowski, in Cinematic Faith, as he has done throughout his career, has engaged mainstream film studies and taught us ordinary folks how it all works. Informed by good scholarship – from an integral Christian social imaginary and Biblically-grounded life perspective, to be sure – he helps us all be more attentive and faithful, even in our entertainments. In this regard, Cinematic Faith is for us all.

ONE MORE GREAT RECENT BOOK ABOUT FILM & FAITH

Deep Focus: Film and Theology in Dialogue Robert Johnston, Craig Detweiler and Kutter Callaway (Baker Academic) $26.99 As I’ve hinted above, I’m not inclined to be particularly interested in seeing what theologians, as such, have to say about film studies. A book about movies that has churchy stained glass on the cover strikes me as awkward. This sort of approach just seems somehow off to me, as if we have to somehow sanctify the ordinary act of watching movies not by thinking Christianly about movies (as Romanowski would argue) but that we need these professional thinkers about theology to make it so.

Deep Focus: Film and Theology in Dialogue Robert Johnston, Craig Detweiler and Kutter Callaway (Baker Academic) $26.99 As I’ve hinted above, I’m not inclined to be particularly interested in seeing what theologians, as such, have to say about film studies. A book about movies that has churchy stained glass on the cover strikes me as awkward. This sort of approach just seems somehow off to me, as if we have to somehow sanctify the ordinary act of watching movies not by thinking Christianly about movies (as Romanowski would argue) but that we need these professional thinkers about theology to make it so.

For what it is worth, I’d similarly say that that businesspeople need a Christian view of economics, not a “theology” of business and that, likewise, Christians in the sciences, say, need a faithful view of their research in God’s good world, a Christian approach to to the philosophy of science, less a “dialogue” with “theologians.” That these important authors of Deep Focus: Film and Theology in Dialogue (who have also done several other significant books that emerged out of their Reel Spirituality Institute at Fuller Theological Seminary) are all fine gents who served at a seminary probably makes this approach a natural in their world, I suppose. And, in this case, it sure is interesting, I’ll give that. Wow.

I just seem to discern – and I admit this may be a little unfair – a lurking dualism, rooted in the “sacred vs. secular” dichotomy that actually evolved in the church from pagan Plato, in this talk about a “secular” profession (business, science, art) needing to be “in conversation with” theology. Theology is an interesting, important, specialty, but why somebody with that specialty is privileged to be a necessary conversation partner conjures up for me an image of some some sacred/spiritual icing on the secular cake where faith is an ad-on, perfunctory. I’m sure they wouldn’t put it this way, but it nearly sounds as if secular movies can’t be discussed Christianly with Christianly-conceived aesthetic theories and coherent film studies approaches by movie makers and movie goers unless the religious guys from the theology department bless it all. It’s a caricature, I know, and a bit picky on my part, but it’s what this “theology of..” or “theology and…” lingo too often connotes.

Having said that, I was gobsmacked by how much I loved this Deep Focus: Film and Theology in Dialogue book.

Yes, I loved this book and found it hard to put down.

I can’t explain it all in detail now, but allow me to say I think this is the best volume yet to come out of this Reel Spirituality movement, and there have been some good ones (we we stock them all.) The authors really know their stuff, tell some personal stories about moments they’ve had at the Cineplex and I found it very enjoyable, quite stimulating, and even provocative. I’d highly recommend it as a follow-up or companion to Romanowski’s must-read Cinematic Faith.

Listen to Stefanie Knauss of Villanova University as she raves about Deep Focus:

Offering great movie choices, insightful analysis, wonderful prose, rich knowledge about film and theology – this book has it all. It’s a great read for all who are interested in the field of film and theology and offers the necessary tools to engage in this conversation in a knowledgeable, substantial way.

The publication of this new book this season – called “engaging, fluent and timely” – is curious. Romanowski, in his neat book, implies (but does not rail out loud) that too many Christian film studies volumes overestimate the role of content and underestimate the role of style, the art of the filmmaking craft. As we’ve seen above, Professor Romanowski suggests this isn’t adequate, that we must see how the aesthetics of the art of the filmmaking and directing and acting crafts influences how we then engage the movies themselves, as films. He suggests, as I’ve implied, that not enough of the Christian books on film do this that much.